The orthogeriatric team approach to the management of the elderly

Different models of care for hip fractures

History of the Rochester Model of Care

History of lean business principles

Standardized care according to the Rochester Model

Implementing a Rochester-style program

INTRODUCTION

Hip fractures are a serious public health issue worldwide. There are an estimated 330,000 hip fractures annually in the United States.1 Age is a major risk factor, with those over the age of 85 at greatest risk for hip fractures.2 Since this age group is the fastest growing segment of the population,3 the incidence of these injuries will assuredly increase in the coming decades.

Not only are hip fractures common, but these injuries carry with them a high incidence of complications, with studies consistently reporting a 3% inpatient mortality and a 21–23% 1-year mortality.1,4,5 For those who survive the initial treatment, long-term disability is common. Half of these patients fail to regain their prefracture level of mobility,6 and 25% of those who lived independently will require long-term nursing home care.7

Elderly hip fracture patients often have several comorbid conditions which affect the outcome of care. While almost all hip fractures require surgical treatment, medical physicians are most able to manage the patient’s comorbid medical conditions. Geriatricians are expert at caring for medically complex hip fracture patients.8 Aside from medical problems, geriatricians are skilled in dealing with polypharmacy, where more than six to nine different medications have been prescribed to a patient. Polypharmacy is common in the elderly hip fracture population.9 Polypharmacy usually causes drug–drug interactions that can further affect geriatric hip fracture patients in the perioperative period and in the long term.

DIFFERENT MODELS OF CARE FOR HIP FRACTURES

There are five different models of care for hip fractures, which have been summarized well by Giusti et al.10 These include the traditional model, consultant team, interdisciplinary care/clinical pathway model, geriatric-led fracture service and geriatric co-managed care.

Under the traditional model, a patient is admitted to an orthopaedic ward with an orthopaedic surgeon assuming responsibility for care. Questions regarding medical issues and complications are managed by consultant services. Different physicians might end up managing the patient during the inpatient stay. Early rehabilitation takes place on the orthopaedic ward with a hospitalization lasting up to 2 weeks. At discharge, the patient is transferred home, to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) or acute rehabilitation facility without substantial continuity of care. The discharge timing and destination heavily depend on the medical system and country in which the patient is treated.10

A consultant team model is a variation of the traditional model, in which a patient is admitted to the orthopaedic surgery service but with a medical consulting service regularly seeing the patient, frequently during the postoperative phase of care.

With interdisciplinary care/clinical pathway models, there are some differences in how the models are described. However, the defining aspect of this type of care is the absence of ‘single true leadership’ in the management of patients.10 Additionally, several different healthcare professionals with different patient care duties are involved in patient care.

A geriatrician-led fracture service with an orthopaedic consultant has been described in which the patient is admitted to the geriatrics service. The admitting geriatrician coordinates timing of surgery, procedures, diagnostic testing, treatments and discharge planning.10 Meanwhile, the orthopaedic surgeon is a consulting physician who performs surgery and follows the patient intermittently until complete wound healing.

In the co-management model for hip fracture, also known as the Rochester Model of Care, the patient is technically admitted to the orthopaedic surgery service but co-managed by both orthopaedics and geriatrics, meaning that the patient is seen by both teams every day. This chapter will focus on the Rochester Model of co-management developed to treat hip fracture patients.

ORTHOGERIATRIC CO-MANAGEMENT

Given the multiple comorbidities and propensity for poor outcomes in geriatric hip fracture patients, the involvement of geriatricians is desirable to assist with medical management. This type of care is referred to as orthogeriatric co-management and was first used in the United Kingdom during the 1950s but not widely adopted in the United States until recently.11 Studies have demonstrated that co-management reduces in-hospital complications,12,13 decreases the length of hospital stay,14,15,16 and 17 reduces readmission rates,13 lowers mortality,12,13,18,19,20 and 21 lowers costs,15 requires lower levels of care at discharge15,20 and results in better function postoperatively.22 Orthogeriatric co-management results in better satisfaction for patients and providers alike.18 Orthogeriatric co-management has also rarely been described in the United States.23,24 and 25 These factors led to the development of a comprehensive program combining orthogeriatric co-management with lean business principles to provide an improved model of care.8,11

HISTORY OF THE ROCHESTER MODEL OF CARE

The Rochester Model of Care for geriatric co-management of hip fractures has evolved over a 20-year period. It started with a ‘lean business model’, which has been used successfully in business but rarely applied to medicine.26

The Rochester Model was developed at Highland Hospital, a community hospital affiliated with a major teaching institution in western New York. A formal organized program was initiated in 2004 and was called the Geriatric Fracture Center (GFC). Since its inception, the GFC has become a tertiary referral centre in the region for patients with hip fractures as well as other fractures in the geriatric population. The program has grown and matured with time and this model has been adopted by an estimated 300 other hospitals in the United States, Europe, Latin America and Asia.

HISTORY OF LEAN BUSINESS PRINCIPLES

The Rochester Model of Care employs lean business principles. Lean business principles were developed in Japan during the 1950s by W. Edwards Deming, Taiichi Ohno, Eiji Toyoda and Kiichiro Toyoda.27,28 Deming was an advisor for the United States Army who worked with the Toyoda family, industrialists who owned Toyota Motor Corporation. The goal of this collaboration was to produce motor vehicles with limited resources, less production space, faster changeover times and higher quality.27 Dr. Deming implemented the Plan-do-check-act (PDCA) cycle as a fundamental method of continuous quality improvement. This approach resulted in fewer manufacturing defects and reduced waste. When applied in the automobile sector, the PDCA cycle further improved on the mass production model developed by Henry Ford earlier in the twentieth century. The end result was the spectacular rise of the Japanese motor industry, culminating with Toyota overtaking General Motors as the world’s largest automaker in 2008.29 Taking note of the benefits of this accomplishment, most industries use lean business models as the standard business model for production and service; healthcare is the one notable exception.28,30

Many lessons from the business world can be applied to healthcare, to achieve a reduction in adverse events and improved efficiency, ultimately leading to reduced costs.31 It has been estimated that the percentage of waste is 30–60% in American healthcare.28 This is especially important in the United States, where such a high proportion of the gross domestic product is spent on healthcare.

Lean business principles have been successfully applied to healthcare in the Rochester Model of Care.5,8,11,31 The Rochester Model features standardized order sets, standardized care maps, early surgical intervention and many other standard work processes.31 This standardized work process serves to reduce unwarranted variation and has been shown to improve outcomes at the same time as reducing costs.

THE ROCHESTER MODEL

The program is co-directed by an orthopaedic surgeon and a geriatrician, who share leadership responsibilities. In addition to the attending surgeons and physicians who are part of the program, orthopaedic surgery residents and geriatrics fellows are also involved. A key aspect of the Rochester Model is that, even though the patient is technically admitted to the orthopaedic team, both services have equal and full responsibility for each patient.5 This approach fosters cooperation and avoids ‘turf wars’ about who will admit the patient or look after certain aspects of their care. Essential team members include anaesthesiologists, midlevel providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants), nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, nutritionists and patient care aides, in addition to the patient and family. Consulting providers from medical specialties such as cardiology or neurology are involved only when necessary. All care team members consistently set the same expectations and goals for the patient.

Six principles of care of the Rochester Model

The Rochester Model is based upon six principles of care, which were developed from the Acute Care for Elders model first reported by Covinsky et al.,32 with adaptations for fragility fracture patients.11 These have been updated as follows, based on the experience of the previous decade. The six principles of the GFC are shown in Table 4.1.

MOST HIP FRACTURES REQUIRE SURGERY

Non-ambulatory patients benefit from surgery because they can obtain pain relief and surgical repair facilitates nursing care.33,34 Hip fractures are rarely managed non-operatively. Reasons for non-operative care include refusal to provide surgical consent, limited life expectancy or inability to medically tolerate surgery. Palliative care should be offered to non-operatively treated hip fracture patients.

EARLY SURGERY IS ESSENTIAL TO IMPROVE OUTCOMES

Numerous manuscripts published since 1995 have documented the benefits of early surgical intervention for hip fractures.35,36,37 and 38 The most frequent cause for surgical delay is a poorly functioning system of care. Because this parameter is modifiable, physicians and surgeons should make every effort to promote early surgery. Early surgery lessens the risks of venous thromboembolism, skin breakdown, pulmonary decompensation and infection.39 Surgical delay slows the return to full weight-bearing status and functional recovery.40 Numerous studies have found a reduction in mortality with surgical repair within 48 hours.35,36,37 and 38

Hip fractures are treated as urgent cases, although not emergent. All patients are evaluated by the orthopaedics service in the emergency department. They are seen by a geriatrician on the same day in most cases. Both orthopaedists and geriatricians are available 7 days a week and round on the patient on a daily basis. Surgeries are completed as soon as patients are medically stable and as facilities allow.

Table 4.1 The six principles of care for the Rochester Model of co-management

|

Source: Courtesy of Stephen Kates, MD.

CO-MANAGEMENT WITH FREQUENT COMMUNICATION AVOIDS ADVERSE EVENTS AND PROMOTES COLLEGIALITY

The benefits of geriatric co-management have been well documented by Cohen et al.41 Hospital complications have been frequently shown to be related to communication problems between healthcare providers. Daily communication between team members with shared responsibility for the patient’s care enables providers to successfully manage the medical and surgical aspects of care in the most effective manner. The resulting sense of collegiality improves provider satisfaction and helps to retain providers in the system.

STANDARDIZED PROTOCOLS, ORDER SETS AND CARE PLANS REDUCE VARIATION AND IMPROVE OUTCOMES

Variability in healthcare, as in other businesses, results in unwanted errors, waste and increased costs. Variability can be reduced by using standardized orders and protocols. Standardized order sets enable ‘usual care’ to be a predictable, evidence based, high level standard of care for every hip fracture patient. Practitioners consider the individual circumstances of each patient and adapt the orders to the individual patient’s circumstances and needs. Representatives from each department develop standardized order sets for each step in the process from the emergency department to the ward through the postoperative phases of care. Standard orders address all important topics including pain assessment and management, use of beta blockers, thromboembolic prophylaxis, urinary catheter use and rehabilitation.

DISCHARGE PLANNING BEGINS WHEN THE PATIENT IS ADMITTED

The early involvement of social workers shortens the length of hospital stay by setting goals and plans for the patient and their family. More than 90% of patients are discharged for rehabilitation to a SNF. Developing close relationships with SNFs and long-term care facilities can facilitate this process.

SURGEON AND PHYSICIAN LEADERSHIP IS ESSENTIAL FOR PROGRAM SUCCESS

The authors have learned from implementing the Rochester Model of Care and by helping other surgeons and physicians to develop their own version of the program, that committed surgeon and physician leadership is essential to successfully establish a program and maintain the program over time. Both surgeons and physicians have numerous commitments and responsibilities that require their attention on a daily basis. Only a fully committed leadership team will be successful in maintaining a successful geriatric fracture program in the long term. Needless to say, support from colleagues, nursing staff, therapists, social workers and hospital administration is also essential to establish and maintain a successful program.

STANDARDIZED CARE ACCORDING TO THE ROCHESTER MODEL

Patient-centred, protocol-driven care

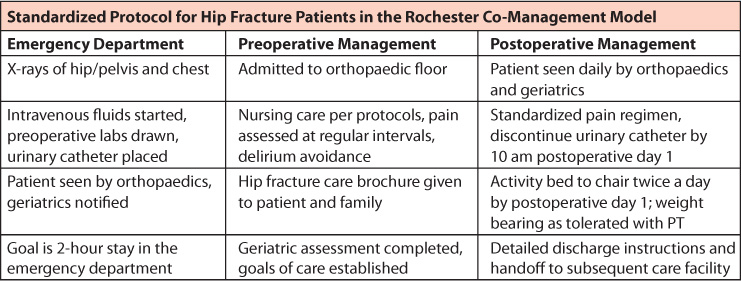

All hip fracture patients in the Rochester Model navigate through a similar care pathway, which is patient-centred yet protocol-driven (Figure 4.1). In the emergency department, X-rays of the hip, pelvis and chest are ordered. Isotonic intravenous fluids are started for rehydration and preoperative laboratory tests sent. A urinary catheter is usually placed and urinalysis is performed to ensure that the patient does not have asymptomatic bacteriuria or urinary tract infection upon presentation. Pain is then assessed at regular intervals with a standard pain regimen. The patient is seen by orthopaedic surgery personnel to admit the patient. A geriatrics consultation is requested. Typically, geriatrics recommendations are provided the same day.

The patient is then admitted preferentially to a designated unit on the orthopaedics service where nursing care protocols are initiated per standardized order sets and care plans. Past medical records are obtained if the patient has no prior entries in the hospital system’s record. The patient is made NPO (nothing by mouth), and intakes and outputs are monitored with pain assessment every 3 hours. If surgery is not expected to be performed within 24 hours, thromboembolic prophylaxis may be indicated. If a patient is taking beta blockers, these are usually continued, and, if not, a decision is made by the geriatrician as to whether a beta blocker is indicated. A bowel regimen is started. Certain medications are avoided, including hypnotics, antihistamines (especially diphenhydramine), anticholinergics and benzodiazepines. Antiemetics are ordered as needed. Finally, a trifold brochure discussing the diagnosis and prognosis of hip fractures is given to the patient and their family. The patient goes to the operating room as early as possible, once they have been assessed and optimized by the geriatrics consultant.

Postoperatively, the patient is seen daily by orthopaedics and geriatrics, with frequent communication between the two teams. Prophylactic antibiotics are continued and a standardized, low-dose opiate pain regimen with around-the-clock acetaminophen is started; the bowel regimen is continued. Anticoagulation is started. Urinary catheters are routinely discontinued by 10:00 am on postoperative day 1 per the standard order set and only occasionally maintained past that time if the geriatrics service is especially concerned about fluid status and the patient is not able to orally rehydrate. Along those lines, intakes and outputs are measured and recorded to assess fluid balance. Oxygen is weaned as tolerated to keep pulse oximetry saturations greater than 89%. The patient is instructed to turn, cough and breathe deeply every 1–2 hours while awake to prevent development of atelectasis. With respect to activity, the patient is mobilized out of bed to a chair twice daily by postoperative day 1. Further activity level is determined by weight-bearing status and cognitive status of the patient. Physical and occupational therapy are also commenced on postoperative day 1, and social work finalizes discharge planning. Postoperative films are usually taken on the first postoperative day.

At discharge, detailed instructions include the names of the doctors involved in the patient’s care, osteoporosis management, medical reconciliation, and follow-up instructions are given to the subsequent care facility.

Standard order sets, consultation forms and discharge forms should be evidence based whenever possible. This helps to reduce errors and minimize waste in the care of these patients. In creating order sets, the total quality management principle is employed so that every facet of care is provided in the safest, most efficient manner possible.42 Another important aspect of this protocol for management of hip fracture patients according to the Rochester Model is the preferential use of generic medications, to help achieve cost savings, and ensure its profitability.

Figure 4.1 All hip fracture patients navigate through a similar patient-centred yet protocol-driven care pathway. The patient is admitted to the orthopaedic surgery service on preferentially designated floors. Geriatrics sees the patient to optimize them for their surgery. Postoperatively, both the orthopaedic surgery and geriatrics teams round on the patient daily, with frequent communication between the care teams. The patient is mobilized on postoperative day 1, and social work is consulted early on. Upon discharge, detailed discharge instructions are given to the subsequent care facility. (Adapted from Friedman SM, et al. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2008; 56(7): 1349–56.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree