71 Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Treat all patients to a disease activity target—remission or low disease activity.

For most patients, methotrexate will be the cornerstone of DMARD therapy.

Many patients will require combinations of DMARDs with or without biologics to achieve the target.

Many effective biologic DMARDs are available—all are more effective with methotrexate.

NSAIDS may provide useful symptom control but are rarely indicated without DMARDs.

Aggressively address the ubiquitous comorbidities of RA, especially cardiovascular disease.

The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has evolved dramatically over the past 30 years, perhaps more so than any of the rheumatic diseases. The majority of patients newly diagnosed with RA in 2013 can expect to have their disease in remission if treated early by a rheumatologist. This remarkable fact has come about because of a tremendous expansion of the number of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) available (Table 71-1), the realization that these drugs can and should be used in combinations,1–3 and the acceptance that all patients should be treated to a target or goal of remission or low disease activity.1–4 To put the current situation into perspective and to celebrate how far we have come, a look back on the most immediate history of RA treatment as chronicled in the 30 years of the Textbook of Rheumatology (TOR) seems appropriate.

Table 71-1 Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs*

| Conventional | Biologics |

|---|---|

| Methotrexate | Etanercept (Enbrel) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Infliximab (Remicade) |

| Sulfasalazine | Anakinra (Kineret) |

| Leflunomide | Adalimumab (Humira) |

| Gold (intramuscular and oral) | Abatacept (Orencia) |

| Azathioprine | Rituximab (Rituxan) |

| Minocycline | Certolizumab (Cimzia) |

| Cyclosporine | Golimumab (Simponi) |

| Penicillamine | Tocilizumab (Actemra) |

| Glucocorticoids |

* Currently available drugs that have the ability to slow or halt progression of rheumatoid arthritis including radiographic progression.

This chapter attempts to discuss the broad principles of treatment, the goals of RA therapy, the timing of different therapies, and the strategies of employing the plethora of options now available to achieve the best control of each patient. Most of the drugs are not covered in detail here; please refer to other excellent chapters for specifics on the NSAIDs (Chapter 59), glucocorticoids (Chapter 60), traditional DMARDs (Chapter 61), immunoregulatory drugs (Chapter 62), and anticytokine therapies or biologics (Chapter 63).

Goal of Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment

It is remarkable that rheumatologists now have more than 19 approved conventional or biologic DMARDs to choose from. However, despite all these terrific DMARD options, the most important paradigm shift for the treatment of RA has been the realization that patients should be treated early and to a target of low disease activity or remission.1–4 For those outside the rheumatologic community, this seems like stating the obvious—if you have hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes, patients are of course treated to get the blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein, or HbA1c, respectively, down to a defined and easily measured goal. The problem in RA has been having valid reproducible measures of disease activity and remission and then routinely measuring and following those in a clinic. Unfortunately, in RA, there is no single examination finding or laboratory test that satisfactorily measures disease activity.

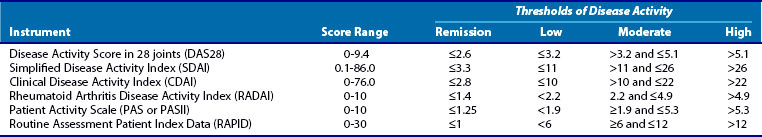

Many measures have been proposed,5–10 and all are composite measures that include information derived from some combination of joint examinations, patient and physician assessment of disease activity, patient function, and laboratory measures of inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] or C-reactive protein [CRP]). Recently, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has endorsed a list of disease activity measures that have been shown to correlate with outcomes. Table 71-2 is a partial list of some of the better known of these measures. Each of these measures have strengths and weaknesses11; some rely on only data from the patient, some require complete joint counts by clinicians, and some require laboratory tests to measure inflammation. The busy clinician rarely has time to document more than 60 tender and swollen joints or wait for laboratory test results to make decisions on patients during their visit. Therefore measures that simplify this process as much as possible are being embraced including those that limit the joints counted to 28 (Disease Activity Score 28 [DAS28]), do not require laboratory tests (Clinical Disease Activity Index [CDAI]), or are entirely dependent on patient data Routine Assessment Patient Index ([RAPID]). There is high correlation among these measures, so currently in the clinic it is very important that disease activity is measured and less important which measure is used.

Because none of our therapies cure RA, it seems obvious that the next best goal should be remission. The concept of remission as a goal for RA patients is problematic, however. First, a remission definition that is both relevant and practical has been elusive. To be relevant, remission should be highly predictive of the absence of disease progression over time. To be practical, for clinicians, a remission definition should be easy to apply in real time to patients seen in a clinic as discussed earlier with regard to measures of disease activity. Recently, a new definition of remission for use in clinical trials has been developed by ACR and the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) (Table 71-3).12 This definition has been rigorously tested against short-term radiologic outcomes in 1- to 2-year randomized controlled trials (RCTs) follow-up. This definition standardizes remission and is therefore a huge step forward for reporting and comparing results across clinical trials.

Table 71-3 ACR/EULAR Definitions of Remission in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials

| Boolean-Based Definition |

| Index-Based Definition |

| At any time point, patient must have a Simplified Disease Activity Index score of ≤3.3 |

ACR/EULAR, American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism.

* Include 28 joints plus feet and ankles.

From Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al: American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials, Arthritis Rheum 63:573–586, 2011.

However, this definition was designed for clinical trials, not clinical care,13 where the need to have results of CRPs in real time becomes a problem. Versions of this that do not require laboratory values have been suggested but not fully accepted (e.g., CDAI, Patient Activity Scale). Perhaps more problematic, many believe that remission defined by clinical data alone will always underestimate the amount of low-level disease activity that could be found if synovial biopsies or advanced imaging techniques such as ultrasound (US) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were employed (see Chapter 58). Significant data exists that many and perhaps most RA patients who meet definitions of “remission” have active disease if assessed by US or MRI.14–16 Indeed, the newly accepted ACR/EULAR definition allows for a swollen joint, which many would argue is not really remission. Another major problem with “remission” is that from currently available data it is not at all clear that remission, regardless of how it is defined, should be the treatment goal for all RA patients. Many patients do well despite low levels of disease activity. This situation may be analogous to the recent studies that show pushing HbA1c levels below 6.5, which seemed appropriate for diabetic control, was associated with increased cardiovascular mortality mainly due to hypoglycemia in patients with prior cardiovascular histories.17

• When do the risks and considerable expense of some of our RA therapies outweigh the benefits of escalating therapy further?

• Which patient who has improved dramatically but still has two tender or swollen joints needs a third biologic?

• With regard to the previously cited diabetic patients with cardiovascular disease, which RA patients are most at risk if we push too hard for remission?

• Finally, with current therapies, the vast majority of remissions in RA require ongoing treatment with DMARDs, so the concept of a true remission, meaning one where no therapy is required, remains beyond our current reach for the majority of patients.

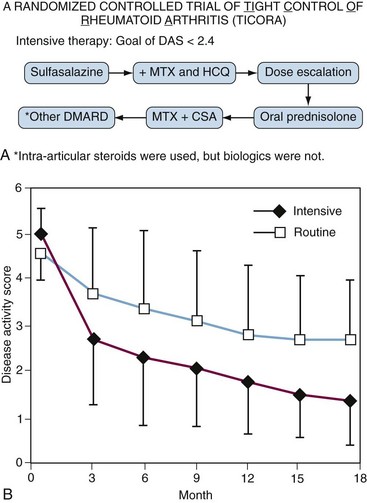

Despite the problems defining remission or low-disease activity, it is clear that patients do better if clinicians have a goal. The Tight Intensive Control of RA (TICORA) study18 was the first to convincingly demonstrate this in a randomized fashion. TICORA was a Scottish study in which patients with less than 5 years of disease were randomized to receive either routine care or to receive intensive care. Both groups were treated with an algorithm of conventional DMARDs (Figure 71-1A). The routine care group had regular follow-up and monitoring, while the intensive group was seen monthly and had proscribed escalation of therapy (protocolized) if they had not achieved the goal of low disease activity (defined in this study as DAS ≤ 2.4). Both groups improved significantly, but the group that was treated to a target (intensive group) did significantly better with mean DAS scores (=1.6) in the remission range at 18 months (Figure 71-1B). In the intensive group, 71% achieved an American Colllege of Rheumatology 70% improvement criteria response (ACR70) compared with 18% in the routine care group (P < .0001). Further, this clinical improvement translated to significantly less radiographic progression of erosions compared with the routine group (0.5 vs. 3.0; P = .002). Importantly, this improved disease control was not associated with an increase in treatment-associated adverse events. Finally, despite more frequent visits, intensive therapy resulted in cost savings even in the short term. These results were particularly remarkable considering they were obtained using conventional DMARDs alone (see Figure 71-1A) without the use of biologics. Findings from other studies have corroborated these findings.19–21 Further, a meta-analysis of tight control22 suggested that tight control strategies work best if protocolized, as was done in TICORA.

Although the TICORA investigators selected low disease activity as the target, the target could have been remission as discussed earlier. Most of the previously endorsed measures of disease activity have defined levels that signify “remission” (see Table 71-2). Predictably, the harder we push for remission with increasing numbers and doses of DMARDs, both conventional and biologic, the more toxicity and the expense (Table 71-4) of our treatments become a concern. Both the ACR and EULAR guidelines, as well as recent reviews,1–4 currently state that low disease activity or remission is the goal, and they leave the decision on which one is most appropriate for each unique patient’s situation to the clinician. Therefore until further data elucidate this question, clinicians will need to continue to practice the art and science of medicine when selecting the most appropriate target for each patient.

Table 71-4 Average Medication Expense*

| Medication | Dosage | Monthly Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate | 20 mg/wk | $26 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 200 mg twice daily | $35 |

| Sulfasalazine | 1 g twice daily | $30 |

| Prednisone | 10 mg/day | $10 |

| Triple therapy | Above doses | $91 |

| Etanercept | 50 mg/wk | $1974 |

| Adalimumab | 40 mg every other wk | $1915 |

| Infliximab | 300 mg/4 wk | $2264† |

| Rituximab | 1500 mg every 6 mo | $1597‡ |

| Abatacept | 750 mg monthly | $1690‡ |

| Tocilizumab | 400 mg monthly | $1555‡ |

* U.S. $/month cost to consumer from large national chain pharmacy (Walgreens) in 2011.

† Based on average wholesale price as listed by Redbook and does not include infusion costs.

Classes of Drugs

DMARDs: Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine, Hydroxychloroquine, and Leflunomide

The definition of a DMARD is one that has the ability to change (for the better) the course of RA. The most rigorous application of this definition requires RCTs that show not only the ability to change the clinical course of the disease but also the ability to decrease or halt the radiographic progression. By this definition, all of the 10 conventional DMARDs and the 9 biologic DMARDs listed in Table 71-1 qualify with the possible exception of minocycline and HCQ, where only weak evidence exists for radiographic benefits. With the DMARDs listed in Table 71-1 and using these drugs individually or in combinations of two, three, or four as is often done, there are 2569 possible combinations for each individual patient, assuming that biologics are not used in combinations with each other. Obviously, this huge number of choices is both good and bad news for the clinician; it is great to have all the options but impossible to keep them all straight. Therefore to employ these effectively, the clinician must have goals, strategies, and an up-to-date knowledge of the drugs and their interactions and toxicities.

The most widely used conventional DMARDs—MTX, SSZ, HCQ, and leflunomide (LEF)—are discussed in detail in Chapter 61. Together, these four DMARDs along with glucocorticoids (see Chapter 60) currently account for the vast majority of conventional DMARD use. Although less commonly used, gold (both intramuscular [IM] and oral), azathioprine, cyclosporine, and the tetracyclines (minocycline and doxycycline), which are not covered elsewhere in the book, are therefore discussed as follows. Penicillamine is of historical interest23 but is rarely used and is not discussed in this chapter.

Biologic DMARDs

The biologic DMARDs are discussed in detail in Chapter 63. Within this class of agents we now have the ability to inhibit multiple inflammatory cytokines including TNF (with three monoclonal antibodies (infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab); the TNF receptor protein (ETAN); and the pegylated Fab fragment certolizumab, interleukin-1 (IL-1) with the IL-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra), IL-6 (monoclonal antibody to the IL-6 receptor tocilizumab) or to kill or inhibit cell lines important in inflammation including B cells (rituximab) and T cells (abatacept). It is an understatement to say biologics have changed the landscape of RA therapy forever both in terms of therapeutic expectations and understanding of RA pathogenesis. Because of their often quick onset of action, particularly with the TNF inhibitors, and their ability to retard radiographic progress, they are increasingly used earlier and more often in RA. The challenge for clinicians is to appropriately integrate conventional and biologic therapies and to use biologics when necessary but to make sure the much less expensive conventional therapies have been maximized.

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids, discussed in detail in Chapter 60, have a long and storied history in the treatment of RA. RA was selected as the first disease to be treated with “compound E” at the Mayo Clinic in 1948.24 Responses were both rapid and dramatic; an analysis of the first 14 patients treated revealed that 100% improved their ESRs by more than 50% within 1 to 3 months, with 80% improving ESRs by at least 70% (an ESR70—a convenient ACR70). Several landmark studies have proven not only clinical efficacy25–30 but also the significant radiographic efficacy of glucocorticoids.28,30 The recent COBRA trial29,30 and the COBRA arm of the BeSt study (discussed later19,20) again demonstrated the significant clinical and radiographic benefit that glucocorticoids can provide. Despite the rapid onset and all the other positive benefits of glucocorticoids in RA, their toxicities are also legend. Currently glucocorticoids are most often and most appropriately used along with DMARDs as part of initial “induction” therapy to get RA patients under control rapidly and then aggressively tapered as the slower-acting DMARDs start to kick in. Historically, the belief has been that once an RA patient was on glucocorticoids, he or she would never get off. This is clearly not true with the effective DMARDs now available—successful tapering is the rule.19,20,31 If a patient cannot be successfully tapered off or at least tapered to an “acceptable” low dose, it is a strong indication that the current DMARD program is not working. Long-term use of doses equivalent to prednisone of greater than 7.5 to 10 mg per day is a clear indication that DMARD therapy needs to be escalated. Importantly, glucocorticoids should almost never be used in RA without DMARDs.

Other Conventional DMARDs

Gold Salts

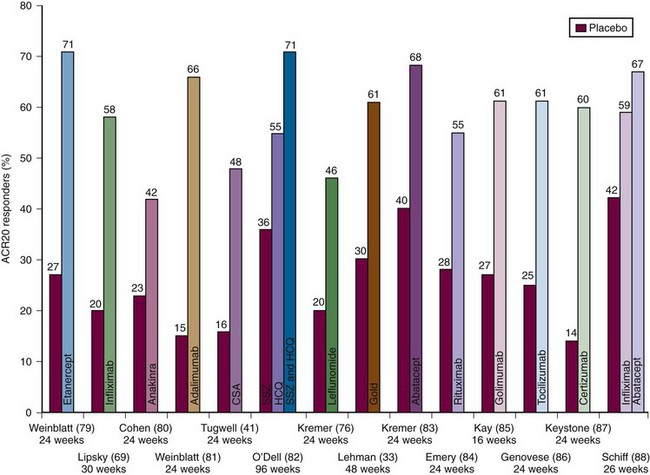

Gold injections have been used in the treatment of RA for close to a century—initially intramuscularly and, more recently, orally. With the advent of newer agents, gold is rarely used in most parts of the world. IM gold is a difficult and cumbersome therapy. It is initiated with weekly IM injections, usually starting with 10 mg the first week, 25 mg the second week, and then 50 mg thereafter, until a response is seen, generally between 3 and 6 months. Once the desired efficacy is seen, the IM injections can eventually be monthly. Frequent monitoring with complete blood counts (CBCs) and urine for protein is necessary. Significant toxicities can occur and include skin rashes, bone marrow depression, and nephrotic syndrome. As problematic as gold treatment is, there is a wealth of evidence that IM gold therapy is beneficial for RA including retarding radiographic progression.32 Some patients, perhaps 10% to 20% of those started on IM gold, will have essentially complete long-term remissions if maintained on injections every 2 to 4 weeks. Of recent interest was a 48-week RCT in patients with active disease despite MTX; the addition of IM gold to MTX resulted in 61% of patients achieving an ACR20 compared with 30% for the MTX + placebo group (Figure 71-2).33 Despite the known benefits, there is also ample evidence that the two IM compounds, gold sodium thiomalate and gold sodium thioglucose, are being used less by rheumatologists because of the need for meticulous monitoring for serious toxicity and the inconvenience of administration and monitoring.

Auranofin, the gold oral preparation, has been available for more than 20 years but is rarely used. Auranofin has different and less severe toxicity than the IM gold and reportedly less efficacy. Cytopenia and proteinuria are rare, but an enterocolitis with diarrhea leads to intolerance in many. Auranofin is an effective DMARD,34 but RCT data show that it is less effective than MTX, IM gold, penicillamine, or SSZ.35

Until or unless factors can be found that reliably predict who will get the almost magical clinical response that can be seen with gold, this cumbersome and often difficult-to-manage therapy will continue to disappear. To this end, HLA-DR3 is found in more patients who develop either thrombocytopenia or nephropathy while taking gold injections.36 These data must be balanced against the evidence that human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR3 may be associated with a better response to gold therapy, which corroborates a long-time belief shared by many clinicians that those patients who get rashes on gold are often destined to have excellent clinical responses.

Immunosuppressive Agents

Azathioprine

Azathioprine (AZA), 50 to 200 mg/day, has been used to treat RA for almost 50 years. Because it has been generic for many years, little recent research has been done. Although clearly not a first-line DMARD in contemporary RA treatment, AZA is most commonly used as a substitute for MTX when there are contraindications or intolerance to MTX. This most commonly arises in patients with the so-called “MTX flu,” but other situations including pregnancy, liver disease, and renal disease may be indications for AZA in RA. Azathioprine is usually used in combination with other conventional or biologic DMARDs. McCarty and co-workers, who was one of the pioneers of combination therapy in RA, has reported on the combination of MTX, AZA, and HCQ in 69 patients treated in an open-label fashion.37 With this combination, 45% of patients reached remission by the old ACR criteria38 and this combination was well-tolerated.

Neutropenia is the most common complication of AZA treatment. Neutropenia can be predicted with a genetic test for polymorphisms of the enzyme thiopurine methyltransferase (TMPT). Patients who are homozygous for the mutant polymorphism that is nonfunctional (1 in 300 or 0.3% of patients) are sensitive to bone marrow and other toxicities of AZA. Patients who are heterozygotes (perhaps 10% of the population) may have milder neutropenia.39 Unfortunately, this test is expensive. In some centers it may cost up to $1000 and is not always reimbursed. Some clinicians elect to start with low doses of 50 mg/day and check CBCs at 2 weeks and then increase the dose as needed if the white blood cell (WBC) count is normal. It has been speculated that the subset of patients with the nonfunctional polymorphisms could be the patients who, when AZA was added to a stable MTX regimen, developed an acute febrile toxic reaction characterized by fever, leukocytosis, and a cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis.40

Cyclosporine

In the 1990s, cyclosporine (CSA) gained a foothold in the treatment of RA.41 Cyclosporine, mostly used in transplantation to prevent allograft rejection, inhibits the activation of CD4+ helper-inducer T lymphocytes by blocking IL-2 and other T helper type 1 cytokine production42 and by inhibiting CD40 ligand expression in T lymphocytes.43 The latter effect prevents T cells from delivering CD40 ligand-dependent signals to B cells. Interest in CSA peaked in the mid-1990s when Tugwell and colleagues44 showed that the addition of CSA (2.5 to 5 mg/kg/day) to a stable dose of MTX provided substantial additive benefit over MTX alone. In the CSA + MTX group, ACR20 responses were achieved by 48% compared with 16% for placebo (see Figure 71-2). Additionally, this therapy seemed to slow radiographic progression of erosions.45 In this trial, the dose of CSA was decreased if the patient’s creatinine level increased to more than 30% of initial values. Unfortunately, follow-up reports on this regimen have revealed that only 22% of patients continued on this combination at 18 months with the most common reasons for discontinuation being hypertension or increasing creatinines.45

Minocycline and Doxycycline

Tetracycline and derivatives have a long and somewhat checkered history with regard to the treatment of RA and other arthritidies.46,47 The mechanism of action of tetracyclines in RA is poorly understood. Tetracyclines are, of course, antibiotics, but additionally they inhibit metalloproteinases, modulate immune responses, and have anti-inflammatory effects. No evidence indicates that tetracyclines treat the “infection that causes RA” as was touted by some of the original supporters.47 However, it is entirely possible that inhibition of nonspecific infections that upregulate the immune response (IL-1, TNF, IL-6) such as periodontitis, bronchitis, and gastritis, to name a few, may be helpful in controlling disease in RA patients. Tetracyclines also have the ability to inhibit biosynthesis and activity of matrix metalloproteinases that have a principal role in degrading articular cartilage in RA. This has been effective in animal models of osteoarthritis (OA) treatment. The presumed mechanism is through chelation of calcium and zinc molecules, which subsequently leads to altered molecular conformations of proenzymes sufficiently to inactive them.48,49 Minocycline has mild but definite inhibitory effects on synovial T cell proliferation and cytokine production and has been shown to upregulate IL-10 production. Further evidence of its ability to modulate the immune system is the fact that it is known to induce anti-DNA-antibody positive lupus in some patients, especially when used to treat acne.

Given in a dose of 100 mg twice daily, moderate statistically significant improvement in clinical parameters of disease activity was found in patients with established RA treated with minocycline compared with placebo.50,51 Findings in the treatment of early RA have been more impressive. A study of 46 patients with early rheumatoid factor (RF)-positive RA who had not received previous treatment reported 65% of patients meeting 50% improvement in tender and swollen joints, duration of morning stiffness, and ESR (Paulus criteria), whereas only 13% of the placebo recipients improved similarly over a 6-month period.52 In 2001 the results of a 2-year trial comparing minocycline with HCQ were published.31 In this small study of patients with early RF-positive RA, the patients treated with minocycline were more likely to achieve an ACR50 (the primary end point) than the patients treated with HCQ (60% vs. 33%) and were more successful in tapering glucocorticoids. This study reconfirms the potential utility of minocycline, particularly in early RF-positive patients.

Although less studied, there is evidence supporting the use of doxycycline in the treatment of RA. In a trial of patients with early RA, doxycycline plus MTX was compared with the use of MTX alone. Investigators studied low-dose doxycycline (20 mg twice a day) and high-dose doxycycline (100 mg twice a day) in combination with MTX and found that both approaches were superior to MTX alone.53 Despite the positive results of this study, replication is necessary.

Potential side effects of tetracyclines include light-headedness, vertigo, rare liver toxicity, drug-induced lupus, and, with longer-term use, cutaneous hyperpigmentation.54 Elderly patients appear to be at an increased risk of vertigo. Patients on minocycline have developed lupus-like syndromes, complete with autoantibodies including anti-DNA and occasionally perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antigen.55 Drug-induced lupus has not been reported to develop with doxycycline or with the use of minocycline in patients with RA. The hyperpigmentation can be impressive and may limit treatment in some.54 Hyperpigmentation resolves with discontinuation of minocycline and occurs much less commonly if at all with doxycycline.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs including salicylates, covered in detail in Chapter 59, have been a ubiquitous part of RA treatment for more than a century. Over the past several decades as toxicities,56–61 particularly gastrointestinal56–58 and cardiovascular, have become apparent58,59 and as DMARDs have become better, the use of NSAIDs has fortunately declined. The somewhat surprising cardiovascular toxicities, now known to be strongly associated with not only the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) specific NSAIDs but essentially all NSAIDs, have been particularly concerning with regard to the RA patient populations in which the main excess mortality is largely due to accelerated cardiovascular disease. Like glucocorticoids, NSAIDs should rarely be used without DMARDs. Also like glucocorticoids, the goal should be to taper off as soon as possible to avoid gastrointestinal and cardiovascular toxicities.

Treatment Approaches and Strategies

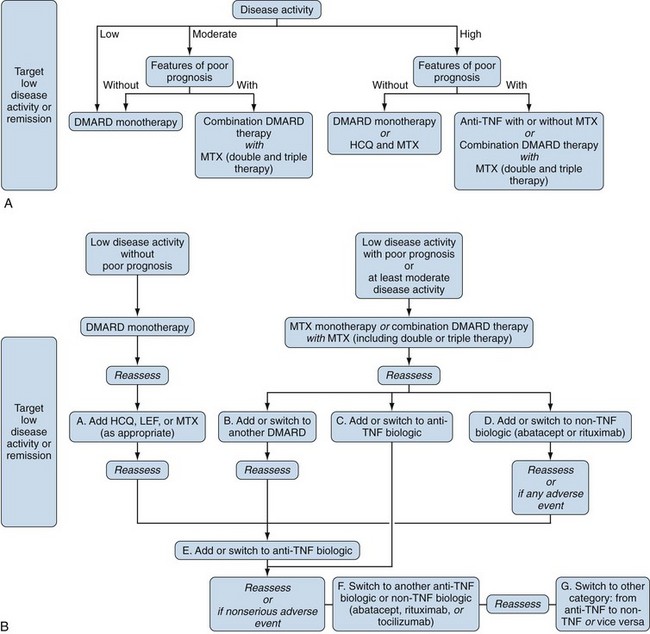

As detailed earlier, the goal of treatment for all RA patients is remission or at least low disease activity; other than toxicity concerns and affordability issues, clinicians should not care which drug or combination of drugs are used in an individual patient but should focus on getting patients to target with whatever it takes. There is no magic or correct DMARD or combination of DMARDs that is right for all patients. Each patient presents a unique challenge and comes with unique expectations, biases, disease activity level, damage burden, comorbidities, and insurance coverage issues. One of the most important areas of investigation in RA is to identify parameters that will predict in a differential fashion which patient will respond to which therapy—so far no clear-cut answers that are applicable to the clinical care of the vast majority of patients have emerged. Some have suggested treatment should be different for RA patients with good prognosis versus poor prognosis. This concept is problematic; separating patients into good versus poor prognosis is difficult. Although data suggest certain features are associated with worse prognosis (Table 71-5), unfortunately no data suggest that stratifying our therapies on the basis of prognosis at the individual patient level yields better outcomes. For example, if we could perfectly score prognosis on a scale of 1 to 10, those patients with intermediate scores would conceivably benefit the most from our most aggressive therapies while those with low scores do not need them and those with the highest scores may have an unacceptable benefit-to-toxicity ratio. Most patients who meet criteria for classification of RA in clinic and essentially all of those included in clinical trials have poor-prognosis RA with multiple factors listed in Table 71-5. Regardless of the prognostic factors, the goal for each patient is to achieve at least low disease activity. Until or unless parameters are identified, rheumatologists will of necessity continue to use their clinical judgment at the individual patient level.

Table 71-5 Factors Associated with Poor Prognosis in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Without parameters that predict in a differential way response to medications in terms of efficacy or toxicity, one approach to treatment decisions is illustrated in Figure 71-3. Note that several iterations may be required. This figure indicates that we do not have these much-needed parameters and emphasizes that if we hope to treat RA in a rational, scientific way, it is critical to find these parameters. Figure 71-3 also highlights and reinforces the need to include bio-banks with all of our clinical trials. With regard to individual patients, Figure 71-4 (ACR recommendations2) is perhaps a more practical approach. Specific patient populations are discussed as follows.

Figure 71-3 One approach to selecting therapy for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients.

(Courtesy of James R. O’Dell and Robert Wigton, MD.)

Treatment of the DMARD-Naïve Patient

The most critically important principle of treating RA effectively is to initiate and rapidly advance DMARD therapy as early as possible. Although this is a universally accepted principle, there is a paucity of rigorous data that directly addresses this point. Few randomized double-blind trials62–65 in which patients are randomized to early treatment versus late treatment have been conducted, and it is unlikely, not to mention unethical, that any more will be forthcoming. Rather, we accept this foundation principle on the basis of the common and firm belief that treating patients early prevents damage and deformity and preserves function. Many trials and case series provide strong, credible evidence to support this central tenet. Evidence to support this commonsense belief comes from cohort studies of early versus delayed therapy,66 randomized studies of intensive therapy versus usual care,18 RCTs of combination versus monotherapy,19,20,29,67–71 and finally studies of what was previously defined as preclinical RA.65

One cohort study of note reported on early RA patients. The first cohort received DMARD therapy early (mean, 123 days after diagnosis), whereas the second cohort received DMARDs very early (mean, 15 days after diagnosis66). The first cohort had significantly more radiographic damage at 2 years and, importantly, continued to have radiographic progression while the second did not. The findings of the TICORA trial (detailed earlier18) clearly show the advantages of better control of disease earlier. Multiple studies in early RA have demonstrated that when groups of patients are compared, those that get combinations of therapy fare better than those that get monotherapy.19,20,29,67–71 COBRA with the combination of MTX, SSZ, and prednisolone versus SSZ alone29; FINRACO67with the combination of MTX, SSZ, HCQ, and prednisone versus SSZ; BeSt with the multiple combinations compared with step-ups or switches19,20; ATTRACT69 with the combination of infliximab and MTX versus MTX alone and PREMIER with the combination of adalimumab and MTX versus each alone are some examples of these.70 In all these trials, the combinations outperformed monotherapy.

The PROMPT trial65 addressed a somewhat different question—patients with inflammatory arthritis who could not yet be classified as RA were randomized to MTX treatment or placebo, and the end point was the development of clinical RA. The MTX-treated group had significantly delayed progression to full-blown RA. Taken together, all these data make a compelling argument for early DMARD therapy in RA.

The new ACR/EULAR RA classification criteria12 should allow us to classify patients with RA earlier and therefore treat RA patients earlier. The criteria, discussed in detail in Chapter 70, were designed to allow rheumatologists to classify patients in clinical trials with RA as early as possible. Gone is the previous absolute requirement that all patients must have certain features for a minimum of 6 weeks before classification. The 6-week threshold is still acknowledged as important but no longer required, and many patients, particularly those with poor prognostic features, will fulfill criteria before 6 weeks. Importantly, the presence of anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs), particularly higher-titer antibodies, is weighed heavily in the new criteria (two points). Of note in the previously mentioned PROMPT trial,65 the benefit of early MTX was seen only in patients who were ACPA positive. Most, if not all, of these patients in PROMPT would fulfill new criteria for classification as RA, so PROMPT can be thought of as a trial to test the very early treatment of RA versus the delayed approach.

The First DMARD

Accepting that DMARD therapy should be started as early as possible, which DMARD should be started? And should we begin with mono or combination DMARD therapies? Although many of the previously cited studies have shown that combinations outperform monotherapy in randomized controlled trials, this does not mean that initial combination therapy should be the standard approach for all patients in the clinic. Most clinicians initially start most patients on mono-DMARD therapy; the evidence to support this is discussed later and is validated by the recent findings of the Treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid (TEAR) trial.71 The decision of which DMARD to initiate at the individual patient level is complex, and at this time there is clearly no one right answer for all patients and all clinical situations (see Figure 71-3 or 71-4A)—one size, or in this case one drug, clearly does not fit all. Many factors need to be considered including, but not limited to, the patient’s disease activity, comorbidities and preference, the relative expense to the patient and to the health care system (weighing the benefits and including direct and indirect costs in our thinking) and importantly where relevant, the patient’s desire (both female and male) to conceive. Until or unless parameters that allow selection on the basis of data become available, this complicated decision will still require the best of the clinician’s judgment.

With all this said, MTX should be the initial DMARD for the majority of patients. MTX is inexpensive (see Table 71-4), effective, well-tolerated, and, importantly, is the cornerstone of most successful combination therapies (see Figure 71-2). In particular, excellent data exist that anti-TNF therapy with all the currently available agents is much more effective with MTX on board both in terms of clinical and radiographic outcomes71–74 (see Chapter 61 for specific details on MTX). MTX is usually administered orally at first, although subcutaneous dosing has more predictable bioavailability. In most cases, the dose should be pushed to a minimum of 20 to 25 mg/week if necessary to control disease unless there are contraindications or tolerance problems. Most studies have shown that maximum efficacy may take up to 6 months to achieve but that in most situations, the response at 3 months predicts ultimate success. If MTX is used in this way, approximately 50% of patients will have a good response, and according to consistent data from several trials, approximately 30% will achieve low disease activity status.18,19,71,74

Initiating Treatment with a Single DMARD versus Combinations of DMARDs

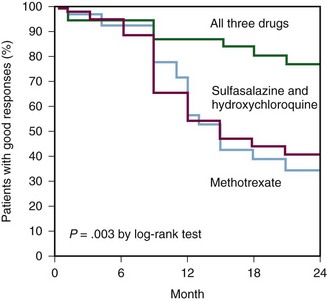

Although most clinicians still favor starting with monotherapy, combination DMARD therapy has clearly changed the treatment of RA forever. In the early 1990s, the treatment model called for individual DMARDs and then switching to a different DMARD when necessary. At that time, combinations of DMARDs were not used. Studies published in the mid-1990s showing the impressive efficacy and tolerability of various combinations of DMARDs dramatically changed the treatment paradigm.44,75 Now the majority of RA patients are treated with combinations of two, three, or more DMARDs. The first study that put combination DMARD therapy on the map was the so-called triple therapy study by the RAIN group of investigators.75 This study clearly demonstrated that the triple combination of MTX, HCQ, and SSZ was significantly more effective than MTX alone or the combination of HCQ and SSZ (Figure 71-5). Importantly, this combination of DMARDs did not lead to any increase in toxicity. Multiple publications on other successful combinations of conventional DMARDs soon followed.29,33,44,67,68,76

Today, the important question of whether all patients should be started on combinations of DMARDs and then stepped-down or whether started on monotherapy initially and then stepped-up only if patients are not at target is an ongoing debate. Both approaches have their supporters, and data can be presented on both sides of this question. On the one hand, there is no doubt that if short-term responses are looked at in groups of patients, combinations outperform monotherapy. This is true for combinations of conventional DMARDs,29,67,68 as well as combinations of conventional DMARDs with a biologic.70 On the other hand, the strategy of initial monotherapy with step-ups only in patients who need it was clearly effective in TICORA (as discussed earlier18) and importantly in the BeSt trial19,20 and TEAR trials (discussed later71), and although initial responses were better in both of the latter trials in the clinical parameters of patients initially treated with combinations, all groups in both BeSt and TEAR had identical DAS or DAS28 scores at the end of 2 years. Clinicians do not treat groups of patients but individual patients, and if the results are similar at 2 years or beyond, effective treatment approaches that minimize the number of DMARDs and therefore their potential toxicities and certain expense will be desirable for patients and health care systems alike.

BeSt (Dutch Acronym for Behandel-Strategieen, “Treatment Strategies”) Study

BeSt continues to be an important randomized, multicenter trial in which 508 early RA patients were randomized to receive one of four treatment “strategies” in an open-label study.19,20,77 The four arms of the study were as follows:

• Group 1: Sequential DMARD monotherapy; initial MTX 15 mg/week → MTX 25 to 30 mg/week → SSZ → Lef → MTX + infliximab → etc.

• Group 2: Step-up combination therapy; initial MTX 15 mg/week → MTX 25 to 30 mg/week → MTX + SSZ → MTX + SSZ + HCQ → + MTX + SSZ + HCQ + prednisone → MTX + infliximab → etc.

• Group 3: Initial combination therapy; initial MTX 7.5 mg/week + SSZ 2000 mg/day + prednisone 60 mg/day (tapered to 7.5 mg/day by 7 weeks) → MTX 25 to 30 mg/week + SSZ + prednisone → MTX + CSA + prednisone → MTX + infliximab → etc.

• Group 4: Initial MTX and infliximab; initial MTX 25 to 30 mg/week + infliximab 3 mg/kg → infliximab 6 mg/kg every 8 weeks → infliximab 7.5 → infliximab 10 mg/kg every 8 weeks → etc.

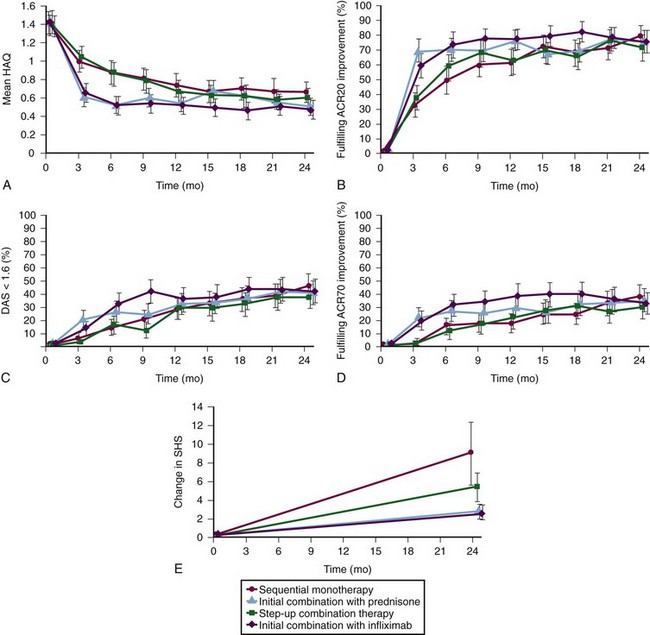

Treatment adjustments were made every 3 months with the target of a DAS less than or equal to 2.4 (low disease activity). The DAS is calculated using four variables: Richie Articular Index (66 tender joint count [RAI]), swollen joint count (44 joints [SJC]), the ESR (mm/hour), and the global health assessment score (0 to 100; [GH]); DAS = .53938 × √RAI + .06465 × (SJC) + .33 × ln(ESR) + .00722 × (GH). The major results at 1 and 2 years are shown in Figure 71-6—both combination groups (Groups 3 and 4) improved quicker than Groups 1 and 2, which was expected with high-dose prednisone in Group 3 and high-initial-dose MTX and also infliximab in Group 4. At 1 year, DAS and other clinical outcomes were similar in all four groups and, importantly, at 2 years they were identical. Health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) scores improved more in the early combination groups (Groups 3 and 4) at 1 year but were not different at 2 years, and radiographic progression at 2 years was greater in Group 1 than in Group 2 and greater in Groups 1 and 2 than in the combination groups (mean modified Sharp van der Heijde Score progression of 9, 5.2, 2.6, and 2.5, respectively). Progression of the joint space narrowing score (importance discussed later), although numerically higher in Group 1, was not statistically different among the four groups (4.3, 2.1, 1.5, 1.2, respectively). Interpretation of these differences is complicated by the fact that despite only 6 months of disease, Group 2 had more radiographic progression at baseline.

Conclusions from BeSt

1. The strategy of adding DMARDs as in Group 2 was more effective than the strategy of switching from one DMARD to another, at least for the DMARDs and their order of use in BeSt. Although the clinical outcomes were similar at 2 years for these groups, radiographic progression was greater in Group 1 (mean 9 vs. 5.2), more Group 1 patients required infliximab (26% vs. 6%), and many Group 1 patients ended up on combinations anyway.

2. Initial therapy with combinations of conventional DMARDs (Group 3) or combinations including biologics (Group 4) work more quickly than step-up therapy (Group 2). However, at 2 years, the clinical results were identical. There was a statistical advantage of the combination groups over the step-up group in terms of total radiographic progression (Δ 2.5 points over 2 years); there was no difference in terms of joint space narrowing. This difference in radiographic progression is of no clinical significance unless it continues to grow at similar rates for years. More strategies need to be employed to further change therapies on the basis of radiographic progress in the small group (perhaps 10%) of patients on only conventional therapy where it is relevant.

3. A subset of patients was able to discontinue drug therapy for a period of time. In BeSt, if a DAS score of less than 1.6 was achieved for 6 months, patients were tapered off all medications—this occurred in 115 (23%) of patients. Although many patients relapsed, 59 patients (11.6%) were in remission off all treatment (median follow-up 23 months77).

Treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid (TEAR) Trial

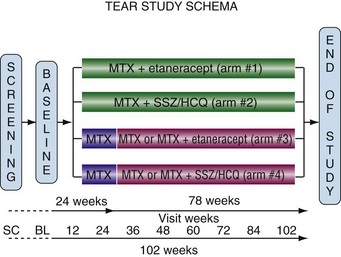

The TEAR trial was a landmark study of initial DMARD therapy in patients with early (mean disease duration = 3.6 months), poor-prognosis (all RF positive, CCP positive, or erosive) RA.71 It is the largest (n = 755) investigator-initiated, randomized, double-blind trial in RA to date. TEAR was a 2-year study and sought to address two critical questions in this early RA population:

1. Should patients be initiated on combination therapy or stepped-up to combinations only after a trial of MTX monotherapy?

2. Is combination therapy with MTX-ETAN superior to therapy with MTX-SSZ-HCQ (triple) therapy?

The 755 patients were randomized to the four groups as illustrated in Figure 71-7. Randomization was done in a 2 : 1 ratio with twice as many patients randomized to the ETAN groups. Patients randomized to the MTX-only groups were stepped-up (72% of patients stepped-up) to their assigned combination at 6 months in a blind fashion unless their DAS28 scores were less than 3.2.

Figure 71-7 Schematic of the four different treatment groups in the TEAR trial.71 Patients in arms 3 and 4 were treated with methotrexate (MTX) alone and step-up at 24 weeks if DAS28 was greater than 3.2. BL, baseline; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; SC, screening; SSZ, sulfasalazine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree