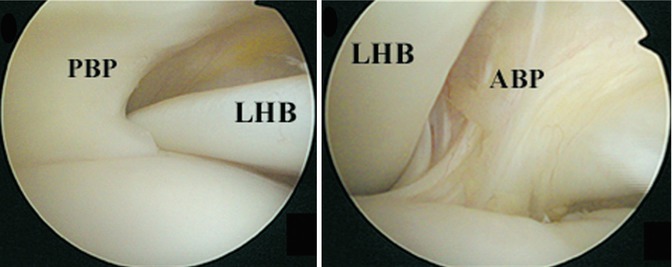

Fig. 24.1

Anatomy of the biceps pulley. The CHL and SGHL blend together with the upper fibers of the subscapularis anteriorly, while the CHL blends with the anterior fibers of the supraspinatus posteriorly. The fasciculus obliquus (not pictured here) forms the roof of the sling (Reprinted with permission Habermeyer et al. [13])

While there is a general consensus that the biceps is a common pain generator in the shoulder, the function of the biceps has been debated in the literature and is not completely understood. It has been reported to serve as a dynamic stabilizer in the unstable shoulder as well as a dynamic depressor and restraint to external rotation of the humeral head during abduction in the stable shoulder [8–10].

Biceps pulley lesions can result from either a degenerative or traumatic process, which typically results from a fall on the outstretched arm (in combination with full external or internal rotation), a fall backward on the hand or elbow, or a forcefully stopped overhead throwing motion [11]. Gerber and Sebesta first described the concept of anterosuperior impingement of the shoulder whereby there is contact between the upper subscapularis, biceps pulley, and LHBT with the anterosuperior glenoid rim [12]. They suggested that this phenomenon can lead to lesions of the upper subscapularis (involving the articular fibers) and/or anterior biceps pulley that can result in biceps instability, a finding supported by Habermeyer et al. [13]. Boileau et al. have suggested that a hypertrophic “hourglass” biceps may lead to pathologic stretching of the biceps pulley, thereby causing symptomatic instability of the tendon at its entrance to the bicipital groove [14]. Baumann et al. have suggested that biceps pulley lesions are progressive in nature and ultimately lead to adjacent rotator cuff tearing at the rotator interval [11].

Depending on the location of the pulley lesion, instability of the biceps tendon may be present anteromedially, posterolaterally, or anteroposteriorly [15, 16]. While dislocations of the LHBT have been described in either an anteromedial or posterolateral direction, subluxations can occur anteromedially, posterolaterally, or anteroposteriorly [15, 16]. When the tendon sits or can be manipulated out of its normal position as it enters the bicipital groove without passing over the greater or lesser tuberosity, it is defined as a subluxation. Conversely, when the tendon rests or can be manipulated completely out of the bicipital groove and over the greater or lesser tuberosity, it is defined as a dislocation. Furthermore, biceps instability can be present either with or without concomitant rotator cuff lesions. While anteromedial subluxation can be secondary to an isolated lesion of the anterior biceps pulley (i.e., SGHL), anteromedial dislocation has only been reported in the presence of associated tearing of either the supraspinatus or subscapularis [3, 15–17]. Partial tearing of the superior fibers of the subscapularis appears to be more commonly associated with anteromedial dislocation versus subluxation of the LHBT [15, 16]. Slätis and Aalto demonstrated that disruption of the CHL was the key anatomic finding that led to anteromedial instability of the biceps tendon in the presence of a supraspinatus tear [17]. All cases of anteromedial dislocation were found to have an associated full-thickness supraspinatus tear, while all cases of anteromedial subluxation were found to have a partial-thickness tear of the anterior supraspinatus. In all of their cases of anteromedial dislocation, they noted the biceps tendon was dislocated along the ventral (anterior) surface of the subscapularis. No associated lesions were reported in the SGHL or subscapularis. However, their anatomic description of the CHL included all tissues between the superior border of the subscapularis and anterior border of the supraspinatus and therefore likely included some portion of what is now termed the SGHL. Walch et al. described anteromedial instability of the LHBT in the presence of a full-thickness supraspinatus tear and an associated “hidden lesion” of the deep fibers of the CHL, SGHL, and upper subscapularis [3]. In all of their cases, the LHBT was located along the deep (posterior) surface of the upper subscapularis tendon. It is reasonable to deduce that the location of an anteromedial biceps tendon dislocation (ventral or deep surface of the subscapularis) is dictated by the integrity of the deep fibers of the CHL, SGHL, and superior fibers of the subscapularis.

Isolated posterolateral instability of the LHBT is generally secondary to disruption of the posterior biceps pulley consisting mostly of the CHL as it blends with the anterior fibers of the supraspinatus [5, 15]. This can be seen in association with either a partial- or full-thickness tear of the supraspinatus involving the far anterior tendon footprint [15]. Anteroposterior biceps instability occurs as a result of a lesion to the anterior and posterior biceps pulley and is highly associated with tears of both the anterior supraspinatus and subscapularis involving at least the upper one-third of the tendon [15, 16].

24.3 Classification

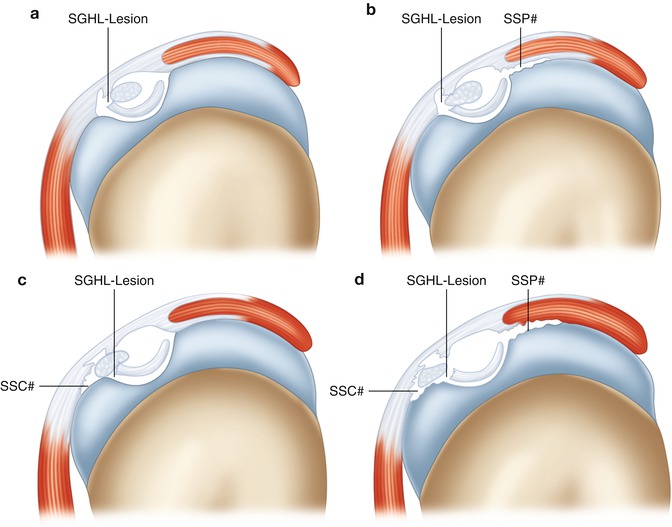

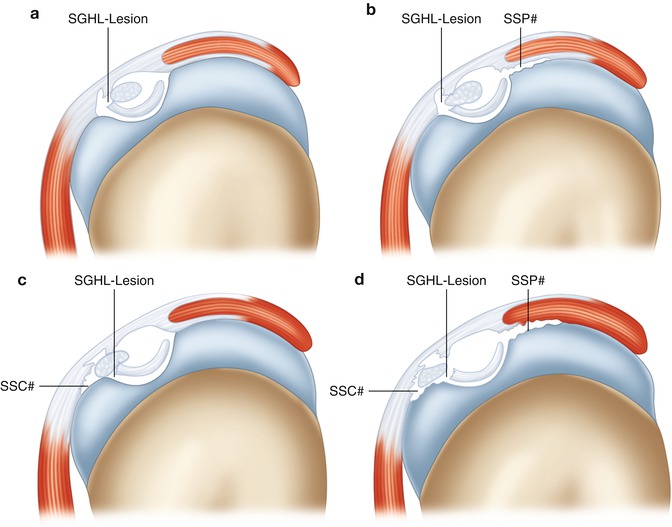

Several authors have proposed classification systems for biceps pulley lesions. Habermeyer et al. described lesions of the biceps pulley leading to anteromedial instability of the biceps tendon in association with anterosuperior impingement of the shoulder (Fig. 24.2) [13]. Group 1 consisted of isolated lesions of the SHGL; group 2 consisted of SGHL and partial articular-sided tears of the supraspinatus; group 3 involved the SGHL and partial articular-sided tears of the subscapularis; and group 4 involved the SGHL and partial articular-sided tears of both the subscapularis and supraspinatus.

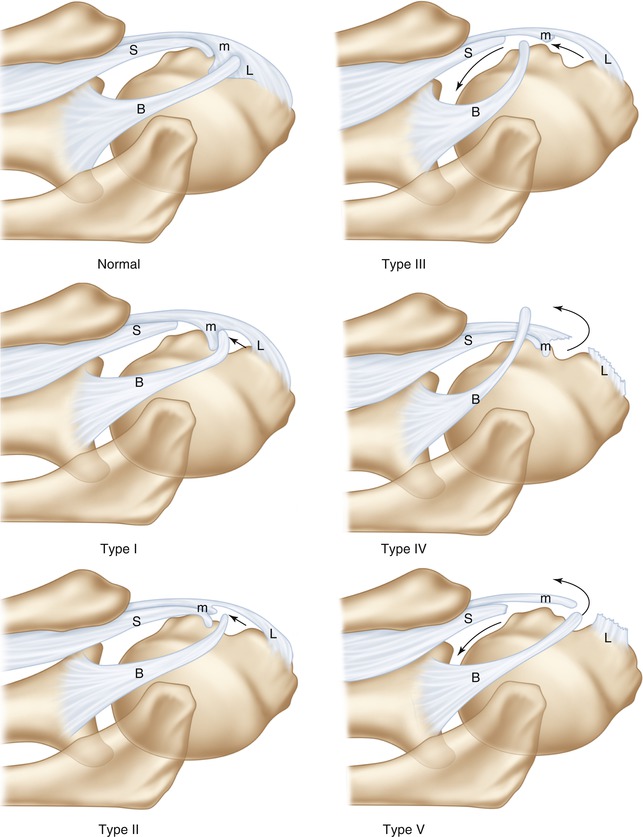

Fig. 24.2

Classification of biceps pulley lesions according to Habermeyer et al. (a) Isolated SGHL lesion. (b) SGHL lesion and partial articular-sided supraspinatus tear. (c) SGHL lesion and partial articular-sided upper supraspinatus tear. (d) SGHL lesion and partial articular sided tear of the upper subscapularis and supraspinatus. (Reprinted with permission Habermeyer et al. [13])

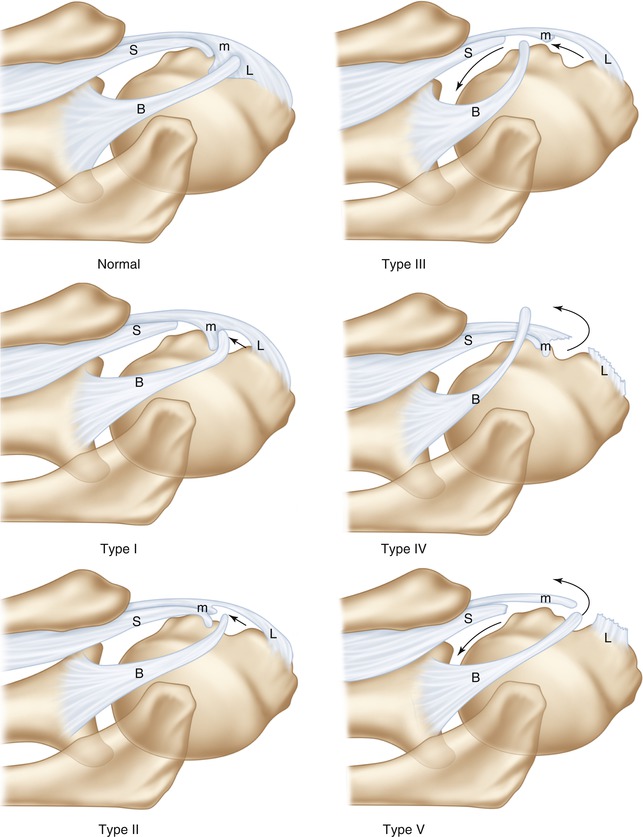

Bennett proposed a slightly more detailed classification of rotator interval lesions in the presence of an anterosuperior (supraspinatus and subscapularis) rotator cuff tear that allows for anteromedial biceps subluxation/instability (Fig. 24.3) [18]. Type 1 lesions involve tears of the subscapularis without involvement of the medial fibers of the CHL. Type 2 lesions result from tearing of the medial fibers of the CHL without a tear of the subscapularis. Type 3 lesions result from concomitant tears of the subscapularis and medial fibers of the CHL. Type 4 lesions involve the posterior biceps pulley consisting of tears of the supraspinatus and the lateral fibers of the CHL. Type 5 lesions result from tearing of the anterior and posterior pulley and involved the subscapularis, with medial and lateral fibers of the CHL and the leading edge of the supraspinatus tendon.

Fig. 24.3

Classification of rotator interval lesions according to Bennett (Reprinted with permission Bennett [18])

More recently, Lafosse et al. described an arthroscopic classification of LHBT instability in patients with rotator cuff tears [15]. Their classification scheme allows for stratification according to the degree of instability (subluxation vs dislocation), direction of instability (anterior, posterior, or combined anteroposterior), macroscopic appearance of the LHBT, and integrity of the adjacent rotator cuff tendons. This was the first proposed classification system to highlight the importance of posterolateral instability of the LHBT.

24.4 Clinical Presentation and Essential Physical Exam

As with all patients presenting with a chief complaint of shoulder pain, a careful history is essential to accurately determine the proper diagnosis. Patients with LHBT instability can be challenging to evaluate as there is no one specific component of the history we are aware of that is unique to this population. As previously noted, biceps pulley lesions can be caused by either trauma or degenerative changes. If the onset is traumatic in nature, particular attention should be paid to the mechanism of injury. Pulley lesions can be a result of a fall on an outstretched arm (in combination with internal or external rotation), a fall backward on the hand or elbow, or a forcefully stopped overhead throwing motion of the arm [13]. Pain can often be diffuse and nonspecific or located in the anterior or anterolateral aspect of the shoulder. Some patients may complain of a “deep” pain in the front of the shoulder. Associated clicking or popping of the shoulder may or may not be present.

Physical examination of patients with suspected biceps pathology can be particularly challenging. Numerous tests have been described in the literature, but currently there is no single one that serves as the gold standard. Pain may be present when palpation is done along the bicipital groove, but this can be nonspecific. O’Brien’s, Speed’s, and Yergason’s tests have not been shown to have very good sensitivity or specificity in differentiating biceps pathology from SLAP tears [15, 19]. However, Kibler et al. have demonstrated that the combination of a positive Speed’s and upper cut tests is significantly better at detecting isolated biceps pathology separate from SLAP tears [20]. Rotator cuff strength testing may reveal pain and/or weakness if associated tearing is present. In particular, the belly-press test may be positive if the SGHL/upper subscapularis is involved. However, positive provocative tests for rotator cuff pathology do not definitively rule in a biceps pulley lesion.

Bennett has previously described a provocative maneuver called the biceps subluxation test in order to better delineate lesions resulting in biceps instability [18, 21]. To perform this test the patient’s arm is held in 90° of abduction and full external rotation. The arm is then passively brought into full cross-body adduction and internal rotation in an effort to elicit subluxation of the biceps tendon within the sheath. The test is considered positive if the patient relates the sensation of pain, slipping, catching, or popping during the passive range. We are not aware of any studies in the literature that serve to validate this test.

Currently there is no literature present on the diagnosis of biceps pulley lesions specifically in the overhead athlete. However, when treating such patients, we feel it is important to take time to review pitch count, types of pitches being thrown, and how often they are throwing/pitching throughout the year. It is also important to determine which phase of throwing and at what arm position their pain ensues.

We prefer to perform a diagnostic injection with 1 % lidocaine into the glenohumeral joint in the office setting for patients with suspected biceps pathology based on history and physical examination. This injection is done under sterile conditions from an anterior approach halfway between the tip of the coracoid process and acromion. After a few minutes, the amount of relief reported by the patient is noted and can serve as a helpful tool for either raising or lowering the index of suspicion for biceps pathology.

24.5 Essential Radiology

Despite the inherent challenges noted above, a through history and physical examination should provide an accurate level of suspicion for biceps pathology/biceps pulley lesion. We feel that the radiographic examination should be obtained to confirm the appropriate diagnosis and rule out any additional pathology that may also need to be addressed during surgery. We begin with plain radiographs on all patients consisting of anteroposterior (AP) views in internal and external rotation along with axillary lateral and outlet views. Subtle cystic erosion involving the lesser tuberosity has been previously reported in patients with “hidden lesions” of the rotator interval; however, we are not aware of any other plain radiographic findings specific for lesions of the biceps pulley [3].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a helpful tool to assess for a biceps pulley lesion, LHBT instability, as well as associated rotator cuff pathology. Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) has been shown to be more sensitive and specific for rotator cuff and rotator interval pathology, and this remains our study of choice in evaluating for a biceps pulley lesion [22, 23]. Optimal MR imaging should include images obtained in all three planes and aligned with the glenohumeral joint. Since MRA is a static image, it may not demonstrate clear evidence of biceps tendon instability depending on the extent of the pathology and the position of the arm at the time of the study [15, 21]. We pay particular attention to the T1- and T2-weighted axial and sagittal oblique image sequences to evaluate the contents of the rotator interval and biceps pulley for pathology that would be suggestive of biceps instability (Fig. 24.4). We find the axial and coronal sequences more helpful for evaluating associated tearing of the rotator cuff. The axial images are principally used to evaluate for anteromedial biceps tendon subluxation or dislocation in conjunction with an upper subscapularis lesion and should be carefully considered when deciding on proper surgical treatment (Fig. 24.5). Of note, if patients cannot undergo MRA for any reason, then we use CT arthrogram as our preferred imaging test.

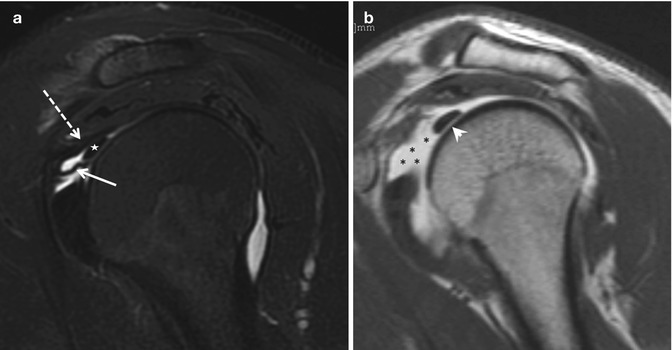

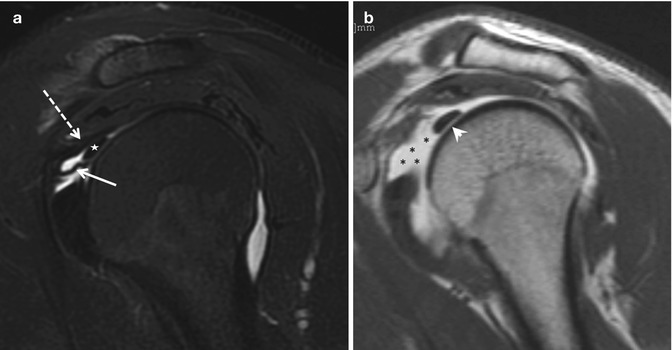

Fig. 24.4

(a) Oblique sagittal fat-saturated T2-weighted images showing the biceps tendon (star), SHGL (white arrow), and CHL (dotted white arrow). (b) Oblique sagittal fat-saturated T1-weighted images demonstrating biceps tendon (white arrowhead) with a tear of the SGHL (black stars) (Reprinted with permission Zappia et al. [26])

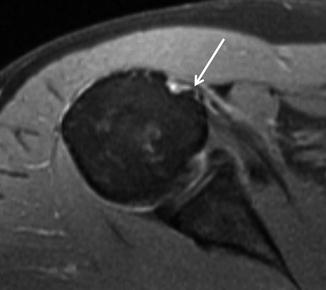

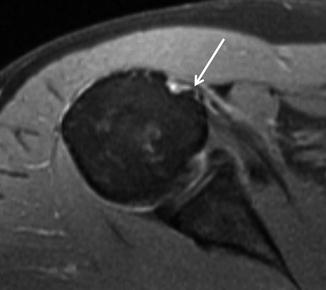

Fig. 24.5

Axial T2-weighted MRI of a patient with anteromedial biceps instability. The long head of the biceps tendon is flattened and perched on the lesser tuberosity (white arrow). The subscapularis origin showed mild tendinosis

Ultrasound has recently gained increased popularity amongst orthopedic surgeons in the diagnosis of shoulder pathology. This modality has shown good utility in diagnosing rupture, subluxation, or dislocation of the biceps tendon but poor accuracy in diagnosing small partial-thickness tears or fraying of the intra-articular LHBT [24, 25].

24.6 Disease-Specific Clinical and Arthroscopic Pathology

It is our feeling that diagnostic arthroscopy is the “gold standard” for accurate diagnosis of biceps pulley lesions and biceps instability. Despite the high sensitivity and specificity of MR arthrography for lesions of the biceps pulley, it represents a static image for a potentially dynamic problem and in our experience can be inadequate if the images are not perfectly aligned with the glenohumeral joint. We begin with visualization of the biceps tendon and its position within the glenohumeral and entrance to the bicipital groove. The ramp test is then performed as described by Motley et al. to assess for anteromedial instability of the biceps tendon [27]. We then visualize the anterior and posterior biceps pulley for any tearing and use an arthroscopic probe to manually test for anteromedial or posterolateral biceps subluxation/instability (Fig. 24.6). This is followed by dynamic evaluation of the biceps tendon as described by Lafosse et al. in slight abduction with external and internal rotation to test for anteromedial and posterolateral biceps instability, respectively [15]. In the presence of what appears to be an isolated supraspinatus tear, careful attention must be directed to the rotator interval for evidence of a “hidden lesion” involving the CHL, SHGL, and upper subscapularis as described by Walch et al. [3]. This can result in anteromedial instability of the biceps tendon and should be treated with biceps tenodesis and possible subscapularis repair depending on the extent of its involvement. In patients with an anterosuperior (subscapularis and supraspinatus) rotator cuff tear, careful attention should be directed to the anterior and posterior biceps pulley for evidence of biceps instability.