9

Gastrointestinal System

At the completion of this chapter the reader should be able to do the following:

1. Describe the basic anatomy of the abdomen and gastrointestinal system

2. Perform a basic examination of the gastrointestinal system, including history, inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation

3. Recognize conditions of the gastrointestinal system that require referral

4. Describe appropriate initial management of common disorders of the gastrointestinal tract

5. Recognize conditions of the gastrointestinal system that may preclude the athlete from participation, and which symptoms are self-limiting

Overview of Anatomy and Physiology

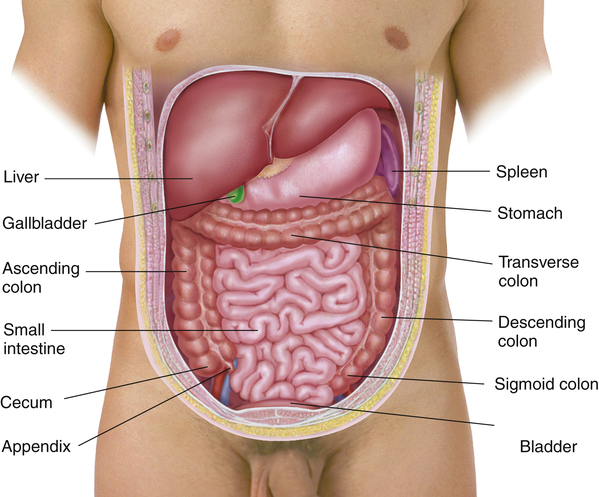

The gastrointestinal system is composed primarily of a long tube between the mouth and the anus that serves to process food and fluids (Figure 9-1). From ingestion of solids and liquids through the absorption and balancing of electrolytes and finally waste production and excretion, the alimentary tract performs several vital functions. For athletes, it is unlikely that sports will cause significant gastrointestinal problems, but rather that gastrointestinal problems are common and can affect athletic performance.

The major organs of the gastrointestinal tract start with the esophagus, which connects the mouth to the stomach via a muscular band called the gastroesophageal junction or lower esophageal sphincter. The mouth and teeth, although part of the gastrointestinal tract, are discussed in Chapter 13. Within the pouch of the stomach, hydrochloric acid and enzymes such as pepsin and gastric lipase serve to break down food for later absorption in the intestines. The stomach empties through another muscular ring, the pyloric sphincter, into the duodenum, the first portion of the small intestine.

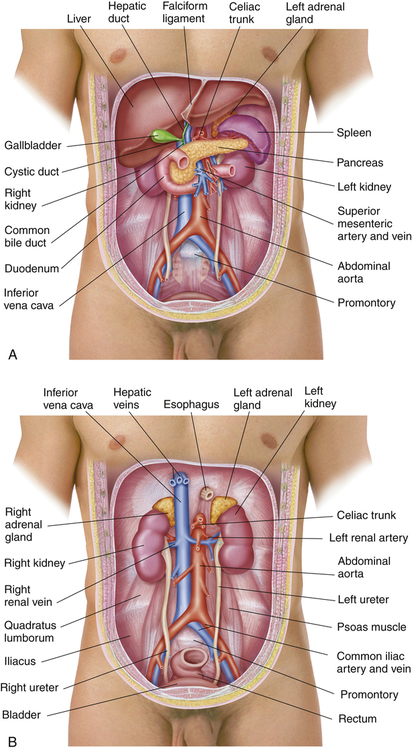

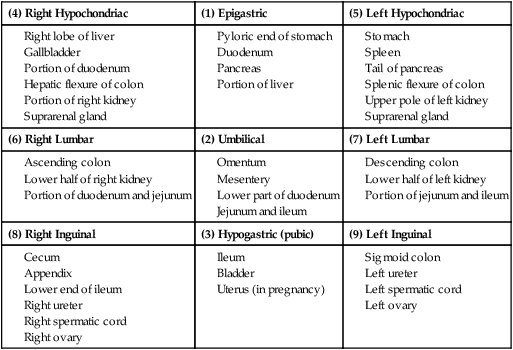

Among the many important organs in the abdomen, the gastrointestinal tract includes the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and spleen (Figure 9-2, A) as well as the kidneys and related structures (Figure 9-2, B). Each of these essential organs helps digestive and absorptive functions of the gastrointestinal system.

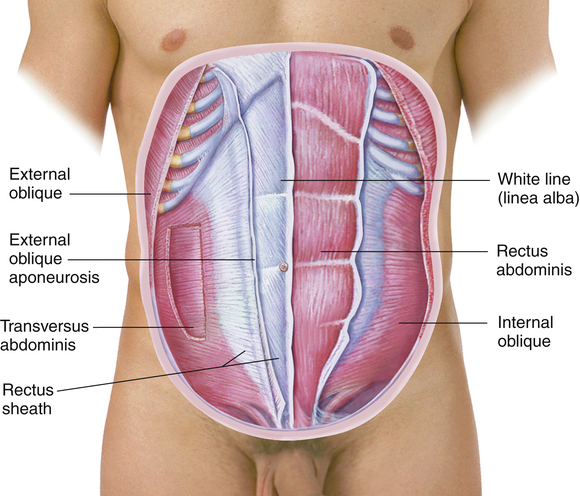

The rectus abdominis muscle and the internal and external oblique muscles serve to protect the organs of the abdominal cavity (Figure 9-3). Just like muscles elsewhere in the body, they can be injured by overuse, acute strain, or contusions. For an athlete with abdominal pain, distinguishing whether the pain is from the internal organs or the overlying muscles is important. Sometimes this distinction can be difficult, or there may be problems with both.

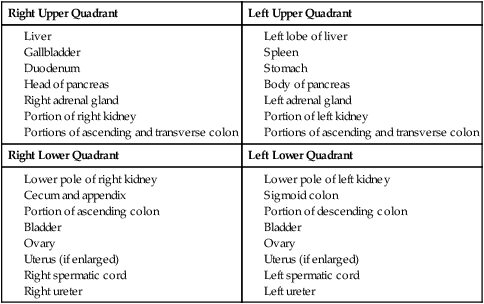

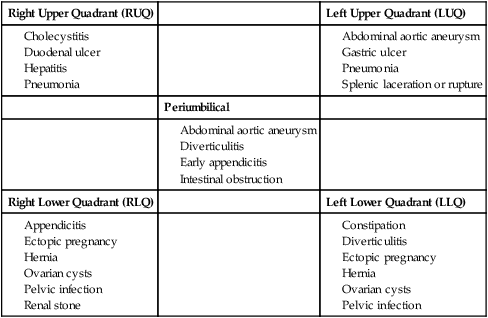

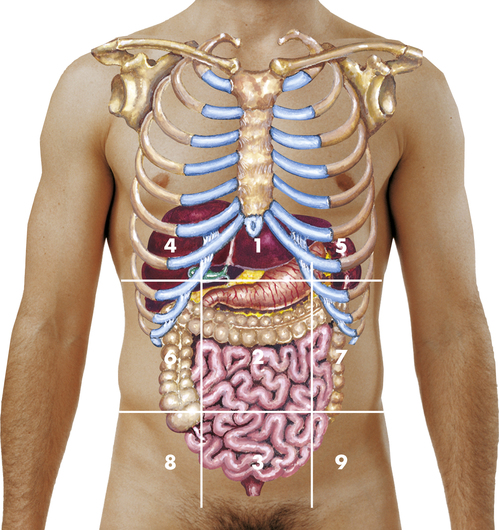

When referring to the abdomen, clinicians will typically divide it into quadrants. The midline extends from the center of the sternum through the pubic bone, and the horizontal line extends through the umbilicus. This creates right and left upper and lower quadrants, commonly referred to as RUQ, LUQ, RLQ, and LLQ. This distinction becomes important and helpful in diagnosing many conditions1 (Boxes 9-1 and 9-2). Appendicitis, for example, will typically cause RLQ pain, whereas constipation can cause LLQ pain (Box 9-3). Other clinicians may use the nine-region classification, which uses two imaginary horizontal lines and vertical lines to divide the abdomen into regions (Figure 9-4).

Pathological Conditions

General Evaluation of Abdominal Pain

The patient with abdominal pain may not have a problem with the gastrointestinal tract at all. Many possible conditions, including diseases of the heart, lungs, kidneys, and musculoskeletal system, can present as “abdominal pain” (Box 9-4). For female patients, it is important to obtain an appropriate menstrual cycle history. Pain that is perceived as being abdominal may be from the reproductive system, such as ovarian cysts, menstrual cramps, pelvic infections, or complications of pregnancy. Box 9-5 gives several key questions to ask in the evaluation of abdominal conditions.

As with other conditions, the examiner must determine whether there was any trauma involved and the details of that injury. A past medical history or family history of gastrointestinal problems can also help in the diagnosis, as can social history factors, such as alcohol intake.2 Signs or symptoms that may indicate a severe or life-threatening condition constitute red flags with abdominal pain. Beyond the obvious issues such as unstable vital signs or altered mental status that are always red flags, these findings are serious enough that a physician should be contacted immediately, or the patient should be taken to an emergency department.

Auscultation is always performed before palpation in the examination of the abdomen. In the examination of the heart and lungs, palpation is done before auscultation; however, palpation of the abdomen may create abdominal sounds that were not there before palpation. Auscultation should reveal the normal clicks and gurgling of bowel sounds that may be heard anywhere from a few times to dozens of times every minute. Chapter 2 covers use of the stethoscope and basic auscultation techniques. The examiner needs to be alert to abnormal sounds, such as high-pitched tinkling sounds or rushing water sounds, as well as the potentially absent sounds that can indicate intraabdominal pathology (Figure 9-5). Some patients may have quieter abdomens; bowel sounds are not considered absent until the examiner has listened continuously for 5 minutes with no sound heard.

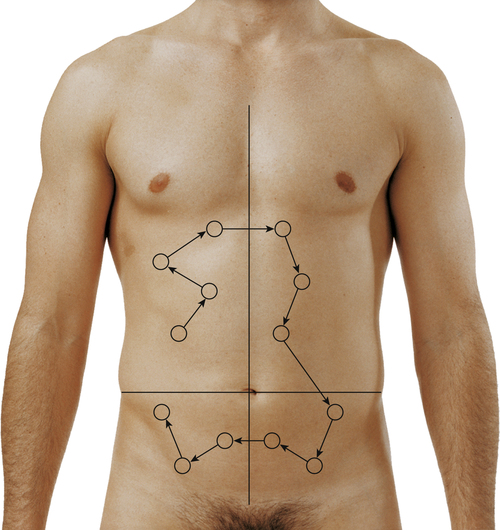

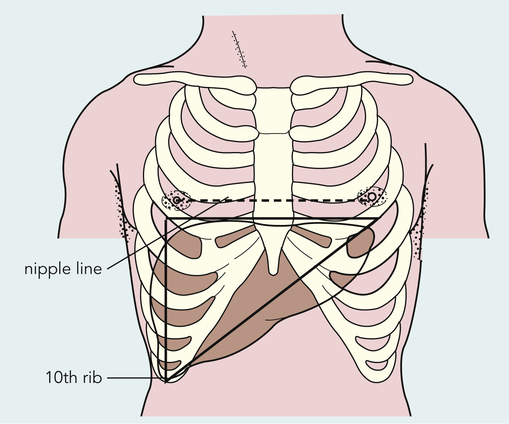

Percussion is a skill that requires considerable practice and is not covered in detail in this book. It may be used to assess the size and density of abdominal organs or to detect the presence of air or fluid in the abdominal cavity. In general, the examination follows a standard sequence for abdominal percussion (Figure 9-6) or percussion to determine size of the liver (Figure 9-7). As indicated in Chapter 2, percussion may be direct or indirect.

The examiner should practice percussing normal tympanic and dull sounds of the four quadrants exhibited by various positions of percussion. Tympany is the predominant sound throughout the abdomen and hollow organs because of the air contained in the stomach and intestines (Table 9-1). A dull sound is present over solid masses adjacent to hollow organs.

TABLE 9-1

Percussion Notes of the Abdomen

| Sound | Description | Location |

| Tympany | Musical note of higher pitch than resonance | Over air-filled viscera |

| Hyperresonance | Pitch lies between that of tympany and resonance | Base of left lung |

| Resonance | Sustained note of moderate pitch | Over lung tissue and sometimes over the abdomen |

| Dullness | Short, high-pitched note with little resonance | Over solid organs adjacent to air-filled structures |

From Seidel HM, Ball JW, Dains JE, et al: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 6, St. Louis, 2006, Mosby, p 538.

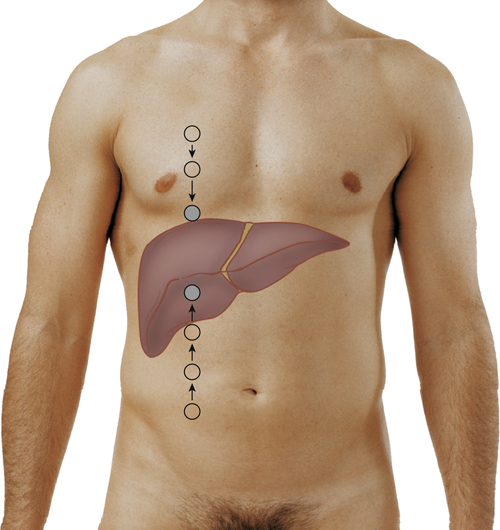

Examiners use indirect percussion to tell when they are directly over solid organs or hollow organs of the abdomen. A change in sound from tympanic to dull is easier to detect, so examiners usually start over an area known to be normally tympanic. Percussion is most commonly performed to tell the size of the liver and spleen. It is important to understand the surface anatomy of the liver (Figure 9-8) in order to assess the liver through indirect percussion (Figure 9-9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree