CHAPTER 3 Taping in sport

Taping materials

Various forms of tape are available, either elastic or inelastic. In general, elastic tape is used with injured contractile tissue to provide a graded resistance or compression. Inelastic tape is more often used with non-contractile tissue injuries, to take the place of a ligament in reinforcing a joint. Zinc oxide tape is the most common inelastic type. It is air permeable, allowing the skin to breathe and some moisture to escape through the tape. The tape is backed with a strong adhesive which may be a hypoallergenic formation. The tape strength is largely dependent on the number of individual threads per inch, a value known as the thread count (Lutz et al., 1993). The higher quality tapes generally have a higher thread count and are therefore stronger and less affected by body heat and moisture. The edge of zinc oxide taping may be serrated to make tearing off strips of tape during application easier.

The elastic tapes may be either adhesive backed or adherent. Adhesive elastic tapes will normally stretch both longitudinally and transversely. Typically, this type of tape will recoil to 125% of its original length when initially stretched lengthways (Austin, Gwynn-Brett and Marshall, 1994). However, multiple stretching will cause the tape to fatigue. Rather than tensile strength, elastic tape has good compression qualities and will pull on the skin if applied pre-stretched.

Beneath the tape, padding materials are used to protect the skin or bony prominences and to fill in superficial anatomical cavities. The padding may be either foam or fibre based. Polyester urethane foam underwrap is used to prevent tape adhering to the skin and to provide a more even compression. Fibre padding such as orthopaedic felt, or its synthetic equivalent, is used where thicker packing is required. These have the advantage that they may be cut and shaped. A variety of taping supplies are listed in Table 3.1.

| Taping and padding materials |

| Skin care preparations |

| Instruments/apparatus |

From Norris (1994), with permission.

Contraindications

There are several contraindications and cautions to taping (Table 3.2). Taping should not be applied unless the patient can be fully assessed. In the sport situation it is all too easy to be rushed into applying tape at the request of a player or coach, but tape must not be applied without patient assessment. Where either skin sensation or skin blood flow is compromised, taping must not be applied. Sensation can be assessed by simple skin tests of the affected area in comparison with the uninjured side. Skin blood flow can be judged by skin colour and texture, and with the limbs compression of the nail bed can be used. As the bed is compressed the skin beneath will go white, but the normal red colour should return within 10 seconds if the blood flow is normal.

Table 3.2 Contraindications and cautions to sports tape application

Keypoint

Taping should not be applied to areas of skin where sensation or blood flow is compromised.

Application

Skin preparation

Keypoint

Mechanical irritation of the skin may occur if taping is not secured correctly, and begins to slip.

Tape application

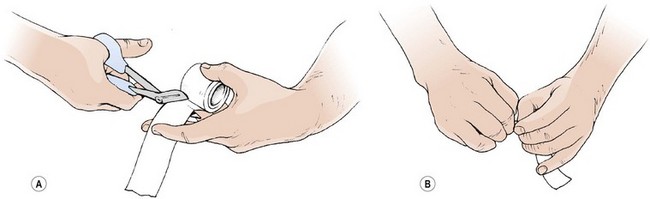

Tape may be either cut or torn prior to application. To cut tape, it should be loosely folded over the lower blade of the scissors with the non-adhesive face inwards (Fig. 3.1A). If the adhesive face is directed outwards, the tape will stick to the scissors and jam between the blades. When tearing tape, speed rather than strength is the deciding factor. The tape should be stretched over the tips of the thumbs with the non-adhesive face inwards. The thumbs should be held together, and one hand twisted against the other with the aim of rapidly breaking the tape edge (Fig. 3.1B). The faster the action, the less strength required.

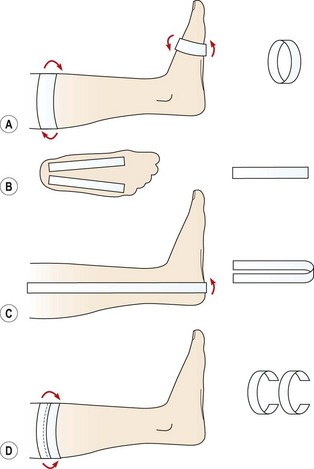

Where strapping is applied in layers, the overlap between successive pieces is normally half the width of the tape. This ensures that the tape layers do not part with movement of the body (Adams, 1985). Gapping of the tape can trap skin between the tape layers, causing skin damage. The tape should be applied smoothly and moulded to the anatomical contours of the body part. Creases should be avoided as these will create pressure spots. Tape is secured to the skin via anchoring strips (Fig. 3.2A). These are either elastic or inelastic strips applied directly to the skin without traction. Care must be taken not to compress the skin as the anchor tape is surrounding the limb and can easily impair the circulation. From the anchors, reins or stirrups may be attached, under traction. A rein travels between two anchor strips (Fig. 3.2B), while a stirrup is a U-shaped loop which passes beneath a body part, for example under the heel and up either side of the shin (Fig. 3.2C). The reins or stirrups are applied along the length of anatomical structures or to pull a joint into a particular position. They relieve stress from ligaments or perform the actions which a muscle would perform were it to contract. Care must be taken to avoid tape slippage which can lead to a friction burn of the skin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree