102 Proliferative Bone Diseases

Proliferative bone diseases encompass a variety of conditions characterized by exuberant bone and entheseal ossifications and calcifications. New bone formation is the main feature in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA) and is a common finding in osteoarthritis. New bone formation may also accompany some spondyloarthropathies such as ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and sternoclavicular syndrome, also known as SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteomyelitis). New bone formation has also been described in endocrine diseases, however, such as thyroid disorders, acromegaly, and hypoparathyroidism (Table 102-1).1–3 Osteoarthritis, spondyloarthropathies, and endocrine disorders are discussed elsewhere in this book.

Table 102-1 Proliferative Bone Diseases

SAPHO, synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteomyelitis.

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

DISH is a condition characterized by calcification and ossification of soft tissues, mainly ligaments and entheses. This condition was described by Forestier and Rotes-Querol in 19504 and was termed senile ankylosing hyperostosis. There is a marked predilection to the axial skeleton, particularly the thoracic spine. Recognition that the condition is not limited to the spine and may involve peripheral joints led researchers to coin the name DISH, a term now widely used.5

DISH is characterized by the production of coarse, flowing osteophytes involving, in particular, the right side of the thoracic spine with preservation of the intervertebral disk space and by ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament. Calcification and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament seem to be additional skeletal manifestations of DISH. Other entheseal regions might be affected such as the peripatellar ligaments, Achilles tendon insertion, plantar fascia, olecranon, and others.6–8

The diagnosis is usually based on the definition suggested by Resnick and Niwayama.5 This radiographic approach requires the presence of flowing, coarse osteophytes on the right side of the thoracic spine, connecting at least four contiguous vertebrae, or ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament, preserved intervertebral disk height in the involved segment, and the absence of apophyseal joint ankylosis and sacroiliac joint involvement (Table 102-2).8 Another set of criteria, for epidemiologic purposes, was suggested by Utsinger.7 These criteria consider also peripheral enthesopathies. A definite diagnosis of DISH is established by criteria similar to those suggested by Resnick and Niwayama. A probable diagnosis of DISH is possible, however, with continuous ossification or calcification, or both, of the anterolateral aspect of at least two contiguous vertebral bodies and bilateral well-corticated enthesopathies in the heel, olecranon, and patella. It has also been suggested that peripheral enthesopathies might represent early DISH, which may evolve, over time, to its full radiologic appearance.

Table 102-2 Suggested Diagnostic Criteria for Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

Epidemiology

DISH is more common in men than women. An autopsy study reported that in a series of 75 spines studied at autopsy, 28% had DISH.9 The reported prevalence of DISH varies according to age, ethnic origin, geographic location, and clinical setting (i.e., hospital based versus population based). In a study of a North American metropolitan hospital population, the prevalence in men and women older than 50 years of age was reported to be 25% and 15%, respectively, and the prevalence in men and women older than 70 years was 35% and 26%, respectively.10 Similar figures were reported for patients from Budapest.11 Higher figures were reported for Jews older than 40 years living in Jerusalem, reaching a prevalence of 46% for men older than 80.12 A much smaller prevalence was reported from Korea, barely reaching 9% in the older age group.13 Native Africans had a prevalence of 13.6% in patients older than 70 years of age with no difference between men and women.14 In population-based, as opposed to hospital-based, studies, the reported prevalence was slightly greater than 10% in patients older than 70 years of age.15 Mild DISH was found in human remains dating back 4000 years. In human remains from the 6th to 8th centuries, the prevalence of DISH was higher in men than in women, reaching 3.7%. Although these studies were performed on different and relatively young populations, it seems that the prevalence of DISH is increasing.16,17

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology of DISH is unknown. Several metabolic, genetic, and constitutional factors were reported to be associated with this condition, however, including obesity, a high waist circumference ratio, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperinsulinemia, dyslipidemia, elevated growth hormone levels, elevated insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, hyperuricemia, use of retinoids, and genetic factors (Table 102-3).18–26

Table 102-3 Conditions Associated with Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

The association of DISH with excess body weight has been well known since the early descriptions by Forestier and others.9,27 This association was reiterated in a study in which patients with DISH were compared with healthy individuals and patients with spondylosis.28 The association of DISH with diabetes mellitus was reported in several studies.23,26 It was reported more recently that the prevalence of DISH is no higher in diabetic patients than in nondiabetic subjects, suggesting re-evaluation of diabetes as a risk factor for the development of DISH.29 More often, DISH was reported to be associated with more complex metabolic and endocrine derangements, with or without overt type II diabetes mellitus, comprising glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinemia, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, and elevated levels of growth hormone and IGF-I.19–2022 Due to these metabolic abnormalities, patients with DISH have a higher likelihood to be affected by metabolic syndrome and are subjected to a higher coronary artery disease risk.30

Hyperinsulinemia has a profound effect on ligaments and entheses, which is independent of age and obesity. The differentiation of mesenchymal cells in ligaments into chondrocytes and the subsequent endochondral ossification is promoted by insulin.24 The enthesis provides the growth plate for tendons and ligaments in children and persists into adulthood. This particular structure is composed of collagen fibers, fibroblasts, chondrocytes, and calcified matrix, which is probably a target for the ossification process promoted by insulin.18 Bone morphogenetic protein-2 is a potent osteogenic factor that promotes differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts and chondroblasts. It stimulates cell proliferation, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, and collagen synthesis.31 Its ability to promote mineralization is inhibited by matrix Gla protein, which is highly expressed in bone and cartilage. Matrix Gla protein deficiency or its altered carboxylation may cause a high level of bone morphogenetic protein-2 activity that leads to hyperostosis.26

The enthesis may also be under the influence of other growth-promoting peptides. Elevated growth hormone levels were reported in DISH. Growth hormone is capable of inducing osteoblast cell proliferation and may promote local production of IGF-I, which mediates the action of growth hormone and can stimulate ALP activity in osteoblasts.19,26,32,33 ALP promotes the calcification process during bone formation and is considered a good indicator for the maturation stages of osteoblasts.34,35 There is no explanation yet as to why the new bone formation is localized mainly at the ligamentous and entheseal sites. In male DISH patients, growth hormone serum levels were not elevated in the serum but were much higher in the synovial fluid.36 In the spine, vertebral blood supply could be a factor in the onset or progression of DISH.37 Intraerythrocyte growth hormone levels may exceed serum growth hormone levels and could be transported to the vertebral site by the mechanism described by Denko and colleagues.36

The expression of various genes involved in cell division and growth is regulated by nuclear factor κB (NFκB), which is capable of regulating the differentiation of multipotential cells. It was shown that activation of environmental factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 in ligament cells stimulates the activation of NFκB, which influences the osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal cells. This event is accompanied by elevation of ALP activity in cells of patients with DISH and serves as an indicator of maturation stages of the osteoblast.34 Inflammatory cytokines such as PDGF-BB, TGF-β1, and others may be related to the onset of non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and may be the link between this condition and the occurrence of DISH.38,39

Vitamin A and its derivatives have been implicated in the pathogenesis of DISH owing to their ability to promote new bone formation. Levels of vitamin A were reported to be higher in patients with DISH compared with controls, and some reports showed DISH-like manifestations in young patients treated with vitamin A or its derivatives.20,40 The role of vitamin A is unclear, however, because more recent studies did not show an increased prevalence of DISH among patients treated with vitamin A in various dosages and for various lengths of time.22,25,28 Larger prospective studies are necessary to elucidate the role played by this vitamin in the pathogenesis of DISH.

Familial clustering of DISH or families with early presentation of DISH suggest a genetic background for this disorder.41,42 Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament is closely related to DISH, and the two conditions can coexist. COL6A1, which is the candidate gene for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, was reported to be significantly associated with DISH in Japanese, but not in Czech, patients.43,44 This finding would suggest that other factors might play an important role in the genetic predisposition for the development of DISH.

There are no convincing explanations for the predilection of the hyperostotic process to affect the anterolateral aspect of the thoracic spine. The limited range of motion of the thoracic spine has been cited as a possible cause for the predilection to this site. This assumption cannot explain the involvement of the extremely mobile cervical spine or the lumbar spine, however. The less frequent involvement of the left side of the thoracic spine was ascribed to the pulsation of the aorta. This assumption was based on a few reports that described left-sided bridging osteophytes in cases with a right-sided aorta, suggesting that the aortic pulsations interfere with the production of the osteophytes.45 Calcifications, ossification, and subsequent stiffening of ligaments and joint capsules have important pathogenetic implications.

Osteoarthritis may have pathogenetic features in common with the peripheral joint manifestations of DISH. It was suggested that in the small non–weight-bearing joints in osteoarthritis, the process is caused by an increased intra-articular pressure and subsequent development of “crash” forces.46 This development was attributed to thickening of the collateral ligaments of these joints that enforce a constraint movement, not to primary damage to the cartilage. It seems reasonable that the joints affected by DISH may develop the same “crash” forces operating in small osteoarthritis joints, as a result of this mechanism. This mechanism might explain the involvement of “atypical” joints, not commonly affected by osteoarthritis, and the hypertrophic osteoarthritic changes in the commonly affected joints.

Clinical Manifestations

The lack of specific symptoms and signs of DISH, as well as the radiographic diagnostic criteria, have raised doubts about DISH as a separate entity.47 Although the disease may be asymptomatic, it was reported to be associated with morning stiffness, dorsolumbar pain, and reduced range of motion in most patients.7,8 Patients with DISH may have extremity pain involving peripheral large and small joints and peripheral entheses such as the heel, Achilles tendon, shoulder, patella, and olecranon. Pain in the axial skeleton may involve all three segments of the spine and the costosternal and sternoclavicular joints. The level of pain and disability is significantly higher compared with healthy subjects but is not different from patients with spondylosis.28 Complaints of pain referable to the thoracic spine are common and are accompanied by a reduced chest expansion.

Although similar in some aspects to osteoarthritis of the spine, DISH is a distinct clinical entity with different characteristics.48 Classically, the portions of the spine that are involved in osteoarthritis are the lower portions of the cervical spine and the lumbar spine. Thoracic spine involvement is uncommon in osteoarthritis or occurs in late stages of the disease, as opposed to the common involvement of the thoracic spine in DISH. Thoracic spine involvement in DISH is characterized by preserved intervertebral height, whereas in spinal osteoarthritis, reduced intervertebral disk height is common. These differences in the radiologic appearance and anatomic spinal distribution probably have to do with the different pathogenetic mechanisms described earlier. It is presumed that the primary target for the osteoarthritic process is the cartilage represented in the spine by the intervertebral disks and the cartilage of the facet joints.

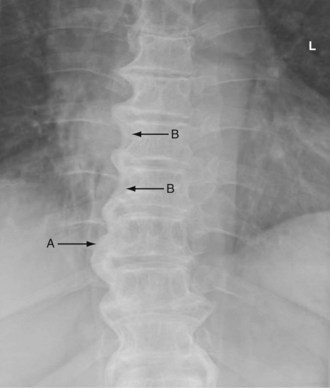

The wear-and-tear forces operating in the extremely mobile lower cervical and lumbar portions of the spine might explain the frequent involvement of these segments in osteoarthritis, whereas the thoracic spine is the least mobile of the spinal segments. The main targets of the disease in DISH are the spinal ligaments and entheses (Figure 102-1).5,49 These abnormalities are not limited to the thoracic spine and may involve the lumbar spine and the cervical spine (Figure 102-2). In the lumbar spine, the large bridging osteophytes are not uniformly one-sided.50 These sites of ossification and the subsequent production of large osteophytes may result in spinal stenosis51 and spinal stiffening, which increases the risk of fractures.52 These fractures may be unrecognized, unstable, and associated with treatment delays and permanent neurologic deficits. Severe complications may develop, especially when the cervical spine is affected including dysphagia, hoarseness, stridor, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, myelopathy, aspiration pneumonia, sleep apnea, atlantoaxial complications, thoracic outlet syndrome, esophageal obstruction, endoscopic and intubation difficulties, and fractures (Table 102-4).53 The high prevalence of coexisting intervertebral disk damage in young patients with DISH suggests an important role for DISH in the pathogenesis of spondylosis in this group of patients.54 At times, patients with DISH may assume the typical postural abnormalities of advanced ankylosing spondylitis such as accentuated kyphosis and reduced mobility of the spine. These two entities, although they may coexist, can usually be distinguished by the different age of onset, clinical presentation, radiographic appearance of the spine and sacroiliac joints, and HLA-B27 associations.55,56

Table 102-4 Clinical Manifestations of Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis in the Cervical Spine

| Spontaneous |

| Induced |

From Mader R: Clinical manifestations of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis of the cervical spine, Semin Arthritis Rheum 32:130–135, 2002.

Clinical manifestations similar or identical to those of osteoarthritis are prominent features of DISH in the peripheral joints. The peripheral joints affected by DISH have features that distinguish them from primary osteoarthritis, however. One is the more frequent involvement of joints that are not usually affected in osteoarthritis such as the metacarpophalangeal joints, elbows, and shoulders (Figure 102-3).57–60 Other features are a more severe hypertrophic disease that may result in a reduced range of motion in the affected joints and calcified and/or ossified prominent enthesopathies.59,61,62

As described previously, the primary event in DISH is thickening, calcification, or ossification of ligaments and entheses. In particular, enthesopathy affecting the peripheral joints has been described.63 The radiographic appearance of peripatellar, cruciate ligament insertion, and pericapsular osseous enthesopathies are some examples of the contribution of DISH to stiffening of the soft tissues surrounding a joint (Figure 102-4).64 Entheseal ossification at various sites other than joints such as the heel, ribs, and pelvis is a common finding in DISH. These enthesopathies may become symptomatic exhibiting pain and swelling in the affected region. A high probability for the presence of spinal DISH was noted for ossification of the iliolumbar and sacrotuberous ligaments and with bony overgrowth of the inferior acetabular rim.63,65 The tendency for new bone formation puts the patient at risk for the development of heterotopic ossification after joint surgery.

Figure 102-4 A and B, Ossified enthesopathies in the peripatellar, olecranon, and humeral epicondyles (arrows).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree