Fig. 16.1

Patients with internal impingement will complain of pain during the arm cocking and arm acceleration phases of throwing (Reprinted with permission from Digiovine et al. [15])

In contrast to posterosuperior impingement, patients with anterosuperior impingement are slightly older. In a series of sixteen patients with this entity, the average age was 45.3 years [20]. In that series, the majority of patients were not athletes, but rather engaged in manual professions that required regular overhead activity, such as masonry and carpentry. Symptoms are often worsened with overhead movements that involve flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the shoulder. Patients will often note a gradual insidious onset of pain in the anterior aspect of the shoulder and may also note pain in the region of the bicipital groove if associated pathology of long head of the biceps tendon exists. Furthermore, popping, locking, and snapping may occur with unstable labral tears.

A stepwise and systematic physical examination should be performed to assess the lower back, hip, and knee. The clinician may assess functional movements with single leg squats for hip and trunk control, muscle imbalance, and inflexibilities. Examining the patient from the back, scapular winging and muscular atrophy should be noted. The glenohumeral joint line, acromioclavicular joint, the long head of the biceps, and the coracoid process should be evaluated for tenderness. Tenderness over the coracoid process is suggestive of pectoralis minor tendinitis, which can be correlated with scapular dyskinesis [8]. Other signs of scapular dyskinesis include a prominent inferior medial border of the scapula and the appearance of an inferiorly drooped throwing shoulder [35].

Overhead-throwing athletes often display asymmetry between the dominant and nondominant shoulder due to relative muscular hypertrophy of their dominant side. A thorough assessment of range of motion of both shoulders should be performed in both adduction and 90° of abduction. For many years, it has been the general belief that affected shoulder has 10–15° more external rotation at the expense of 10–15° of internal rotation, with the overall arc of motion being comparable to the contralateral side [47]. However, it has recently been demonstrated that patients with symptomatic internal impingement have a decrease in the total arc of motion as well. In a study on collegiate level baseball players, the dominant shoulders had a mean arc of 136.2° compared with 145.8° in the nondominant group, for a side-to-side difference of 9.6°.

While patients with internal impingement often have physiologic laxity, this must be distinguished from pathologic instability. Even without any dislocation or subluxation events, patients may have increased translation that alters their throwing mechanics. The amount of anterior and posterior translation should be noted and compared to the contralateral extremity. The posterior impingement test can also be used to assess for apprehension and pathologic instability. With the patient in the supine position, the shoulder is placed in 90° of abduction, 10° of forward flexion, and maximum external rotation. A positive test is constituted by the reproduction of pain in the posterior aspect of the shoulder. The Jobe’s relocation test is also a useful maneuver to test for internal impingement. The patient is once again placed supine; the arm is brought into 90° of abduction and 10° of forward flexion, and the shoulder is forced anteriorly. With pathologic laxity, patients will report pain with maneuver; however, the pain subsequently subsides with a posteriorly directed force [28].

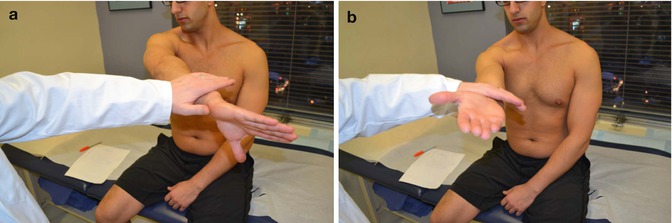

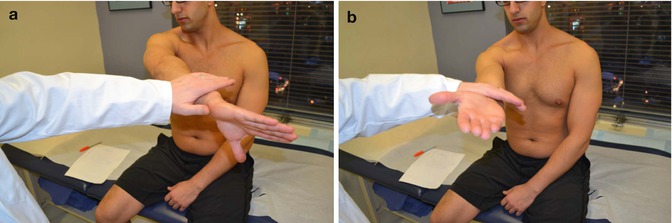

Since internal impingement is often associated with SLAP tears, it must be examined for during the physical examination. To perform O’Brien’s active compression test, the most sensitive and specific exam for SLAP lesions, the patient’s arm is forward elevated to 90°, adducted 15° across the midline, and brought into maximum internal rotation so that the thumb is pointing downward. The patient is told to maintain this position while the examiner stands behind the patient and provides a downward force to the arm. The patient is asked to quantify the amount of pain felt with this maneuver. Subsequently, the patient’s arm is brought into full external rotation while maintaining the other positions of the shoulder. With the palm fully supinated, the examiner once again provides downward pressure which the patient is told to resist (Fig. 16.2a, b). O’Brien’s test is considered positive when then patient notes a significantly greater amount of pain with the arm internally rotated, along with a decrease or resolution of symptoms in full supination. For optimum results, the examiner should not be resisting the patient’s attempt at forward elevating past 90°, but rather the patient should actively resist the clinician’s downward force [49].

Fig. 16.2

(a, b) O’Brien’s Test – the patient’s arm is forward elevated to 90°, adducted 15° across the midline, and brought into maximum internal rotation. The patient is told to maintain this position while the examiner stands behind the patient and provides a downward force to the arm. Subsequently, with the palm fully supinated, the examiner once again provides downward pressure. The test is considered positive when then patient notes a significantly greater amount of pain with the arm in pronation and relief of pain with supination

16.4 Essential Radiology

Radiographic evaluation begins with a standard shoulder series, including the anteroposterior, axillary, and outlet views to assess for overall alignment and geography. Specific for internal impingement, Bennett and colleagues described an exostosis of the posteroinferior glenoid rim secondary to repetitive triceps traction in baseball players and coined it the Bennett lesion [3]. The greater tuberosity must also be examined for sclerotic and cystic changes, as these are found in nearly half of pitchers with internal impingement [66]. Furthermore, rounding or remodeling of the posterior glenoid rim may also be noted.

Magnetic resonance imaging is the most utilized imaging modality to diagnose pathologic conditions of the shoulder. Of note, many asymptomatic patients may also have positive MRI findings; it is therefore imperative to compare radiographic findings to the physical examination. MRI has an advantage over even arthroscopy in that in can not only detect articular or bursal-sided rotator cuff tears but also diagnose intrasubstance degeneration, which may be difficult to directly visualize. Articular-sided rotator cuff tears are often found in patients with internal impingement. In fact, up to 40 % of professional baseball pitchers have completely asymptomatic partial articular-sided supraspinatus tendon avulsion (PASTA) lesions [12]. Furthermore, MRI can also be enhanced with gadolinium contrast to increase the diagnostic value; it has sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for diagnosing labral tears of approximately 90 % [16] (Fig. 16.3). Some experts have recommended performed magnetic resonance imaging with the shoulder in both the abducted and abducted and externally rotated position. A recent study showed that these sequences appear to improve the diagnostic accuracy of soft tissue anterior and posterior labral tears, SLAP tears, and significant bony glenoid lesions [45].

Fig. 16.3

Coronal oblique image of MRI arthrogram showing a superior labral tear (white arrow) with dye tracking into the space between glenoid and labrum and a partial-thickness rotator cuff tear (red arrow)

The most common constellation of MRI findings in patients with internal impingement includes undersurface tears of the supraspinatus or infraspinatus tendon and cystic changes in the posterior aspect of the humeral head associated with posterosuperior labral pathology [21]. Additional findings may include mature periosteal bone formation at the posterior aspect of the capsule (Bennett lesion) and posterior capsular contracture at the level of the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex [17]. There may also be remodeling of the glenoid with narrowing of the spinoglenoid notch from chronic pressure transmitted to the posterosuperior aspect of the glenoid from the shoulder being placed in repetitive abduction and external rotation.

16.5 Disease-Specific Clinical and Arthroscopic Pathology

Prior to a diagnostic arthroscopy, a thorough examination under anesthesia is performed to obtain a true assessment of the patient’s range of motion and laxity. The clinician should record the patient’s forward elevation, external rotation at neutral and 90° of abduction, and internal rotation. The shoulder should also be examined for the degree of anterior and posterior translation. Grade 1 represents mild translation, grade 2 is translation to the glenoid rim, grade 3 translation causes a dislocation that spontaneously reduces, and grade 4 is a fixed dislocation. Both range of motion and degree of translation should be compared to the contralateral extremity.

A comprehensive diagnostic arthroscopy is performed visualizing the entirety of the joint with a probe. Depending on the nature of the expected pathology, the patient is placed into the beach chair position for the rotator cuff or the lateral decubitus position for labral work and capsular laxity. Two portals are typically used, the posterior and rotator interval portal, with further portals dependent on the visualized pathology. Arthroscopic evaluation begins with examination of the glenoid and humeral head for chondral wear. The superior glenoid is then evaluated for SLAP lesions; viewing from both anterior and posterior is mandatory to fully appreciate these lesions. The glenoid articular cartilage generally extends medially over the superior corner of the glenoid; absence of cartilage in this area indicates labral detachment. The arthroscopic peel back was described by Burkhart and colleagues. With the arm placed in the throwing position, in the presence of a tear, the labrum will peel away from the glenoid [6]. The biceps tendon is next evaluated from its insertion on the supraglenoid tubercle distally toward the intertubercular groove. A probe is used to pull the tendon into the joint which allows for circumferential examination for tendinosis or synovitis, as well as to test for the stability of the biceps anchor.

Following inspection of the biceps, the superior and anterior labrum is evaluated from 12 to 6 o’clock, assessing for the integrity of the anterior glenohumeral ligaments as well as the degree of capsular laxity or tears. The subscapularis should also be examined for tearing as anterosuperior impingement can cause undersurface tears. Next, examination of the axillary pouch is performed, assessing the volume of the pouch and viewing for synovitis or hemosiderin deposits. From the axillary pouch, visualization proceeds posteriorly where the posterior labrum can be assessed. However, visualization of this area can be enhanced by placing the arthroscope in the anterior portal.

The rotator cuff should then be inspected, with particular attention given to the undersurface of the cuff at the junction between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. Viewing from posterior, the arm may be brought into 90° of abduction and full external rotation to assess for abnormal impingement between the rotator cuff and posterosuperior labrum. Lastly, the subacromial space should be examined for bursitis and evidence of external impingement, such as fraying or ossification of the coracoacromial ligament.

16.6 Management of Internal Impingement

Following a physical examination and appropriate imaging of the affected shoulder, the clinician can make recommendations for treatment. Both nonoperative and operative treatment may be recommended by the treating provider based on several principles. The clinical evaluation must correspond with imaging to make the diagnosis of internal impingement. The diagnosis of internal impingement without supporting physical exam findings or radiographic confirmation is unlikely to have fruitful recovery following an undirected course of therapy or arthroscopy. The level of function of the athlete is an important consideration when making a choice as well. The time frame of return to sport can inform the provider to make certain recommendations as well as the length of time necessary for expected recovery from both nonoperative management and in the postoperative course. Lastly, other pathological states including rotator cuff tears, SLAP tears, or labral tears should be evaluated and treatment of these conditions should be considered as corresponding diagnoses with different treatment options and recovery time frames.

16.6.1 Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative treatment should always be the first line of treatment for patients with internal impingement of the shoulder. Athletes with internal impingement should be notified that the majority of patients improve with cessation of throwing activities and focused therapy modalities. Patients with new-onset impingement symptoms should be initially treated with throwing modification, initiation of routine NSAID use, and enrollment into a formal throwing therapy program. Attenuation of throwing activity can be an initial period of 2–3 weeks to allow for the initial phase of inflammation to subside while using NSAIDs and undergoing a focused regimen of thrower-specific therapy.

A focused throwing regimen should contain three key components: application of kinetic chain exercises, shoulder mobility, and shoulder strengthening [33]. The authors recommend a complete therapy regimen that focused on these three principles in an effort to maximize treatment outcomes.

Kinetic chain exercises are initiated with the primary reason of making the throwing motion a more dynamic and mechanically sound action. These exercises focus on proximal core strengthening, hip mobility and strengthening, and leg drive and strength. It is known that about 50 % of throwing velocity comes from step and rotation of the trunk [57]. It is important to have flexibility and a fluid kinetic chain of motion allowing for transfer of energy from the lower extremity and core muscles to the throwing arm. In an effort to encourage muscular training and control during the kinetic chain, therapy should focus on core and lower extremity flexibility, balance, and strength.

Keys behind shoulder mobility include scapular stabilization, restoring normal external and internal rotation deficits, and addressing any mechanical or dynamic restraints within the spine and shoulder. Muscle balance and symmetry is the goal behind this second key principle of rehabilitation in the throwing shoulder [33]. However, before symmetrical and mechanically sound kinematics may be restored, any pathological motion must be minimized. This is done through selective stretching. Selective stretching has not only been found to alleviate impingement as well as rotation deficits, it also has been noted to be protective from future injury [54, 63].

Contractures of posterior capsule, posterior rotator cuff, pectoralis minor, and the short head of the biceps can lead to glenohumeral internal rotation deficit. Several different exercises have focused on improving compliance of posteroinferior contracture through selective stretching. The cross-body stretch was described by McClure et al. as an exercise that was shown to increase internal rotation of the affected side when compared to the contralateral side [40]. An additional exercise is the sleeper stretch which has further been shown to be effective in stretching the posterior contractures as well as pectoralis minor which has additionally been implicated in pathological scapular motion [36]. The pectoralis minor may also be stretched by placing a rolled towel between the athlete’s shoulder blades while supine and applying a posterior directed force on the shoulder. Two additional stretches include the internal rotation stretch and the horizontal adduction stretch. The internal rotation stretch involves the arm being placed in the throwing (cocked) position. The arm is then internally rotated to stretch the posterior rotator cuff. The horizontal adduction stretch may be done with the arm horizontally adducted while the scapula is stabilized.

All of these stretches have a goal of minimizing internal rotation deficit to within 18° (range 13–20°) compared to the contralateral side [64]. In an article by Tyler et al., the authors noted the clinical outcomes of a stretching program on symptomatic throwers [58]. In that article, the authors found that there was a greater improvement in posterior shoulder tightness in those patients with complete resolution of symptoms compared to patients with residual symptoms (35° vs 18°). The authors further noted that improvements in glenohumeral internal rotation deficit and external rotation loss were not different between patients with and without residual symptoms of pain.

The last tenet of nonoperative treatment of internal impingement of the shoulder is shoulder-specific strengthening through restoration of scapular motor control, initiation of a scapular feedback program, and promotion of eccentric control of the shoulder and elbow through an increased number of repetition throwing cycles. Several authors have pointed out that function in the throwing shoulder is heavily dependent on scapular muscle strength, endurance, and also neuromuscular control [31]. Specific exercises focusing on these principles often beginning with closed chain exercises progressing to open chain scapular muscle training.

As an impingement that occurs later in the throwing shoulder pathological process, anterior impingement remains a described yet mostly unknown entity. It is understood that anterosuperior impingement is likely due to chronic micro-instability of the anterior capsulolabral structures with injury to the deep portion of the capsule and subscapularis tendon. This impingement is thought to occur during the follow-through phase of throwing. Although there is not a specific regimen for therapy for anterosuperior impingement, the same neuromuscular control and muscle recruitment for a mechanically balanced shoulder may be assumed to be of benefit. Furthermore, emphasis on proper throwing mechanics with kinetic chain exercises can teach proper muscular control from the wind up to the follow-through of the pitch.

After initiation of the initial phases of therapy, more advanced phases are undertaken with a goal of increasing power and endurance and a gradual reintroduction of throwing activities. The various portions of therapy have been described in phases with phase 1, the acute phase, focusing on scapular and glenohumeral control and activation [33]. Phase 2 is focused on core exercises, the kinetic chain, and isotonic strengthening. This is the recovery phase. The last phase, the functional phase, involves reintroduction of throwing with emphasis on control, velocity, and endurance. This last portion of therapy may prove to be the most problematic as the reintroduction of throwing activities is very dependent on patient response to pain. Such an interval throwing program requires that the throwing athlete remain asymptomatic before advancement of the throwing to normal velocity and number of throws performed. The expectation is that the patient be able to return to full throwing velocity over 3 months time. If the patient fails to meet this criterion in a 3–6-month range and cannot perform at a level necessary for competition, then the patient is considered for surgical intervention.

There is a certain subset of patients that can be appropriately treated with nonoperative management after the diagnosis of internal impingement is made. It is the responsibility of the provider to be able to recognize those patients who would make the most significant gains after a directed course of physical training and therapy. Several features elicited in the physical examination have been found to predict success with nonoperative management [32]. Those factors include pain with resisted abduction, pain with forward flexion, and the positioning of the scapula prior to therapy. These authors further found that sustained rotator cuff strength at 90° of abduction was predictive of success in those patients not having surgery.

16.6.2 Operative Treatment

Operative treatment of internal impingement is focused on sites of pathology as identified by physical examination and advanced imaging. Because internal impingement represents a spectrum of injury, the orthopedic provider must be willing to address multiple sites of injury including the anterior and posterior labrum, the superior labrum, the biceps tendon, the capsule, and the rotator cuff specifically the supraspinatus and anterior portion of the infraspinatus. Jobe has offered that there are five main anatomical sites of pathology: the posterosuperior labrum, the articular portion of the rotator cuff, the greater tuberosity, the inferior glenohumeral ligament, and the posterosuperior glenoid [29]. Treatment of these sites of injury is focused on restoring the kinematics and anatomy necessary for a functioning high-level throwing athlete. Although surgical repair cannot make the anatomy “normal,” it can remove sites of physical aberration and provide a more structurally sound labral and rotator cuff complex.

16.6.2.1 Operative Treatment of Labral Pathology Associated with Internal Impingement

The labrum serves many purposes in the shoulder and does more than simply provide a mechanical bumper for stability. This fact has been noted in that with labral resection, the amount of glenohumeral translation increases only approximately 10–20 % [37]. It has been noted to enhance the concavity/compression mechanics of the glenohumeral joint; serve as a site for attachment for the biceps, glenohumeral ligaments, and capsule; and lastly serve as a proprioceptive feedback sensor [50, 59]. Surgical intervention should be focused on restoring these key characteristics of the labrum by enhancing stability of the labral tissue without restricting the compliance of the soft tissue.

Surgical intervention of the labrum begins with an arthroscopic evaluation and mechanically testing the labrum under direct visualization. The surgeon will need to view the labrum attachment to the glenoid and will need to pay specific attention to the superior labral attachment in the SLAP region. Diagnosis and treatment are based primarily on arthroscopic evaluation of the SLAP region [44]. There is some difficulty in diagnosing a true type II SLAP tear as a separate entity from one of the many normal anatomic variant in the patient undergoing surgery. Normal variants in the superior and anterior labrum include sublabral foramen, a Buford complex with a cord-like MGHL, and discoid variant superior labral tissue. There is great variation in the anterior superior labrum and the presence of a cord-like middle glenohumeral ligament is more often seen in isolation than combined with a deficient anterior labrum [26]. The quality of the labral tissue, amount of inflammation around the labrum, and the amount of exposed glenoid can be assessed and used to direct a surgical decision. Performing dynamic testing to recreate the “peel-back” mechanism can further demonstrate loss of labral integrity [6]. The “peel-back” maneuver is done by placing the arm in a throwing position with external rotation and abduction of the shoulder. The labrum is seen to “peel back” from the posterosuperior glenoid in a positive test. The arthroscopic evaluation will also need to focus on the amount of chondral injury more specifically examining cartilage damage on the superior rim of the glenoid as a sign for an acute SLAP injury [53]. Further chrondral damage may be assessed in the case of instability and early degenerative changes. The glenohumeral ligaments and capsular attachments will also need to be examined by viewing the capacious nature of the joint as demonstrated through a “drive-through sign.” Insufficiency of the glenohumeral ligaments can also be noted through dynamic abduction and rotation testing under visualization. The posterior labrum and posterior capsular tissue will also need to be noted for any adhesions or decreased compliance as noted in the GIRD phenomenon [9].

16.6.2.2 Operative Treatment of Rotator Cuff Injury Associated with Internal Impingement

Rotator cuff injuries are included in the pathological process of internal impingement. The rotator cuff tears that are found are almost always partial undersurface tears that are approximately 2–5 mm from the actual insertion site [32] (Fig. 16.4). This undersurface tearing may in fact be a normal result of the throwing motion in high-level athletes which has been noted to be present in 40 % of asymptomatic pitchers [12]. In symptomatic patients, a partial-thickness tear of the articular side of the rotator cuff was noted in 80 % of professional overhead athletes with a diagnosis of internal impingement [51]. The proposed mechanism for these partial-sided rotator cuff tears is significant horizontal abduction with increased contact stresses at the posterior cuff/labral interface that is a result of compensatory external rotation in throwers. The typical appearance of these impingement-type rotator cuff tears is fraying in the infraspinatus that does not extend into the medial tendon. If there is delamination that extends medially into the supraspinatus or the infraspinatus tendon, several authors have recommended transtendinous repair [25]. Furthermore, many authors agree that if there is greater than 50 % involvement of the insertion, results tend to be less reliable with just a simple debridement of partial articular-sided tear. This has led several authors to propose stabilization of impingement-type tears if they are greater than 50 % of the width of the insertion [65]. Conway et al. examined 14 baseball pitchers with an average age of 16 who were treated with a repair of intratendinous rotator cuff tears and concurrent pathology including labral tears and SLAP tears [13]. They found that 89 % percent of patients undergoing intratendinous repair were able to return at the same or higher level at 16-month follow-up. An additional study by Ide et al. reported the results of an arthroscopic transtendon repair in patients with >6 mm partial-thickness articular-sided tears of the supraspinatus tendon [27]. The authors found good to excellent results in 16/17 patients. However, of six overhead-throwing athletes, only two were able to return to their previous sport at the same level. Many techniques for repair have been recommended including transtendinous reattachment of the tendon to bone using bone tunnels as well as anchors [43]. Although there is no evidence that one fixation technique is more mechanically sound than the others, the surgeon will need to use proper rotator cuff repair techniques to ensure firm fixation. Some authors also recommend completion of the partial-thickness tear in an effort to perform a more formal repair technique. [39] The authors recommend completion of the tear only if there is a greater than 75 % involvement of the insertion site.