2

The Medical Examination

Micki Cuppett and Katie M. Walsh

At the completion of this chapter the reader should be able to do the following:

1. Describe a basic general medical examination, including a comprehensive history and physical examination

2. Differentiate between a focal orthopedic examination and medical examination of conditions that may affect many organ systems

3. Describe and demonstrate the proper use of evaluation tools and techniques for assessment of general health

4. Apply the basics of palpation, percussion, and auscultation in a general medical examination

Examination of the Patient with a Medical Condition

Comprehensive Medical History

A medical health history taken to ascertain the extent of a medical condition or illness is vastly different from an orthopedic history. In an athletic injury, the condition is typically contained within one joint, muscle, or bone and usually involves only the musculoskeletal system. Conversely, a medical condition may involve many body systems, may be difficult to describe, and may not be at all obvious. The clinician needs to appreciate the various types of questions asked in a health history about a medical condition compared with a history for an orthopedic injury. Typical orthopedic questions include the mechanism of injury; sounds associated with the onset (e.g., snap, crunch, pop); and immediate disability associated with the injury, such as swelling, inability to bear weight, deformity, and radiculopathy. Questions in a medical health history review the entire body and include respiratory, gastrointestinal, and neurological symptoms. Questions relating to symptoms are critical because symptoms cannot be measured objectively yet may give clues about the patient’s condition.1 Box 2-1 gives examples of questions to consider asking a patient when taking a history of the patient’s medical condition.

The most common approach to taking a comprehensive medical history begins by identifying and recording a patient’s age and gender. If ethnicity, marital status, occupation, and religion are important to the diagnosis or treatment, they may be documented as well.2 Next, the patient’s chief complaint is identified, including the present illness, onset, and setting when symptoms

were first apparent. Descriptions of the chief complaint that assist the examiner include the following: location of discomfort, quality or quantity of symptoms, frequency, onset, duration, and any associated factors that aggravate or alleviate symptoms. Patients should be asked whether they are currently using medications, supplements, vitamins, home remedies, or poultices. Also, the examiner needs to know whether the patient has shared or borrowed teammates’ or roommates’ prescription medications.

A look into the patient’s family history may provide critical information that can be quite useful in pointing out a susceptibility for a given illness or disease and prove helpful in the examination and care of the patient. Diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, kidney disease, cardiovascular disorders (e.g., deep vein thrombosis [DVT], stroke), allergies, asthma, mental illness, and addictions are all examples of diseases with a genetic tendency. The age, current health, or cause and age at death of immediate family members are also critical factors in determining a family health history. Some physicians add another category, personal and social history, to assist them in understanding their patients better. This category covers a patient’s education, occupation, significant others, home life, daily activities, hobbies, and important beliefs. Although these areas are not necessarily crucial to a specific diagnosis of a given condition, some physicians believe they profoundly affect the overall health and attitude toward wellness in their patients.1

Review of Body Systems

The review of systems continues with the respiratory, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal systems and follows the same cephalocaudal order. Signs associated with respiratory problems include the presence of excessive sputum, altered respiratory sounds, and hemoptysis. The cardiovascular system encompasses the heart and blood vessels, including blood pressure. Symptoms of cardiovascular anomalies encompass murmurs, dyspnea, chest pain, vasovagal responses, hypertension, and syncope. Gastrointestinal problems may manifest with symptoms such as heartburn, nausea, constipation, and food intolerance. Signs include vomiting; change in frequency, consistency, and/or color of stools; rectal bleeding; diarrhea; gas; and jaundice.2

After the cephalocaudal systems review, the evaluation goes on to other prevalent body systems: peripheral vascular, musculoskeletal, neurological, hematological, endocrine, and psychiatric. Important areas to explore include complaints of loss of sensation in the extremities, pitting edema, soreness and swelling in multiple joints, and abnormal fatigue.3 Specific questions pertaining to these systems are discussed later in the appropriate chapters. After the review of all systems, the examiner begins a physical examination of the patient.

Physical Examination

Again, the examiner follows the universally accepted cephalocaudal sequence for the physical examination (Box 2-2). The general survey includes observation of the patient’s apparent state of health, level of consciousness, signs of distress, height and weight, skin color, obvious lesions, and hygiene.4 These are noted as the patient enters the examination area. The practitioner continues the physical assessment in the same order as the previously described review of systems, beginning with the vital signs and skin and advancing from the head down the body. The proper evaluation tools should be ready to expedite the examination.

Vital Signs

Height and Weight

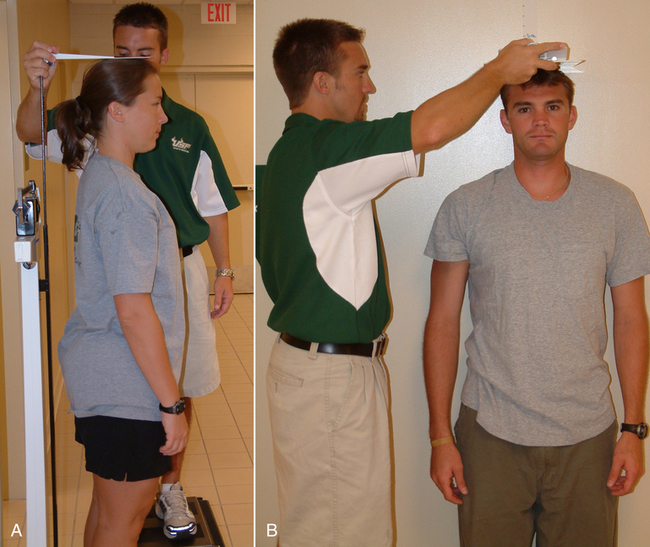

Height is typically measured with a stadiometer or, particularly with extremely tall patients, a tape measure fastened to the wall. The patient removes shoes and stands with the back to the stadiometer or wall, placing all weight on the heels. When using a stadiometer, the clinician stands at the side of the patient and raises the stadiometer to the patient’s height. The horizontal arm rests at the crown of the patient’s head. The height measurement is read on the instrument’s vertical scale (Figure 2-1, A). If not using a stadiometer, the athletic trainer must accurately mark increments on the wall or fasten a tape measure to the wall. The athletic trainer stands to the side of the patient (on a stool if necessary) and uses a flat surface on a sagittal plane along the crown of the patient’s head to evenly mark the height measurement on the wall (Figure 2-1, B). Height may be recorded as either centimeters or inches and should be indicated as such in the medical record (see Appendix B for a chart allowing conversion of inches to centimeters).

Normal body weight is measured without shoes or excessive clothing. Weight is a confidential measurement, so the health care practitioner needs to ensure privacy for the patient during weighing when possible. Weight is typically recorded in medical records in kilograms but may also be recorded in pounds (see Appendix C for a chart allowing conversion of pounds to kilograms). During preseason or excessively warm days, take weight measurements several times each day (preexercise and postexercise) to monitor proper hydration levels and to prevent heat-related illnesses.5,6 Standardization of measurements can be improved by following the same procedures each time height and weight are measured, for example, measuring both height and weight in the morning and having patients wear a standard attire of gym shorts and T-shirt. More accurate assessments of body composition exclusive of height and weight charts include hydrostatic weighing, skinfold calipers, bioimpedance, and body mass index (BMI) (see Appendix D for a BMI chart).

Blood Pressure

A stethoscope and sphygmomanometer of the correct size will measure blood pressure properly. This is especially important for the athletic trainer, who often must evaluate extremely muscular or large athletes for whom a regular size blood pressure cuff is too small. Using a cuff that is too small results in a reading that is incorrect, indicating abnormally high blood pressure. Normal resting blood pressure is measured after the patient has been resting quietly for a period of time; it is never measured immediately after any exertion, such as practice or hurrying to an appointment.7,8

The patient is positioned in a quiet area with the selected arm free of clothing and positioned so that the brachial artery is roughly at heart level, which can be done by having the patient rest the arm on a table next to the chair. The sphygmomanometer is placed around the upper arm with the lower edge of the cuff about 2.5 cm above the antecubital crease (Figure 2-2). The cuff is snugly secured around the arm with the Velcro fasteners, and the aneroid dial is positioned with its face toward the examiner. The diaphragm of the stethoscope is placed lightly over the brachial artery, touching the skin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree