104 Relapsing Polychondritis

![]()

![]() Supplemental image available on the Expert Consult Premium Edition website.

Supplemental image available on the Expert Consult Premium Edition website.

Epidemiology

The worldwide incidence of RPC is unknown, but figures from Rochester, Minnesota, suggest an annual incidence of 3.5 per million in that community.1 RPC occurs in all racial groups and with similar frequency in men and women. Peak age of onset is 40 to 50 years, but it has been described in children and in people older than 80 years of age. No familial pattern of inheritance has been shown.

Pathology

Cartilage has a cellular component consisting of chondrocytes and an extracellular matrix made from interlinking fibrils of type II collagen, other collagens, hydrophilic proteoglycan aggregates, and a variety of matrix proteins.2 One such protein, matrilin-1, is exclusive to the respiratory tract, ears, and xiphisternum in adults and is only found in articular cartilage before skeletal maturity.3 Cartilage is an avascular structure that derives essential nutrients from adjacent tissue. The composition of cartilage confers resilience to external compressive forces. In normal adults, turnover of cartilage components is slow, with incomplete repair processes.4 Degradation of collagen fibrils occurs with age resulting from imbalances between naturally occurring proteolytic enzymes and their inhibitors.5

In RPC, typical features on hematoxylin-eosin staining include a loss of normal cartilage basophilia and a perichondrial inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and plasma cells.3,6 Necrosis and a reduction in cartilage components may be observed. The cartilage is subsequently replaced by fibrotic tissue.6 Immunofluorescence may demonstrate immunoglobulin and complement components in the perichondrial tissue and vessels.7

Pathogenesis

Although the pathogenesis of RPC is unknown, evidence supports the concept of an autoimmune process. Researchers have observed autoantibodies to types II, IX, and XI collagen in patients with this disease,3,8–10 while autoantibodies to matrilin-1 have been detected in those with respiratory tract involvement.11 Specific cytokines such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein 1β, and interleukin-8 are significantly elevated in active RPC compared with controls.12 Furthermore, there is a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II association with RPC. A twofold increase in HLA-DR4 has been found in RPC, although a specific subtype has not been identified.13

Several animal models have helped elucidate some of the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying RPC. Chondritis can be induced in certain rat or mice species following injection of type II collagen.14,15 In addition, mice expressing HLA-DQ6ab8ab transgenes develop a spontaneous form of polychondritis with auricular, nasal, and joint involvement.16 Experiments using the matrilin-1-induced rodent model of RPC have demonstrated the importance of T cells, B cells, and complement components in pathogenesis of this disease.17 Deletion of interleukin (IL)-10 in this model resulted in increased disease severity, suggesting a role for this endogenous cytokine in suppressing episodic inflammation.18

Clinical Features

The diagnostic criteria for RPC are outlined in Table 104-1. Table 104-2 documents the frequency of clinical presentations.

Table 104-1 Diagnostic Criteria

| Major Criteria |

| Minor Criteria |

| Diagnosis is made by two major criteria or one major plus two minor criteria. |

| Histologic examination of affected cartilage is not required. |

From Michet CJ Jr, McKenna CH, Luthra HS, et al: Relapsing polychondritis: survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations, Ann Intern Med 104:74–78, 1986.

Table 104-2 Clinical Features of Relapsing Polychondritis

| Clinical Feature | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| At Presentation | In Total | |

| Auricular chondritis | 39 | 85 |

| Nasal chondritis | 24 | 54 |

| Arthritis | 36 | 52 |

| Eye disease | 19 | 51 |

| Laryngotracheal bronchial disease | 26 | 48 |

| Hearing loss | 9 | 30 |

| Rash | 7 | 28 |

| Systemic vasculitis | 3 | 10 |

| Valvular dysfunction | 0 | 6 |

| Costochondritis | 2 | 2 |

Modified from Michet CJ, McKenna CH, Luthra HS, et al: Relapsing polychondritis: survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations, Ann Intern Med 104:74–78, 1986; and Gergely P, Poór G: Relapsing polychondritis, Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 18:723–738, 2004.

Otorhinologic Disease

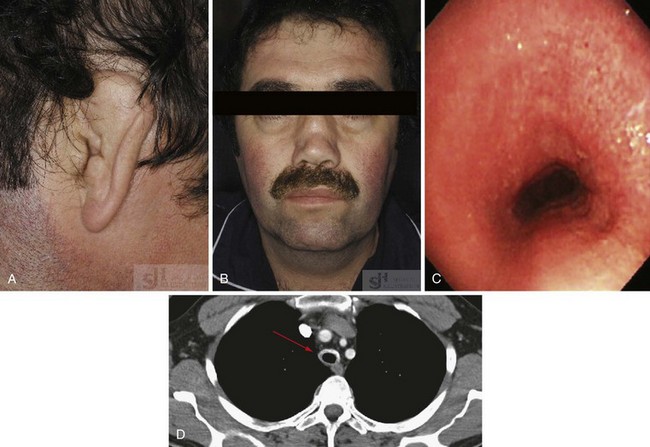

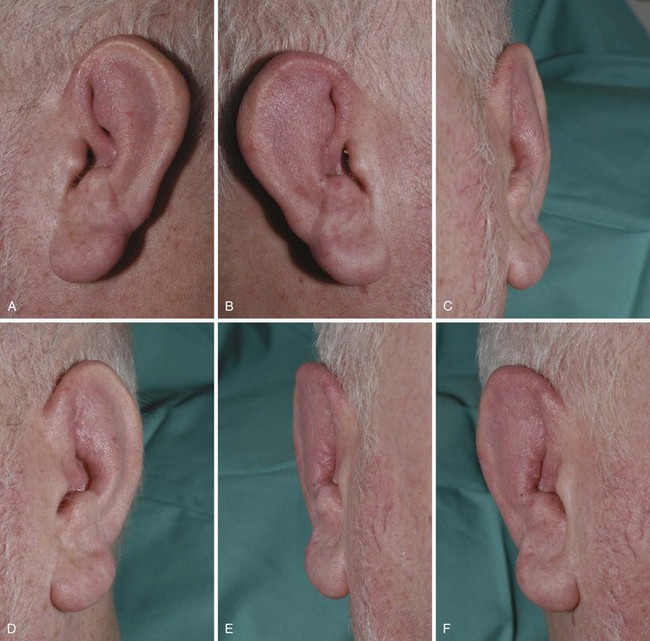

The most characteristic manifestation of RPC is auricular chondritis, in which the patient develops acute pain, redness, and swelling of the cartilaginous upper two-thirds of the outer ear, sparing the lobe19 (Supplemental Figure 104-1 on www.expertconsult.com). It may be unilateral or bilateral and resolves spontaneously over a period of several weeks. Repeated episodes result in visible damage to the ear, with a deformed, flaccid appearance (Figures 104-1A and 104-2). Although classic in RPC, it is the presenting feature in only 40%, whereas up to 85% of patients eventually develop this feature over the course of their disease.20 Such swelling of the outer ear causes temporary conductive deafness. However, sensory-neural deafness may result from an associated vasculitis of the internal auditory artery or its branches, leading to additional vertigo in some patients.6,19 A similar pattern of chondritis in the nose may cause collapse of the nasal bridge and an alteration of the facial appearance—the so-called saddle-nose deformity (Figure 104-1B).

Respiratory Disease

Involvement of the upper respiratory tract may be life threatening and should be investigated at an early stage in the disease course. Approximately 50% of patients with RPC develop respiratory problems, which are associated with a worse prognosis.21 Hoarseness, dysphonia, a persistent dry cough, or anterior neck tenderness may indicate laryngeal or tracheal disease. Inflammation of the tracheobronchial tree may lead to tracheomalacia, dynamic obstruction, and acute respiratory failure, whereas repeated inflammatory episodes cause subglottic stenosis, chronic dyspnea, and increased susceptibility to infection.22 Obstruction may be precipitated by attempts at intubation or bronchoscopy.6 Computed tomography and bronchoscopy appearances of one patient with RPC are demonstrated in Figure 104-1C and D. The development of costochondritis may result in chest pain, leading to additional respiratory symptomatology.

Cardiovascular Disease

Large and small vessel disease can occur during the course of RPC in up to 10% of cases.23 Inflammation of the aorta, most likely to occur at the level of the root or arch, leads to aneurysm formation and aortic incompetence, which may develop acutely with minimal prior symptoms.6,24 Aortic valve disease may be due to progressive dilatation of the aortic ring rather than to active local inflammation.6 Mitral regurgitation may result from valvitis or papillary muscle involvement, whereas myocarditis may lead to cardiac failure and conduction system abnormalities.1,22,23 Small vessel vasculitis has also been reported and may cause end-organ damage to the skin, kidneys, testes, sclera, cochleovestibular system, or other areas.6,25 Arterial and venous thromboses have been described in association with RPC.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree