14

Systemic Disorders

Christine Curran and Joseph Garry

At the completion of this chapter the reader should be able to do the following:

1. Appreciate the complexity of systemic disorders

2. Recognize signs and symptoms of common systemic ailments

3. Identify conditions that warrant referral to a physician

4. Relate the warning signs of malignancies involving the lymphatic system and blood

5. Describe prevention strategies for Lyme disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus

6. Determine and understand diabetic emergencies

7. Recognize and refer those with signs and symptoms of a malfunctioning thyroid

Introduction

Because the discussion of systemic conditions covers all body systems, the organization of this chapter differs slightly from that of other chapters. The chapter begins with a review of the anatomy and physiology of the lymphatic system. The anatomy and physiology of the respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, gynecological, and neurological systems have already been discussed, and the integumentary and musculoskeletal systems are covered in Chapters 16 and 17.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Lymphatic System

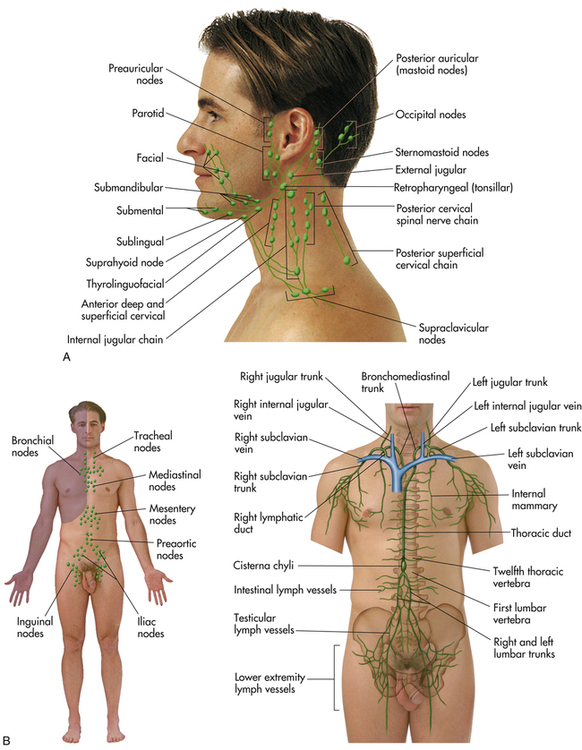

The anatomy and physiology of the lymphatic system are discussed because it is a facilitator for the spread of some pathological conditions, especially the lymphomas discussed below. The role of the lymphatic system is to maintain internal fluid balance and assist with immune functions in the body. It is a collection of vessels, ducts, nodes, organs, and tissue that transports fats, proteins, and lymphatic fluid throughout the body (Figure 14-1). The system restores the majority of the fluid that filters out of the blood during normal homeostasis. It performs this function by collecting fluid that leaks from capillaries into surrounding tissues, and returns it to the blood. The lymphatic system consists of lymph nodes, organs (spleen, thymus, and tonsils), and vessels that parallel veins. The lymph nodes are home to lymphocytes (T cells and B cells), the white blood cells that are largely responsible for producing antibodies to combat infections. A healthy node is typically round or kidney-shaped and up to 1 inch in diameter. Nodes cluster in the cervical region, axilla, and groin. Infections in these regions produce swollen nodes, which become enlarged and tender to palpation as the macrophage cells fight invading cells. In addition to actual structures, there are numerous areas in the body that support lymph tissue, such as bone marrow, the intestines, liver, skin, heart, and lungs.

Pathological Disorders

Malignancies

Cancer is another name for all malignant entities, especially carcinomas and sarcomas. As a group, cancers represent the second leading cause of death in adults.1 By their nature, malignant cells migrate to adjacent tissues, or use the blood or lymph to transport cells to distant regions of the body.

Lymphatic Malignancies

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is a group of malignancies of the lymphoreticular system. The lymphoreticular system is a collection of lymphoid tissues formed by several types of immune system cells from both the lymph and reticuloendothelial systems that fight primarily against infection. There are several types of NHL as well as several different classifications. The median age for diagnosis with NHL is 50 years, and the incidence increases with age. Estimates of approximately 65,000 new cases of NHL during 2009 in the United States have been reported, and approximately 19,500 of those patients died of the disease.1 It is typically among the top six cancers diagnosed in the United States and holds the same ranking for cancer-related deaths.1

Signs and Symptoms

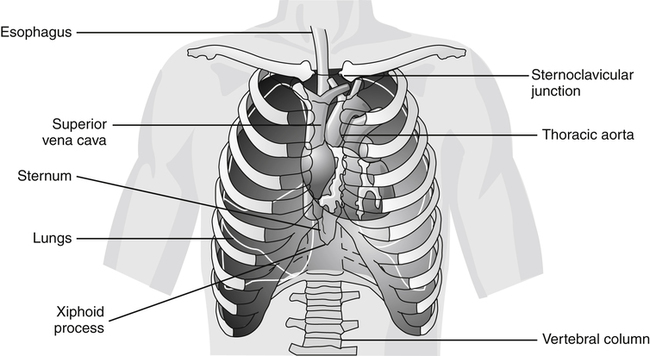

Because NHL is a group of lymphatic cancers, patients can present with a variety of symptoms depending on the site affected. The most frequent sites are the abdomen, mediastinum, and neck. If the abdomen is affected, the patient can experience nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, usually accompanied by abdominal pain and weight loss. The patient may also have an enlarged spleen or liver or a palpable mass in the abdomen. Other general signs include excessive sweating, including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, and unexplained fevers. When the mediastinum is affected, the disease generally progresses more rapidly. Presenting symptoms can range from chest pain to severe shortness of breath on exertion. Neck masses and enlarged lymph nodes can also present as NHL. Figure 14–1, A shows the location of specific cervical lymph nodes.

Referral, Diagnostic Tests, and Differential Diagnosis

Athletes who have enlarged lymph nodes without apparent cause (e.g., infection distal to the gland), inexplicable chest pain, or dyspnea should be referred to a physician for further evaluation. When NHL is suspected, imaging by computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound can help confirm the presence and size of the affected lymph nodes. The diagnosis is confirmed by sampling of tissue from the enlarged lymph nodes by fine-needle biopsy or removal of the affected lymph node with subsequent analysis by pathologists. If the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, referral to an oncologist should be initiated for specific treatment.

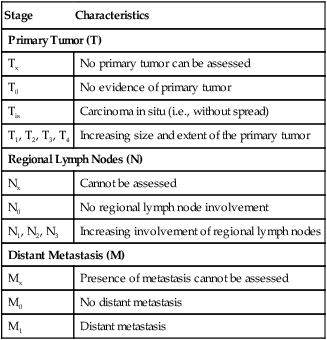

Patients suspected of having NHL will undergo a complete history and physical examination followed by laboratory work. Initially, patients may present with mild anemia and an elevation of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).2 A battery of other blood tests is performed to help stage the disease. The cancer staging is accompanied by CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis to assess for spread of the disease (Table 14-1). Other tests can be performed depending on the initial findings.

TABLE 14-1

TNM System for Cancer Staging∗

| Stage | Characteristics |

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| Tx | No primary tumor can be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ (i.e., without spread) |

| T1, T2, T3, T4 | Increasing size and extent of the primary tumor |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| Nx | Cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node involvement |

| N1, N2, N3 | Increasing involvement of regional lymph nodes |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| Mx | Presence of metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

∗The universally accepted TNM system for cancer staging helps to determine the extent or spread of the disease in order to establish treatment decisions and prognosis for recovery. It groups cancers into one of four stages (I to IV) or stage 0 for carcinoma in situ, which means without spread. Higher stages such as stage IV or M4 represent distant metastasis and the worst prognosis.

Treatment, Prognosis, and Return to Participation

Prognosis varies widely and depends on the stage, size, and histological type of the disease. Patients with low-grade lymphoma, despite long-term survival of 6 to 10 years,3 are rarely cured and usually die of lymphoma. Those patients with high-grade or metastasized NHL tend to do better and may achieve a cure with aggressive chemotherapy. The success rate for cure in this case is 35% to 50%.

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

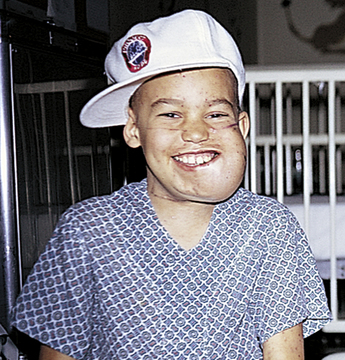

Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a malignant disorder of lymphoreticular origin, different histologically from NHL because of the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells (multinucleated giant cells).3 The incidence of the disease increases throughout childhood and into the late teenage years,2 but peaks from age 25 to 30 years. Hodgkin’s disease is rare in children under the age of 5 years, and children 16 years and under account for 10% to15% of the disease. The overall incidence is 4 per 100,000. A second peak in incidence occurs among people 55 years of age and older. The disease is more common among Caucasians, higher socioeconomic groups, and males; of teens with Hodgkin’s, 80% are male.3

Signs and Symptoms

Although Hodgkin’s lymphoma has several possible presenting signs, the most common initial sign is an enlarged lymph node, typically in the lower anterior neck region. It is usually nontender, discrete, firm, and rubbery; is not fixed to adjacent structures; and can vary in size.4 Patients with mediastinal chest involvement can present with shortness of breath, chest pain, or cough. On occasion, enlarged lymph nodes are present in the axillary or inguinal region; Figure 14-2 illustrates the most common sites of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Intense itching and intermittent fevers associated with night sweats are classical symptoms of this disease. Roughly 25% of patients will present with systemic symptoms, including fatigue, fever, weight loss, and night sweats.5

Referral, Diagnostic Tests, and Differential Diagnosis

Athletes with persistent neck masses (Figure 14-3) or constitutional symptoms such as night sweats, intermittent fevers, and a weight loss greater than 10% of total body weight should be evaluated by a physician. If the diagnosis is confirmed, referral to an oncologist is appropriate for further treatment.

Treatment, Prognosis, and Return to Participation

Treatment revolves around the histological diagnosis as well as the staging, but Hodgkin’s lymphoma generally requires radiation therapy as well as chemotherapy. With advances in chemotherapy, Hodgkin’s disease can be cured in most patients with both localized and advanced disease.5 Surgery may be indicated if the disease is extensive.

The overall survival rate for Hodgkin’s disease is 60% to 99% at 10 years, depending on the type and involvement.1 A decision regarding return to competition is made by the athlete’s physician, and competition is best avoided during the acute illness as well as during the treatment phase.

Leukemia

The several different types of leukemias have different treatments and prognoses. In general, leukemias are characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of white blood cells in the bone marrow, which accumulate and replace normal blood cells in the marrow. It can then spread to different parts of the body, including the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and central nervous system. Cancers that start from other places and then spread to the bone marrow are not leukemias. It was thought at one time that lymphomas arose only from the lymphatic system, and leukemias from bone marrow, and that these two malignancies were distinctly different. This is no longer supported, as the differentiation between these two is often vague.6

Nearly 45,000 cases of all types of leukemia are diagnosed in the United States annually.1 Leukemia is among the top 10 types of cancer in the adults, but it is the most common malignancy in children. In adults, the most common leukemias are acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).7 Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is about half as common as CLL, affects mostly adults, and is very rare in children. Children, especially between the ages of 1 and 19 years, are most likely to develop acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).1,2 Leukemia is more common in Caucasians and males, but there is an increasing incidence of AML in African-American men.7

Referral and Diagnostic Tests

Several different findings evident on a CBC are helpful in the diagnosis of leukemia. Patients can have a very low (<5000/mm3) or very high (>100,000/mm3) white blood cell count. See Table 3-3 for normal blood values. The CBC may also reveal a low platelet count or anemia, which would explain easy bruising and fatigue, respectively. The key for identifying the type of leukemia is a peripheral blood smear or a bone marrow biopsy, which will show the type of abnormal white blood cells that predominate. Other abnormal laboratory findings include elevated LDH and uric acid levels. Chest radiographs are routinely performed to rule out mediastinal masses. CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or ultrasound of the abdomen is used to check for hepatomegaly or splenomegaly.2

Prognosis and Return to Participation

For ALL, the prognosis is much better in children (88% survival rate) than in adults (66%).1 Remission can be achieved in AML in 80% of patients younger than 55 years of age. The remission rates in children are even higher. In CLL, the prognosis is related to the stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis. When the disease is caught early, average survival is nearly 10 years; when the disease is caught late, average survival can be only 2 years. The overall 5-year survival for CLL is 76%.1

Vector-borne Disease

A vector-borne disease is one that is carried by an infected organism (i.e., a tick or mosquito) to a healthy individual. This group of diseases is largely preventable by avoiding the habitats where these organisms live or by applying repellent. See Box 15-4 for the relationship among vector-borne diseases, carriers, and their hosts.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease, the most common tick-borne illness in the United States, was first described in the late 1970s in Lyme, Connecticut. It is a multisystem disorder that, when left untreated, can lead to serious arthritic and neurological symptoms that become increasingly difficult to treat because of permanent tissue damage.8 The culprit responsible for Lyme disease is Borrelia burgdorferi, a spirochetal bacterium that is transmitted to humans from infected ticks.

People most affected by Lyme disease are those who spend a large amount of time outdoors and are bitten by ticks between May and September (Figure 14-4). Ninety-three percent of cases arise from 10 states (Box 14-1). In 2008, an estimated 35,000 infections were reported the United States.9

Signs and Symptoms

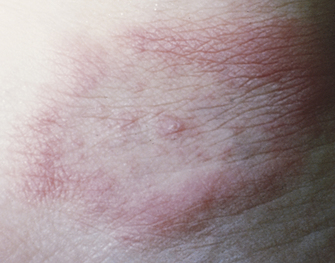

Lyme disease can be broken down into three different categories based on the longevity of symptoms. In 70% to 80% of patients, early localized Lyme disease begins as a red, circular rash called erythema migrans that enlarges over days (Figure 14-5). This rash, which can stretch to 12 inches (30 cm), can appear anywhere from 3 to 30 days after a tick bite and generally occurs on the trunk of the body.9 The rash is usually accompanied by a viral-like illness, with symptoms that can include headaches, muscle aches, fevers, joint aches, fatigue, and occasionally a stiff neck. Fewer than 20% recall being bitten by a tick.8

Disease that is not treated at the onset of the rash can lead to early disseminated Lyme disease within weeks to months. Patients may present with facial nerve palsies or even meningitis in 10% of cases.10 Patients who develop lymphocytic meningitis generally have only neck pain and stiffness, but they may not have the typical findings associated with meningitis on physical examination, such as positive Brudzinski’s and Kernig’s signs (see Figures 15-4 and 15-5).

The diagnosis of Lyme disease that has spread to he nervous system is confirmed by testing spinal fluid taken by means of a lumbar puncture (see Box 15-6). Early disseminated Lyme disease can also present with cardiac manifestations occurring anywhere from 1 week to 7 months after the bite and peaking at 1 to 2 months. Affected patients may have a variety of symptoms, including chest pain, palpitations, weakness, fatigue, or shortness of breath. The cause of these symptoms can be a conduction abnormality in the heart, leading to irregular rhythms or abnormal findings on an electrocardiogram. The heart muscle may also become inflamed because of infection of the heart tissue.

Late Lyme disease is characterized by manifestations involving the musculoskeletal system or central nervous system. Patients may experience intermittent attacks of brief swelling of the joints followed by chronic pain and arthritic changes. This can occur from weeks to years after the initial tick bite, and its incidence approaches 50% among those who were untreated at the time of infection.8 Tertiary neuroborreliosis is the name given to a syndrome of progressively worsening cognitive function, which is thought to be caused by infection of the central nervous system by B. burgdorferi, the spirochete that is passed on from the infected tick.

Referral and Diagnostic Tests

Despite this information, routine serological testing of those with erythema migrans is not recommended because only one third of those patients with a single lesion will test positive. If several erythema migrans lesions are noted, the number of positive tests jumps to 90%.10 Those persons with suspected Lyme disease without the rash should have samples taken immediately with repeated sampling in 4 to 6 weeks. Regardless of the laboratory outcomes, if the symptoms are consistent with Lyme disease, treatment needs to be initiated.

If the athlete has a clinical history of a tick bite and central nervous system manifestations or a swollen joint, fluid from the affected area should be taken for analysis. The clinician should remember that all swollen joints are not necessarily caused by trauma or injury, and if the suspicion is high, Lyme arthritis needs to be ruled out to ensure appropriate treatment.11

Treatment

Early treatment of Lyme disease usually prevents any of the aforementioned complications. For early disease, oral antibiotics, including doxycycline or amoxicillin, are used in a 10- to 21-day course.8,12 Cases diagnosed later or that involve the central nervous or cardiac systems typically require intravenous antibiotics. Giving antibiotics to symptom-free people who have been bitten by ticks has not been proven to lessen the incidence of the disease. The current recommendation is to monitor closely those bitten by ticks for findings of Lyme disease, including erythema migrans, and to treat those infected appropriately.

Prognosis, Return to Participation, and Prevention

With appropriate and expeditious treatment of Lyme disease, major late sequelae of the disease can be prevented, including nervous system manifestations, carditis, and recurrent arthritis.8

Primary prevention is obviously avoidance of ticks; wearing proper clothing, including long pants tucked into socks; using insect repellent; and routine inspection for ticks after possible exposure. Insect repellent containing the compound N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (DEET) has been shown to be especially helpful in deterring ticks.13 Early removal of ticks is essential (Box 14-2) because transmission of B. burgdorferi is rare unless the tick has been attached to the human host for more than 48 hours.3 After marketing a vaccine for 4 years, from 1998 to the beginning of 2002, the manufacturer (GlaxoSmithKline) announced that it would no longer be commercially available.3

Chronic Disorders

Raynaud’s Disease

Raynaud’s disease is a disorder characterized by vasospasm of the arteries, primarily in the hands, but it can also affect the feet, nose, and ears. Stressors, including cold temperatures and emotional trauma, exacerbate the disease. The two presentations of Raynaud’s disease are primary and secondary. Typically, the primary condition is referred to as Raynaud’s disease if no other cause can be found. Secondary Raynaud’s is caused by an underlying problem and is termed Raynaud’s phenomenon. The numerous causes for Raynaud’s phenomenon include medications such as oral contraceptives, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and tools that cause vibration (Box 14-3).3

Signs and Symptoms

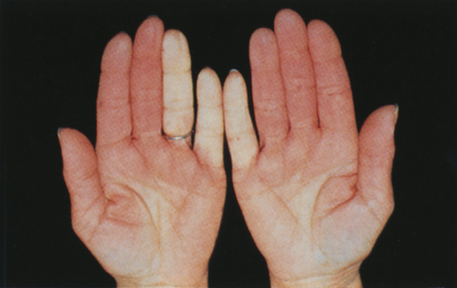

Patients typically present with a triphasic color response to cold exposure:

1. Pallor: The skin, most often of the fingers, will become pale, or pallid, because of vasospasm (Figure 14-6).

2. Cyanosis: The skin will then become blue, because of the increase in venous, or deoxygenated, blood in the digits.

3. Erythema: The skin turns red when the vasospasm resolves and a rush of blood enters the digits, causing pain and numbness.

As noted previously, these symptoms can happen in the hands, feet, nose, and ears and usually occur bilaterally. The symptoms generally resolve over minutes, but if they persist, they can lead to ulcerations, gangrene, and dead tissue.3

Referral, Diagnostic Tests, and Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of Raynaud’s phenomenon includes those secondary causes listed previously, as well as CREST syndrome (calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysfunction, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia), scleroderma, carpal tunnel syndrome, and Buerger’s disease.3

Treatment

The simplest of treatments is avoidance of the triggers that propagate Raynaud’s, such as avoiding medications that may cause it, staying out of the cold, wearing appropriate protective clothing (Figure 14-7), and avoiding other triggers such as caffeine and tobacco.3 For those with no relief from the nonpharmacological approach, medications can be used to decrease symptoms. Calcium channel blockers, such as nifedipine, have proven to be the most effective treatment for Raynaud’s disease. Other medications that have proven helpful include α-blockers and to a lesser extent aspirin and topical nitrates.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree