17

Musculoskeletal Disorders

Larry Collins and Helen E. Bateman

At the completion of this chapter the reader should be able to do the following:

1. Describe the anatomy of synovial joints

2. Recognize and identify common inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions in the child and adult athlete

3. Understand the underlying pathology of common rheumatologic disorders

4. Differentiate between the various inflammatory and noninflammatory rheumatologic disorders

5. Outline treatment plans and goals for inflammatory rheumatologic disorders

Overview of Anatomy and Physiology

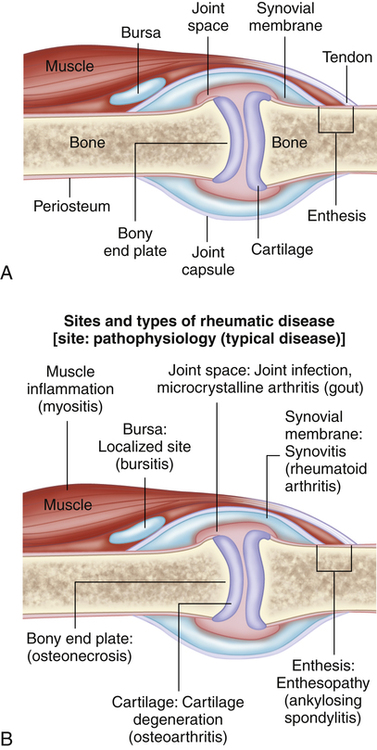

Synovial joints are the most common type of articulation within the human body. They are freely moveable joints characterized by the presence of a closed space or cavity between the articulating surfaces of the bones (Figure 17-1).

The articular capsule is a thick, double-layered membrane enclosing the joint cavity. The outer layer is a tough membrane of dense collagen fibers firmly attached to the surface of the bones near the metaphyseal–epiphyseal junction. It is continuous with the periosteum of the bone. The deeper layer of the capsule is the synovial membrane, which produces the synovial fluid that lubricates the joint.1–4

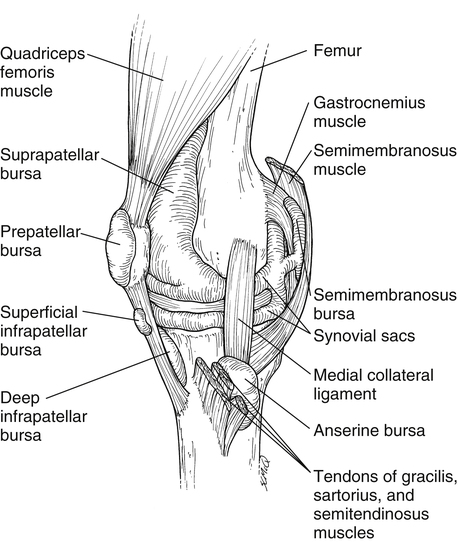

Synovial bursae are partially collapsed, balloon-like structures that are lined with a synovial membrane on the inside and have an external fibrous membrane. They are filled with synovial fluid and are found in the vicinity of joints where movement between two adjacent tissues might otherwise result in excessive friction. The bursae are located between bone, tendon, muscle, or skin, and they shield these structures from undue friction (Figure 17-2).

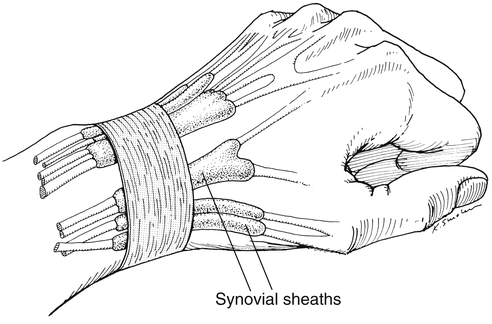

Tendon sheaths are similar to bursae, except they form around the length of a tendon, performing the same function as the bursa4 (Figure 17-3).

Assessment of the Musculoskeletal System

Range of motion and strength assessment is performed to determine loss of function and restriction of movement. When a neurological condition is suspected, a neurological examination is performed (see Chapters 2 and 11). When appropriate, special tests to determine the integrity of the ligamentous structures of the joint are performed.

Pathological Conditions

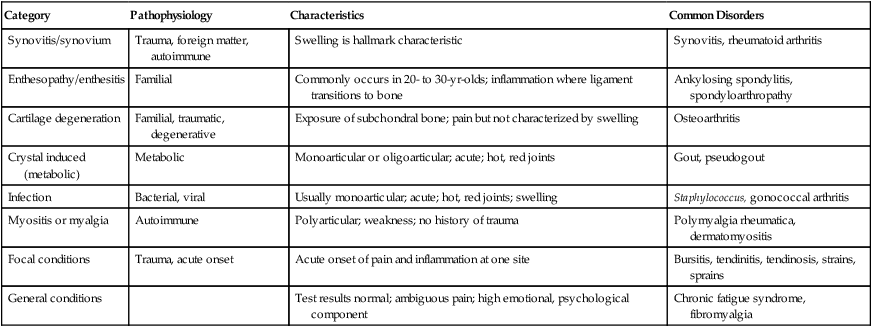

Musculoskeletal pathology may be divided into eight categories that are grouped according to the type of pathology or the action on the musculoskeletal system. Table 17-1 lists the general classifications and examples of disorders that fit into each category.

TABLE 17-1

Pathophysiology of Orthopedic Diseases

| Category | Pathophysiology | Characteristics | Common Disorders |

| Synovitis/synovium | Trauma, foreign matter, autoimmune | Swelling is hallmark characteristic | Synovitis, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Enthesopathy/enthesitis | Familial | Commonly occurs in 20- to 30-yr-olds; inflammation where ligament transitions to bone | Ankylosing spondylitis, spondyloarthropathy |

| Cartilage degeneration | Familial, traumatic, degenerative | Exposure of subchondral bone; pain but not characterized by swelling | Osteoarthritis |

| Crystal induced (metabolic) | Metabolic | Monoarticular or oligoarticular; acute; hot, red joints | Gout, pseudogout |

| Infection | Bacterial, viral | Usually monoarticular; acute; hot, red joints; swelling | Staphylococcus, gonococcal arthritis |

| Myositis or myalgia | Autoimmune | Polyarticular; weakness; no history of trauma | Polymyalgia rheumatica, dermatomyositis |

| Focal conditions | Trauma, acute onset | Acute onset of pain and inflammation at one site | Bursitis, tendinitis, tendinosis, strains, sprains |

| General conditions | Test results normal; ambiguous pain; high emotional, psychological component | Chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia |

Apophysitis

Apophysitis refers to inflammation of the apophysis and is sometimes referred to as osteochondrosis. It may be accompanied by widening or separation of the apophysis.5 It is typically caused by repetitive stress or traction on the apophysis. Normal physiological stresses on bone stimulate tissue breakdown and repair that are kept in balance. However, when activities increase, or rest is not adequate, the breakdown processes may overwhelm the repair process and lead to an inflammatory response with an eventual onset of symptoms. This increased stress may lead to delays or breakdowns in ossification with fragmentation of the apophysis and widening of the epiphyseal cartilage. Such fragmentation and widening can sometimes be seen on a plain radiograph (Figure 17-4). Apophysitis is often identified in relation to a specific body part or location. The following conditions are all considered apophysitis but are discussed according to their more common names.

Little League Shoulder

Also called proximal humeral epiphysiolysis, Little League shoulder was first described by Dotter in 1953.6 It is a stress fracture of the proximal humeral epiphyseal plate, which usually affects overhead throwers between the ages of 12 and 15 years, although it is now being seen in younger athletes. The exact etiology of this condition is not known, but repetitive overload on the epiphyseal plate is thought to be the common underlying cause.7

Signs and Symptoms

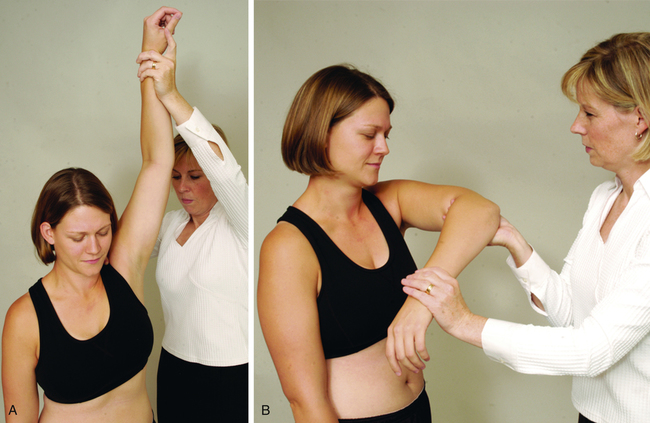

Physical examination is usually consistent with that seen in impingement syndrome in the older population, including pain with full elevation and at extremes of internal and external rotation of the shoulder. Generalized weakness and limited active range of motion, especially in abduction and internal–external rotation, may also be present.8,9 The positive Neer’s impingement sign (Figure 17-5, A) and the alternative Hawkins’ impingement test (Figure 17-5, B) generally reproduce pain, although probably from rotational forces on the proximal humerus as opposed to impingement of the rotator cuff. Pain is usually localized to the proximal lateral humerus.

Referral and Diagnostic Tests

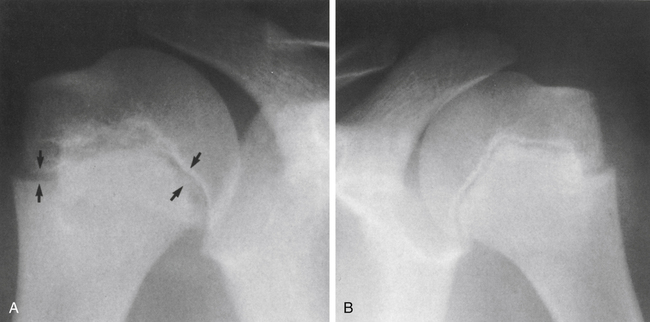

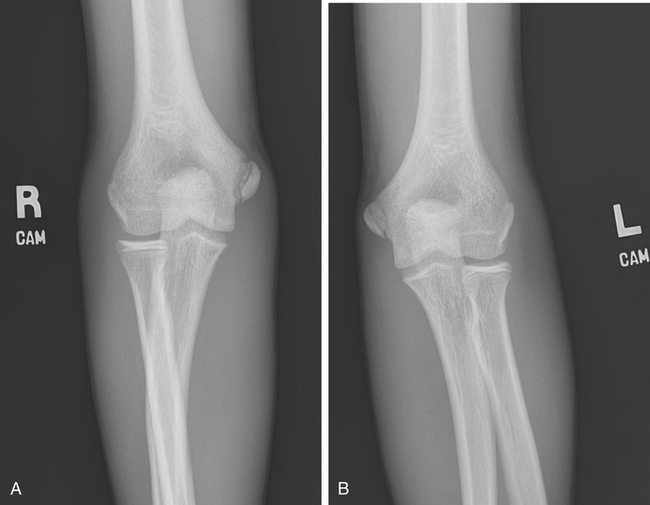

Comparison radiographs often show widening of the proximal humeral epiphyseal plate and sometimes show fragmentation (Figure 17-6). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually not necessary but will rule out rotator cuff pathology and may demonstrate edema at the epiphysis.

Treatment

Rest is the hallmark treatment for Little League shoulder. Typically the athlete must refrain from throwing for up to 3 months. Usually absolute rest is recommended for 2 to 6 weeks, followed by a conditioning program focusing on range of motion, rotator cuff strengthening, and scapular stabilization. As strength increases and symptoms decrease, a gradual return to throwing is begun according to a specific timetable based on strength and absence of symptoms. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be used to help decrease symptoms in the early stages of recovery.7

Prevention

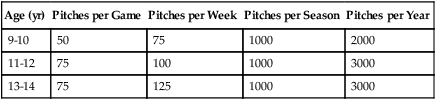

Because the symptoms of Little League shoulder are often brought about by an increase in throwing intensity or duration, it is imperative that pitch counts be monitored and regulated in youth baseball (Table 17-2). Gradual introduction of new pitches and increased number of pitches is paramount in the prevention of apophysitis of both the shoulder and the elbow.

TABLE 17-2

Recommended Limits for Youth Pitchers’ Pitch Counts

| Age (yr) | Pitches per Game | Pitches per Week | Pitches per Season | Pitches per Year |

| 9-10 | 50 | 75 | 1000 | 2000 |

| 11-12 | 75 | 100 | 1000 | 3000 |

| 13-14 | 75 | 125 | 1000 | 3000 |

Position Statement Available at http://www.asmi.org/asmiweb/usabaseball.htm. Accessed September 13, 2010. Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, et al: Effect of pitch type, pitch count, and pitching mechanics on risk of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers, Am J Sports Med 30:463–468, 2002; Youth Baseball Pitching Injuries. Available at http://web.usabaseball.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20090813&content_id=6409508&vkey=news_usab&gid= Accessed September 30, 2010.

Data from Andrews JR, Fleisig GS: USA Baseball Medical & Safety Advisory Committee Guidelines: May 2006.

Little League Elbow

Medial humeral epicondyle apophysitis, or Little League elbow, is often caused by repeated tensile stresses on the medial epicondyle.12 The apophysis of the medial epicondyle is typically the weak link in adolescents when compared with the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) or the flexor pronator mass. The specific etiology of medial humeral epicondyle apophysitis is still unclear; however, the traction forces of the UCL on the apophysis are the prime suspect. The highest levels of stress are created during the late cocking and early acceleration phases of throwing and may be significantly higher in the side-arm thrower.13,14

Differential Diagnosis

Other conditions involving the elbow that must be ruled out include osteochondrosis of the humeral capitellum or Panner’s disease, olecranon stress fracture, and ulnar nerve entrapment. In addition, ulnar collateral ligament sprain, flexor pronator strain, osteochondritis dissecans, synovitis, and infection must be ruled out.15

Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Osgood-Schlatter disease is one of the most common causes of anterior knee pain in the adolescent patient. Other common terms for this condition include epiphyseal aseptic necrosis of the tibial tubercle, osteochondritis of the tibial tuberosity, or patellar tendinitis. This condition was first described by American orthopedist Robert B. Osgood and Swiss physician Carl B. Schlatter.3 It typically affects adolescents 10 to 15 years of age, with the onset of symptoms usually associated with active periods of growth and/or rapid changes in activity levels.16–23 Explosive and eccentric activities are particularly aggravating to Osgood-Schlatter disease. It is often bilateral and may occur at an earlier age in girls than in boys. Osgood-Schlatter disease may occur once and resolve with appropriate measures or may present as recurring episodes associated with growth spurts throughout adolesence.3,15 Once the condition is resolved, the patient may have a more prominent tibial tubercle.

Treatment

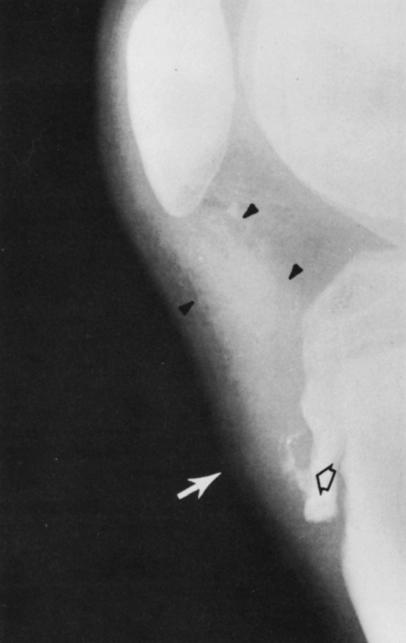

Surgery is rarely indicated in acute cases unless complete avulsion of the apophysis has occurred (Figure 17-9). In some cases, individuals may have anterior pain localized to the tubercle that does not resolve and may be a result of bony ossicles that have not completely fused (Figure 17-10). Surgery is sometimes indicated in these individuals if conservative treatment is not successful in decreasing their symptoms.

Sever’s Disease

Also known as calcaneal apophysitis, Sever’s disease occurs as a result of inflammation of the growth plate at the insertion of the Achilles tendon on the posterior calcaneus. Sever’s disease is usually a result of repetitive activities causing inappropriate stress on the growth center (similar to other apophysitis conditions) and typically occurs in children ages 8 to 14 years. On occasion it worsens as a result of specific trauma.3,24

Signs and Symptoms

Examination reveals pain and swelling directly over the insertion of the Achilles tendon on the calcaneus. The pain is generally aggravated by passive ankle dorsiflexion or resisted plantar flexion. Performing a single-leg heel raise is usually difficult and reproduces pain. Achilles tendon tightness is typically pronounced.24

Treatment

Rest remains the key to treatment. Icing and NSAIDs are helpful in decreasing inflammation. Gel heel inserts may help with the daily symptoms by decreasing the tension of the Achilles tendon on the calcaneus. On occasion a walking boot may be used to help with severe symptoms and still allow for mobilization and stretching. For displaced avulsions or severe symptoms, casting or splinting may be indicated. Range of motion and stretching exercises should be initiated early on with avoidance of explosive and eccentric activities.5,24

Scheuermann’s Disease

Scheuermann’s disease, also known as juvenile kyphosis, is a deformity affecting the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine of adolescents. Patients typically present with poor posture or deformity with or without back pain and stiffness. Scheuermann’s disease is thought to be a result of osteochondrosis of the anterior vertebral growth plate of the vertebral bodies and is most common in young males. This causes a narrowing of the anterior portion of the vertebral body, causing wedge-shaped vertebrae. It is seen most commonly in the lower thoracic spine from T7 through T9 and usually involves several vertebral bodies but may involve the entire thoracic and lumbar spine.3,25,26

Signs and Symptoms

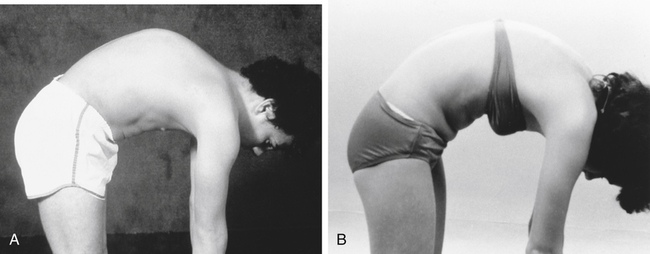

Physical examination usually reveals a kyphotic (humpback) deformity of 20 to 25 degrees that does not change when the patient bends forward in a flexed position (Figure 17-12). The kyphosis is commonly accompanied by scoliosis and a decrease in flexibility because of the structural nature of the deformity. Patients will usually have tenderness to palpation around the kyphosis. As with lower spine conditions, hamstring tightness is common. Although neurological complications are rare, a thorough neurological examination is essential (see Chapter 11).

Treatment

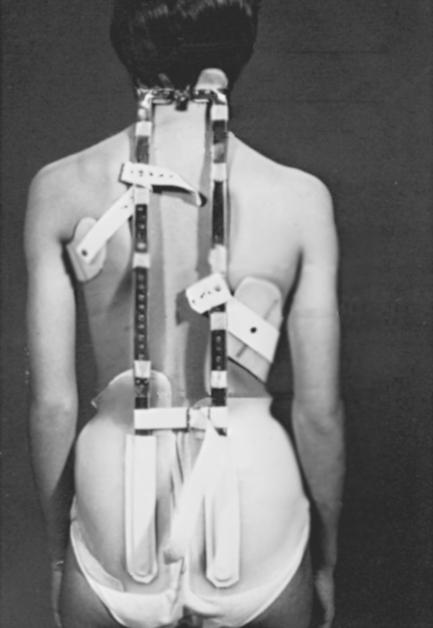

Core-strengthening and trunk stabilization exercises remain controversial in individuals with Scheuermann’s disease. Some believe that because this condition is usually self-limiting, no treatment is necessary.25,26 Others recommend strengthening to prevent associated back pain and stiffness.25,26 In more extreme cases, casting or bracing is appropriate (Figure 17-14). Orthotic management typically requires 12 to 24 months of treatment to show significant improvement and is done to prevent worsening of the condition as opposed to actually correcting the deformity.

NSAIDs are helpful for exacerbations, and activity restrictions to prevent hyperextension of the spine may be indicated. Surgery is rarely indicated and typically is for intractable pain or unacceptable cosmetic deformity.25,26

Avascular Necrosis

Avascular necrosis (AVN) is a condition resulting from the temporary or permanent loss of blood supply to a bone. With the blood supply gone, the cells within the bone die, eventually causing the bone to collapse. This may lead to collapse of the overlying articular surface of the bone and subsequently to arthritis (Figure 17-15). AVN is also referred to as osteonecrosis, subchondral bone avascularity, ischemic necrosis, or aseptic necrosis.

Avascular necrosis may affect one bone or more than one bone at the same time or over a period of time.3 The etiology of AVN is most commonly traumatic. Several risk factors are known and listed in Box 17-1. AVN may affect any bone, but is most commonly seen in the carpal scaphoid because of its recurrent blood supply. In bones with recurrent blood supply, the arterial supply passes the bone and its nourishment is supplied in a distal-to-proximal fashion. The scaphoid is an excellent example of this because a proximal fracture eliminates the possibility of blood supply to the injured area.

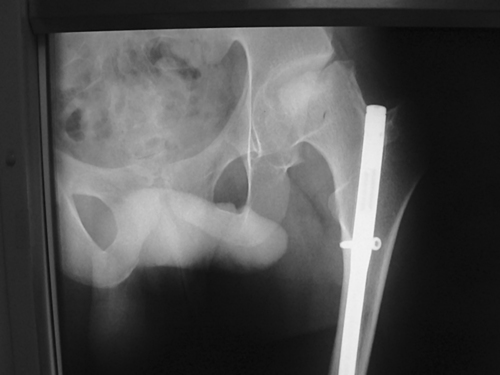

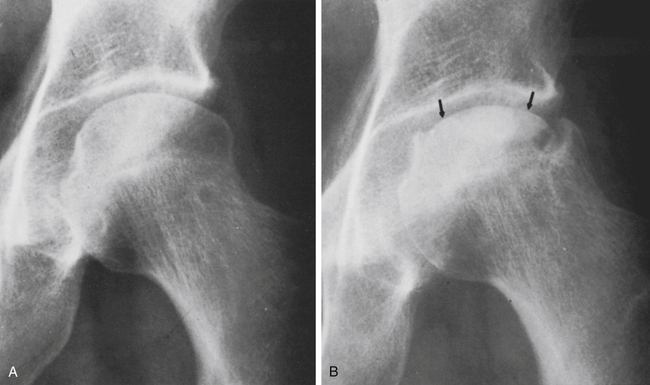

Up to 20% of individuals who sustain a femoral head or neck fracture develop AVN. In adults, presentation is typically seen in the fourth and fifth decades. High-dose corticosteroid use is associated with up to 35% of all cases of AVN, and alcohol abuse is also correlated with an increased risk of developing AVN.2–4 In children, AVN of the femoral head is termed Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease or coxa plana (Figure 17-16). Children with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease are usually between 4 and 14 years old, and present with increasing hip pain and often no history of injury or trauma.

Referral and Diagnostic Tests

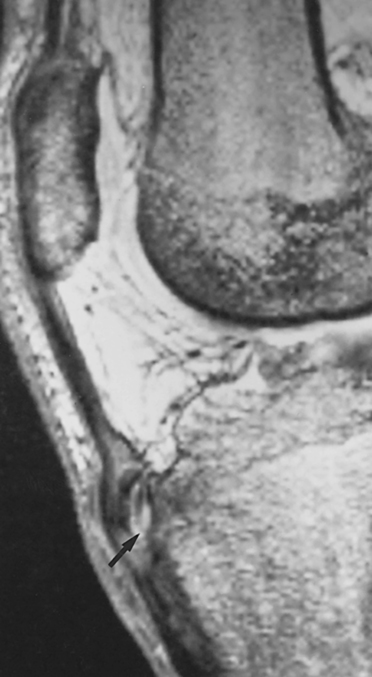

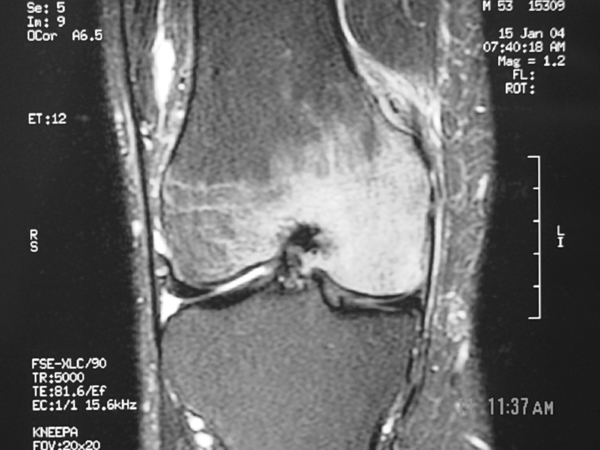

Radiographs are often normal when patients initially present but may show signs of early bone loss in aggressive cases (Figure 17-17). An MRI study is usually ordered for patients with suspected AVN because it is much more sensitive in detecting the disease in its early stages (Figure 17-18). The MRI is able to detect changes in the bone marrow and provides the physician with a better indication of the extent of the affected area. MRI has replaced the bone scan and computed tomography (CT) scan as the diagnostic study of choice for evaluating AVN.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree