16

Dermatological Conditions

Patrick Sexton, Todd L. Kanzenbach and Mary H. Lien

At the completion of this chapter the reader should be able to do the following:

1. Describe the anatomy of the integumentary system

2. Recognize signs and symptoms of common skin conditions

3. Contrast the differences among viral, fungal, and bacterial skin disorders

4. Refer an athlete with a problematic skin disorder to the appropriate health care provider

5. Recognize environmentally induced conditions: skin cancers, cold injuries

6. Differentiate which acute skin conditions are contraindicated for certain athletic participation

Introduction

Dermatological conditions in athletes are common in a variety of settings and are a major reason that many athletes miss practice or competition. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Injury Surveillance System indicates that dermatological conditions account for 17.2% of practice time–loss injuries in intercollegiate wrestling and that of those, 45.3% are viral infections (herpes simplex and herpes zoster), 24.9% are bacterial infections (including staphylococcal, streptococcal, and impetigo), 22.1% are fungal infections (tinea), and the remaining 7.7% of time-loss skin infections come from a variety of other conditions.1 Although most dermatological conditions are the result of skin-to-skin contact and resultant transmission, some may involve respiratory or airborne transmission. Others may result from allergic reactions, cancer, or insect bites. The five main types of dermatological conditions are as follows: general, bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic. This chapter reviews pertinent anatomy and discusses clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and the criteria for return to participation related to simple dermatological conditions.

Overview of Anatomy and Physiology

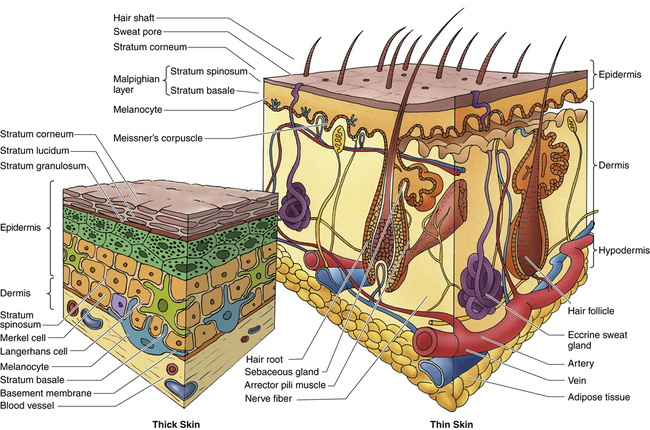

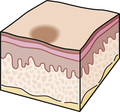

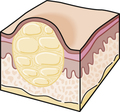

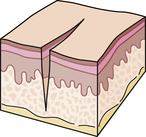

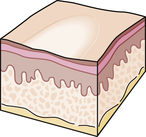

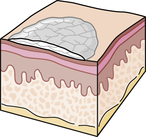

The skin, or integument, is the largest organ of the body and can be divided into three layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous tissue or hypodermis (Figure 16-1). The epidermis itself is composed of up to five layers from deep to superficial: stratum basale; stratum spinosum; stratum granulosum; stratum lucidum, found only in the soles of the feet and palms of the hands; and stratum corneum.2

Each layer of the epidermis except for the stratum basale is composed of dead cells (Box 16-1). The epidermis provides the primary protective shield for the body through the constant formation of new cells and the sloughing of old cells and through the production of pigment known as melanin. The dermis, which is composed of a papillary layer and a reticular layer, contains a variety of vascular and sensory structures, hair follicles, sebaceous or sweat glands, and nails. Finally, the hypodermis, or subcutaneous layer, is made up of connective tissue, which binds the dermis to the deeper structures, and adipose, which provides insulation and cushioning. Together the epidermis, the dermis, and the hypodermis make up the integumentary system.2

The integumentary system serves as the interface between the body and the external environment. It is a dynamic system that serves as a protective barrier against invading organisms and outside influences such as ultraviolet radiation, toxic chemicals, thermal changes, and penetrating forces. However, at the same time, the integumentary system allows people to sense and to adapt to the environment in terms of thermoregulation; fluid loss; proprioception and kinesthesis; force dissipation; cutaneous absorption of gases, ultraviolet light, and toxins; and synthesis of vitamin D. Finally, the skin plays an important role in human communication by helping people to convey emotions through changes in skin color and texture as well as through facial expression.2

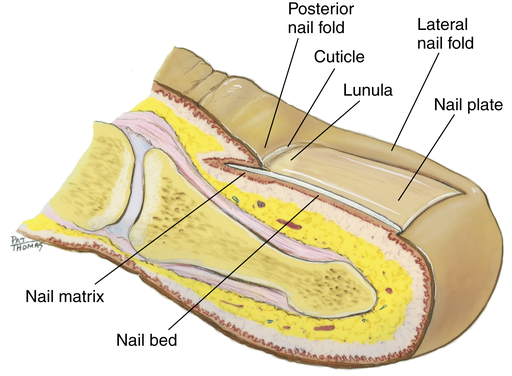

Nails are made up largely of keratin and are found on the dorsal surfaces of all fingers and toes (Figure 16-2). The nail is a hard, clear surface that presents a pink color from the underlying highly vascular epithelial cell layer. The lunula lies at the proximal end of all nails. It is a moon-shaped, white opaque layer that protects the nail matrix, which in turn produces new keratinized cells. The nail fold surrounds the lateral and proximal nail and hooks onto the nail bed. It is in this area that certain bacterial conditions arise.

Evaluation of the Skin

A skin inspection should be conducted in a well-lit room that provides a private, respectful environment. For full-body examination males should be wearing only shorts while females should be wearing shorts and a sports bra or swimsuit top. Whenever possible a health care provider of the same gender should be conducting the examination. Begin the examination with a history by asking the patient if he or she has any skin problems to report, if they have felt ill, nausea, fever, body aches, or fatigue. These symptoms may be especially indicative of viral or bacterial infections. The visual inspection is conducted with the patient standing erect, feet shoulder width apart, arms abducted to 90 degrees, palms forward with hands open. Avoid touching the patient whenever possible; however, this may be unavoidable when examining specific body parts, especially the scalp. If contact is necessary the athletic trainer should wear gloves whenever touching the patient and change gloves and disinfect hands between patients in order to avoid cross-contamination. Begin a systematic inspection of the patient including all aspects of the upper and lower extremities and the torso, including the axilla, the neck, the face, and the scalp. The scalp is especially important because hair may conceal active infections. Patients should be able to adjust their neck and move their hair to facilitate the inspection, but the athletic trainer may have to physically part the hair in order to visualize the scalp.3

The athletic trainer should look for any abnormalities and should note specifically any lesion’s pattern, color, and location3:

Pattern: Does the lesion appear scratched, raised, depressed, in groups or clusters, and is it bullous, moist, dry or crusted, or draining fluid?

Color: What is the color of the lesion, the surrounding tissue or the fluid or crust, and is the color uniform with well-defined borders and symmetry?

Location: Is the lesion above or below the hairline on the scalp, on or near the genitals or mouth?

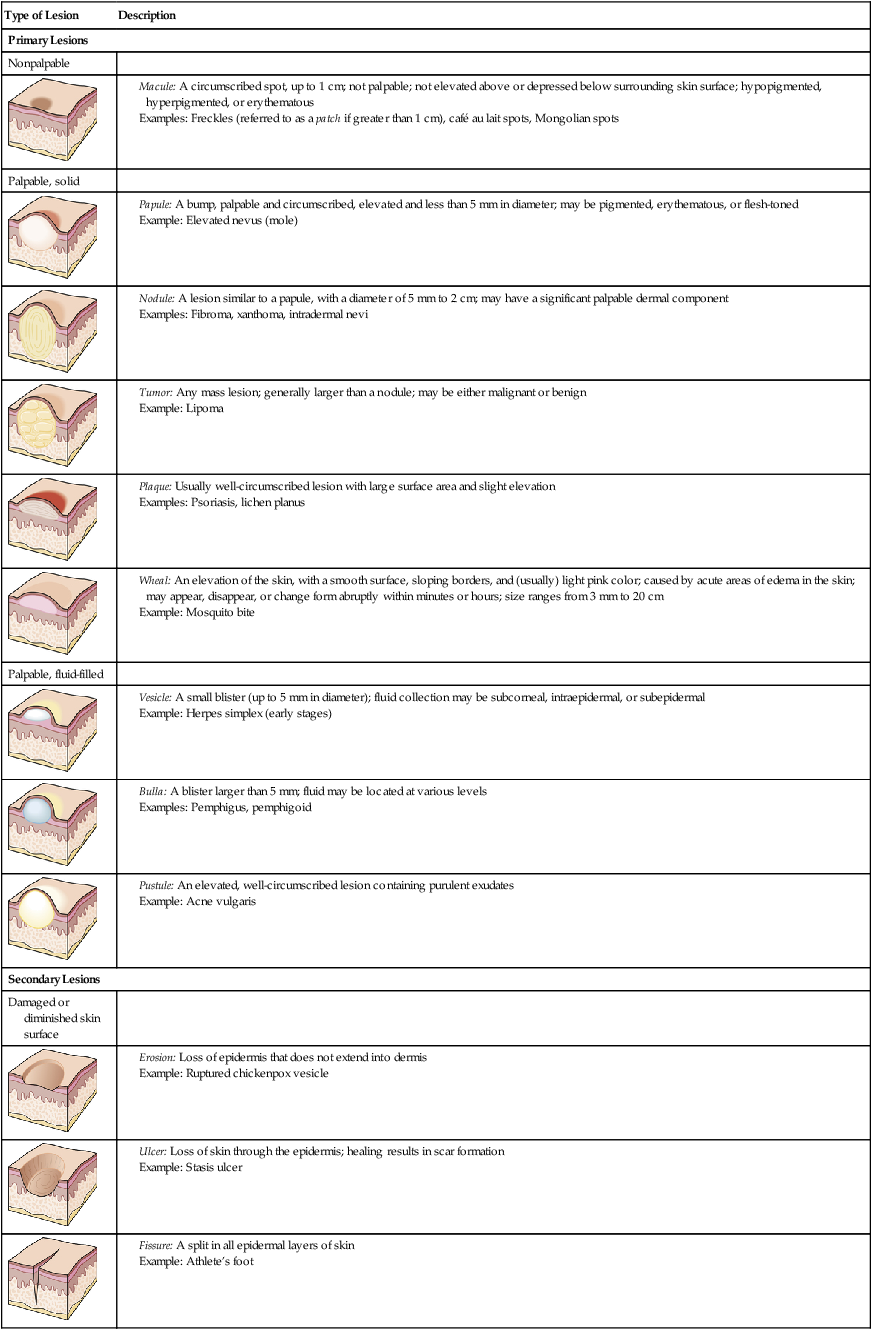

When referral to a medical doctor for evaluation and treatment is necessary, the health care provider must understand the patient’s signs and symptoms and be able to effectively describe findings to the physician, using dermatographical nomenclature. The terminology used to describe the appearance of a skin lesion or condition is very specific. The athletic trainer must have the knowledge and resources necessary to make these distinctions. It is much easier and more efficient to describe the lesion as a “fissure” rather than as a “linear loss of epidermis and dermis with sharp defined borders.” In addition, the clinician must understand that these terms are important to the description and are not a specific diagnosis (Table 16-1).

TABLE 16-1

| Type of Lesion | Description |

| Primary Lesions | |

| Nonpalpable | |

| |

| Palpable, solid | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Palpable, fluid-filled | |

| |

| |

| |

| Secondary Lesions | |

| Damaged or diminished skin surface | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Augmented or increased skin surface | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

From Copstead LEC, Banasik JL: Pathophysiology: biological and behavioral perspectives, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2000, Saunders, pp 1184–1185.

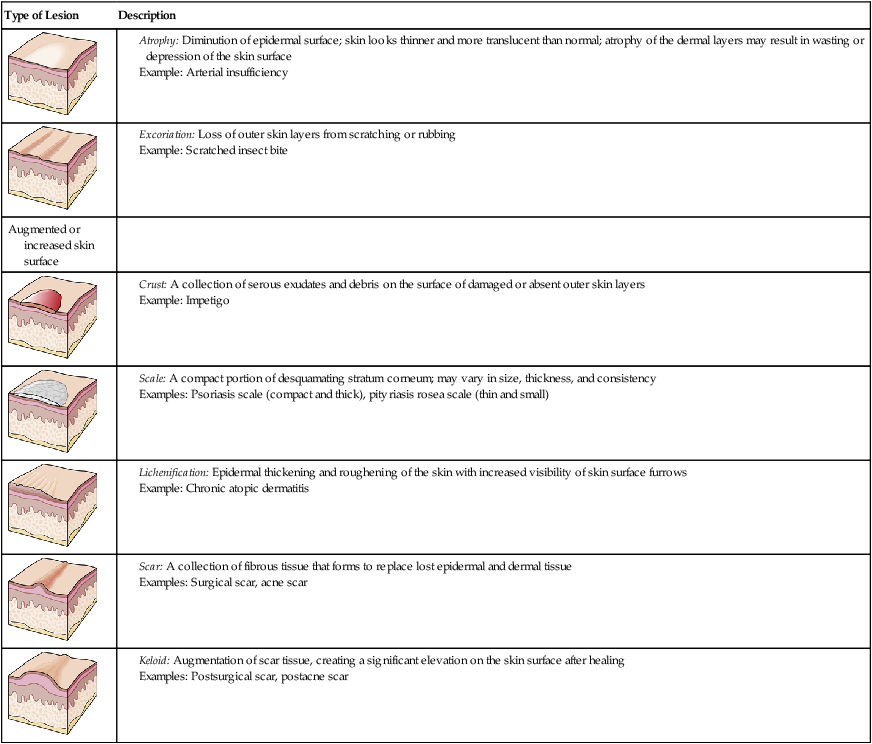

Another way to describe dermatological conditions is by referencing the area of skin affected. Most physicians use millimeters (mm) to describe the width or breadth of a particular condition, but centimeters (cm) are used for larger surface areas. As a point of reference, 1 inch is equal to 25.40 mm or 2.54 cm (Figure 16-3).

Pathological Conditions

Urticaria

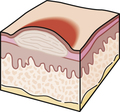

Urticaria is a group of distinct skin conditions characterized by itchy, wheal-and-flare skin reactions, commonly known as hives.4 Urticaria is a common skin pathology that is often seen in athletes. When histamine is released from mast cells, it produces a characteristic triple response: vasodilation causing local erythema, erythematous flare beyond the local erythema, and leakage of fluid causing local tissue edema (Figure 16-4). The majority of cases are acute and can last up to a few weeks. The causes of urticaria are wide ranging and include allergies to foods such as shellfish, nuts, and eggs; food additives such as salicylates, dyes, and sulfites; drugs such as penicillin, aspirin, and sulfonamides; bacterial, viral, and fungal infections; and allergens such as pollens, mold, and animal dander. Internal disease; physical stimuli such as dermatographism, exercise, cholinergic agents, cold, and sun; skin diseases; hormones such as occur during pregnancy; and genetic predisposition can also trigger urticaria. The underlying cause of acute urticaria cannot be determined in about 50% of cases.4 A more rare variety of the condition is chronic urticaria, which arises from chronic infection, intolerance to food additives, or autoreactivity.4 A typical hive is an intensely itchy erythematous or white edematous area. A discussion of general urticaria and specific conditions follows.

Treatment

The most effective treatment is to determine and eliminate the cause, but this is often extremely difficult. Most athletes will need an oral nonsedating antihistamine, such as loratadine (Claritin) or fexofenadine (Allegra), because the sedating antihistamines may impair performance. Another popular antihistamine commonly used for urticaria is cetirizine (Zyrtec), but it also has mild sedative properties although not as severe as the sedating antihistamines listed in Box 16-2. If the aforementioned antihistamines are unsuccessful, the use of glucocorticoids (steroids) has been effective. In emergent situations, in which the athlete’s airway is compromised, use of epinephrine (EpiPen) injection prescribed for that athlete may be warranted. Chapter 4 describes the correct use of an EpiPen.

Dermatographism

Dermatographism is hives induced by rubbing or stroking the skin or by rubbing of the skin with clothing. As many as 2% to 15% of the population may be dermatographical.5 The exact cause is unknown, but recent infections or medications appear to be the most common cause. The hives develop within 1 to 3 minutes of stroking the skin and resolve in 30 to 60 minutes. The patients affected will go through periods of reactivity during their lifetimes, but dermatographism is more common in younger patients.

Signs and Symptoms

Dermatographism presents with blanching and associated linear edema and erythema (Figure 16-5). It can occur on any part of the body because it does not matter if the skin is covered by clothing or equipment. Indeed, the friction caused by clothing or equipment may induce a dermatographical reaction.

Cholinergic Urticaria

Cholinergic urticaria usually develops in younger patients between the ages of 10 and 30 years and resolves spontaneously in only a small percentage of these patients. This reaction consists of 2- to 4-mm hives with surrounding erythema that occur during or shortly after the patient experiences exposure to heat or overheating of the body during exercise, or stress. (Figure 16-6). This reaction typically occurs within 2 to 20 minutes of exposure but may be delayed for up to 1 hour. Signs and symptoms are induced by the parasympathetic nervous system’s release of acetylcholine and may last up to 3 hours.5

Cold Urticaria

Referral, Diagnostic Tests, and Differential Diagnosis

The athletic trainer refers any athlete with extreme reactions to cold to a physician for definitive diagnosis and evaluation for other systemic symptoms. Diagnosis is made in the physician’s office by applying ice to the skin for 1 to 5 minutes or by exposing the forearm to cold water (0° to 8° C; 32° to 46° F) for 5 to 15 minutes and monitoring for hives (Figure 16-7). This is recommended only under the supervision of a physician in a medical facility because systemic symptoms and anaphylaxis may develop. Urticarial vasculitis, cholinergic urticaria, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and dermatographism are all differential diagnoses for cold urticaria.

Solar Urticaria

Solar urticaria is a condition manifested by hives that occur within minutes of exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light and resolving within 1 to 3 hours. The range of the electromagnetic spectrum, or UV light, that causes the hives is between 290 and 500 nm.5 Systemic reactions such as syncope have occurred but are rare. Syncope typically occurs in young adults and more commonly in females shortly after sun exposure.

Prevention

Prevention of solar urticaria consists of decreasing the amount of sun-exposed skin; using sunscreens; and wearing long sleeves, pants, and hats when possible. Most sunscreen agents absorb the ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation (290 to 320 nm) responsible for the development of hives; however, sunscreens that contain avobenzone (also known as Parsol 1789) will absorb UVA I and UVA II wavelengths (340 to 400 nm and 320 to 340 nm, respectively), and sunscreens containing menthyl anthranilate and oxybenzone will absorb UVA II wavelengths.9 All forms of wavelengths are responsible for the development of hives and other skin injuries related to sun exposure.7

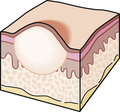

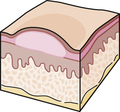

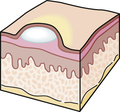

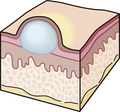

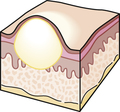

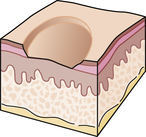

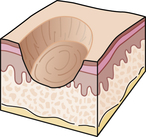

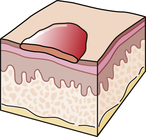

Sebaceous Cysts

Sebaceous cysts, also known as epidermal or keratinous cysts, are very common in young people to middle-aged adults. These cysts have a thin wall filled with a white keratin material produced by the skin epithelium. They are slow growing, movable, and nontender (Figure 16-8).

Dermatitis

Eczema

Eczema is often used synonymously with dermatitis and is the most common inflammatory skin disease. Whereas eczema itself often indicates vesicular dermatitis, some refer to it as chronic dermatitis.10 It consists of three components: erythema, scales, and vesicles. The many causes of eczema include a contact allergic reaction such as to poison ivy, topical medicines including neomycin, atopic dermatitis, fungal infections, dyshidrosis, and habitual scratching. If left alone, most eczematous lesions will resolve, but patients are rarely able to avoid scratching.

Signs and Symptoms

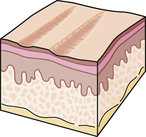

Eczema consists of three stages: acute, subacute, and chronic. The acute stage consists of a red swollen plaque with small vesicles. These lesions are very itchy, appear within days after exposure, and last for days to weeks. The subacute stage consists of erythema and scales of various degrees, which may also itch. The chronic stage consists of thickened skin with increased skin markings and moderate to intense itching (Figure 16-9).

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a genetic, chronic, and recurring disorder that usually begins during childhood. It is a scaling, papular infection similar to eczema but without the epithelial eruptions, wet areas, and crusts. In some cases, a streptococcal infection may precipitate the onset of the disorder. Psoriasis affects an estimated 4% of the population worldwide.10 Psoriasis has a gradual onset and usually has chronic remission and recurrence rates that vary in frequency and duration, but permanent remissions are rare.10

A small percentage of patients with psoriasis also experience psoriatic arthritis.8 The exacerbation-remission cycle common to the skin disorder may coincide with the arthritic component. Most often, the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers and toes are affected. Unlike rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis tends to enter remission more frequently and rapidly than RA, and it lacks the typical joint nodules associated with RA. The patient with psoriatic arthritis may progress to chronic, disabling arthritis, so complaints of joint pain in the psoriatic person must not be overlooked.10

Signs and Symptoms

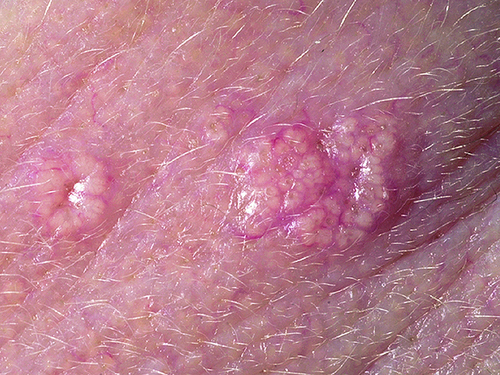

The distinctive lesion of psoriasis is a silvery white plaque with surrounding erythema with distinct borders (Figure 16-10). The lesions usually begin as small, red, scaly papules that coalesce into round or oval plaques except in the skin folds, where they appear as deep red, macerated plaques. These lesions are most common on the extensor surfaces, such as the elbows and knees, but are also very common on the scalp, fingernails, toenails, gluteal clefts, and previous sites of trauma (Figure 16-11).

Treatment

Treatment for psoriasis is complicated and involves the use of topical steroids such as calcipotriol (Dovonex), anthralin ointment, UV light, and steroid injections. Lubricating creams, including hydrogenated vegetable oil, white petrolatum, and crude coal tar, combined with exposure to UV light (280 to 320 nm), have been effective.10 The prescription of oral steroids is contraindicated because of their side effects, which include severe exacerbations of psoriasis.

Environmentally Induced Dermatological Conditions

Skin Cancer

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers

Nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is the most common cancer in humans worldwide. NMSC can be classified into two categories, basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, depending on which type of cell is affected. Both arise from skin cells termed keratinocytes, and rarely spread elsewhere. Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) comprise 75% to 80% of NMSCs whereas squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) comprise up to 25%.11 Whereas BCCs rarely metastasize and are infrequently fatal, SCCs, if left untreated, may lead to significant mortality. Actinic keratoses are considered to be precursors to SCC and are the most frequently treated lesions in humans. Actinic keratoses (AKs) are typically characterized as being “precancers” or premalignant because of the presence of atypical keratinocytes confined to the epidermis. The likelihood of invasive SCC evolving from any given AK has been estimated to occur at a rate of less than 0.1% per lesion per year. AKs characteristically appear on the sun-exposed regions of the body.

An estimated 2 million cases of NMSC were diagnosed in the United States in 2004.12 The number of skin cancer cases in the United States surpassed the number of cases of all other cancers combined. Approximately one in five Americans will develop skin cancer during their lifetime—more than 95% of which will be NMSC.11

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin malignancy and occurs more frequently in males than females (an almost 2:1 ratio).13 The incidence of BCC increases with age, and most occur between the ages of 40 and 79 years.4 The incidence of BCC has risen between 20% and 80% in the past 30 years and is still increasing.14

There are many types of BCC. The most commonly occurring types of BCC are as follows:

The first two are discussed below.

Superficial basal cell carcinoma comprises 9% to 11% of all BCCs and usually is found in patients younger than those who have nodular basal cell carcinoma (mean age, 57 years). This type presents as an asymptomatic, erythematous scaly plaque that enlarges very slowly and typically occurs on the trunk or extremities (Figure 16-12). Superficial BCC may grow to be as large as 15 cm in diameter without ulceration or bleeding. It may be mistaken for psoriasis or a squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The incidence of squamous cell carcinoma has risen over the last several decades at a rate of 3% to 10% per year, with more than 250,000 cases diagnosed yearly in the United States.14 SCC is associated with higher mortality in Caucasians, the elderly, and males.14 Classic invasive SCC is discussed below.

Classic Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma

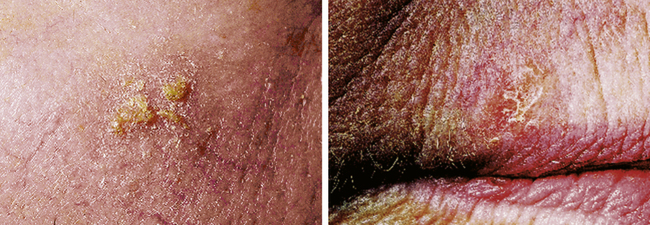

Squamous cell carcinoma occurs on the mucous membranes as well as on sun-exposed skin. SCCs generally arise from actinic keratoses (AKs), which are considered premalignant precursors, at a rate of 0.075% to 0.096% per lesion per year.15 Actinic keratosis presents as an erythematous crusted papule on sun-damaged skin. It is often recognized more easily by touch rather than sight (Figure 16-13). The presence of an AK indicates that skin has been sun-damaged and skin cancer may develop. The most common sites of predilection include the head and neck, dorsal hands, lower lip, and genitalia. SCC commonly develops as a hyperkeratotic erythematous nodule or plaque on sun-damaged skin. Sites with a higher associated risk of metastases include the lip and ear, as well as sites with scarring or inflammation.

Signs, Symptoms and Referral

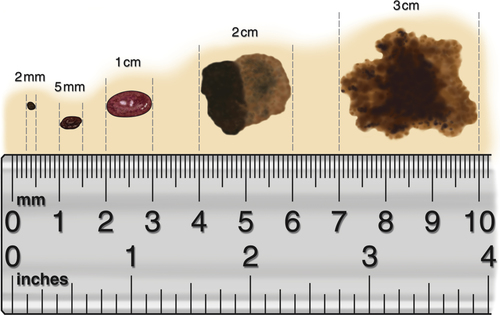

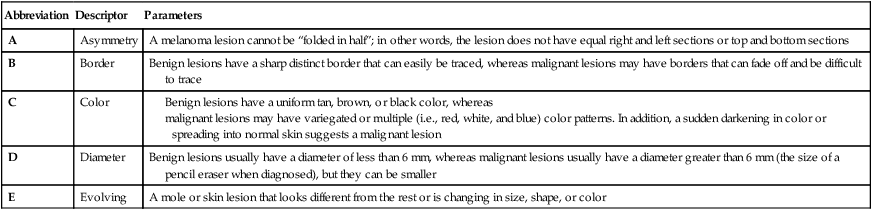

A complete total body skin examination should be performed to rule out any suspicious lesions. Both the American Academy of Dermatology and the American Cancer Society use the ABCD mnemonic as a guide to better recognize suspicious pigmented lesions.16 The ABCD mnemonic is as follows (Table 16-2):

TABLE 16-2

| Abbreviation | Descriptor | Parameters |

| A | Asymmetry | A melanoma lesion cannot be “folded in half”; in other words, the lesion does not have equal right and left sections or top and bottom sections |

| B | Border | Benign lesions have a sharp distinct border that can easily be traced, whereas malignant lesions may have borders that can fade off and be difficult to trace |

| C | Color | |

| D | Diameter | Benign lesions usually have a diameter of less than 6 mm, whereas malignant lesions usually have a diameter greater than 6 mm (the size of a pencil eraser when diagnosed), but they can be smaller |

| E | Evolving | A mole or skin lesion that looks different from the rest or is changing in size, shape, or color |

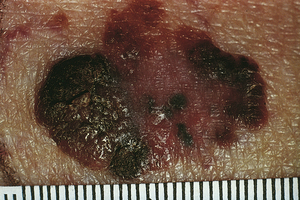

A mole or lesion should have clear, definitive borders. If it does not, the lesion is suspicious and needs to be evaluated by a physician. The athletic trainer needs to refer to a physician any athletes with changes in shape, border, or size of a mole or lesion or the development of ulceration or bleeding, all of which are suggestive of melanoma (see Figure 16-14). Typically a biopsy is performed on a suspicious pigmented lesion. The preferred procedure is an excisional biopsy, as this will allow accurate staging of the tumor. An excisional biopsy, or excision in toto, is a procedure by which the physician cuts away the suspect lesion and its border and evaluates it under a microscope via histopathological examination. The pathologist can then clearly identify the types of cells attributed to the lesion.

It is known that individuals who burn easily typically possess fair skin, blond/red hair, and blue eyes, and therefore, have a higher risk of developing cutaneous (skin) melanoma. However, it is currently not established whether there is any link between ultraviolet radiation exposure and the development of ocular (eye) melanoma.17

Treatment of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

Although benign moles, freckles, and age spots may provoke suspicion, it is wise to refer any questionable lesion to a medical doctor for inspection and likely a biopsy. If caught early, surgically removed melanoma has a high cure rate, but once it metastasizes to the lymph nodes, the 5-year survival rate drops to 30% to 40%.18,19 If organ involvement has occurred through this spread, the survival rate drops again to 12%.9 Excision includes removing at least 1 cm lateral to the tumor.20 Large surgical areas may require skin grafts or loss of underlying tissue that could result in deformity of the area involved.

Melanoma

Melanoma is a skin cancer arising from melanocytes; the lifetime risk for Caucasian Americans is more than 1 in 79.9 Melanocytes are found in the stratum basale (deepest layer of the epidermis), eye, inner ear, meninges, heart, and bone. They produce the pigmentation in skin, also known as melanin. The risk of melanoma will surely grow with the increasing number of people exposed to UV light from either the sun or tanning booths.21 The rate of malignant melanoma has increased by an alarming 190% since the 1930s, has tripled since 1980, and is growing at more than 9% per year.22 The American Cancer Society listed 68,720 diagnosed cases of melanoma in the United States in 2009, and 8,650 deaths.23 The most susceptible individuals have fair skin and blue eyes, sunburn easily, had multiple sunburns at an early age, and have a personal or family history of skin cancer.21,23 Because 40% to 50% of malignant melanomas arise from pigmented moles, people with moles or freckles should be especially cautious.10

Melanoma is a malignancy originating from the pigment-producing skin cell, or melanocyte, and is one of the most common types of skin cancer in young adults. Because of its recent rising incidence and overall mortality rate, melanoma is recognized as a public health issue. The incidence of melanoma in the United States has increased 15-fold over the past 40 years. Approximately one American dies every hour from melanoma.19 Notably, melanoma kills young adults more frequently than most other cancers.24 Significant attempts have been made to increase public awareness through public sun protection campaigns for the past 25 years. In fact, the health campaigns may be a factor in the decreasing incidence and mortality in young adults in Australia noted in 2002.20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree