91 Immune Complex–Mediated Small Vessel Vasculitis

The inflammation within blood vessel walls that characterizes vasculitis frequently leads to cellular destruction, damage to the vascular structures, compromise of blood flow to organs, and organ dysfunction. It has been known for decades that immune complex (IC)–mediated mechanisms play critical roles in many forms of systemic vasculitis, particularly those that involve primarily small blood vessels. As described in Chapter 87, the use of horse serum and sulfonamides as therapeutic agents for infectious diseases in the early 1900s frequently led to small vessel vasculitis on the basis of serum sickness or hypersensitivity phenomena. Hypersensitivity angiitis, often confused with the pauci-immune form of vasculitis now termed microscopic polyangiitis (see Chapter 89),1 was one of five disorders included in the original classification of the vasculitides in 1952.2

This chapter focuses on forms of small vessel vasculitis that are mediated by IC deposition. These disorders include hypersensitivity vasculitis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), mixed cryoglobulinemia, hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis, and erythema elevatum diutinum. In addition, forms of vasculitis associated with connective tissue diseases, particularly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome, and rheumatoid vasculitis, are discussed briefly. Anti–glomerular basement membrane disease and the pauci-immune forms of vasculitis such as those associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, are discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 89). Throughout this chapter, the terms vasculitis and angiitis are used interchangeably when referring to inflammation involving small blood vessels (capillaries, venules, arterioles).

Because all forms of IC-mediated vasculitis share certain elements of pathogenesis, have many cutaneous findings in common, and have overlapping differential diagnoses, these aspects of the disorders are considered together. The epidemiology, cause, distinctive pathophysiologic mechanisms, unique clinical features, and approaches to treatment are discussed separately for each condition. Treatments are also summarized in Table 91-1.

Table 91-1 Potential Treatment Approaches for Different Forms of Immune Complex–Mediated Vasculitis

| Disease | Preferred Treatment Approach |

|---|---|

| Hypersensitivity vasculitis | |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | No treatment required in the majority of cases, particularly children (symptomatic therapy only) Moderate glucocorticoid doses (prednisone 20-40 mg/day) are of variable utility but may be used empirically in patients with disabling symptoms Pulse glucocorticoids (e.g., 1 g methylprednisolone/day) employed with anecdotal success for refractory purpura when moderate glucocorticoid doses have failed Refractory glomerulonephritis may require high-dose glucocorticoids, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide |

| Cryoglobulinemia | |

| Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis | |

| Erythema elevatum diutinum | |

| Connective tissue disease | |

| Rheumatoid vasculitis |

Pathogenesis

Arthus Reaction

The Arthus reaction, described after the injection of horse serum into rabbits, forms the basis of our understanding of IC-mediated diseases.3 The formation of ICs in the Arthus reaction initiates complement activation and an influx of inflammatory cells, followed by thrombus formation and hemorrhagic infarction in the areas of most intense inflammation. ICs, formed by the combination of antibody and antigen, are continuously created (and usually cleared swiftly and efficiently) by the reticuloendothelial system as a means of neutralizing foreign antigens. Under some circumstances, however, ICs escape clearance and become deposited within joints, blood vessels, and other tissues, inciting inflammation and causing disease. ICs deposited in the blood vessel walls lead to vasculitis. Similarly, those deposited within small blood vessels of the kidney—the glomeruli—cause glomerulonephritis.4

Cutaneous Manifestations

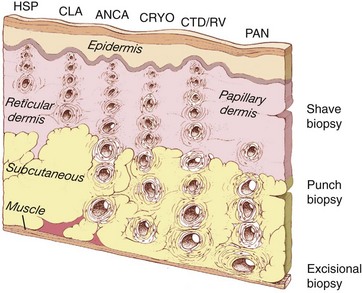

Small blood vessels generally include capillaries, postcapillary venules, and nonmuscular arterioles—vessels that are typically less than 50 µm in diameter. These are found principally within the superficial papillary dermis (Figure 91-1). Medium-sized blood vessels, those between 50 and 150 µm in diameter, contain muscular walls and are located principally in the deep reticular dermis, near the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Vessels larger than 150 µm in diameter are not commonly found in the skin.

Figure 91-1, which demonstrates the location and size of blood vessels involved in various types of cutaneous vasculitis, illustrates the types of blood vessels affected by several forms of IC-mediated disease. A blood vessel’s size correlates closely with its depth in the skin layers: The larger the vessel, the deeper its location. Although telltale signs of vasculitis may be evident on inspection of the skin’s surface, the epidermis is avascular. Therefore the pathologic findings in cutaneous vasculitides lie within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.

Palpable purpura, synonymous with small vessel vasculitis, is the most common cutaneous finding in IC-mediated vasculitis (Figure 91-2). Purpuric lesions result from the extravasation of erythrocytes through damaged blood vessel walls into tissue. Many other skin manifestations are possible in these conditions including vesicles, pustules, urticaria, superficial ulcerations, nonpalpable lesions (macules and patches), and splinter hemorrhages (Figure 91-3). These lesions frequently occur in combination, and careful examination usually reveals a purpuric component. Purpuric lesions do not blanch when pressure is applied to the skin. Following resolution, purpuric lesions may leave postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, particularly if repeated bouts occur (see Figure 91-3F).

Figure 91-2 Hypersensitivity vasculitis. Palpable purpura in a patient with hypersensitivity vasculitis.

In IC-mediated vasculitis, purpuric lesions are usually distributed in a symmetric fashion over dependent regions of the body, particularly the lower legs, because of the increased hydrostatic pressure in these areas. Purpuric lesions are not always palpable to the touch, and the existence of palpable purpura does not necessarily imply an IC-mediated pathophysiology; pauci-immune forms of vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) (formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis), microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome, for example, may present with identical skin findings (albeit distinctive histopathology; see Chapter 89).

Pathologic Features

Light Microscopy

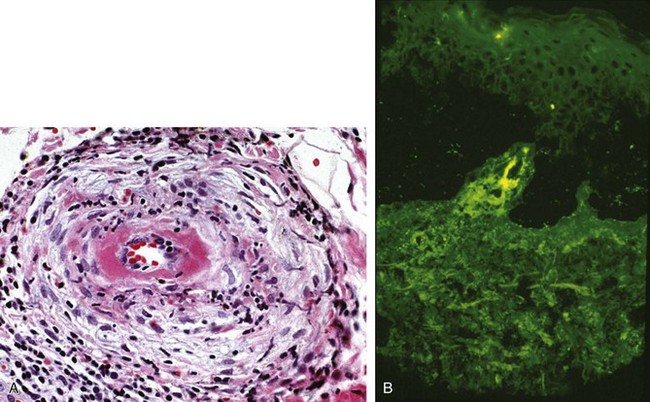

Figure 91-4A displays the light microscopy findings of cutaneous vasculitis. The optimal time for skin biopsy is 24 to 48 hours after the appearance of a lesion. Biopsies should be obtained from a nonulcerated site. For ulcerated lesions—usually more of an issue with medium vessel vasculitides—biopsies should be taken from the ulcer’s edge. The cellular infiltrates in cutaneous vasculitis are usually made up of a combination of neutrophils and lymphocytes, but most cases demonstrate a predominance of one cell type or the other. Lymphocyte-rich infiltrates may be seen in specimens taken from either new (<12 hours) or old (>48 hours) lesions, regardless of the underlying type of vasculitis. Even in connective tissue disorders such as Sjögren’s syndrome, the typical finding is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis rather than a lymphocytic vasculitis.5

The essential histologic feature in any form of cutaneous vasculitis is the disruption of blood vessel architecture by an inflammatory infiltrate within and around the vessel walls. Endothelial swelling and proliferation, leukocytoclasis (degranulation of neutrophils, leading to the production of nuclear “dust”; see Figure 91-4), and extravasation of erythrocytes may be evident in the biopsy but are not essential to the diagnosis.

Direct Immunofluorescence

Although the diagnosis of cutaneous vasculitis rests on routine histology, the features revealed by hematoxylin and eosin stains do not distinguish between pauci-immune and IC-mediated disorders. DIF studies complement the histologic information, provide the only way of diagnosing HSP with certainty, and yield important clues regarding the nature of the underlying disease. The performance of separate biopsies for histologic and DIF analyses is recommended if sufficient lesions exist. With DIF studies, frozen sections are incubated with fluorescein-labeled anti–human immunoglobulin (Ig) G, IgM, IgA, and C3. The staining patterns of these immunoreactants may provide insight into not only the diagnosis but also the pathophysiology of certain conditions. Figure 91-4B displays the typical DIF findings in a skin lesion from a patient with IC-mediated vasculitis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of IC-mediated small vessel vasculitis is shown in Table 91-2. There are three main groups of disorders in the differential diagnosis of IC-mediated small vessel vasculitis: other forms of IC-mediated disorders, forms of small vessel vasculitis that are not mediated through ICs, and vasculitis mimickers that involve small blood vessels. A diagnostic algorithm that includes the critical laboratory and radiographic tests is shown in Figure 91-5.

Table 91-2 Differential Diagnosis of Immune Complex–Mediated Vasculitis

| Immune Complex–Mediated Vasculitides |

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|