112 Fungal Infections of Bones and Joints

Fungi are an infrequent but clinically important cause of bone and joint infections.

These infections are often indolent in onset and may masquerade as other disorders.

Fungal infection is a relatively infrequent but important cause of osteomyelitis and arthritis. Fungal diseases that commonly cause osteomyelitis include coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, candidiasis, and sporotrichosis (Table 112-1). Fungal arthritis is less common and is most often associated with sporotrichosis, cryptococcosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, candidiasis, and, occasionally, other species. The epidemiology of these fungal infections, their musculoskeletal presentations, and their treatment are considered in this chapter.

Table 112-1 Disseminated Fungal Infections Reported with Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonist Therapy

| Organism | References |

|---|---|

| Aspergillosis | 1, 49, 101 |

| Candidiasis | 1 |

| Coccidioidomycosis | 99, 100 |

| Cryptococcosis | 29, 102 |

| Histoplasmosis | 69, 72 |

| Pneumocystosis | 110, 119 |

| Scedosporiosis | 103 |

| Sporotrichosis | 49 |

The epidemiology and clinical features of individual deep mycoses may suggest the diagnosis in some cases, but their indolent presentation, which often resembles that of other noninfectious diseases, may be misleading. Travel and immigration have blurred their geographic localization. Infection may be acute and overwhelming in immunocompromised patients, for whom disseminated fungal infections are a major risk. Anticytokine and other immunosuppressive treatments for rheumatic diseases, particularly those targeting tumor necrosis factor (TNF), are associated with disseminated fungal infection,1,2 as are acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), pregnancy, and treatments for transplantation and malignancies,3 in some cases. For rheumatologists, disseminated fungal infections are an important diagnostic consideration in some patients and must be considered before starting biologic treatments in those at risk; they may also complicate the clinical course of other arthritides. The presentation of fungal infections as a consequence of rheumatic disease therapy will also be considered in this chapter.

Fungal infections are generally diagnosed by histologic examination or culture of involved tissues. Improved biopsy techniques may assist the diagnosis, provided the possibility of fungal infection is considered and proper studies are requested. Synovial fluid leukocyte counts and culture results vary among fungal infections and in individual cases and may be misleading. Serologic testing may also assist in diagnosing and staging several fungal infections. Detecting fungal antigens and DNA in blood and tissue is now possible in some cases, but the clinical use of these methods is still under investigation.4

Coccidioidomycosis

The soil fungi Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii generally cause a primary respiratory illness after spores are inhaled. A self-limited acute pneumonia may result, associated with systemic manifestations such as arthralgia and erythema nodosum (valley fever), but infection is often unapparent and only infrequently becomes chronic or disseminated.5 Coccidioidomycosis is endemic to the southwestern United States and areas of Central and South America, but cases are increasingly diagnosed in nonendemic areas because of travel, infection from fomites, and reactivation of remote infection. Cases increase when soil is disturbed and in windy conditions. Direct human-to-human transmission is rare. Extrapulmonary infection is almost always caused by hematogenous spread from an initial pulmonary focus. The bones and joints are frequent sites of dissemination, particularly in immunocompromised hosts.

Septic arthritis of the knee is common, generally arising from direct infection of the synovium. Other joint infections are caused by spread from a contiguous osteomyelitis involving the vertebrae, wrists, hands, ankles, feet, pelvis, and long bones.6 The onset is characterized by gradually increasing pain and joint stiffness, with little swelling but early radiographic changes. In one series, arthritis was the only manifestation of disseminated coccidioidomycosis in 51 of 57 patients and was an aspect of more generalized disease in the remaining 6 patients.7

Diagnostic confusion is common in osteoarticular coccidioidomycosis because of the delayed dissemination (months to years) after primary infection and because of atypical clinical presentations. The criteria for diagnosis include compatible clinical features, serologic studies, histologic examination, and culture. Early infections, often before systemic spread, are associated with a positive antibody precipitin test that detects immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibody. Complement fixation serologic values detecting IgG antibodies are in a range indicative of disseminated disease in a majority of patients and show a significant decrease with effective treatment. Serologic testing for Coccidioides may have negative results early in the infection and in immunosuppressed patients. A specific enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to Coccidioides galactomannan antigen in urine has shown promise in the diagnosis of severe coccidioidomycosis infection.8,9 The definitive diagnosis is most commonly made by the demonstration of granulomatous synovitis and typical spherules in a biopsy specimen, confirmed in some cases by positive culture and direct amplification testing. Synovial fluid, when obtainable, does not necessarily demonstrate septic leukocyte counts and may have a lymphocyte predominance. Synovial fluid is rarely culture positive; culture of synovial tissue may be more helpful. Radioisotope bone scans may be helpful to identify areas of infection.10

With early diagnosis of effusive synovitis, antifungal treatment alone is appropriate. Treatment is usually initiated with oral azole antifungal agents, most commonly fluconazole or itraconazole.11 Amphotericin B is recommended for alternative therapy, especially if lesions are appearing to worsen rapidly and are in particularly critical locations such as in vertebral osteomyelitis. Lipid formulations of amphotericin B have demonstrated less nephrotoxicity and infusion-related side effects than conventional deoxycholate amphotericin B and may be given at doses higher than those tolerated with conventional amphotericin, but they have never been formally studied in clinical trials. With more widely disseminated infection or involvement of critical areas such as the spine, as well as in high-risk hosts, the choice and duration of treatments are often complicated. Factors that favor surgical intervention are large size of abscesses, progressive enlargement of abscesses or destructive lesions, presence of bony sequestrations, instability of the spine, or impingement on critical organs or tissues (e.g., epidural abscess compressing the spinal cord).7,12,13 Newer antifungal agents such as voriconazole and posaconazole show promise as alternative therapy.11,14–16 Long-term prophylaxis with fluconazole can limit the risk for reactivation in immunosuppressed patients.

Coccidioidal synovitis may also occur as a consequence of immune complex–mediated inflammation, a presentation that may complicate either primary pulmonary or disseminated disease and is typically polyarticular. It is accompanied by fever, erythema nodosum or multiforme, eosinophilia, and hilar adenopathy. It abates in 2 to 4 weeks.5,17

Blastomycosis

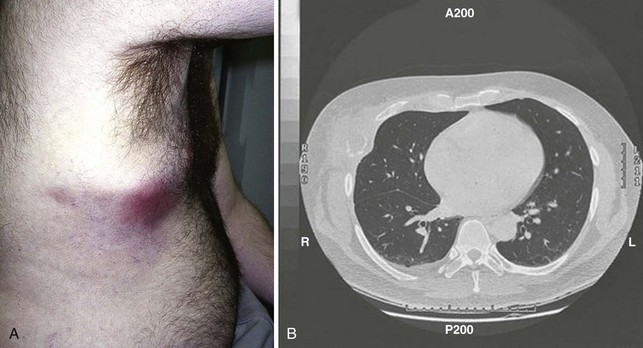

Blastomycosis, caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, is endemic in the north-central and southern United States. Infection most commonly produces sporadic or clustered cases of pulmonary disease and is induced by exposure to soil or dust containing decomposed wood and, presumably, contaminated with the organism.18 Affected individuals do not appear to have any distinguishing or predisposing characteristics except for exposure to the organism during work or recreation. Clinical presentation includes high fever and other constitutional symptoms, pulmonary and skin involvement, and a significant mortality rate; leukocytosis and an elevated sedimentation rate are frequently seen.19 Bone pain, swelling, and soft tissue abscesses are the most common manifestations of osteoarticular disease.20 Hematogenous dissemination is common; skin disease and osteoarticular disease occur most frequently. Bone involvement occurs in 25% to 60% of disseminated cases, and arthritis is estimated to occur in 3% to 5%.19 In a study of 45 patients with skeletal blastomycosis, 41 had osteomyelitis while 12 presented with septic arthritis.20 The skeletal areas most commonly affected are the long bones, vertebrae, and ribs (Figure 112-1).21–23

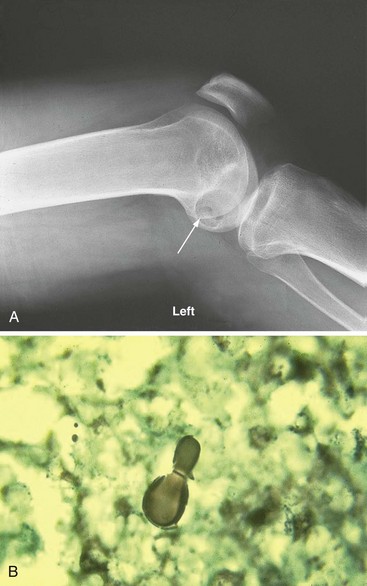

Arthritis is usually monoarticular in the knee, ankle, or elbow but may rarely be polyarticular.19,24 Joint infection is an isolated skeletal disorder in only a few cases; joint radiographs more commonly show punched-out bone lesions (Figure 112-2A). Synovial fluid is commonly purulent, and organisms are evident on microscopic examination, as well as by culture. The synovial histologic examination shows epithelioid granulomas with budding yeast forms (Figure 112-2B). The diagnosis is also commonly made from involved nonarticular sites. Urinary antigen testing appears to be sensitive but may be falsely positive in patients with other endemic fungal infections.25 For moderately severe or severe disease, treatment with amphotericin B for 1 to 2 weeks or until improvement is noted, followed by oral itraconazole for a total of at least 12 months, is recommended. For mild to moderate disease, oral itraconazole for 12 months is recommended. Serum levels of itraconazole should be determined after the patient has been on treatment for at least 2 weeks, to ensure adequate drug exposure.18,26–28

Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcus neoformans, the fungus causing cryptococcosis, is geographically ubiquitous and is found in pigeon feces; a related species, Cryptococcus gattii, is associated with certain types of eucalyptus trees in tropical climates and has been associated with an ongoing outbreak of disease on Vancouver Island and surrounding areas of Canada and the northwestern United States. It is a common pathogen only in association with defects in cell-mediated host defense including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, transplantation, lymphoreticular malignant neoplasms, TNF antagonist treatment,29,30 and corticosteroid therapy.

Cryptococcosis varies in acuity, usually affecting the lungs in its primary form, but it sometimes disseminates hematogenously to a wide variety of sites including the central nervous system and skin. Although bone infection is common, causing osteolytic lesions in 5% to 10% of cases, articular involvement is rarely reported.31,32 Bone lesions may be confused with metastatic neoplasm (Figure 112-3).

Cryptococcal arthritis is an indolent monoarticular arthritis in about 60% of reported cases and a polyarthritis in the remainder.33,34 The knee is most commonly involved. A single case of tenosynovitis with carpal tunnel syndrome has been recognized. The majority of cases reported from the pre-AIDS era also demonstrated radiographic evidence of periarticular osteomyelitis. These patients were young adults, did not have debilitating disease or other evidence of dissemination, and had pulmonary involvement in only 50% of cases. Synovial tissue showed acute and chronic synovitis, multinucleate giant cells, prominent granuloma formation, and large numbers of budding yeast with special stains. Most recently reported cases are associated with immunosuppression and disseminated infection. Interestingly, osteoarticular cryptococcal infections have been linked to sarcoidosis, although it is unclear whether this association relates to the immunologic impact of the sarcoidosis or to the immunosuppressive therapies used to treat it.35 Serum cryptococcal antigen testing appears to be sensitive, in part because osteoarticular infection results from hematogenous dissemination. The choice of treatment for cryptococcal disease depends on both the anatomic sites of involvement and the host’s immune status, with amphotericin B and fluconazole being considered most effective.34,36 5-Flucytosine is typically added to amphotericin B or fluconazole for the first 2 to 4 weeks (induction therapy) in cases of severe cryptococcal infection.37

Candidiasis

Candida species are widely distributed yeasts. Candida albicans is a normal commensal of humans, and other species can probably live in nonanimate environments such as soil. Since the advent of antibiotic therapy in the 1940s, and related to the common use of immunosuppression and parenteral lines, candidiasis has been responsible for an increasing incidence of mucocutaneous and deep-organ infections.38 Osteomyelitis, though rarely reported, is a potentially serious complication of hematogenous dissemination in both adults and children.39,40 It may also occur from direct tissue inoculation during surgery or by injection of contaminated heroin,41 and bone infection may emerge after successful amphotericin B treatment of other sites. Infection is commonly located in two adjacent vertebrae or in a single long bone. Surgical inoculation has occurred in the sternum, spine, and mandible. A few patients have had multiple sites of involvement. Candidal prosthetic joint infections may also occur as a late consequence of total joint replacement.42

The clinical presentation is localized pain. Other symptoms and laboratory abnormalities vary. Bone changes of osteomyelitis are commonly demonstrated in radiographs of the symptomatic site. The diagnosis is established when culture of involved bone obtained by either open or needle biopsy has identified a variety of Candida species. Use of direct amplification testing has been reported.43 Treatment with azoles (fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, or posaconazole); echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin, or anidulafungin); or amphotericin B formulations may be effective.44,45 Species identification and susceptibility testing assist antifungal therapy selection. For example, Candida glabrata frequently demonstrate reduced susceptibility to azole antifungal agents and amphotericin but remain susceptible to echinocandins; Candida krusei are often resistant to azoles and may show reduced susceptibility to amphotericin but also remain susceptible to echinocandins; Candida lusitaniae are often resistant to amphotericin; and Candida parapsilosis may demonstrate reduced susceptibility to echinocandins.45 The use of surgical débridement must be individualized. With vertebral involvement but no neurologic complications, medication alone has been effective.

Candidiasis is an uncommon cause of monoarticular arthritis.46 C. albicans is the most common pathogen, although septic arthritis due to other candidal species has been reported.47 Reported cases commonly involve a knee, occur in the context of multifocal extra-articular Candida infection, and are accompanied by constitutional symptoms. Both children and adults have been affected. Predisposing conditions include gastrointestinal and pulmonary disorders, narcotic addiction, intravenous catheters, leukopenia, immunosuppressive treatment (including TNF antagonists), broad-spectrum antibiotics, and corticosteroids. Some involved joints were previously affected by arthritis, and infection has followed arthrocentesis in isolated cases. In most cases, radiographs reveal coincident osteomyelitis. Synovial fluid leukocyte counts may vary; Candida species have been cultured from synovial fluid in all cases but are not commonly identified on smear. Histologic studies of synovium show nonspecific chronic inflammation rather than granulomas.

Sporotrichosis

Sporotrichosis is caused by Sporothrix schenckii, a saprophyte found widely in soil and plants. Infection in humans occurs through inoculation of the skin or, rarely, inhalation into the respiratory tract; it is a source of infection among agricultural workers in tropical and subtropical areas. It most commonly involves the skin and lymphatics but may disseminate from the lungs to the central nervous system, eyes, bones, and joints.48 In immunocompetent hosts, a single site is typically involved; in immunocompromised hosts including patients on anticytokine therapy, multifocal disease may occur.49

In contrast to the relatively common occurrence of skin infection, articular sporotrichosis is a rare disorder.50,51 In 84% of patients in one series, there was no accompanying skin involvement, suggesting entry through the lungs. Sporotrichosis most often occurs in individuals with a chronic illness that alters host defense such as alcoholism or a myeloproliferative disorder. Sporothrix arthritis is most often indolent and infects a single joint or multiple joints in equal proportions. The knee, hand, wrist, elbow, and shoulder are most frequently involved; hand and wrist involvement distinguishes this from other fungal arthritides. Articular infection shows a propensity to spread to adjacent soft tissues, forming draining sinuses. Constitutional symptoms are unusual.

Radiographic changes vary from juxta-articular osteopenia to the commonly observed punched-out bone lesions. When it can be obtained, synovial fluid is inflammatory. Synovitis is characterized on gross evaluation by destructive pannus and on microscopic examination by granulomatous histologic features or, less frequently, by nonspecific inflammation. Organisms are difficult to identify in tissue, and the diagnosis is often made by positive culture of joint fluid or involved tissue. Incubation at room temperature assists growth of the mycelial phase of S. schenckii. Serologic testing is not useful in the diagnosis of sporotrichosis. In a small number of cases, sporotrichosis may disseminate to cause a potentially fatal infection characterized by low-grade fever, weight loss, anemia, osteolytic bone lesions, arthritis, skin lesions, and involvement of the eyes and central nervous system.52–55 These infections occur in immunosuppressed patients with either hematologic malignancies or HIV infection.

In 44 cases reported in 1979, treatment was optimal with combined joint débridement and high-dose intravenous amphotericin B (11 of 11 cured) and slightly less effective with amphotericin alone (14 of 19 cured).50 More recently, itraconazole has proven effective for initial therapy of most patients,56 with amphotericin B being reserved for those with extensive involvement and for itraconazole failures. In contrast, fluconazole has demonstrated only modest success in osteoarticular sporotrichosis.57,58 Long-term suppressive therapy with itraconazole may be required for patients with AIDS.56