Fig. 19.1

(a) Photograph of the experiment creating a Hill–Sachs lesion. The humeral head was compressed to the square sawbone simulating the glenoid. (b) A created Hill–Sachs lesion. The Hill–Sachs lesion was artificially created on the humeral head by compressing the sawbone

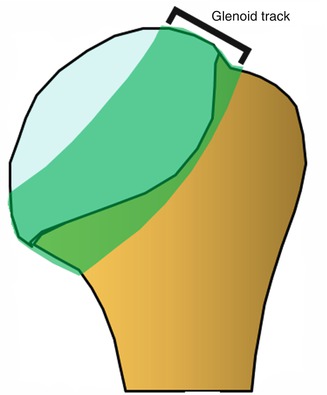

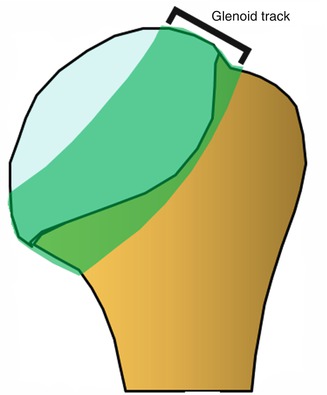

We clarified, in a biomechanical study using fresh cadavers, which Hill–Sachs lesion is risky by determining the location of the glenoid on the humeral head with the arm elevating along the posterior end range of motion [12]. As the arm was elevated with maximum external rotation and horizontal extension, the contact area of the glenoid shifted from the inferomedial to the superolateral portion of the posterior aspect of the humeral head, creating a zone of contact. We defined this contact zone as the “glenoid track” (Fig. 19.2). According to the measurements in cadaveric shoulders, the glenoid track width was equal to 84 % of the glenoid width in cadaveric shoulders [12] and 83 % in live shoulders [7]. With use of this glenoid track concept, we have proposed to evaluate the risk of engagement with the glenoid [4]. If a Hill–Sachs lesion is located more medially over the medial margin of the glenoid track, such a lesion needs to be treated. On the other hand, if a Hill–Sachs lesion stays on the glenoid track, there is no risk of engagement between the Hill–Sachs lesion and the anterior rim of the glenoid. Such a lesion needs no treatment.

Fig. 19.2

Glenoid track. As the arm was elevated with maximum external rotation and horizontal extension, the contact area of the glenoid shifted, creating a zone of contact. We defined this contact zone as the “glenoid track”

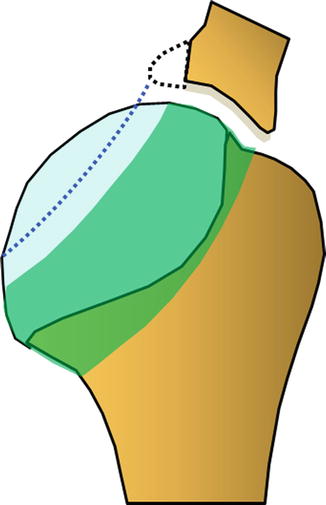

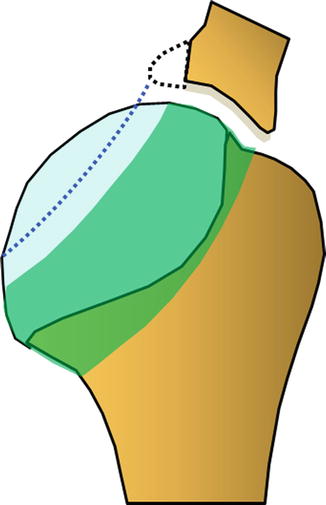

Engagement between a Hill–Sachs lesion and the glenoid rim occurs in 100 % of the cases theoretically because the Hill–Sachs lesion is the result of engagement. This means both the Hill–Sachs lesion and the glenoid are responsible for engagement, not just one or the other. In fact, the engagement is known to be observed more frequently if there is a large glenoid defect [13]. Therefore, when we consider the critical size of the Hill–Sachs lesion, we also have to consider the bony defect of the glenoid at the same time. Our new concept, the “glenoid track,” enables us to take both lesions into consideration. If there is a glenoid defect, the defect width should be subtracted from 83 % of the glenoid width (Fig. 19.3).

Fig. 19.3

Glenoid track when there is a glenoid defect. If there is a glenoid defect (dotted line), the defect width should be subtracted from 83 % of the glenoid width

Previously, we referred to the lesion as an “engaging” or “nonengaging” Hill–Sachs lesion. However, this terminology is confusing because a lesion that engages before the Bankart repair usually becomes a nonengaging lesion after the Bankart repair. Only 7 % of all the Hill–Sachs lesions remained as an engaging lesion after the Bankart repair [8]. In order to avoid this confusion, Di Giacomo et al. proposed a new terminology “on-track” and “off-track” lesion [3]. A Hill–Sachs lesion that stays on the glenoid track, which means there is no risk of engagement after the Bankart repair, is an “on-track” lesion, whereas a Hill–Sachs lesion that extends out of the glenoid track, which means there is a risk of engagement even after the Bankart repair, is an “off-track” lesion.

19.3 Clinical Presentation

Case 1

A 51-year-old female sustained a traumatic dislocation of her left shoulder after a fall down the stairs. She reported 15 subsequent episodes of dislocation since then. She had a small glenoid defect (3 mm in width) and a large Hill–Sachs lesion (86 % of the glenoid width), which was located off the glenoid track (off-track lesion) (Fig. 19.4a, b). We performed arthroscopic remplissage procedure combined with the Bankart repair. One and a half years after the surgery (Fig. 19.5), she has had no re-dislocation and enjoys playing golf although she has a mild limitation in the range of external rotation (20° each in adduction and in abduction).

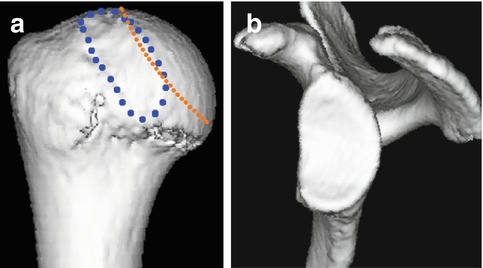

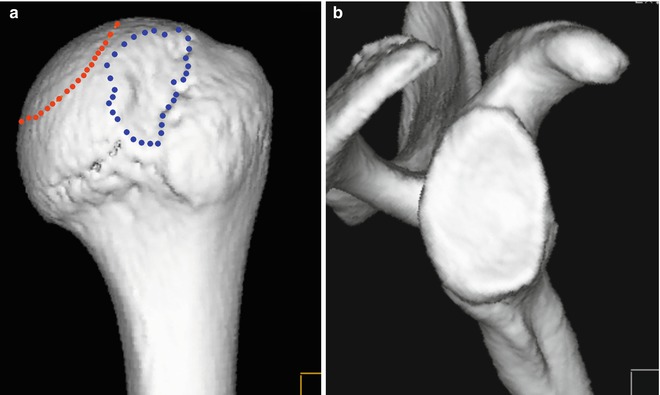

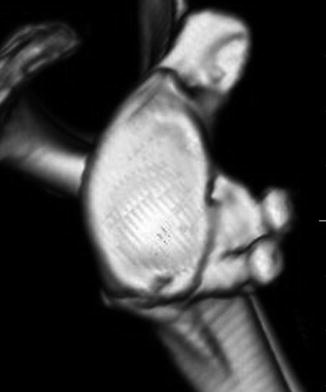

Fig. 19.4

(a) 3D CT image of the humeral head. This Hill–Sachs lesion (blue dotted line) was located more medially over the glenoid track (orange dotted line). (b) 3D-CT image of the glenoid. The size of the glenoid bony defect was 3 mm in width, a small defect

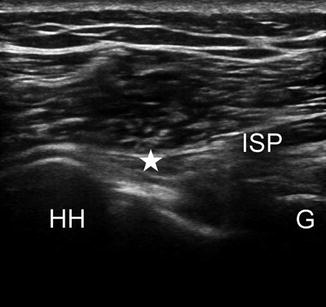

Fig. 19.5

Posterior view of the postoperative ultrasonographic image. The infraspinatus (ISP) tendon (★) is fixed into the humeral head (HH) defect. G glenoid rim

Case 2

An 18-year-old, right-hand-dominant male initially dislocated his left shoulder during a rugby game. He reported three subsequent episodes of dislocation during rugby games. He had a large glenoid defect (23 % of the glenoid width) and a large Hill–Sachs lesion (80 % of the glenoid width), which was within the glenoid track but very close to the medial line of the glenoid track (Fig. 19.6a, b). We performed the Latarjet procedure for this patient. Two years after the surgery (Fig. 19.7), he had neither restriction of the range of shoulder motion, recurrence, nor anterior apprehension. He could return 100 % to his previous level.

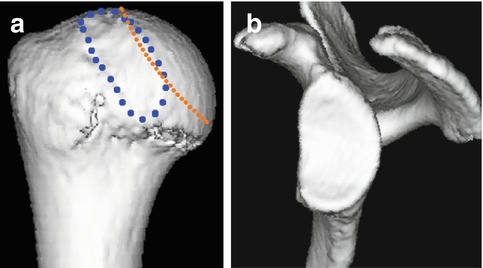

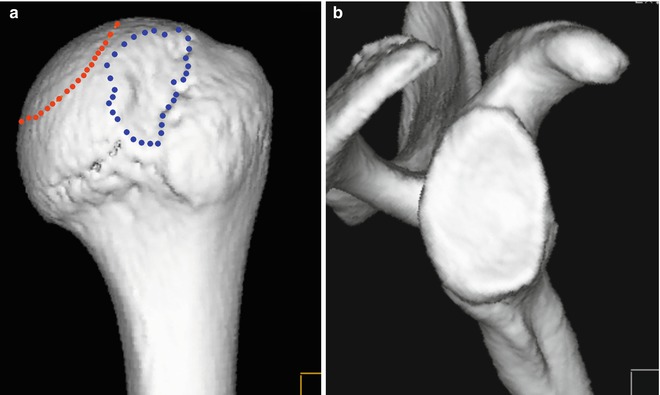

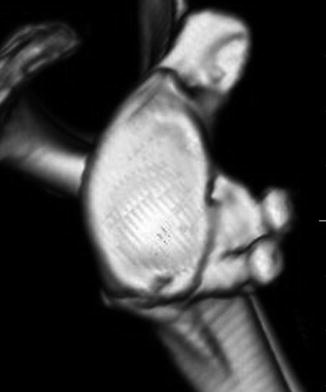

Fig. 19.6

(a) A large Hill–Sachs lesion. There was a large Hill–Sachs lesion (blue dotted line), which was within the glenoid track (orange dotted line) but very close to the medial margin of the glenoid track. (b) Large glenoid track. The size of the glenoid bony defect was 4.5 mm in width, which was 23 % of the glenoid width compared to the uninvolved side

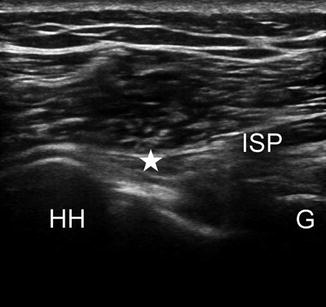

Fig. 19.7

Postoperative 3D CT image. Union of the grafted bone was observed

19.4 Essential Radiology

19.4.1 X-ray

We advocate three views: (1) an AP view to evaluate the bony fragment of the glenoid, (2) an axillary view (glenoid bony defect or fracture or a Hill–Sachs lesion), and (3) a Stryker notch view (a Hill–Sachs lesion). However, unfortunately, x-ray is not reliable for the accurate assessment of the size of the Hill–Sachs lesion.

19.4.2 CT (3D-CT)

This gives a lot of information on bony lesions, but a small Hill–Sachs lesion and an erosion-type glenoid defect may not always be recognized. In such cases, three dimensionally reconstructed computed tomography (3D-CT) with the humeral head eliminated is useful and gives excellent information. Sagittal and axial CT images or 3D-CT images of bilateral shoulders are useful and reproducible in measuring the size of the Hill–Sachs lesion. We routinely perform 3D-CT and magnetic resonance arthrography in patients with recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree