CHAPTER 16 Facial injury

Ocular injury

Surface anatomy and basic muscle examination of the eye are shown in Treatment note 16.1.

Treatment note 16.1 Surface examination of the eye

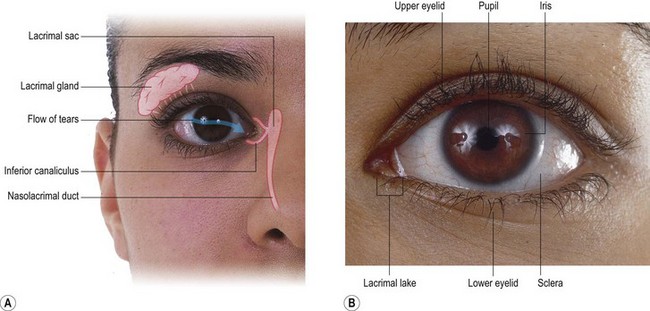

The sclera of the eye is the white portion at the side of the iris. It continues as the cornea which is the clear central region of the eye through which the iris (eye colour) and pupil (black centre) may be seen. At the medial corner of the eye is the lacrimal lake in which the tears collect. Tears originate in the lacrimal gland on the upper outer aspect of the orbit and flow downwards and inwards across the eye to hydrate the cornea. Once collected in the lacrimal lake, the tears drain into the nasal cavity. The eye and lacrimal apparatus is shown in Fig. 16.1.

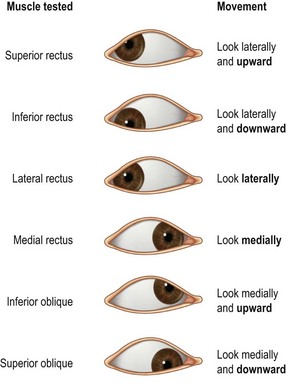

Movement of the eye is controlled by the extrinsic or extraocular muscles, and each muscle may be tested by asking the patient to look in a particular direction (Fig. 16.2). This is most commonly carried out by having the patient follow the therapist’s finger while keeping his/her head in a fixed position. The examination highlights abnormality of the third (oculomotor), fourth (trochlear) and sixth (abducent) cranial nerves, which supply the muscles.

The following signs and symptoms are indications for immediate ophthalmology referral (Brukner and Khan, 2007):

Eye injuries may arise from collisions in which a finger or elbow goes into the eye. Small balls (squash balls, shuttlecock) may cause ocular damage, while larger balls (cricket or hockey) are more likely to cause orbital fractures. Mud, grit or stone chips can enter the eye and cause both irritation and damage. It is interesting to note the speed at which a ball may move. In squash, the ball can travel at 140 m.p.h., in cricket at 110 m.p.h. and in football 35–75 m.p.h. (Reid, 1992). A small object travelling at these speeds obviously creates considerable force and potential for damage. This is borne out by the sad fact that over 10% of eye injuries in sport result in blindness in that eye (Pashby, 1986).

Following injury, basic vision assessment should be carried out and if any abnormalities are detected the athlete should be referred to an ophthalmologist. A distance chart (placed 6 m from the subject) and a near vision chart (35 cm from the eyes) should be used. Failure to read the 20/40 line on either chart is a reason for referral (Ellis, 1987). Visual fields are tested in all four quadrants. One eye is covered, and the athlete should look into the examiner’s eyes. The examiner moves a finger to the edge of the visual field in both horizontal and vertical directions until the athlete loses sight of it. Decreased visual acuity or loss of the visual field in one area warrants referral (Ellis, 1987).

Pupil reaction may be tested with a small pen torch. Pupil size, shape and speed of reaction are noted. Pupil dilation in reaction to illumination requires immediate referral, as does any irregularity in pupil shape and an inability to clear blurring of vision by blinking. A number of common eye symptoms and possible causes are listed in Table 16.1.

Table 16.1 Common eye symptoms encountered in sport

| Symptoms | Possible cause |

|---|---|

| Eye itself | |

| Itching | Dry eyes, fatigue, allergies |

| Tears | Hypersecretion of tears, blocked drainage, emotional state |

| Dry eyes | Decreased secretion through ageing, certain medications |

| Sandy/gritty eyes | Conjunctivitis |

| Twitching | Fibrillation of orbicularis oculi muscle |

| Eyelid heaviness | Lid oedema, fatigue |

| Blinking | Local irritation, facial tic |

| Eyelids sticking together | Inflammatory conditions of lid or conjunctiva |

| Sensation of ‘something in the eye’ | Corneal abrasion, foreign body |

| Burning | Conjunctivitis |

| Throbbing/aching | Sinusitis, iritis |

| Vision | |

| Spots infront of eyes | Usually no pathology, but if persists consider possible retinal detachment |

| Flashes | Migraine, retinal detachment |

| Glare/photophobia | Iritis, consider meningitis |

| Sudden vision distortion | Macular oedema, retinal detachment |

| Presence of shadows or dark areas | Retinal haemorrhage, retinal detachment |

Adapted from Magee (2002).

Eye protection

Sports trauma accounts for 25% of all serious ocular injuries (Jones, 1989), an even more tragic statistic when we realize that 90% of sports injuries to the eye could be prevented by wearing eye protection (Pashby, 1989). Prevention of ocular trauma comes from two sources, sports practice and eye protection.

Dental injury

Displacement of a tooth is more common when a gum shield is not worn. The displaced tooth should be washed in tepid water and replaced in the socket, taking care to put the tooth back the right way round. The athlete may hold the tooth in place by biting on a cloth or handkerchief until specialist advice can be sought. In children, a displaced tooth may be soaked in whole milk (Mackie and Warren, 1988) until help is available. The tooth should be handled by the crown to avoid further damage to the cells at its root. Good results may be expected if reimplantation is carried out within 30 minutes of trauma, but after 2 hours the prognosis is poor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree