105 Heritable Diseases of Connective Tissue

Heritable disorders of connective tissues are a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by abnormalities in skeletal tissues including cartilage, bone, tendon, ligament, muscle, and skin. These disorders, originally defined by McKusick,1 have been classified on the basis of clinical findings and molecular criteria. They are subclassified into disorders that primarily affect cartilage and bone (the skeletal dysplasias) and disorders that have a more profound effect on connective tissue including Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), Marfan syndrome, and other disorders manifested by abnormal extracellular matrix molecules. The skeletal dysplasias are associated with abnormalities in the size and shape of the appendicular and axial skeleton and frequently result in disproportionate short stature. Until the early 1960s, most individuals with short stature were considered to have pituitary dwarfism, achondroplasia (short-limb dwarfism), or Morquio disease (short-trunked dwarfism). Presently, there are more than 450 well-characterized disorders that are classified primarily on the basis of clinical, radiographic, and molecular criteria.2 Disorders of connective tissue are genetic defects that result from mutations in genes that encode extracellular matrix proteins, transcription factors, tumor suppressors, signal transducers, enzymes, chaperones, intracellular binding proteins, ribonucleic acid (RNA) processing molecules, and genes of unknown function.

Skeletal Dysplasias

The skeletal dysplasias, or osteochondrodysplasias, are defined as disorders that are associated with a generalized abnormality in the skeleton. Although each skeletal dysplasia is relatively rare, collectively, the birth incidence of these disorders is almost 1 in 5000.3 These disorders range in severity from “precocious” arthropathy to perinatal lethality owing to pulmonary insufficiency. Individuals with these disorders can have significant orthopedic, neurologic, and psychological complications. Many of these individuals seek medical attention for orthopedic complaints owing to ongoing pain, arthritic complaints in large joints, and back pain primarily caused by ongoing abnormalities in bone and cartilage frequently leading to spinal stenosis.

Embryology

The patterning and architecture of the skeleton occurs during fetal development (see Chapter 4). During that period, the number, size, and shape of the future skeletal elements are determined, a process that is under complex genetic control.4 Uncondensed mesenchyme undergoes cellular condensations (cartilage anlagen) at the sites of future bones, and this occurs via two mechanisms.5 In the process of endochondral ossification, mesenchyme first differentiates into a cartilage model (anlagen), and then the center of the anlagen degrades, mineralizes, and is removed by osteoclast-like cells. This process spreads up and down the bones and allows for vascular invasion and influx of osteoprogenitor cells. The periosteum in the midshaft region of the bone produces osteoblasts, which synthesize the cortex; this is known as the primary ossification center.

At the ends of the cartilage anlagen, a similar process leading to the removal of cartilage occurs (secondary center of ossification), leaving a portion of cartilage model “trapped” between the expanding primary and secondary ossification centers. This area is referred to as a cartilage growth plate or epiphysis. Four chondrocyte cell types exist in the growth plate: reserve, resting, proliferative, and hypertrophic. These growth plate chondrocytes undergo a tightly regulated program of proliferation, hypertrophy, degradation, and replacement by bone (primary spongiosa). This is the major mechanism of skeletogenesis and is the mechanism by which bones increase in length, and the articular surfaces increase in diameter. In contrast, the flat bones of the cranial vault and part of the clavicles and pubis form by intramembranous ossification, whereby fibrous tissue, derived from mesenchymal cells, differentiates directly into osteoblasts, which directly lay down bone.5 These processes are under specific and direct genetic control, and abnormalities in the genes that encode these pathways frequently lead to skeletal dysplasias.6–9

Cartilage Structure

Collagen accounts for two-thirds of the adult weight of adult articular cartilage and provides significant strength and structure to the tissue (see Chapter 3). Collagens are a family of proteins that consist of single molecules (monomers) that combine into three polypeptide chains to form a triple helix structure. In the triple helix, every third amino acid is a glycine residue and the general chain structure is denoted as Gly-X-Y, where X and Y are commonly proline and hydroxyproline. The collagen helix can be composed of identical chains (homotrimeric), as in type II collagen, or can consist of different collagen chains (heterotrimeric), as seen in collagen type XI.10

Collagens are widely distributed throughout the body, and 33 collagen gene products are expressed in a tissue-specific manner, leading to 19 triple helical collagens. Collagens are classified further by the structures they form in the extracellular matrix. The most abundant collagens are the fibrillar types (I, II, III, V, and XI), and their extensive cross-linking provides mechanical strength that is necessary for high stress tissue such as cartilage, bone, and skin.11 Another collagen species is the fibril-associated collagens with interrupted triple helices, which include collagen types IX, XII, XIV, and XVI. These collagens interact with fibrillar collagens and other extracellular molecules including aggrecan, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, and other sulfated proteoglycans.11 Collagen types VIII and X are nonfibrillar, short-chain collagens, and type X collagen is the most abundant extracellular matrix molecule expressed by hypertrophic chondrocytes during endochondral ossification.12 The major collagens of articular cartilage are fibrillar collagen types II, IX, X, and XI. In developing cartilage, the core fibrillar network is a cross-linked copolymer of collagens II, IX, and XI.13 Mutations in genes that encode these collagens and proteins involved in their processing result in various skeletal dysplasias and highlight the importance of these molecules in skeletal development.

Classification and Nomenclature

As mentioned earlier, in the 1970s, there was recognition of the genetic and clinical heterogeneity of heritable disorders of connective tissue and a new awareness of the complexity of these disorders. As a result, there have been multiple attempts to classify these disorders in a manner that clinicians and scientists could use effectively to diagnose and determine their pathogenicity (International Nomenclature of Constitutional Diseases of Bone, 1970, 1977, 1983, 1992, 2001, 2005, 2010). The initial categories were purely descriptive and clinically based. With the more recent explosion in determining the genetic basis of these diseases, the classification has evolved into one that combines the older clinical one (including the eponyms and Greek terms) and blends these disorders into families that share a molecular basis or pathway. The most recent updated classification can be found at www.isds.ch. Some of the chondrodysplasia families are listed in Table 105-1.

Table 105-1 Classification of the Chondrodysplasias

| Dysplasia | Inheritance | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| Achondroplasia Group | ||

| Achondroplasia | AD | FGFR3 |

| Thanatophoric dysplasia, type I | AD | FGFR3 |

| Thanatophoric dysplasia, type II | AD | FGFR3 |

| Achondroplasia | AD | FGFR3 |

| Hypochondroplasia | AD | FGFR3 |

| SADDAN | AD | FGFR3 |

| CATSHL | AD | FGFR3 |

| Osteogleophonic dsyplasia | AD | FGFR1 |

| Severe Spondylodyplastic Dysplasias | ||

| Achondrogenesis IA | AR | GMAP210 |

| Opsismodysplasia | AR | Unknown |

| Schneckenbecken dysplasia | AR | SLC35D1 |

| Spondylometaphsyeal dysplasia, type Sedaghatian | AR | SBDS |

| TRPV4/Metatropic Dysplasia Group | ||

| Metatropic dysplasia | AD | TRPV4 |

| Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (Kozlowski type) | AD | TRPV4 |

| Parastrammetic dysplasia | AD | TRPV4 |

| Brachyolmia (AD) | AD | TRPV4 |

| Short Rib Dysplasia (Polydactyly) Group | ||

| Short-rib polydactyly type I/III | AR | DYNC2CH1 |

| IFT80 | ||

| WDR35 | ||

| Short-rib polydactyly type II/IV | AR | NEK1 |

| Asphyxiating thoracic dysplasia | AR | DYNC2CH1 |

| IFT80 | ||

| Chondroectodermal dysplasia | AR | EVC1, EVC2 |

| Thoracolaryngopelvic dysplasia | AD | Unknown |

| Filamin-Related Disorders | ||

| Atelosteogenesis I | AD | FLNB |

| Atelosteogenesis III | AD | FLNB |

| Larsen syndrome | AD | FLNB |

| Otopalato-digital syndrome type II | XLR | FLNA |

| Osteodysplasty, Melnick-Needles | XLD | FLNA |

| Diastrophic Dysplasia Group | ||

| Achondrogenesis IB | AR | DTDST |

| Achondrogenesis II | AR | DTDST |

| Diastrophic dysplasia | AR | DTDST |

| Recessive multiple epiphyseal dysplasia | AR | DTDST |

| Dyssegmental Dysplasia Group | ||

| Dyssegmental dsyplasia | AR | HSPG2 |

| Silverman-Handmaker type | AR | HSPG2 |

| Dyssegmental dsyplasia | AR | HSPG2 |

| Rolland-Desbuquois | ||

| Schwartz-Jampel syndrome | AR | HSPG2 |

| Type II Collagenopathies | ||

| Achondrogenesis II | AD | COL2A1 |

| Kniest dysplasia | AD | COL2A1 |

| Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita | AD | COL2A1 |

| Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia | AD | COL2A1 |

| Strudwick type | ||

| Spondyloperipheral dysplasia | AD | COL2A1 |

| Arthro-opthamalopathy (Stickler syndrome) | AD | COL2A1 |

| Type XI Collagenopathies | ||

| Stickler dysplasia | AD | COL11A1 |

| OSMED | AR | COL11A2 |

| Weissenbacher-Zweymuller syndrome | AD | COL11A2 |

| Fibrochondrogenesis | AR | COL11A1 |

| COL11A2 | ||

| Other Spondyloepi-(meta)-physeal [SE(M)D] Dysplasia | ||

| Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia, Pakistani type | AR | ATPSK2 |

| Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia tarda | XLR | SEDL |

| Progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia | AR | WISP3 |

| Dyggve-Melchior-Clausen dysplasia | AR | FLJ90130 |

| Wolcott-Rallison dysplasia | AR | EIF2AK3 |

| Acrocapitofemoral dysplasia | AR | IHH |

| Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia | AR | SMARCAL1 |

| Sponastrime | AR | Unknown |

| Spondlyometaphyseal dysplasia, type corner fracture | AD | Unknown |

| Multiple Epiphyseal Dysplasia and Pseudoachondroplasia | ||

| Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia | AD | COL9A1 |

| COL9A2 | COL9A3 | |

| MATN | COMP | |

| Pseudoachondroplasia | AD | COMP |

| Chondrodysplasia Punctata | ||

| Chondrodysplasia punctata, rhizomelic type | AR | PEX7 |

| DHAPAT | ||

| AGPS | ||

| Chondrodysplasia punctata, Conradi-Hunermann type | XLD | EBP |

| Hydrops-ectopic calcifications- moth-eaten bones | AR | LBR |

| Chondrodysplasia punctata, brachytelephalangic type | XLR | ARSE |

| Chondrodysplasia punctata, tibial-metacarpal type | AD | Unknown |

| Metaphyseal Dysplasias | ||

| Metaphsyeal chondrodysplasia, type Jansen | AD | PTHrP |

| Eiken dysplasia | AR | PTHrP |

| Bloomstrand dysplasia | AR | PTHrP |

| Metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, type Schmidt | AD | COL10A1 |

| Metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, McKusick type | AR | RMRP |

| Metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, with pancreatic insufficiency, and cyclin neutropenia | AR | SBDS |

| Adenosine deaminase deficiency | AR | ADA |

| Brachyolmia Spondylodysplasias | ||

| Brachyolmia (Hobek type) | AR | Unknown |

| (Toledo type) | ||

| Brachyolmia (Maroteaux type) | AR | Unknown |

| Rhizo- and Mesomelic Dysplasias | ||

| Omodysplasia | AR | Glypican 6 |

| Dyschondrosteosis | XLD | SHOX |

| Mesomelic dysplasia, type Lange | XLR | SHOX |

| Mesomelic dysplasia, type Robinow | AD | |

| AR | ROR2 | |

| Mesomelic dysplasia, Kantapura type | AD | Duplication in the Hox cluster |

| Acromelic and Acromesomelic Dysplasias | ||

| Acromicric dysplasia | AD | Fibrillin 1 |

| Geleophysic dysplasia | AD | Fibrillin 1 |

| AR | ADAMTSL2 | |

| Trichorhinophalangeal dysplasia, type I | AD | TRPS1 |

| Trichorhinophalangeal dysplasia, type II | AD | TRPS2 |

| Acrodysostosis | AD | PRKAR1A |

| Grebe dysplasia | AR | CDMP1 |

| Acromesomelic dysplasia, Hunter-Thompson | AR | CDMP1 |

| Acromesomelic dysplasia, type Maroteaux | AR | NPRB |

| Dysplasia with Prominent Membranous Bone Involvement | ||

| Cleidocranial dysplasia | AD | CBFA1 |

| Bent Bone Dysplasias | ||

| Campomelic dysplasia | AD | SOX9 |

| Stüve-Wiedemann dysplasia | AR | LIFR |

| Multiple Dislocations with Dysplasias | ||

| Desbuquois syndrome | AR | CANT1 |

| Pseudodiastrophic dysplasia | AR | Unknown |

| Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia with joint laxity | AR | Unknown |

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; CATSHL, camptodactyly, tall stature, and hearing loss syndrome; OSMED, otospondylometaepiphyseal dysplasia; SADDAN, severe achondroplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans; TRPV4, transient receptor potential vanilloid 4; XLR, X-linked recessive; XLD, X-linked dominant.

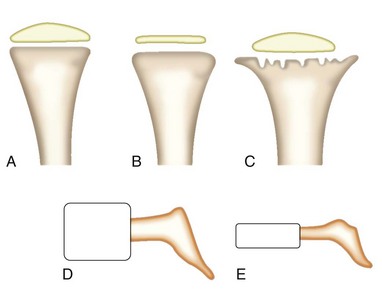

The most widely used method for differentiating the skeletal disorders has been through the detection of skeletal radiographic abnormalities. Radiographic classifications are based on the different parts of the long bones that are abnormal (epiphyses, metaphyses, and diaphyses) (Figure 105-1). These epiphyseal, metaphyseal, and diaphyseal disorders can be differentiated further depending on whether or not the spine is involved (spondyloepiphyseal, spondylometaphyseal, or spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasias). The classes of these disorders can be differentiated further into distinct disorders on the basis of other clinical and radiographic findings.

Clinical Evaluation and Features

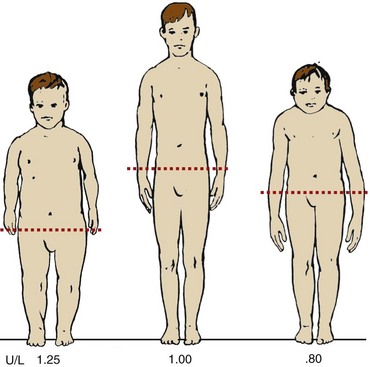

A disproportionate body habitus may not be immediately visible on physical examination. Anthropometric dimensions such as upper-to-lower segment (U/L) ratio, sitting height, and arm span must be measured when considering the possibility of a skeletal dysplasia and should be measured in centimeters. Sitting height is an accurate measurement of head and trunk length, but it requires special equipment for precise measurements. U/L ratios are easy to obtain and provide an accurate measurement of proportion. The lower segment is measured from the symphysis pubis to the floor at the inside of the heel. The upper segment is measured by subtracting the lower segment measurement from the total height. McKusick14 has published standard U/L segment ratios for whites and African-Americans across ages. An average-height white child 8 to 10 years old has a U/L segment ratio of approximately 1 and as an adult has a U/L segment ratio of 0.95. Individuals presenting with disproportionate short stature have altered U/L segment ratios depending on whether they have short limbs, short trunk, or both. An individual with short limbs and normal trunk has an increased U/L segment ratio, and an individual with normal limbs but short trunk has a diminished U/L segment ratio (Figure 105-2). Another means of determining if there is disproportion is based on arm span measurements, which are close to total height in an average-proportioned individual. A short-limbed individual has an arm span considerably shorter than the height.

As in any disorder that has a genetic basis, it is crucial to obtain an accurate family history. This should include any history of previously affected children or parental consanguinity. The skeletal dysplasias are genetically heterogeneous and can be inherited as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked recessive, and X-linked dominant disorders, and rarer genetic mechanisms of disease including germline mosaicism, uniparental disomy, and chromosomal rearrangements have been seen.15–18 For many patients and families, accurate diagnosis and recurrence risk can have a significant impact on their reproductive decisions. Another consideration for patients with short stature is that there is increased nonrandom mating, which leads to reproductive outcomes that have been previously unknown.19,20 Homozygous achondroplasia is lethal, and many newborns who inherit two dominant mutations (compound heterozygotes) die early with severe abnormalities of the skeleton.21 It is also important to obtain an accurate history relative to the onset of short stature and whether it developed immediately in the postnatal period or was noticed at age 2 or 3. Of the 450 skeletal dysplasias, approximately 100 of them have onset in the prenatal period, but many affected individuals do not develop disproportionate short stature and joint discomfort until childhood.22,23

A detailed physical examination may reveal a diagnosis or help differentiate the most likely group of possible diagnoses. It is crucial when disproportion and short stature have been established and the limbs are involved to determine which segment is involved: upper segment (rhizomelic—humerus and femur); middle segment (mesomelic—radius, ulna, tibia, and fibula); and distal segment (acromelic—hands and feet). Numerous head and facial dysmorphisms are seen in the skeletal disorders. Affected individuals frequently have disproportionately large heads. Frontal bossing and flattened nasal bridge are characteristic of achondroplasia, one of the most common skeletal dysplasias.24 Cleft palate and micrognathia are commonly found in the type II collagen abnormalities, abnormally flattened midface with a turned-up nose is frequently found in the chondrodysplasia punctata disorders,25 and abnormal swollen pinnae are seen in diastrophic dysplasia.26 Individuals with skeletal dysplasias should be screened for ophthalmologic and hearing abnormalities because many of these disorders are associated with eye abnormalities and hearing loss.

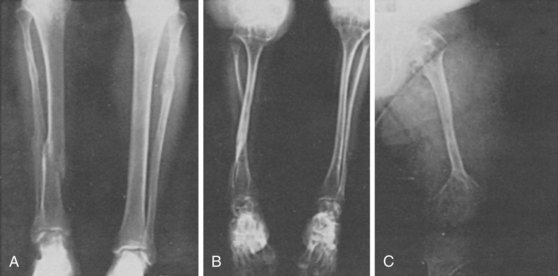

Further evaluation of the hands and feet can lead to further differentiation of these disorders. Postaxial polydactyly is characteristically found in chondroectodermal dysplasia and the short-rib polydactyly disorders (see Table 105-1). Short, hypermobile, radially displaced thumbs are seen in diastrophic dysplasia. Nails can be abnormally hypoplastic in chondroectodermal dysplasia and short and broad in cartilage hair hypoplasia. Clubfeet may be seen in many disorders including Kneist dysplasia, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita, Larsen syndrome, varying forms of osteogenesis imperfecta, and diastrophic dysplasia. Bone fractures occur most commonly in two types of disorders—those that result from undermineralized bone (OI, hypophosphatasia, achondrogenesis IA), or those that result from overmineralized bone (osteopetrosis syndromes and dysosteosclerosis).

Diagnosis and Testing

After obtaining a thorough family history and physical examination, the next step is to obtain a full set of skeletal radiographs. A full series of skeletal views includes anterior, lateral, and Towne views of the skull; anterior and lateral views of the entire spine; and anteroposterior views of the pelvis and extremities, with separate views of the hands and feet, especially after the newborn period. Most of the important clues to diagnosis are in skeletal radiographs that are obtained before puberty. When the epiphyses have fused to the metaphyses, determining the precise diagnosis can be extremely challenging. If an adult is evaluated, all attempts should be made to obtain any available childhood radiographs. Many subtle clues in these skeletal radiographs can lead to precise diagnosis. Demonstrating punctate calcifications in the areas of the epiphyses in the chondrodysplasia punctata disorders, multiple ossification centers of the calcaneus in more than 20 disorders,27 and the type of hand shortening can aid in differentiating many disorders.

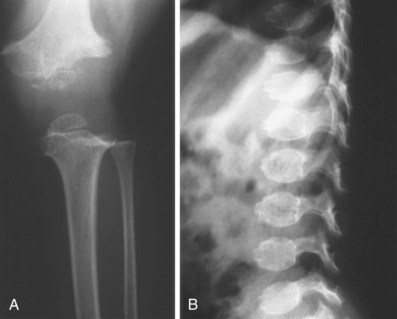

After obtaining radiographs, close attention should be paid to the specific parts of the skeleton (spine, limbs, pelvis, skull) involved and to the location of the lesions (epiphyses, metaphyses, and vertebrae) (Figure 105-3). As mentioned earlier, these radiographic abnormalities can change with age, and if available, radiographs across a few years or decades aid in diagnosis. Fractures can be seen in OI (all types) (Figure 105-4; see Table 105-1) and severe hypophosphatasia. In older individuals, fractures may be seen in disorders associated with increased mineralization such as the osteopetrosis syndromes and dysosteosclerosis. When a thorough evaluation of the radiographs reveals abnormalities, but a diagnosis still cannot be made, resources are available. The International Skeletal Dysplasia Registry and European Skeletal Dysplasia Network are available to provide diagnosis for these rare disorders.

Morphologic studies of chondro-osseous tissue have revealed specific abnormalities in many of the skeletal dysplasias.28–30 In these disorders, histologic evaluation of chondro-osseous morphology can aid in making an accurate diagnosis, and absence of histopathologic alterations can rule out diagnoses. These studies need to be done on cartilage growth plate, and although commonly performed on perinatal lethal skeletal disorders at autopsy, obtaining growth plate histology on individuals with nonlethal disorders is difficult. If affected individuals (children) are undergoing surgery, an iliac crest biopsy specimen can be evaluated.

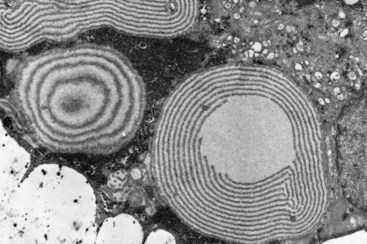

Histomorphology studies done on these disorders have led to important insights on the pathogenesis of these disorders. On morphologic grounds, the chondrodysplasias can be broadly classified into disorders (1) that have a qualitative abnormality in endochondral ossification, (2) that have abnormalities in cellular morphology, (3) that have abnormalities in matrix morphology, and (4) in which the abnormality is primarily localized to the area of chondro-osseous transformation. In thanatophoric dysplasia, there is a defect in endochondral ossification with a short, almost hypertrophic zone; shortened proliferative zone; and overgrowth of the periosteum. In pseudoachondroplasia, there is a distinct lamellar pattern (alternating electron-dense and electron-lucent lamellae) in the rough endoplasmic reticulum of chondrocytes (Figure 105-5) and a grossly abnormal matrix in diastrophic dysplasia, which leads to a characteristic ring around the chondrocytes. All of these findings are characteristic and diagnostic for these disorders and illustrate how morphology studies can have an integral part in the investigation of these disorders.

There has been significant progress in gene identification in these disorders, which has impact for affected individuals. As illustrated in Table 105-1, for disorders in which the gene is identified, molecular diagnostic testing is potentially available. Molecular diagnosis can be used to confirm a clinical and radiographic diagnosis, predict carrier status in families at risk for a recessive disorder, and, for some individuals, allow for prenatal diagnosis of at-risk fetuses. Because these are rare disorders, commercial testing is not always readily available; however, GeneTests (www.genetests.org) is a publically funded medical genetics website developed for physicians that provides information on diseases and available genetic testing.

Management and Treatment

The optimal management of this diverse set of disorders requires an understanding of the medical, skeletal, and psychosocial consequences.31 This is often best accomplished by centers that have a multidisciplinary approach, which includes adult and pediatric physicians, orthopedists, rheumatologists, otolaryngologists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, and ophthalmologists who are committed to the care of these patients.

Frequently, patients with these disorders have significant joint pain and in some cases joint limitations. Because most of these disorders result from mutations in genes crucial to cartilage function, the cartilage at the joint surfaces may not provide adequate support and cushioning function. Many of these patients seek attention for joint pain. Evaluation should include radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), when appropriate, to determine the etiology of the pain. In some disorders such as the type II collagenopathies, pseudoachondroplasia, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, and cartilage hair hypoplasia, by adulthood, so little cartilage remains at the knee or hips that joint replacement is indicated for pain relief. Lastly, overweight in adults with short stature is an ongoing issue and contributes to inactivity, loss of function, adult-onset diabetes, hypertension, and coronary disease.29

Achondroplasia

Achondroplasia is the most common of the nonlethal skeletal dysplasias (approximately 1 in 20,000) and serves as an example on how to approach these disorders. Most affected individuals are of normal intelligence, have a normal life span, and lead independent and productive lives. The mean final height in achondroplasia is 130 cm for men and 125 cm for women; specific growth charts have been developed to document and track linear growth, head circumference, and weight in these individuals.32,33

In early infancy, there is potentially serious compression of the cervicomedullary spinal cord secondary to a narrow foramen magnum, cervical canal, or both. Clinically, these infants have central apnea, sleep apnea, profound hypotonia, motor delay, emesis while forward positioned in car seats, or excessive sweating. MRI with flow studies is necessary to document the obstruction; if present, obstruction requires decompressive surgery.34 Other complications include nasal obstruction, venous distention, thoracolumbar kyphosis, and hydrocephalus in a few individuals.35

From early childhood, and as children begin to walk around 22 to 24 months, they develop several orthopedic manifestations, which include progressive bowing of the legs owing to fibular overgrowth, lumbar lordosis, and hip flexion contractures. Recurrent ear infections can lead to chronic serous otitis media and deafness. Tympanic membrane tube placement is indicated in many of these patients. Craniofacial abnormalities lead to dental malocclusion, and appropriate treatment is necessary. In adults, the main potential medical complication is impingement of the spinal root canals. This complication can be manifested by lower limb paresthesias, claudication, clonus, or bladder or bowel dysfunction. It is crucial that these complaints are addressed because without appropriate decompression surgery, spinal cord paralysis may result.36

Growth hormone has not been effective in increasing height in this disorder.33 Surgical limb lengthening has been employed successfully to increase limb length by 12 inches,37 but this technique needs to be done during the teen years and is performed over a 2-year period and is associated with complications. Recent advances in the molecular understanding underlying achondroplasia have identified molecular targets to potentially treat the disorder, thus improving height and orthopedic complications. Achondroplasia results from heterozygosity for mutations in the gene that encodes fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3). The mutation causes constitutive activation of the receptor leading to increased MAPK signaling with elevated levels of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Molecules targeted to the tyrosine kinase domain of the receptor and those that diminish ERK signaling have shown efficacy in tissue and animal models. Throughout their lives, individuals with achondroplasia and other skeletal dysplasias and their families experience various psychosocial challenges.38 These challenges can be addressed by specialized medical and social support systems. Interactions with advocacy groups such as Little People of America (www.lpaonline.org) can provide emotional support and medical information.

Biochemical and Molecular Abnormalities

Similarities in clinical and radiographic findings and histomorphology have placed bone dysplasia into families.39–41 These families share common pathophysiologic or pathway mechanisms. In recent years, there has been an explosion in understanding of the basic biology of these disorders. This explosion has resulted from the successful human genome project, which improved various methodologies including candidate gene approach, linkage analysis, positional cloning, human/mouse synteny, array comparative genomic hydridization, and massive parallel sequencing (whole exome or whole genome analyses) allowing for identification of the disease genes (see Table 105-1). With gene discovery in the vast number of these osteochondrodysplasias, these genes can be placed into several categories designed to understand their pathogenesis: (1) defects in extracellular proteins; (2) defects in metabolic pathways (enzymes, ion channels, and transporters; (3) defects in folding and degradation of macromolecules; (4) defects in hormones and signal transduction; (5) defects in nuclear proteins; (6) defects in oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes; (7) defects in RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) processing molecules; (8) defects in intracellular structural and organelle proteins; (9) microRNAs; and (10) genes of unknown function.2 There are still skeletal dysplasias for which the gene and mechanism of disease are unknown. Following are descriptions of some of the molecular mechanisms involved in the skeletal dysplasias.

Defects in Extracellular Structural Proteins

Type II Collagen and Type XI Collagen

Because type II collagen was found primarily in cartilage, the nucleus pulposus, and the vitreous of the eye, it was hypothesized that skeletal disorders with significant spine and eye abnormalities would result from defects in type II collagen. Type II collagen defects have been identified in a spectrum of disorders ranging from lethal to mild arthropathy, which include achondrogenesis II, hypochondrogenesis, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita, spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia, Strudwick type, Kniest dysplasia, Stickler syndrome, spondyloperipheral dysplasia, and “precocious” familial arthopathy. These disorders are referred to as type II collagenopathies, and they all result from heterozygosity for mutations in COL2A1.42,43 Biochemical analysis of cartilage derived from these individuals shows electrophoretically detectable abnormal type II collagen. Type I collagen is not normally present in cartilage, but in the presence of abnormal type II collagen there is increased type I collagen in the growth plate.

Mutations that result in a substitution for a triple helical glycine residue seem to be the most common type of mutation.44 There are some correlations between the location of the mutation and the disease phenotype. In spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, the glycine substitutions are scattered throughout the molecule; however, in Kniest dysplasia, the mutations are in the more amino-terminal end of the molecule.44–46 Stickler syndrome, a disorder of mild short stature, arthropathy, and high-grade myopia (see Table 105-1), is genetically heterogeneous and results from mutations in COL2A1 and COL11A1, and nonocular forms result from mutations in COL11A2.47,48 In Stickler syndrome, the COL2A1 and COL11A1 mutations tend to be nonsense mutations resulting in premature translation stop codons; however, patients with COL11A1 mutations tend to have a more severe eye phenotype and hearing loss than patients with COL2A1 mutations.

Individuals heterozygous for various COL11A2 mutations49 have a nonocular form of Stickler syndrome, consistent with the absent expression of COL11A2 in the vitreous humor. Otospondylomegaepiphyseal dysplasia is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by loss of function mutations in COL11A2.50 This disorder has radiographic similarities to Kniest dysplasia but is associated with profound sensorineural hearing loss and lack of ocular involvement. Recent discoveries have extended the spectrum of disease for type XI collagen. Autosomal recessive fibrochondrogenesis, a severe skeletal dysplasia, highly associated with lethality, results from mutations in the two genes that encode type XI, COL11A1 and COL11A2.51,52 Type II and XI collagens form a heterotypic fibril in the cartilage matrix and not surprisingly, there is significant clinical overlap in the disorders due to mutation in the genes that encode these collagens.

Cartilage Oligomeric Matrix Protein

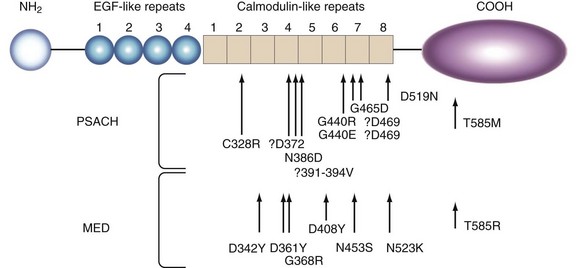

Heterozygosity for mutations in cartilage oligomeric matrix protein leads to pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia.53 Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein is a member of the thrombospondin family of proteins and consists of an epidermal growth factor domain and calcium binding, calmodulin domain.54 In pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, disease-producing mutations occur in the calmodulin domain, with a few in the globular carboxy-terminal domain (Figure 105-6). As opposed to pseudoachondroplasia, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia results from heterozygosity for mutations in numerous genes (COL9A1, COL9A2, COL9A3, and MATRILLIN3), and there is a recessive form due to mutations in the DTDST gene. Both these disorders are associated with significant early destruction of cartilage with many affected individuals undergoing hip and knee replacements at an early age.

Defects in Metabolic Pathways

Defects in metabolic pathways comprise defects in enzymes, ion channels, and transporters essential for cartilage metabolism and homeostasis. An example is the diastrophic dysplasia group (see Table 105-1), a spectrum of disorders (lethal to mild short stature) resulting from mutations in the DTDST (SLC26A2) gene. These disorders result from a varying defect in the degree of sulfate uptake or transport into chondrocytes.55 Lack of adequate intracellular sulfate affects the normal post-translational modification of proteoglycans and leads to abnormal chondrogenesis that is proportional to the degree of transporter compromise.50 Affected individuals suffer from severe degenerative joint disease.

Defects in Intracellular Structural Proteins

Intracellular proteins are ubiquitously expressed proteins; the finding that mutations in the genes encoding filamin A and filamin B produced primarily skeletal disorders was surprising.56–58 The filamins are cytoskeleton proteins involved in multicellular processes including providing structure to the cell, facilitating signal transduction and transport of small solutes, allowing communication between the intracellular and extracellular environment, and participating in cell division and motility. Defects in these genes have a profound effect on the skeleton ranging from absence of bone formation to significant joint dislocations. The mechanisms by which these mutations produce disease are unclear, though alterations in the cellular and organelle functions are beginning to be elucidated.59

Defects in Membrane Channels

Calcium homeostasis is critical for cartilage and bone.59,60 TRPV4, or transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 4, is a cation channel that mediates calcium influx in response to numerous stimuli. The importance of this channel has been demonstrated because it produces a vast spectrum of autosomal dominant skeletal disorders including lethal metatropic dysplasia, nonlethal metatropic dysplasia, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, Kozlowski type, and brachyolmia.61–63 In addition, heterozygosity for mutations in TRPV4 also causes neuromuscular diseases without notable boney manifestation that include hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy type IIC, congenital spinal muscular atrophy, and scapuloperoneal spinal muscular atrophy.64–66 The mechanism by which these mutations scattered throughout the molecule produce such divergent phenotypes is unclear but supports some common pathway in tissues of mesenchymal origin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree