Fig. 21.1

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS). A 27-year-old lady with hypermobility-type EDS lying on the examination table with her most comfortable posture. She has extremely loose joints with both her shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles as well as upper extremities (right). Right metacarpophalangeal joint hyperextension in the same patient (left)

An accurate physical examination is critical for diagnosis and adequate treatment of patients with MDI and loose shoulder. Patients should take their clothes off so that the scapula can be fully observed. First, the posture and position of the scapula should be examined. Typically, patients with loose shoulder or MDI demonstrate rounded back with bilaterally protracted scapulae. Next, shoulder motion is checked in both active and passive manner. We should pay attention to the scapular kinematics during the active motion. Passive range of motion is usually normal; however, many MDI or loose shoulder patients describe pain or apprehension during testing.

There are a variety of tests for evaluation of shoulder instability. However, the most important maneuver in the MDI examination is the sulcus test [2]. Inferior traction is placed on the limb with the arm at the side in neutral rotation. The test is positive when a dimple appears distal to the lateral acromion (Fig. 21.2). The test can be also performed with the arm in adduction, abduction, and both internal and external rotation. High degree of glenohumeral laxity is suspected when the displacement of the humeral head is more than 2 cm from the acromion; however, it is not necessarily abnormal unless the patient is symptomatic.

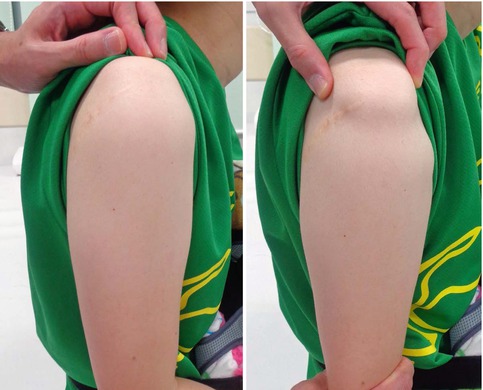

Fig. 21.2

Sulcus test in an MDI patient. Left: neutral (no traction), Right: inferior traction is placed and the dimple is clear

The load and shift test is also frequently used to examine shoulder instability. The test is performed in the sitting position and with the arm at the side in neutral rotation. The humeral head is centered in the glenoid by applying an axial load. The proximal humerus is then translated to determine instability (Fig. 21.3). The test is graded in terms of the degree of translation: grade 0, no translation; grade 1, translation to the glenoid rim; grade 2, dislocation with spontaneous reduction; and grade 3, dislocation without spontaneous reduction.

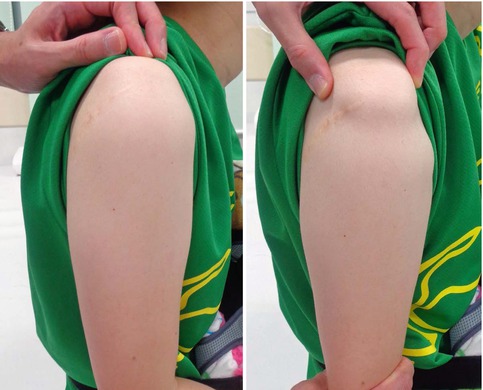

Fig. 21.3

Load and shift test in an MDI patient. Right: anterior translational force is applied. Left: posterior translational force is applied

Other tests for anterior instability include the anterior apprehension test, the relocation test, and the fulcrum test. Tests for posterior instability include the posterior apprehension test and the jerk test. The jerk test is sensitive for posterior instability and is performed in the sitting position. While stabilizing the patient’s scapula with one hand and holding the affected arm at 90° abduction and internal rotation, the examiner grasps the elbow and axially loads the humerus in a proximal direction. The arm is moved horizontally across the body. The test is positive when the humeral head slides off the back of the glenoid with a sudden clunk [10, 11].

21.4 Essential Radiology

Diagnosis of MDI is primarily clinical; however, imaging is also helpful in some circumstances. Occasionally, standard radiographs reveal abnormal glenoid version, dysplasia, or hypoplasia. In my institute, we always take bilateral shoulder radiographs with the arms elevated in addition to standard anteroposterior views for young athletes. The radiographs in the elevated position sometimes demonstrate slipping of the humeral head in patients with loose shoulder (Fig. 21.4).

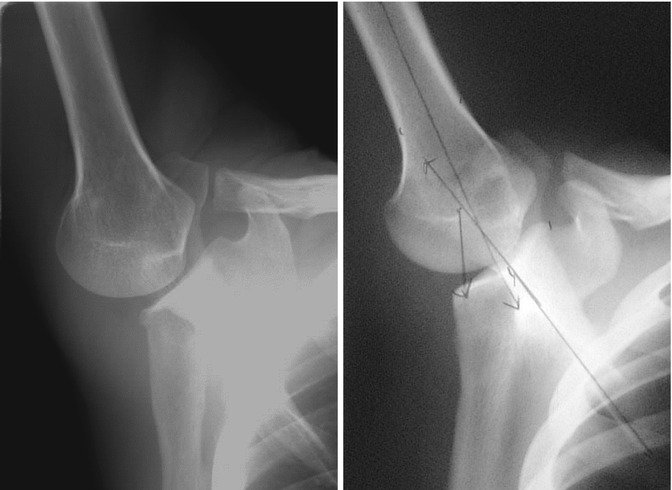

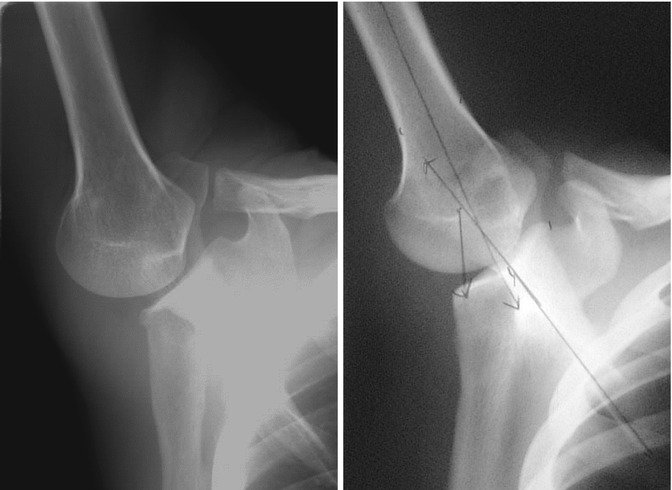

Fig. 21.4

Humeral head slipping in a throwing athlete with loose shoulder. Right: normal. Left: loose shoulder

CT scans are optional; however, they can be helpful for precise evaluation of the glenoid shape and version if abnormalities of the glenoid are suspected with standard radiographs. Reformatted and three-dimensional CT can be useful to evaluate the abnormal glenoid morphology.

MRI is frequently used for detecting pathologies in soft tissue in patients with shoulder instability. MR arthrography is preferred to evaluate unstable shoulders because the capsule can be distended, thereby improving definition of the labrum, rotator interval, and glenohumeral ligaments. Frequent finding is increased volume of the glenohumeral joint [3], and labral abnormalities including labral tears are sometimes seen in patients with MDI or loose shoulder (Fig. 21.5). However, these findings are nonspecific and may not reflect actual instability.

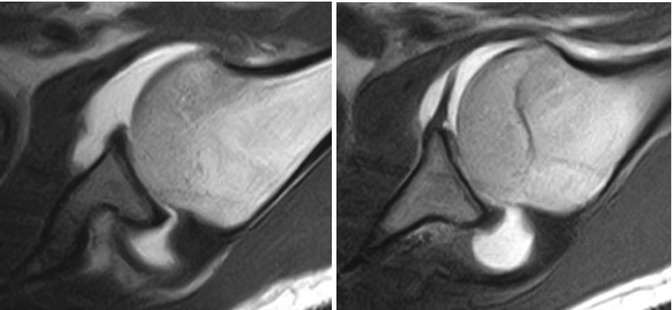

Fig. 21.5

MR arthrography (ABER view)

21.5 Disease-Specific Clinical and Arthroscopic Pathologies

Patients with MDI or loose shoulder complain pain with the arm in a certain position and/or involuntary dislocation/subluxation and sensation of looseness of their affected shoulder. As described above, majority of patients are accompanied by scapular dysfunction, such as protracted and anteriorly tilted scapula with downward rotation. In addition, they may also loose normal mobility/flexibility in their thoracic spine and rib cage associated with round back. Therefore, the first choice of treatment is to correct these functional problems, and this responds relatively well in the majority of patients [12].

However, even after optimal physical treatment for a certain period, maybe at least 3–6 months, if patients remain symptomatic, surgery is then indicated. As described below, the gold standard of surgical treatment is arthroscopic capsulorrhaphy. When surgeons put the scope into the glenohumeral joint, they often recognize redundant capsule characterized with wide intra-articular space and poor and thin capsular tissue (Fig. 21.6). Sometimes, the labrum and biceps tendon as well as the middle and inferior glenohumeral ligament are also hypoplastic. Although subtle labral injuries are sometimes associated in patients with MDI or loose shoulder, distinct traumatic lesion is not normally observed even after patients become dramatically symptomatic after a certain traumatic event (Fig. 21.7).

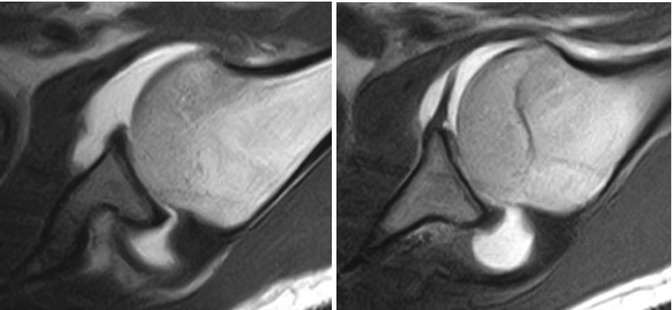

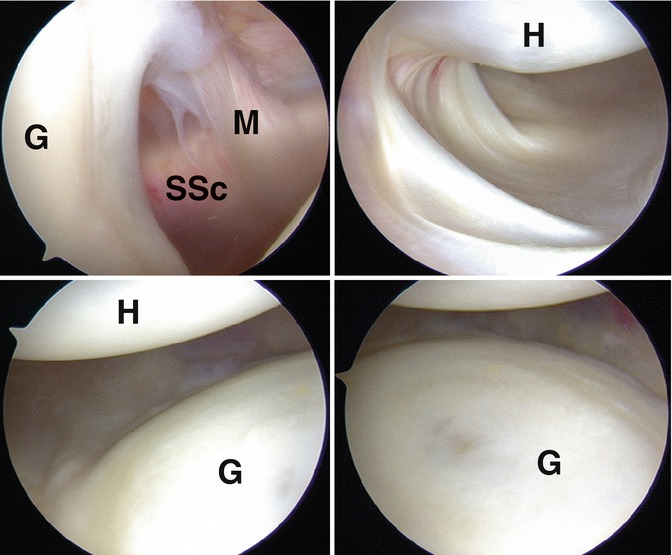

Fig. 21.6

Arthroscopic findings of an MDI patient. The right shoulder is viewed from the posterior portal. Although no anatomical disruption is identified, wide and redundant capsule and thin MGHL are observed. G glenoid, H humeral head, SSc subscapularis, M MGHL

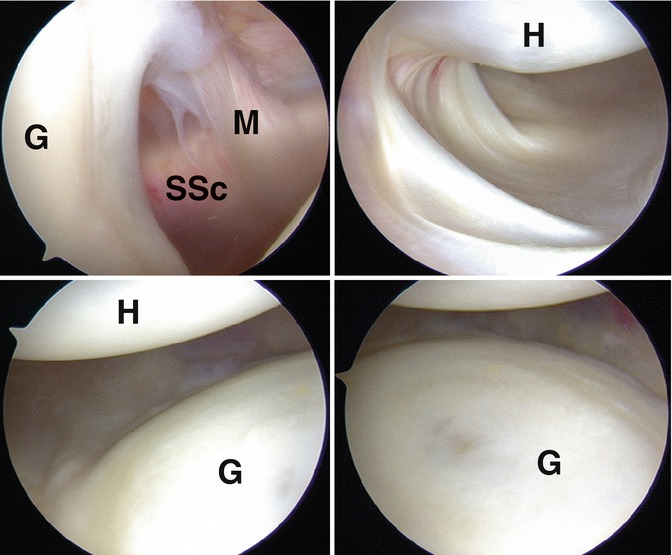

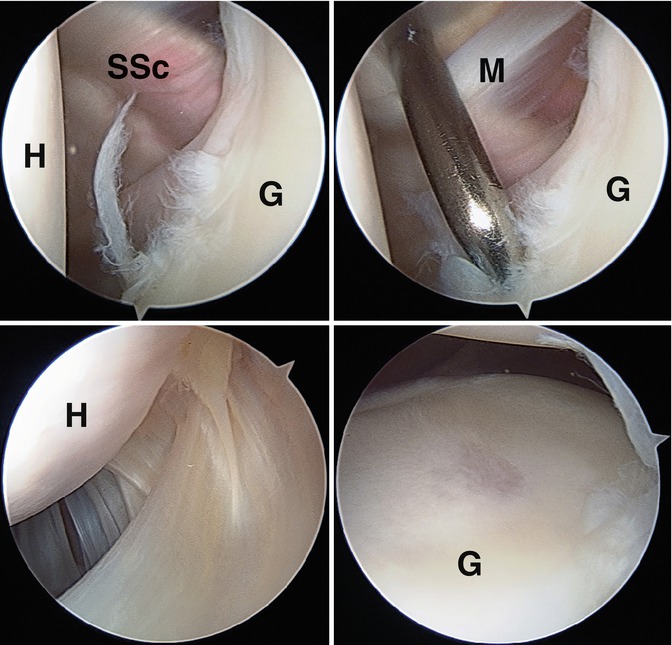

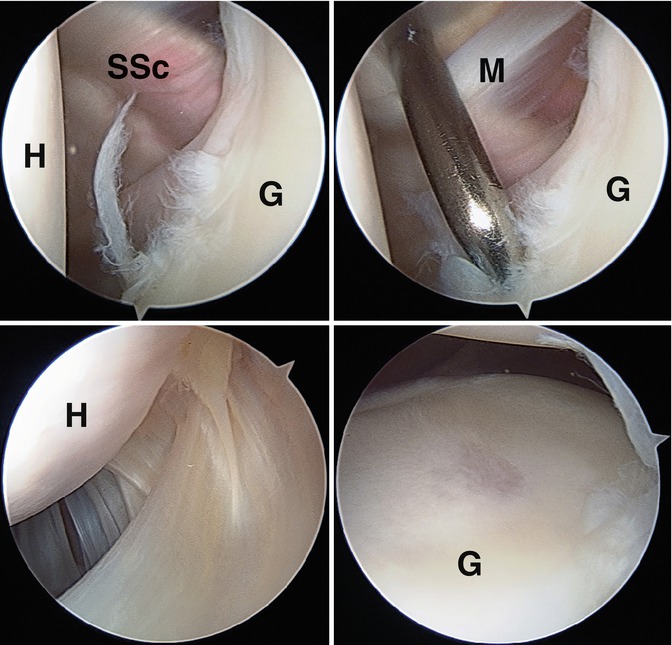

Fig. 21.7

Arthroscopic findings of traumatic shoulder instability associated with loose shoulder. The right shoulder is viewed from the posterior portal (above left and right, below left) and the anterior portal (below right). Slight disruption of the anterior labrum is observed (above left and right) along with a thin, wide capsule (below left and right). After the last traumatic event, this patient became dramatically symptomatic as she could not hold her arm without a sling until surgery despite this subtle lesion. G glenoid, H humeral head, SSc subscapularis, M MGHL

21.6 Treatment Options

The standard of care for initial treatment of MDI is rehabilitation. Nonoperative management is successful in approximately 80 % of patients with MDI [12]. Rehabilitation aims for rotator cuff strengthening to maximize the concavity-compression mechanism and scapular stabilization to stabilize the glenoid platform [6]. Improving the dynamic positioning of the glenoid and instituting a proprioceptive exercise program can improve the efficacy of dynamic glenohumeral stabilizers. A minimum of 6-month trial of therapy should be devoted to improving stability; however, some authors suggest that longer periods may be required [13].

Burkhead and Rockwood reported good or excellent results of nonoperative treatment in 83 % of patients with atraumatic shoulder instability [12]. However, Misamore et al. [14] reported poor outcomes in a long-term follow-up study. In a cohort of young and athletic patients, 19 of 36 were rated as having poor results with the modified Rowe grading scale, and only 8 patients were free of all pain and instability at a mean of an 8-year follow-up [14]. This study indicates that athletic patients with MDI may have a less favorable response to rehabilitation. It may be important to establish better rehabilitation program to maximize long-term outcomes in athletic patients. However, we should not hesitate to apply surgical intervention for athletic patients who have a less favorable response to nonoperative treatment.

Surgical treatment should be considered in patients who continue to have debilitating symptoms despite of an appropriate rehabilitation. Surgical management should be individualized to address the anatomic cause of shoulder instability.

The open inferior capsular shift emerged as a successful treatment of MDI following its introduction by Neer and Foster in 1980 [2]. In this technique, the subscapularis is tenotomized, and the capsule is released from the humerus from anterior to posterior. A T-shape incision is made between the middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments, and the inferior leaflet is shifted superiorly while the superior leaflet is shifted inferiorly. This procedure reduces posterior capsular redundancy and eliminates the inferior capsular pouch. The subscapularis is then reattached superficially to the reconstructed capsule. Neer and Foster reported that instability was eliminated in 39 out of 40 shoulders [2]. Since then, multiple other studies have shown satisfactory outcomes. However, rates of return to sports remain less than optimal. Pollock et al. reported that only 25 out of 36 athletes (69 %) were able to return to previous levels of sporting activity following the open inferior capsular shift procedure [15]. The major cause of the low return rates may be the damage to the subscapularis. Thus, arthroscopic treatment has risen, which has an advantage in the preservation of the subscapularis and the ability of better visualization of the entire capsulolabral anatomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree