44 The Eye and Rheumatic Diseases

During a lifetime, about 40% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis develop acute anterior uveitis.

Sarcoidosis frequently manifests as a uveitis.

Most patients with retinal vasculitis do not have a systemic vasculitis.

Many patients with scleritis have a systemic disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is the most common ocular manifestation of temporal arteritis.

Most patients with visual loss secondary to optic nerve ischemia do not have arteritis.

Virtually all of the systemic inflammatory diseases that require rheumatologic care tend to affect the eye or its surrounding structures. Table 44-1 presents the prototypic ocular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, spondyloarthropathies, vasculitides including granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis) and temporal arteritis, scleroderma, Behçet’s syndrome, relapsing polychondritis, and dermatomyositis. Each of these diseases is addressed elsewhere in this text; this chapter focuses on specific ocular structures—the uvea, cornea, orbit, and optic nerve—and illustrates how inflammation of each might relate to an autoimmune or inflammatory process.

Table 44-1 Most Characteristic Ocular Findings of Selected Rheumatic Diseases

| Disease | Most Characteristic Eye Findings |

|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Sicca Scleritis |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Sicca Cotton-wool spots |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | Sicca |

| Spondyloarthritis | Acute anterior uveitis |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Scleritis Orbital inflammation |

| Temporal arteritis | Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy |

| Scleroderma | Sicca |

| Behçet’s disease | Uveitis, retinal arteritis |

| Relapsing polychondritis | Scleritis, episcleritis, uveitis |

| Dermatomyositis | Heliotrope eyelids |

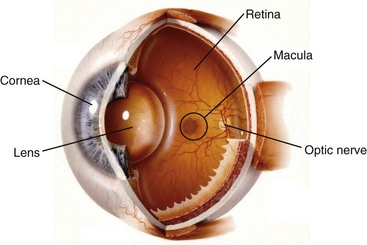

Ocular Anatomy and Physiology

A diagram of the eye is shown in Figure 44-1. The eye is a tiny, but elegantly complex structure. The anterior segment of the eye includes the cornea, which is avascular and transparent when healthy. The lens also is an avascular structure. The anterior chamber is filled with aqueous humor, which has homology to cerebrospinal fluid. When the blood-aqueous barrier is intact, the aqueous humor contains no leukocytes and very little protein. The blood-aqueous barrier, which resembles the blood-synovial barrier, is disrupted in anterior uveitis. In this case, a routine, noninvasive biomicroscopic or slit lamp examination would reveal leukocytes and increased protein in the anterior chamber. An ophthalmologist has the opportunity to observe two universal hallmarks of inflammation noninvasively.

The term uvea derives from the Latin word for “grape.” The anterior uvea includes the iris and the ciliary body. The aqueous humor is synthesized by the ciliary body. The posterior portion of the uvea is the choroid, which is a highly vascular tissue just posterior to the retina. Any portion of the uveal tract could become inflamed; adjacent tissue also is frequently inflamed. Anatomic subsets of uveitis include anterior uveitis, which consists of iritis or iridocyclitis (ciliary body inflammation); intermediate uveitis, in which leukocytes are present within the vitreous humor; and posterior uveitis, in which the choroid and the retina are inflamed. A panuveitis occurs when all portions of the uveal tract are inflamed. An attempt has been made to standardize the nomenclature used to describe uveitis by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group,1 although ambiguities persist because not all ophthalmologists follow these definitions as yet.

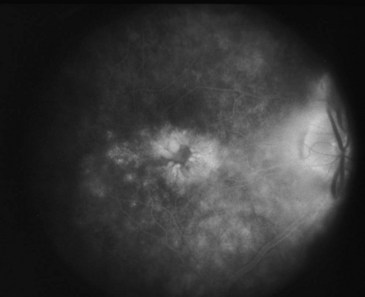

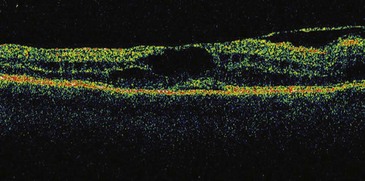

Signs and symptoms of uveitis depend on the portion of the uveal tract that is affected. An anterior uveitis, especially if it begins suddenly, is associated with redness, pain, and photophobia. Visual loss varies and often is due to macular edema if present (Figures 44-2 and 44-3). An intermediate uveitis usually causes floaters owing to leukocytes that enter the visual axis, although most floaters are due to aging or other changes within the vitreous humor. A posterior uveitis by itself does not usually produce pain or redness. Visual loss depends on the location and extent of the inflammatory process.

The outer tunic of the eye is known as the sclera. At the front of the eye, the sclera meets the cornea at a tissue known as the limbus. The most interior layer of the eye is an extension of the brain that responds to visual signals, the retina. The eye shares some common features with the joint, including the presence of hyaluronic acid primarily in the vitreous humor and the presence of type II collagen, although ocular inflammation is not a reported accompaniment of collagen-induced arthritis. Aggrecan is a proteoglycan present in both the eye and the joint. An autoimmune response to aggrecan in BALB/c mice can produce both arthritis and uveitis.2

Ocular Immune Response

The eye generally is regarded as an immune privileged site.3 From a teleologic perspective, many scientists believe that the eye has evolved mechanisms to avoid becoming inflamed because of the consequences this has for visual acuity. Similar to the brain, the internal portion of the eye has no lymphatics, although the conjunctiva on the ocular surface has lymphatic drainage. Portions of the eye—the cornea and the lens—are avascular. The aqueous humor contains several factors that are known to be immunosuppressive, including transforming growth factor-β and α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone. Several tissues within the eye express ligands that promote apoptosis, including tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and Fas ligand. If a soluble antigen is injected into the anterior chamber, a cellular immune response is suppressed. This phenomenon is known as anterior chamber–associated immune deviation (ACAID). These factors are important to consider in the effort to understand why the eye sometimes is targeted as part of an immune or inflammatory disease.

Uveitis

Rheumatologists may be consulted to identify a systemic disease in a patient with uveitis, and a rheumatologist often is asked to assist in the management of immunosuppression in selected patients with uveitis. In some referral practices for patients with uveitis, 40% of patients might have an associated systemic illness. Table 44-2 lists the differential diagnoses of uveitis. The immunologic diseases most likely to be associated with uveitis are listed in Table 44-3.

Table 44-2 Differential Diagnosis of Uveitis

Table 44-3 Immune-Mediated Diseases Most Often Associated with Uveitis

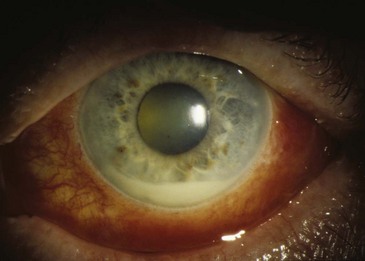

The most common systemic illness associated with uveitis in most North American practices is ankylosing spondylitis. From an epidemiologic perspective, anterior uveitis is more common than posterior or intermediate uveitis.4 About 50% of individuals who develop an anterior uveitis are HLA-B27 positive.5 The uveitis associated with HLA-B27 is almost always unilateral, is recurrent, is of relatively short duration (<3 months per attack), resolves completely between attacks, and is associated with reduced intraocular pressure (in contrast to herpes simplex, which can cause recurrent anterior uveitis associated with increased intraocular pressure).6 Hypopyon or pus in the anterior chamber sometimes is present in patients with HLA-B27–associated uveitis (Figure 44-4). Recurrent episodes can affect the contralateral eye, but simultaneous bilateral involvement is rare. Many studies have tried to address the question of how frequently a patient with HLA-B27–associated anterior uveitis has an associated spondyloarthropathy. A wide range of answers have been suggested, and the percentage depends on the definition of spondyloarthropathy, but one reasonable estimate is that 80% of HLA-B27 positive patients with acute anterior, unilateral uveitis have associated spondyloarthropathy.5

Figure 44-4 The creamy material at the bottom of the pupil is an accumulation of leukocytes, also known as a hypopyon.

The uveitis associated with reactive arthritis is indistinguishable from the uveitis associated with ankylosing spondylitis. In either of these entities, about 40% of patients develop acute anterior uveitis during a lifetime. Although conjunctivitis is part of the classic triad of reactive arthritis (in association with arthritis and nongonococcal urethritis), conjunctivitis is uncommon. A genome-wide screen for susceptibility genes for acute anterior uveitis identified loci that predispose to ankylosing spondylitis and loci that seem to be unassociated with susceptibility to ankylosing spondylitis.7

Approximately 5% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and 7% of those with psoriatic arthritis develop uveitis. Although some of these patients have disease that is unilateral, anterior, and recurrent, many have disease that is bilateral, chronic in duration, and posterior to the lens.8,9 About half of all patients with Crohn’s disease or psoriatic arthritis and uveitis are HLA-B27 positive.

Sarcoidosis is the second most common systemic disease associated with uveitis, at least in North America, and in some geographic areas it might be more common than spondyloarthritis. Sarcoidosis is promiscuous within the eye, meaning that it can affect a wide range of structures, including the orbit, lacrimal gland, anterior uvea, vitreous humor, choroid, retina, or optic nerve. Ocular inflammation with sarcoidosis frequently is termed granulomatous because large collections of cells deposit on the back of the cornea (Figure 44-5). A retinal vasculitis can be a prominent feature of sarcoidosis, even though systemic vasculitis is not a typical feature of the disease; this results in part from the manner in which vasculitis is diagnosed in the retina.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree