Fig. 29.1

Lateral radiograph demonstrating an irreducible posterior simple elbow dislocation

Arthroscopy is not typically performed for simple elbow dislocations, as the pathology needs to be addressed in an open fashion.

29.6 Treatment Options

After physical exam, including documentation of the neurovascular status, and injury radiographs have been obtained, closed reduction should be immediately attempted. Although ideally performed in the operating room, most closed reductions occur in the emergency room. In either setting, the patient should be given IV sedation with a short-acting benzodiazepine and a short-acting narcotic. Sedation allows muscle relaxation, preventing a traumatic reduction [2]. A palpable or audible “clunk” on reduction is a good indicator that the joint will be stable [1].

29.6.1 Reduction Maneuvers

29.6.1.1 Posterior or Posterolateral Dislocations

The patient should be supine with the forearm supinated and elbow in 20–30° of flexion. Supination protects the coronoid from fracture during reduction. Medial or lateral displacement should be corrected first. With an assistant holding countertraction on the upper arm, gentle traction and further flexion should be applied to the forearm to reduce the olecranon distally around the trochlea [2, 7]. The olecranon can be pushed distally to aid the reduction [4]. Hyperextension of the elbow is to be avoided, as this can cause neurovascular entrapment [9].

Reduction can also be attempted in a prone position by extending the elbow with countertraction on the arm, with another hand guiding the coronoid over the trochlea [5].

29.6.1.2 Anterior Dislocation

This is a more difficult reduction, which is better managed in the operating room. After medial or lateral displacement has been corrected, the elbow should be flexed and supinated. With an assistant providing counterpressure on the upper arm, the surgeon should push the forearm posteriorly to bring the olecranon proximally around the trochlea [2].

29.6.1.3 Divergent Dislocations

These injuries are associated with high-energy mechanism and are very unstable. Reduction should be performed in the operating room. The reduction can be performed by reducing the radius and then the ulna to the distal humerus, or the radius and ulna can be reduced and then the forearm reduced to the humerus [4].

After successful reduction, the elbow should be taken through a full range of motion while the patient is still sedated. It is important to note the degree of flexion when the elbow begins to subluxate, as this will be important in post-reduction management. According to Hildebrand, an elbow is stable if it stays reduced from at least 60° of flexion to full flexion [4]. The elbow should also be tested for varus and valgus instability with the elbow in full extension and 30° of flexion, which unlocks the olecranon from the olecranon fossa. Valgus stress is measured with the humerus in full external rotation and a valgus force applied to the forearm, while varus stress is measured with the humerus in internal rotation and a varus force applied to the forearm [7]. Usually the elbow is unstable to a valgus stress [5].

If the elbow is stable to flexion and extension, varus and valgus, the next step is to evaluate the forearm for stability in supination and pronation. With a torn LCL, the elbow is more stable in supination, and an elbow with a torn MCL is more stable in pronation. However, most elbow dislocations involve tears of both the LCL and MCL and therefore should be immobilized in a plaster splint with the forearm in a neutral position and the elbow in 90° of flexion [10].

Theoretically, after reducing a simple elbow dislocation, the joint should retain inherent stability from the contours of the joint surfaces. The elbow should be immobilized for 5–10 days as splinting for more than 3 weeks has been associated with loss of motion [1]. A well-padded posterior plaster splint should be applied with the elbow in 90° of flexion, and forearm rotation in whichever position provides the most stability, usually neutral [4].

Post-reduction radiographs should be performed and evaluated for a concentric joint on both AP and lateral views. If there is a widened joint space, there may be an osteochondral fragment trapped in the joint requiring surgical treatment or there may be persistent instability requiring bracing [1, 7].

Surgical vs. nonoperative treatment depends on the stability of the elbow after reduction. In rare situations open reduction is required in a simple elbow dislocation for irreducible dislocations from entrapped soft tissue or osteochondral fragments [7]. Most elbow dislocations are stable after closed reduction. An elbow that subluxes or dislocates at 45–60° of flexion is unstable and requires surgical intervention as rehabilitation with greater than 60° of extension block is difficult and has a high incidence of flexion contracture. Primary ligament repair in an acute unstable elbow is generally successful because it provides stability to allow early rehabilitation and range of motion.

Recurrent instability in simple elbow dislocations occurs in less than 1–2 % of cases [1]. If an elbow redislocates after reduction and splint immobilization, nonsurgical treatment will most likely fail [10]. An unstable simple elbow dislocation is most likely to have an injured MCL, LCL, and anterior capsule as well as injury to secondary elbow stabilizers with no associated fractures. The amount of soft tissue injury to the flexor-pronator and extensor origins is correlated with the instability of the elbow and likelihood of the elbow to redislocate [1]. McKee et al. evaluated the lateral ligamentous disruption in 61 unstable elbow dislocations and found that 100 % of cases had a LCL and 66 % had concurrent rupture of the common extensor origin [11]. This supports the theory that damage to the secondary stabilizers on the lateral side of the elbow during an acute dislocation results in recurrent instability. Josefsson et al. prospectively compared treatment of simple elbow dislocations by randomizing 30 patients to nonsurgical or surgical treatment with identical postoperative rehab. They found no difference in outcome at 3–7 years in regard to range of motion, grip, and elbow strength. There were no recurrent dislocations or episodes of instability in either group [12].

29.6.2 Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative treatment of simple and stable elbow dislocations includes early splinting or sling for 3–5 days, followed by early range of motion. If the elbow has instability past 60°, a hinged brace with an extension block can be used. Strengthening can begin at 6–8 weeks, but weight through the elbow joint such as pushups and overhead press should be avoided for 3 months [2]. Prolonged immobilization is not recommended, because it can lead to long-term loss of motion [13]. Splinting for more than 3 weeks results in worse patient outcome [14]. Even with early range of motion, patients lose 10–20° of terminal extension [15, 16].

29.6.3 Operative Treatment

For simple unstable elbow dislocations treated in the acute setting, treatment consists of ligament repair. The posterolateral elbow dislocation involves sequential tears of the LCL, anterior capsule, and MCL. For stabilization of these injuries, the LCL should be reconstructed first. After LCL reconstruction, the elbow should be tested for stability. If the elbow is stable through full range of motion, it is not necessary to repair the MCL [17, 18]. Repair of the MCL is not routinely needed for stabilization of an elbow after dislocation. Leaving the MCL unrepaired is advantageous because there is less operative dissection and no need to transpose the ulnar nerve [8].

The patient should be positioned supine with a radiolucent arm table. Standard fluoroscopy via mini-fluoroscopy should be used. If the surgeon would like to use the large C-arm, the image intensifier (larger side) should be used as the operating table.

The incision is made through either a midline posterior approach or a Kocher posterolateral approach. The advantage of a midline posterior approach is that it allows access to the medial elbow if an MCL repair is needed [2].

Kocher approach: Full-thickness skin and subcutaneous flaps are made and elevated laterally. The intermuscular interval is between the anconeus and extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU.) The common extensor origin is often avulsed off the lateral epicondyle (50 % of the time), which helps with the exposure of the LCL. At this point, the torn LCL should be identified. The ligament is usually avulsed from the humeral origin, and there is little tissue left behind from its insertion point on the humerus [11].

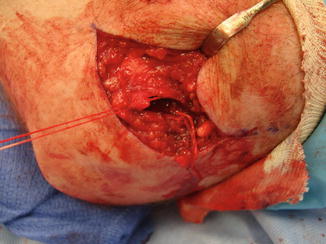

The LCL and the extensor origin should be repaired primarily. This can be done with suture anchors or bone tunnels with #0 or #1 braided nonabsorbable suture. Bone tunnels are created at the humeral and ulnar attachments of the lateral UCL. Isometry should be evaluated to ensure constant tension through full range of motion [7]. In the acute setting, primary repair of the avulsed tendons can usually be performed (Fig. 29.2). However, in the rare case when ligament reconstruction is needed, the palmaris longus can be used as a graft through bone tunnels in the humerus and proximal ulna [2]. If the disruption of the LCL is intrasubstance, then direct repair can be performed with large, braided nonabsorbable sutures [7].

Fig. 29.2

Intraoperative photograph of LCL repair with a suture anchor for fixation of an unstable simple elbow dislocation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree