43 The Skin and Rheumatic Diseases

Psoriasis

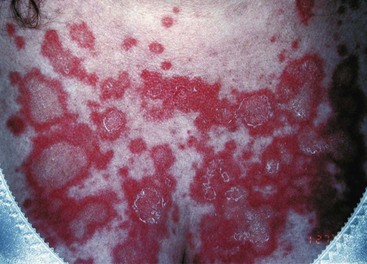

General phenotypes of psoriasis are chronic plaque, guttate, localized pustular, generalized pustular, and erythroderma.1 Chronic plaque and guttate psoriasis are the most common, and generalized pustular psoriasis and erythroderma typically the most disabling and even life threatening. Chronic plaque psoriasis lesions are often relatively large in diameter and occur preferentially on elbows, knees, scalp, genitalia, lower back, and the gluteal cleft, although they may occur at many other locations. It is quite common for only one area of skin such as the scalp to be affected. Guttate lesions are relatively small in diameter and usually quite numerous, distributed preferentially on the trunk and proximal extremities (Figure 43-1). Guttate psoriasis occurs relatively commonly in children and young adults, often manifesting a few weeks after a streptococcal infection.

Figure 43-1 Guttate psoriasis resembles “drops” of discrete scaly papules with erythema, often on the trunk.

(Courtesy Dr. Nicole Rogers, Tulane University Department of Dermatology, New Orleans.)

Nail changes are common, occurring in about half of patients, and are often mistaken for fungal infection. Specific changes include pitting, onycholysis (“oil spots”), dystrophy of nails, and loss of the nail plate. These changes are not specific for psoriasis. Notably, pitting may occur as a result of trauma, and the finding of a few pits in the nails may not be helpful diagnostically. Nail changes are more frequent in patients with arthritis of the distal interphalangeal joints.2

Common topical therapies include corticosteroids, tar, anthralin, calcipotriene, and tazarotene.3 Phototherapy using sunlight, broadband ultraviolet B (UVB), narrowband UVB, or psoralen ultraviolet A-range (PUVA) is still a mainstay of therapy for many patients. Common systemic therapies include methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, and the relatively new biologic agents such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab. Cyclosporine may be useful to attain relatively rapid control of severe psoriasis, but it is less often used as a long-term therapy. Although topical corticosteroids are an acceptable treatment for many patients, systemic corticosteroids are avoided for the treatment of cutaneous disease, in particular due to the observation of severe flaring of psoriasis following withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids.

Reactive Arthritis

The diagnosis of reactive arthritis may be rather straightforward in a young male who develops urethritis, conjunctivitis, and arthritis following an episode of nongonococcal urethritis. However, in many cases the clinical features are not fully expressed and cutaneous lesions may be helpful in establishing the diagnosis.4

The palms and, particularly, the soles may develop lesions that are initially similar to the small erythematous papules and pustules of the genital region. With time, these lesions, termed keratoderma blenorrhagica, tend to become markedly hyperkeratotic (Figure 43-2). They may coalesce into large plaques or generalized hyperkeratosis involving the entire plantar surface, or they may remain discrete, erythematous, hyperkeratotic papules a few millimeters in diameter.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of RA.5 They occur more often in seropositive patients and correlate somewhat with higher rheumatoid factor titers, more severe arthritis, and increased risk for vasculitis. Nodules are usually relatively deep, firm, and painless and tend to develop over areas of pressure and trauma such as the extensor forearms, fingers, olecranon processes, ischial tuberosities, sacrum, knees, heels, and posterior scalp (Figure 43-3). In patients who wear glasses, nodules may develop under the bridge or nosepieces. In most cases, rheumatoid nodules are in the subcutaneous tissue and/or deep dermis, but occasionally they may occur more deeply or more superficially.

The term rheumatoid nodulosis has been used to describe an entity characterized by subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules, cystic bone lesions, rheumatoid factor positivity, and arthralgias in patients with little or no evidence of systemic manifestations of RA or erosive joint disease.6 Older males are preferentially affected.

The development of nodules in RA patients undergoing treatment with methotrexate has been noted by several observers and termed accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis.7 The nodules are newly appearing and occur preferentially on the hands. There are also case reports of the phenomenon in RA patients treated with etanercept.

The other major type of cutaneous lesion associated with RA is neutrophil predominant. Rheumatoid vasculitis occurs more frequently in patients who are seropositive and have rheumatoid nodules, and it often occurs relatively late in the course of the disease.8 Vessels of any size may be affected. In the skin, vasculitis may appear as purpuric papules and macules, nodules, ulcerations, or infarcts. Bywaters’ lesions are periungual or digital pulp purpuric papules representing a small vessel vasculitis, but not necessarily associated with vasculitic lesions elsewhere.

The term rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis has been given to describe chronic, erythematous, urticarial-like plaques that occur primarily on the distal arms.9 Clinically and histologically, rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis is similar to Sweet’s syndrome and may be a variant of it.

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) of connective tissue disease is an unusual condition or set of conditions for which consistent terminology is still evolving. As the name implies, the major bases for diagnosis of this entity are the histologic appearance and the occurrence in a patient with connective tissue disease, often RA.10 The clinical appearance ranges from erythematous or flesh-colored papules that appear primarily on fingers and elbows to erythematous or flesh-colored linear cords on the trunk. Some authors classify the latter as interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with cutaneous cords or interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with arthritis (IGDA). Treatment of PNGD and IGDA can be challenging. PNGD may respond to dapsone or sulfapyridine. IGDA can be treated with antimalarials or immunosuppressives, but because this is both a newly described and relatively infrequent condition, all evidence is based on case reports and small case series. Patients can progress to a severe deforming arthritis. In some cases, granuloma annulare and rheumatoid nodule may be in the differential diagnosis.

Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis/Still’s Disease

The majority of patients with classic Still’s disease manifest an exanthematous eruption coincident with daily fever spikes.11 The lesions are evanescent, usually nonpruritic, erythematous macules occurring over the trunk, extremities, and face. The differential diagnosis includes viral exanthem, drug eruption, familial periodic fever syndromes, and rheumatic fever. It is not unusual for exanthems of any type to be more prominent during fevers, but it is not expected that viral exanthems and drug eruptions clear completely between fever spikes. However, it should be noted that the eruption of erythema infectiosum (fifth disease) due to parvovirus B19 may resolve completely but reappear when the skin temperature rises, as with warm baths or exercise. Adult-onset Still’s disease is also typified by an evanescent erythematous, sometimes salmon-colored eruption over the trunk and extremities, associated with high fever. Skin biopsy may be nonspecific. However, there has been a report of a unique histologic pattern consisting of dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the upper epidermis along with increased dermal mucin in adult-onset Still’s disease.12 The frequency with which this histologic pattern is present in Still’s disease remains to be determined.

Lupus Erythematosus

Lupus-Specific Skin Lesions

James Gilliam classified cutaneous lesions as being specific or nonspecific for lupus, discoid lupus lesions being an example of the former and palpable purpura being an example of the latter.13 Although this division of lesions is useful, sometimes a lupus-specific lesion occurs in a patient whose primary autoimmune disease is something other than LE. For example, SCLE lesions may occur in patients whose primary condition is Sjögren’s syndrome, and discoid lesions may be seen in a variety of conditions such as mixed connective tissue disease. Many of the lupus-specific skin lesions can occur in patients who have no evidence of extracutaneous disease.

Acute cutaneous lupus (ACLE) lesions are typified by malar erythema, the classic butterfly rash (Figure 43-4). The inflammation tends to be superficial, with little propensity to scar. Precipitation or exacerbation of lesions by sun exposure is common, and lesions tend to be distributed on the sun-exposed face, neck, extensor arms, and dorsal hands, where the skin over the knuckles is relatively spared. Often the lesions are quite transient, but they may be persistent. When the face is severely affected, facial edema may be prominent. Oral lesions are often present concurrently. Acute eruptions with considerable focal basal cell damage can result in erythematous papules with dusky centers that clinically mimic erythema multiforme. The major importance of recognition of ACLE is its strong association with systemic disease. The differential diagnosis of malar rash may include several conditions. In some cases, the facial rash of ACLE may be difficult to distinguish from rosacea. Seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and photosensitive eruptions such as polymorphous light eruption and drug-induced photosensitivity may also be considered. Dermatomyositis may cause a photosensitive facial erythema with edema similar to ACLE, although the erythema tends to be more violaceous. Persistent lesions on the neck and arms may be indistinguishable from SCLE. Discoid lupus lesions occasionally appear in a butterfly distribution, where they can result in disfiguring scarring. Skin biopsy is usually not performed on malar erythema because of its transient character, the scar resulting from biopsy, and the availability of other means of establishing the diagnosis of SLE. If a biopsy is done, it should be noted that dermatomyositis and SCLE cannot be distinguished from ACLE by histology and also that skin biopsy findings are sometimes nonspecific.

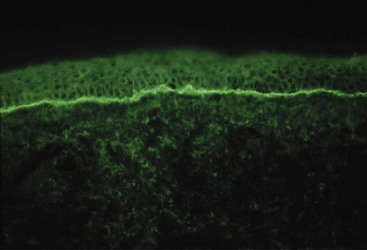

SCLE is a photosensitive eruption usually associated with anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies.14 Lesional morphology is of two main types, annular erythematous plaques and scaly erythematous psoriatic plaques. Lesions are distributed over sun-exposed skin of the arms, upper trunk, neck, and sides of the face (Figure 43-5). Inexplicably, the midfacial area is usually uninvolved. Fair-skinned individuals are preferentially affected. Lesions may resolve with hypopigmentation or even depigmentation, but they rarely scar. Several drugs, particularly hydrochlorothiazide, have been reported to induce SCLE.15 The risk for development of systemic disease is not fully known, but perhaps 15% or so of patients with SCLE have or will develop significant systemic disease, often SLE, Sjögren’s syndrome, or an overlap. Depending on the morphology of the lesions and the clinical presentation, the differential diagnosis may include psoriasis, tinea, polymorphous light eruption, reactive erythema, and erythema multiforme. Skin biopsy for routine histology is often helpful in establishing the diagnosis. The characteristic finding of skin biopsy for immunofluorescence is a particulate deposition of immunoglobulin G (IgG) in the epidermis (Figure 43-6) both in lesions and uninvolved skin.16 This pattern can be reproduced in animal models by infusing anti-Ro, and thus immunofluorescence results provide information that duplicates serologic testing for anti-Ro.17 The particulate epidermal pattern seen in normal skin does not carry the same implication for increased risk of having SLE, as does the finding of granular deposits of IgG at the dermal-epidermal junction (the nonlesional lupus band test). It should be noted that many immunofluorescence laboratories do not routinely report epidermal findings.

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) lesions are the most common of the persistent lupus-specific skin lesions. Active lesions are erythematous papules and plaques that feel indurated to palpation because of the substantial numbers of inflammatory cells infiltrating the dermis. Involvement of hair follicles may be grossly evident as follicular plugs and scarring alopecia. Dyspigmentation is common, often with hypopigmentation or even depigmentation in the center and hyperpigmentation at the periphery (Figure 43-7). Visible scale is common and occasionally is pronounced in a clinical variant called hypertrophic DLE. In established lesions, scarring may be disfiguring. Lesions tend to occur on the scalp, ears, and face but may be widespread and occasionally involve mucosal surfaces. It is unusual to have lesions below the neck in the absence of lesions above the neck.18 Sun exposure may exacerbate DLE in some cases, but the presence of lesions in sun-protected areas of the scalp and ears and the frequent absence of a history of photosensitivity indicates that sun exposure is probably not a trigger in every instance. There are case reports of squamous cell carcinoma developing in established DLE lesions. In a patient who presents with DLE lesions, the risk for developing SLE is probably about 5% to 10%, although mild systemic symptoms such as arthralgias are relatively common. The differential diagnosis of DLE lesions is often that of conditions exhibiting intense lymphocytic or granulomatous infiltrates such as sarcoid, Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate, granuloma faciale, polymorphous light eruption, lymphocytoma cutis, and lymphoma cutis. In the scalp, lichen planopilaris and other scarring alopecias may be considered. Skin biopsy for routine histology often establishes the diagnosis definitively. In more difficult cases, biopsy for immunofluorescence may provide additional supporting diagnostic information. Lesions are expected to have granular deposits of immunoglobulins at the dermal-epidermal junction. Unless there is concomitant systemic disease, normal skin is expected not to have immunoglobulin deposits.

Figure 43-7 Discoid lupus erythematosus of the scalp, with scarring alopecia and central hypopigmentation.

(Courtesy Dr. Nicole Rogers, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans.)

Tumid lupus (TLE) skin lesions are similar to DLE lesions in that they are erythematous indurated papules and plaques with a substantial lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike DLE, though, the lesions do not exhibit epidermal abnormalities, follicular involvement, or scarring. Considerable mucin is present in the dermis, giving the lesions a somewhat boggy look and feel. In some reports, lesions are most common on the face and may be reproduced by phototesting.19 The risk for SLE appears to be low, and immunoglobulin deposits are not generally present in skin biopsies. Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate and other lymphocytic and granulomatous infiltrative conditions (see earlier) are in the differential diagnosis. Skin biopsy for routine histology is valuable in establishing the diagnosis, with the exception of reliably distinguishing TLE from Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate. Some have argued that Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate and TLE are one and the same, and it might reasonably be argued that what is called TLE is not appropriately classed as a form of chronic cutaneous LE but rather as an independent entity. However, the presence of TLE lesions in some patients with lupus is evidence to the contrary.

Lupus panniculitis (LEP) lesions have inflammation in the subcutaneous tissue, resulting in deep indurated plaques that become disfiguring, depressed areas (Figure 43-8). Usual sites of involvement are face, upper trunk, breasts, upper arms, buttocks, and thighs. The risk for SLE is not known precisely, but clearly some patients with LEP have or will develop SLE. The differential diagnosis is that of the panniculitides, but the distribution exhibited in LEP is unusual for most other conditions that cause panniculitis. The combination of clinical presentation and skin biopsy for histology usually serves to establish the diagnosis.

Treatment of the lupus-specific lesions is relatively similar for most of the subtypes, with some exceptions and modifications. Sun protection is critical for lesions that are initiated or exacerbated by sun exposure. Many or most patients underestimate the amount of sunscreen needed to apply, the potential damage of the seemingly minimal exposure one has in the course of day-to-day activities, and the value of protective clothing. Topical therapy is often used to avoid side effects of systemic medications or to provide adjunctive therapy, although topical agents are unlikely to be beneficial if the disease process is deep, as in panniculitis. Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the most often used local therapy, but there are some reports of benefit from topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical retinoids.20,21 The first-line systemic medication for cutaneous lupus is antimalarial therapy. Several reports indicate that smoking tobacco decreases the likelihood of response to antimalarials.22 For antimalarial-resistant skin disease, a wide variety of medications have been used but there is no clear second choice when antimalarials have not worked. Although dapsone is arguably not helpful in most types of cutaneous lupus, it may be helpful in neutrophil-predominant bullous eruptions.23 Measures to keep the skin warm may be useful for chilblains lupus.

Nonspecific Cutaneous Lesions

A wide variety of lupus nonspecific skin lesions has been reported. Many of these such as vasculitic lesions are cutaneous clues to the possibility of extracutaneous disease. Noteworthy in this regard is livedo reticularis. The netlike erythema of livedo reticularis is a vascular phenomenon due to lowered oxygenation at the periphery of the area supplied by a particular vessel. This can simply be due to vasoconstriction, such as occurs in a cold environment, and thus can be a benign finding. If livedo is more prominent than usual, not corrected by warming, and persistent, it can indicate lowered flow due to pathology such as vasculitis, atherosclerotic disease, or sludging. In lupus, livedo reticularis may be a sign of the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.24

Neonatal Lupus Syndrome

Neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) is associated with maternal IgG autoantibodies to Ro/SSA and La/SSB.25 Affected children may have cutaneous lesions, cardiac disease (notably complete heart block and/or cardiomyopathy), hepatobiliary disease, or hematologic cytopenias. Most children have only one or two features of the disease. Similar to the anti-Ro/SSA-associated SCLE of adults, the skin lesions are often photosensitive, have relatively superficial inflammatory infiltrates, and do not tend to scar. The lesions usually appear at a few weeks of age but have been noted at birth in several cases. The natural history of the skin disease is that the lesions last for weeks or months and resolve spontaneously, usually leaving no residuum. In a few cases, persistent telangiectasias have been noted. Individual lesions appear as erythematous annular papules or plaques. Lesions are usually more numerous and more intensely inflamed on the face and scalp but may additionally occur on the trunk and extremities. Confluent periorbital erythema, giving the appearance of an erythematous mask, is common and diagnostically helpful. Even though the skin disease resolves and most children without extracutaneous involvement remain otherwise healthy, there is a possibility that children who have had NLE are at increased risk for the development of autoimmune disease later in childhood.26