Site

Effect

Epiphyseal

Joint pathologies

Short stature

Metaphyseal, diaphyseal

Short, deformed long bones

Spondylodysplasis

Cervical instability

Kyphoscoliosis

Descriptions can be based on the specific site of limb shortening (see Fig. 14.1):

Figure 14.1

Anatomic description of skeletal dysplasias

Proximal segment: Rhizomelic.

Middle segment: Mesomelic.

Distal segment: Acromelic.

Other terms used to describe deformities include:

Diastrophic = twisted.

Camptomelia = bent.

Metatrophic = changing.

Thanatophoric = fatal in the neonatal period.

Platyspondyly = flat vertebrae.

Achondroplasia = short-limbed.

It is important to remember that the term dwarfism is no longer in use, and instead the deformity can be described as a short stature.

Classification

Classifying skeletal dysplasias is similarly difficult owing to the variety in types. Possible classifcations systems include:

Clinical

Proportionate: Limb length is approximately the same length as the trunk. This is commonly associated with medical or endocrine conditions such as Turner’s syndrome. Two main groups of disorders exist:

Cleidocranial dysplasia – recognizable clinical features such as frontal bossing and short middle phalanges, along with absent or partially missing clavicles.

Mucopolysaccharidoses – Recognised through positive complex sugars in the urine.

Disproportionate: In general these disorders lead to either a short trunk with normal size limbs (e.g. achondroplasia) or short limbs with a normal size trunk (e.g. Morquio’s).

Disproportionate short trunk skeletal dysplasias:

Kneist’s dysplasia: associated with a cleft palate deformity and deafness.

Spondyloepiphseal dysplasias: accompanied by spinal deformities.

Disproportionate short limb skeletal dysplasias:

Achondroplasia: associated with particular facial features, e.g. a large head, frontal bossing, a small midface and flattened nasal bridge.

Multiple Epiphyseal Dysplasia: without facial involvement.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI): altered bone density.

Multiple hereditary exostoses: associated with multiple osteochondromas.

Radiological

Bone region affected (see Table 14.1).

Bone density:

Osteopenia.

Osteoporosis.

Individual structural irregularities:

Skull – Wormiam bone in OI.

Hypoplastic clavicles (cleidocranial dystosis).

Molecular/genetic

The majority of skeletal dysplasias can be accounted for by abnormalities in 11 different gene mutation families or broadly characterized in four groups:

Defects in the structural protein of cartilage: collagen/ cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP).

Errors in local regulators of cartilage growth: Fibroblast growth receptor, parathyroid hormone related peptide receptor, cell surface heparin sulphate receptor (EXT).

Errors in cartilage metabolism: Diastrophic Dysplasia Sulphate Transporter.

Systemic defects influencing cartilage development: lysosomal enzymes.

Mendelian inheritance

The majority are autosomal dominant, e.g. Achondroplasia (Fig. 14.2).

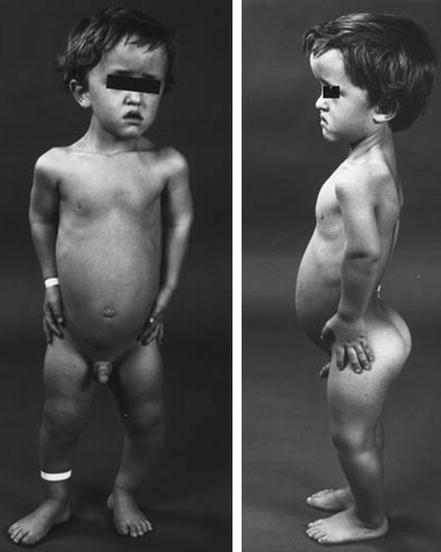

Figure 14.2

Achondroplasia. Note the characteristic features described above (Reproduced from Benson et al. Children’s Orthopaedics and Fractures, 2009, Springer)

Autosomal recessive, including some forms of osteogenesis imperfecta or multiple epiphyseal dysplasia.

X-linked, e.g. Hunter’s type II MPS.

Diagnosis of Skeletal Dysplasias

Skeletal dysplasias may be diagnosed during the prenatal period, at birth or during childhood. Prenatal diagnosis is predominantly based on the use of ultrasound examination. Despite being a common and routine perinatal assessment, the ultrasound diagnosis of skeletal dysplasia can be challenging due to the variable presentations of the pathology. Sonographers must have a high index of suspicion when a family history is present. Subtle features that may suggest the presence of a dysplasia include:

Unequal bone lengths.

Absence, hypoplasia or malformation of bones.

Abnormal chest circumference and cardiothoracic ratio.

The presence of polydactyly, syndactyly, clinodactyly or any other extremity deformity (see Chap. 4 Hands).

Abnormal foot length.

Abnormal head circumference and biparietal diameter.

The presence of abnormal spinal curvatures (see Chap. 5 Scoliosis).

Unusual pelvic geometry.

Several factors from the parental history and features at birth may aid the diagnosis, or raise suspicion, of a skeletal dysplasia. Such features include:

Positive family history.

Maternal age.

Previous stillbirth.

Low or high birth weight.

Length of child.

Arm span.

Head circumference.

Associated congenital malformations, e.g. laryngomalacia, tracheomalacia or bronchomalacia.

Maternal use of certain medications during pregnancy, e.g. warfarin, which may cause stippled epiphyses.

Skeletal dysplasia may present late, during childhood, with features such as short stature or inappropriate upper/lower segment ratio. Similarly associated abnormalities may prompt a diagnosis, such as hearing and/or visual impairment or connective tissue abnormalities. A radiological assessment at late presentation should include full a skeletal survey and a measurement of bone density. Laboratory tests should include:

Calcium.

Phosphate.

Albumin.

Alkaline phosphatase.

Parathyroid hormone.

Vitamin D.

Other useful investigations include cytogenetic tests, to assess chromosomal deletions or rearrangements, molecular genetic testing and biochemical testing.

Common Orthopaedic Problems Associated with Skeletal Dysplasia

Spinal disorders: the common spinal disorders that are associated with skeletal dyplasias are:

Thoracolumbar kyphosis (70%).

Scoliosis (25%).

Atlantoaxial instability/cervical kyphosis (15%).

Spinal Stenosis.

Neurological complications associated with such spinal deformities may produce the following clinical features:

Gait deterioration.

Deterioration of neurological function, i.e. muscle fatigue and hyper-reflexia.

Limb disorders, including:

Joint deformity.

Limb malalignment.

Arthritis.

Soft tissue laxity.

Contractures.

Limb length discrepancy or overall shortening.