Fig. 7.1

Scapula – anterior (costal) aspect. 1 Trapezoid ligament attachment. 2 Conoid ligament attachment. 3 Acromion process. 4 Suprascapular notch. 5 Omohyoid (inferior belly). 6 Serratus anterior. 7 Subscapularis. 8 Ridge for intermuscular tendon of subscapularis. 9 Deltoid. 10 Biceps (short head) and coracobrachialis. 11 Pectoralis minor. 12 Glenoid fossa. 13 Triceps (long head) (Modified with permission from Grays Anatomy, 39th Edition, Strandring, S. Figure 49.4 Copyright Elsevier, 2005)

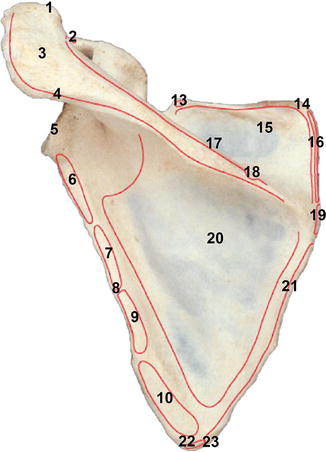

Fig. 7.2

Scapula – posterior (dorsal) aspect. 1 Clavicular facet. 2 Biceps (short head). 3 Acromion. 4 Deltoid. 5 Glenoid fossa. 6 Triceps brachii (long head). 7 Teres minor. 8 Groove for circumflex scapular artery. 9 Teres minor. 10 Teres major. 11 Conoid tubercle. 12 Coracoid process. 13 Omohyoid (inferior belly). 14 Superior angle. 15 Supraspinatus. 16 Levator scapulae. 17 Spine. 18 Trapezius. 19 Rhomboid minor. 20 Infraspinatus. 21 Rhomboid major. 22 Latissimus dorsi. 23 Inferior angle (Modified with permission from Grays Anatomy, 39th Edition, Strandring, S. Figure 49.3 Copyright Elsevier, 2005)

Fig. 7.3

Scapula – viewed from lateral view. Superior aspect of left scapula. 1 Facet for clavicle. 2 Acromial process. 3 Spine. 4 Superior border. 5 Head. 6 Glenoid fossa. 7 Neck. 8 Conoid tubercle (for conoid ligament). 9 Coracoid process. 10 Trapezoid ligament attachment (Modified with permission from Grays Anatomy, 39th Edition, Strandring, S. Figure 49.5 Copyright Elsevier, 2005)

7.2 Muscles and Tendons

Numerous muscles insert or originate at the scapula. Along the medial margin from superior to inferior insert the levator scapulae, the minor and major rhomboid. Most of the costal face (Fig. 7.1) gives the origin to the subscapularis muscle. On the costal face all along the medial margin and at the inferior angle insert the serratus anterior.

On the dorsal face (Fig. 7.2) along the lateral margin originate from superior to inferior the triceps, the teres minor and the teres major muscles. Sometimes also a few fibres of the latissimus dorsi insert at the tip of the inferior angle.

The long head of the triceps has its fibres partly attached to the distinct infraglenoid tubercle, a part of the inferior glenoid, and the inferior labrum, partly woven into the joint capsule and partly to the adjacent bone.

The dorsal face of the scapula is divided in two by the spine, below originates the infraspinatus muscle, and above the supraspinatus.

The trapezius muscle inserts with its upper part on the lateral two thirds of the clavicle, with its middle part on the acromion and scapular spine, and with its lower part at the base of the scapular spine. The deltoid muscle originates with its middle part on the acromion and its posterior part along the scapular spine.

At the superior margin, on the costal face just medial to the suprascapular notch is the origin to the omohyoid muscle, an important landmark for brachial plexus and cervical dissections. At the lateral angle of the scapula, anterior on the top of the glenoid originates the long head of the biceps.

7.3 Ligaments

Several ligaments attach to the scapula. Two of them, the coracoacromial ligament and the transverse scapular ligament, are special in the way that they attach to the same bone on both sides (Fig. 7.3). The transverse scapular ligament traverses the scapular notch and separates the underlying suprascapular nerve from the artery with the same name that runs cranial to the ligament. The shape of the notch shows great variability and that is also the case for this ligament that may be long or short, wide or thin, even split with the nerve in between in some cases (See Chap. 33). The ligament may ossify, and thus, become a foramen instead of a notch.

An inferior transverse scapular ligament has been reported in rare cases, running across the spinoglenoid notch.

The other scapular ligaments; the acromioclavicular ligament, the coracoclavicular ligaments, the coracohumeral ligaments and the glenohumeral ligaments will be described in different chapters.

7.4 Articulations

The scapula has two true articulations, the acromio-clavicular joint with the articular surface on the anteromedial aspect of the acromion, and the glenohumeral joint at the lateral angle [1, 2].

Considerable motion takes place between the scapula and the thoracic wall, the scapula gliding on the wall with only a bursa to assist in reducing the resistance.

7.5 Biomechanics and Function

The body of the scapula offers a mobile fixation point for the proximal upper extremity muscles. This means that scapulothoracic motion allows, among others, the deltoid muscle to remain in optimum position for effective contraction throughout the arch of arm elevation.

Motion of the upper extremity consists of a combined motion of the glenohumeral and the scapulothoracic joints. The relative contribution of each of these complex motion patterns in the total achieved varies with the position of the arm and also shows considerable variations between individuals and even by sex. Summarized, in the early phases of arm elevation a variably larger proportion occurs in the glenohumeral joint, whereas the last 60° occurs with about equal contribution of the two joints [3], It is generally accepted that the overall contribution of the glenohumeral to the scapulothoracic joint is a two-to-one relationship.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree