CHAPTER 12 The foot

The first metatarsophalangeal joint

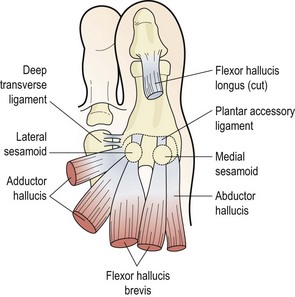

The first metatarsal bone joins proximally to the first cuneiform to form the first ray complex. Distally, the bone forms the first metatarsophalangeal (MP) joint with the proximal phalanx of the hallux. The first MP joint is reinforced over its plantar aspect by an area of fibrocartilage known as the volar plate (plantar accessory ligament). This is formed from the deep transverse metatarsal ligament, and the tendons of flexor hallucis brevis, adductor hallucis, and abductor hallucis. It has within it two sesamoid bones which serve as weight-bearing points for the metatarsal head (Fig. 12.1).

Turf toe

Turf toe is a sprain involving the plantar aspect of the capsule of the first MP joint. It is most often seen in athletes who play regularly on synthetic surfaces, and results from forced hyperextension (dorsiflexion) of the first MP joint. Normally this joint has a range of 50–60°, but with trauma the range may be forced to over 100°. The condition is quite common, with studies of American football players showing that 45% of athletes had suffered from turf toe at some stage (Rodeo et al., 1989a).

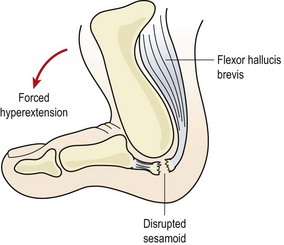

Forced hyperextension of the first MP joint causes capsular tearing, collateral ligament damage and damage to the plantar accessory ligament. Sometimes force is so great that disruption of the medial sesamoid occurs (Fig. 12.2). Examination reveals a hyperaemic swollen joint with tenderness over the plantar surface of the metatarsal head. Local bruising may develop within 24 hours. Differential diagnosis must be made from sesamoid stress fracture (insidious onset) and metatarsal or phalangeal fractures (site of pain and radiograph).

Figure 12.2 Forced hyperextension causes soft tissue damage and possible sesamoid disruption—’turf toe’.

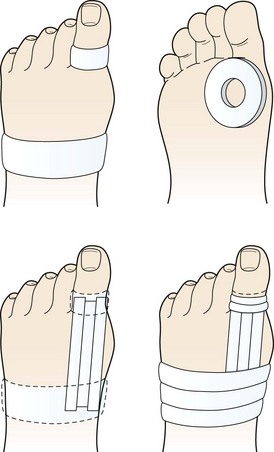

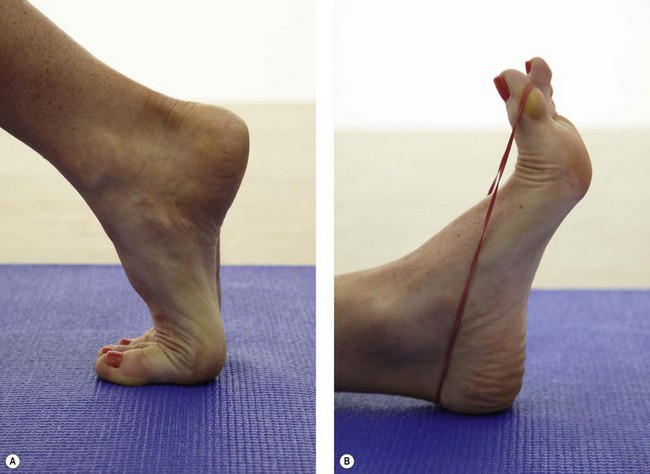

Treatment aims at reducing pain and inflammation and supporting the joint by taping (Fig. 12.3). An oval piece of felt or foam with a hole in the middle is placed beneath the toe, the hole corresponding to the metatarsal head. The first MP joint is held in neutral position and anchors are applied around the first phalanx and mid-foot. Strips of 2.5 cm inelastic tape are applied as stirrups between the anchors on the dorsal and plantar aspects of the toe. In each case the tape starts at the toe and is pulled towards the mid-foot, covering the first MP joint. The mid-foot and phalanx strips are finished with fixing strips.

A number of factors may predispose the athlete to turf toe. The condition is more common with artificial playing surfaces than with grass (Bowers and Martin, 1976). Artificial turf is less shock-absorbing, and so transmits more force directly to the first MP joint. Sports shoes also have an important part to play. Lighter shoes tend to be used with artificial playing surfaces. These shoes are more flexible around the distal forefoot, and allow the MP joint to hyperextend. In addition, shoes which are fitted by length size alone, rather than width, may cause problems for athletes with wider feet. This person must buy shoes which are too long to accommodate his or her foot width. Such a shoe increases the leverage forces acting on the toe joints and allows the foot to slide forwards in the shoe, increasing the speed of movement at the joint.

Preventive measures include wearing shoes with more rigid soles to avoid hyperextension of the injured joint. In addition, semi-rigid (spring steel or heat-sensitive plastic) insoles may be used. Some authors recommend the use of rigid insoles as a preventive measure when playing on all-weather surfaces, for all athletes with less than 60° dorsiflexion at the first MP joint (Clanton, Butler and Eggert, 1986).

An increased range of ankle dorsiflexion has been suggested as a risk factor which may predispose an athlete to turf toe (Rodeo et al., 1989b). However, in walking subjects, when the ankle is strapped to reduce dorsiflexion, the heel actually lifts up earlier in the gait cycle, causing the range of motion at the metatarsal heads to increase (Carmines, Nunley and McElhaney, 1988). This increased range may once again predispose the athlete to turf toe (George, 1989), so the amount of dorsiflexion per se may not be that important. If injury has recently changed the range, the athlete may not have had time to fully adapt to the altered movement pattern, and the altered foot/ankle mechanics in total may be the problem.

Hallus valgus

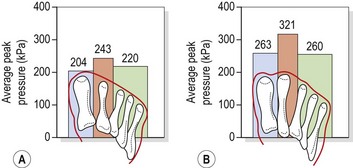

Hallux valgus (hallux abductovalgus or HAV) usually occurs when the first MP joint is hypermobile, and the first ray is shorter than the second (Morton foot structure). When this is the case, the second metatarsal head takes more pressure than in a non-Morton foot (Rodgers and Cavanagh, 1989) (Fig. 12.4). In addition, hallux valgus is more common in athletes who hyperpronate. Often the combination of hyperpronation and poorly supporting fashion footwear exacerbates the condition.

Figure 12.4 Pressure distribution in (A) Morton and (B) non-Morton feet.

From Rodgers, M.M. and Cavanagh, P.R. (1989) Pressure distribution in Morton’s foot structure. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 21, 23–28. With permission.

Pronation of the subtaloid joint reduces the stabilizing effect of the peroneus longus muscle, allowing the 1st metatarsal to displace more easily. The increased motion leads to the combined deformity of abduction and external rotation of the first toe (phalanges) and adduction and internal rotation of the first metatarsal. Joint displacement occurs at both the MP joint and the metatarsal/medial cuneiform joint (Lorimer et al., 2002).

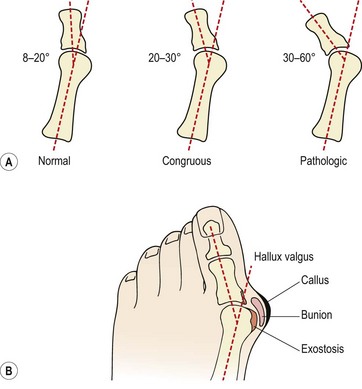

Hallux valgus may occur in one of two types. Congrous hallux valgus is an exaggeration of the normal angulation between the metatarsal and the phalanx of the 1st toe. Importantly the joint surfaces remain in opposition and the condition does not progress. The normal angulation of the 1st MPJ (measured between the long axis of the metatarsal and that of the proximal phalanx) is 8–20°; in congruous hallux valgus this angle may increase to 20–30° (Fig. 12.5A). Once the angle increases above 30°, the joint surfaces move out of congruity and may eventually sublux. This condition is now classified as pathological hallux valgus, and may progress, with the angulation increasing to as much as 60° (Magee, 2002).

Figure 12.5 Hallux valgus. (A) Metatarsophalangeal angle and (B) appearance.

After Magee (2002) with permission.

Bunion formation to the side of the first metatarsal head is common. The bursa over the medial aspect of the MPJ thickens and a callus develops. In time an exostosis is seen on the metatarsal head and the three structures combined lead to the cosmetic change which is noticeable (Fig. 12.5B). A gel padded bunion shield can help reduce both abnormal shearing and compressive stress to ease symptoms when walking. At night a bunion regulator which resists the abduction forces acting on the 1st toe can help to protect the overstretched soft tissues and reduce inflammation and pain.

Hallux limitus/rigidus

Limitation of motion through muscle tightness responds well to stretching procedures, while joint limitation which is soft tissue in nature is treated by joint mobilization. Distal distraction and gliding mobilizations with the metatarsal head stabilized are particularly useful (Cibulka, 1990). Where bony deformity is present, surgery is indicated. A number of surgical procedures are available for hallux conditions, and the interested reader is referred to Horn and Subotnick (1989) for an excellent review.

Plantar fasciitis

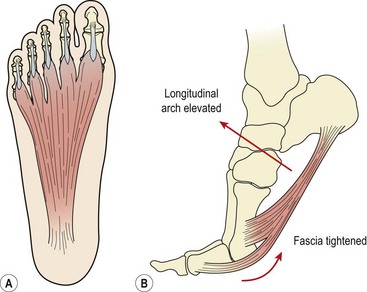

The plantar fascia (plantar aponeurosis) is the thickest fascia in the body. It attaches from a point just behind the medial tubercle of calcaneus and runs anteriorly as five slips. As the slips approach the metatarsal heads, they split into superficial and deep layers (Fig. 12.6A). The superficial layer attaches to superficial fascia beneath the skin, while the deep layer divides into medial and lateral portions to allow the passage of the flexor tendons. Each of the five portions attaches to the base of a proximal phalanx and to the deep transverse ligament.

As the toes dorsiflex and the 1st MP joint is extended prior to toe off, the fascia is wound around the metatarsal head (windlass effect). In so doing the fascia is tightened, shortening the foot and elevating the longitudinal arch (Fig. 12.6B). The combination of these effects supinates the foot and provides a rigid lever for push off. As the foot contacts the ground at heel strike the arch lowers and the foot pronates, becoming a mobile adaptive unit. The plantar fascia is stretched as the foot lengthens.

As we have seen in Chapters 10 and 11 tendon inflammation (patella tendonitis and Achilles tendonitis) is now thought to be an incorrect term based on the pathology of the tissue affected. Similarly the term plantar fasciitis implies tissue inflammation but histological findings do not support this concept. Reviewing 50 post surgical cases Lemont, Ammirati and Usen (2003) found degeneration and fragmentation of the plantar fascia together with bone marrow vascular ectasia (expansion). No inflammatory markers were present, implying that the condition is a fasciosis rather than a fasciitis. This fact is important when treating the condition, as steroid injections (anti-inflammatory) often used to treat plantar pain have a strong association with plantar ruptures (Murphy, 2006). In a study of 765 patients with plantar fascial pain Acevedo and Beskin (1998) found 51 patients who had received corticosteriod injection. Of this subgroup 44 ruptured, with 68% showing sudden onset tearing and 32% gradual onset tearing. At follow-up 26 subjects still showed symptoms 1 year after rupture.

Pain in the plantar fascia is common in sports which involve repeated jumping, and with hill running. Overuse may cause microtears and degeneration at the fascial insertion, and nodules from the fascial granuloma can occasionally be felt (Tanner and Harvey, 1988).

Normally, during mid-stance the foot is flattened, stretching the plantar fascia and enabling it to store elastic energy to be released at toe off. However, a variety of malalignment faults may increase stress on the fascia. Excessive rearfoot pronation will lower the arch and overstretch the fascia, and a reduction in mobility of the first metatarsal may also contribute to the condition (Creighton and Olson, 1987). In addition, weak peronei, often the result of incomplete rehabilitation following ankle sprains, will reduce the support on the arch, thus stressing the plantar fascia. Congenital problems such as pes cavus will also leave an athlete more susceptible to plantar fasciitis. The condition is exacerbated if the Achilles tendon is tight, or if high-heeled shoes are worn. Pain is often worse when taking the first few steps in the morning until the Achilles tendon is stretched.

Treatment

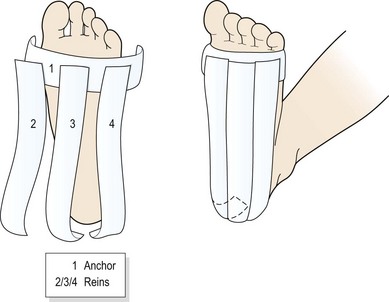

Taping the foot (Fig. 12.7) may often give surprisingly rapid relief. The foot is locked in neutral position and an anchor strap placed just behind the metatarsal heads. Three strips of tape (medial, lateral and central) are then passed from the anchor over the heel to stop on the posterior aspect of the calcaneum. A horseshoe-shaped fixing strip secures the tape behind the heel. Additional strips may be placed transversely across the foot from the metatarsal heads to the calcaneal tubercle.

Extensibility of the 1st MP joint is assessed both weight bearing (foot on the floor) and non-weight bearing (patient on the couch), with normal values of 65° quoted (Murphy, 2006). Movement limitation should be categorized as bony requiring joint mobilization or soft tissue requiring stretching. The plantar fascia is stretched by using a combination of 1st MP extension and ankle dorsiflexion (Fig. 12.8).

Heel pad

Athletes who wear poorly padded sports shoes and those who land heavily on the heel when jumping may bruise this area. In more severe cases rupture of the fibrous septa may occur causing spillage of the enclosed fat cells (Reid, 1992). In turn, the loss of the heel pad shock-absorbing mechanism places excessive compression stress onto the calcaneum.

Management is by additional padding, and preventing the heel pad from spreading. Non-bottoming shock-absorbing materials are useful, and taping to surround the heel and prevent spread of the pad is effective in the short term (Fig. 12.9). Activity modification is required during the acute stage of the condition.

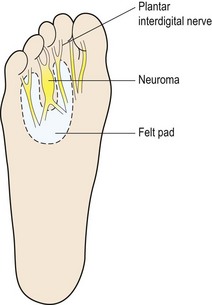

Morton’s neuroma

If the condition is caught in its oedematous stage, alteration of footwear (larger toe box and lower heel), ice application and ultrasound are effective. Injection with corticosteroid and local anaesthetic is also used. Padding the area with orthopaedic felt (Fig. 12.10) to take some of the bodyweight off the neuroma can give temporary relief. The arms of the pad rest on the adjacent metatarsals, leaving the area of the neuroma free.

Once the neuroma has formed, surgical excision under local anaesthesia may be required, with some studies showing improvement in 80% of patients (Mann and Reynolds, 1983). There may be a permanent loss of sensation over the plantar aspect of the foot supplied by the digital nerve, but in some cases regeneration can occur between 8 and 12 months after surgery. Follow-up after 2 years (mean 29 months) has shown an 88% reduction in pain with overall satisfaction being excellent or good in 93% of sporting patients (Akermark, Saartok T and Zuber, 2008).

Freiberg’s disease

Freiberg’s disease (lesion) is an osteochondrosis of the 2nd metatarsal head, most commonly seen in young ballet dancers. Pain occurs over the bony head of the metatarsal (contrast this with Morton’s neuroma which gives pain between the metatarsals) and is aggravated by raise onto the ball of the foot. In longer standing cases x-ray reveals flattening of the metatarsal head with damage to the epiphyseal plate. Initially no changes may be apparent on radiographs (Fig. 12.11), with bone scan or MRI being more sensitive. Management is by modification of weight bearing activities and padding over the metatarsal head to offload the joint and reduce direct pressure over the painful area. Orthotic prescription is often required.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree