66 Analgesic Agents in Rheumatic Disease

Numerous analgesic agents can be used in the treatment of pain related to rheumatic disease.

Numerous anticonvulsants have been studied with conflicting results. Only gabapentin and pregabalin consistently demonstrated efficacy in double-blind, placebo-controlled studies.1,2

Muscle relaxants are intended for short term use only and have not been shown to have long benefits.

Pain is the most common reason why patients seek medical attention, yet undertreatment of acute and chronic pain persists despite decades of efforts to provide clinicians with information about analgesics.3,4 A major consequence of undertreating the patient who initially presents with pain as a result of rheumatic disease is the development of chronic pain. Chronic pain has been demonstrated to have deleterious effects on many aspects of the patient’s daily life. These effects include deterioration in physical functioning, the development of psychologic distress and psychiatric disorders, and impairments in interpersonal functioning.5,6 In addition to the personal suffering it causes, chronic pain imposes a burden on society in increased health care costs, disability, and lost workdays.

Physiology of Pain Perception (the Pain Experience)

The “pain experience” involves more than just the sensation of pain. Pain activates many areas of the brain that interact, resulting in the pain experience, which will differ among individual patients. The three components of the pain experience include (1) sensory/discriminative, (2) affective/emotional, and (3) evaluative/cognitive.7,8

The main neurotransmitter in primary afferents is the excitatory amino acid glutamate. Activation of nociceptors causes the release of glutamate from presynaptic terminals in the spinal cord dorsal horn; this release acts on the ionotropic glutamate receptor amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-proprionic acid postsynaptically to cause rapid depolarization of dorsal horn neurons and, if threshold is reached, action potential discharge.9,10

Pain Classification

Pain can be mechanistically divided into four classifications: nociceptive, inflammatory, functional, and neuropathic. Nociceptive pain is transient pain in response to a noxious stimulus that activates high threshold afferents. Nociceptive pain serves a protective function. Inflammatory pain is the spontaneous hypersensitivity to pain that occurs in response to tissue damage and inflammation (e.g., postoperative pain, trauma, arthritis). Functional pain is hypersensitivity to pain resulting from abnormal central processing of normal input (e.g., pathologic irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia). Neuropathic pain is spontaneous pain and hypersensitivity to pain that occurs in association with damage to or lesions of the nervous system (e.g., peripheral neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia). Nociceptive pain and inflammatory pain are prevalent in rheumatic disease. Functional pain and neuropathic pain are probably less prevalent in rheumatic disease; however, both should always be considered because poorly controlled pain can lead to nervous system dysfunction and functional and neuropathic pain.11

Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Pain

The efficacy of analgesics is dependent on the pain mechanism. Primary analgesics are more efficacious in nociceptive and inflammatory pain, whereas adjuvant agents are more efficacious in neuropathic and functional pain. Each pain classification involves different pain mechanisms, and within each classification are multiple different pain mechanisms.12,13

Pharmacologic agents for the management of chronic pain are divided into primary analgesics, which have intrinsic analgesic properties, and adjunct analgesics, which may have primary analgesic properties in neuropathic pain but usually enhance the analgesic effects of primary analgesics when used in non-neuropathic pain syndromes. Table 66-1 summarizes these agents. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)/cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors will be discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 59).

Table 66-1 Analgesic Options to Treat Chronic Pain

| Primary Analgesics | Adjunct Analgesics |

|---|---|

Opioids

Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of the opioids in a variety of chronic pain states, including neuropathic and non-neuropathic. However, studies to document long-term efficacy have not been conducted. Long-term opioid therapy to treat chronic pain remains controversial. Over the last century, the pendulum has swung back and forth with regard to the use of the opioids to treat pain. In the mid 20th century, opioids were limited because of fears of addiction and diversion. In the late 20th century, the pendulum went to the other side with liberal use of opioids to treat chronic pain. With the turn of the 21st century, the pendulum is moving back toward the middle with recognition of the importance of opioids in chronic pain management but an understanding of the need to balance these benefits with risks. Recently published guidelines acknowledge that opioid analgesics have an important role in pain management, and that underuse of these agents may contribute to suboptimal pain management.14 However, these guidelines also acknowledge that abuse of prescription opioids has become an epidemic, with dramatic increases seen in the United States. Therefore, a set of Universal Precautions have been developed as a guide to help the physician who prescribes opioids15 (Table 66-2).

Table 66-2 Universal Precautions for Long-term Opioid Use to Treat Pain

After conservative treatments, including nonopioids, have failed to control the patient’s pain, an opioid should be considered. In general, a short-acting weak opioid such as hydrocodone or codeine should be used first. If the patient is requiring more than three or four short-acting weak opioids per day, consider converting to a long-acting opioid. Controlled-release or long-acting opioids not only provide convenience to patients by reducing the number of daily doses required, they also provide a pharmacokinetic profile that results in reduced serum level peaks and troughs, and thereby an improvement in the consistency of effective analgesia and a potential reduction in opioid-related side effects that are often correlated with high peak serum levels. When converting to a long-acting opioid, access to a short-acting opioid for breakthrough pain can be continued, but monitored and controlled. Evaluation by a pain specialist may be considered when morphine equianalgesic dosages exceed 90 mg/day. The benefits of levels higher than 180 mg/day have not been established, and recent evidence suggests a significant increase in morbidity and mortality when doses exceed 100 mg/day.16

Opiate Receptor Classes

Early work by Martin and associates led to the postulation of three opiate receptors: mu, kappa, and sigma.17,18 Later studies by Kosterlitz and colleagues led to the identification of the delta opioid receptor.19 With the exception of the sigma receptor, all of the opiate receptors are responsible for opioid-induced analgesia. Opioid receptors are mediated through a G protein, leading to a cascade of events that typically inhibit neuron activation.20 Persistent activation of G protein–coupled receptors typically results in progressive loss of effect, known as tolerance (discussed later).

Opiate Receptor Distribution and Mechanisms of Opioid-Induced Analgesia

Numerous sites in the brain have MORs. Activation of receptors located in the mesencephalic periaqueductal gray (PAG) appears to be the most important cause of opioid-induced analgesia. MOR agonists block release of the inhibitory transmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) from tonically active PAG systems that regulate activity in projections from the PAG to the medulla. This results in an increase in PAG outflow to the medulla, leading to activation of medullospinal projections and release of noradrenaline or serotonin at the level of the spinal dorsal horn. This release can attenuate dorsal horn excitability and analgesia. PAG activation can also increase the excitability of the dorsal raphe and the locus coeruleus, from which ascending serotonergic and noradrenergic projections originate to project to the limbic forebrain, leading to the euphoric effects sometimes experienced with systemic MOR agonists.21

In the spinal cord, MOR agonists are limited for the most part to the substantia gelatinosa of the superficial dorsal horn, the region in which small, high-threshold sensory afferents terminate. Most of these opiate receptors are located presynaptically and postsynaptically on small peptidergic primary afferent C fibers. Presynaptic activation of the MOR prevents the opening of voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels, thereby preventing transmitter release. Postsynaptic activation of the MOR increases potassium conductance, resulting in hyperpolarization and reduced excitation induced by the presynaptic release of glutamate.22 The ability of spinal opiates to reduce the release of excitatory neurotransmitters from C fibers presynaptically and to decrease the excitability of dorsal horn neurons postsynaptically is believed to account for powerful and selective effects upon spinal nociceptive processing. In humans, an extensive literature indicates that a variety of opiates delivered spinally (intrathecally or epidurally) can induce a powerful analgesia.22

Systemic delivery of the opioids will reduce nociceptive pain through a central mechanism located in the brain and spinal cord, as described previously, whereas the peripheral application has no effect. However, under conditions of inflammation, which result in an exaggerated pain response (hyperalgesia), the peripheral application of the opioids will reduce the hyperalgesia. This action is believed to be mediated by opiate receptors on the peripheral terminals of small primary afferents that become active under inflammatory conditions. Whether the effects are uniquely on the afferent terminal or on inflammatory cells that release products that sensitize the nerve terminal is not known.23

Tolerance

The mechanism of opioid tolerance is controversial. Apparent opioid tolerance may be an indication of disease progression with a resultant increase in pain intensity; this is the first event that should be ruled out before true tolerance is assumed. Many cellular mechanisms can lead to tolerance. First, long-term opioid exposure can lead to receptor internalization, dephosphorylation, and desensitization. Second, exposure to high doses of opioids can lead to an increase in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), activation of bulbospinal pathways, and glutamate receptor phosphorylation, producing an excitatory state (opioid-induced hyperalgesia).24,25 An incomplete cross-tolerance occurs between the various opioids, and when tolerance develops to one opioid, switching to another opioid can result in an increased effect.

Physical Dependence

Opioid withdrawal is manifested by significant somatomotor and autonomic outflow (reflected by agitation, hyperalgesia, hyperthermia, hypertension, diarrhea, pupillary dilation, and release of virtually all pituitary and adrenomedullary hormones) and by affective symptoms (dysphoria, anxiety, and depression).26 Opioid withdrawal can be minimized by slowly tapering the opioid. These phenomena are considered to be highly aversive and motivate the drug recipient to make robust efforts to avoid the withdrawal state. Initially, drug addicts are driven to repeated doses of opioids owing to the euphoric effects. However, over time, the euphoric effects are lessened, and addicts are driven to continue use to avoid withdrawal.

Addiction

Evaluating for addiction in a patient who is prescribed long-term opioids for pain control is often problematic. This risk of opioid addiction and misuse can be assessed with validated questionnaires (Table 66-3).27 Although the concept of addiction may include the symptoms of physical dependence and tolerance, physical dependence or tolerance alone does not equate with addiction. In the chronic pain patient taking long-term opioids, physical dependence and tolerance should be expected, but the maladaptive behavior changes associated with addiction are not expected.28,29

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Family History (Parents and Siblings) | ||

| Alcohol abuse | _____(3*) | _____(1) |

| Illegal drug use | _____(3) | _____(2) |

| Prescription drug abuse | _____(4) | _____(4) |

| Personal History | ||

| Alcohol abuse | _____(3) | _____ (3) |

| Illegal drug use | _____(4) | _____ (4) |

| Prescription drug abuse | _____(5) | _____ (5) |

| Mental Health | ||

| Diagnosis of ADD, OCD, bipolar, schizophrenia | _____ (2) | _____ (2) |

| Diagnosis of depression | _____ (1) | _____ (1) |

| Other | ||

| Age 16-45 years | _____ (1) | _____ (1) |

| History of preadolescent sexual abuse | _____ (0) | _____ (3) |

| Total | _____ | _____ |

ADD, attention deficit disorder; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

* Numbers in parentheses indicate points. Scoring:

0-3: low risk: 6% chance of developing problematic behaviors.

4-7: moderate risk: 28% chance of developing problematic behaviors.

≥8: high risk: >90% chance of developing problematic behaviors.

Adapted from Webster LR, Webster RM: Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool, Pain Med 6:432–442, 2005.

Addiction is a behavioral pattern characterized by compulsive use of a drug and overwhelming involvement with its procurement and use in spite of potential harm. For patients with continuous pain, inadequate pain management (e.g., PRN dosing schedule, use of drugs with inadequate potency, use of dosing intervals that are too long) can lead to behavioral symptoms that mimic those seen with psychological dependence and can be mistaken for addiction termed pseudoaddiction. In the case of pseudoaddiction, problem behaviors resolve after sufficient pain relief is established. However, behaviors related to true addiction may also resolve after dose escalation. Thus, it can be difficult to distinguish pseudoaddiction from true addiction; careful evaluation and management may be required until the circumstances are sorted out30 (see Table 66-3).

Opioid Pharmacology

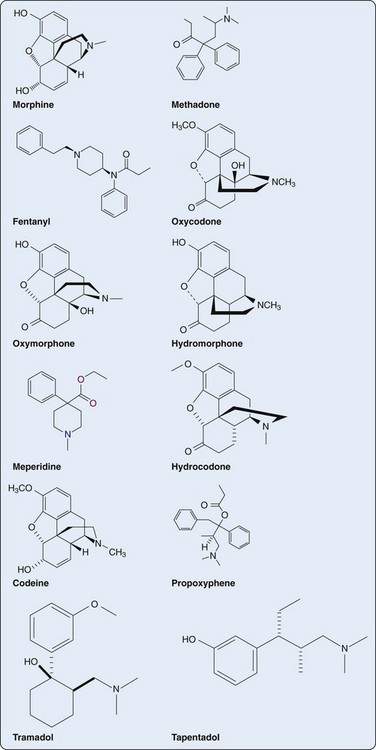

Morphine

Morphine is the gold standard against which all other opioids are measured. Morphine can be administered by oral, rectal, subcutaneous, intravenous, intramuscular, and intraspinal routes. Oral bioavailability of morphine is about 25% (range, 10% to 40%). Peak plasma concentrations occur 0.5 to 1 hour after ingestion with a half-life of around 3 to 4 hours. To increase the dosing interval of oral morphine, several sustained- and controlled-release preparations have been developed (Table 66-4). The average protein binding of morphine is around 35%, but this decreases with renal and hepatic dysfunction. Because of the hydrophilicity of morphine, there is poor central nervous system (CNS) penetration and little tissue accumulation with repeated dosing. Morphine is metabolized primarily in the liver to two main metabolites: morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G) and morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G). M3G is the primary metabolite with potent CNS excitatory properties. Because of its polarity, CNS penetration is poor; however, in renal failure, M3G plasma concentrations can be high enough to drive this metabolite into the CNS, leading to excitation. M6G possesses potent MOR agonism, but because of its high polarity, CNS penetration is poor. However, like M3G, M6G can accumulate in renal impairment, leading to exaggerated opioid effects. Only about 10% of unmetabolized morphine is excreted renally, whereas 90% is excreted renally as morphine glucuronide (70% to 80%) and normorphine (5% to 10%) conjugates.31

Table 66-4 Opioid Drug Interactions

From Daniell H: Inhibition of opioid analgesia by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, J Clin Oncol 20:2409, 2002; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: www.fda.gov/cder/drug/drugInteractions http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?cid=2284; http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=9154; http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=134337548&loc=es_rss; http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=134337351&loc=es_rss; http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=134338168&loc=es_rss; http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=134224843&loc=es_rss; http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=134223868&loc=es_rss; http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=126652570; http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=134338226&loc=es_rss; and http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=49969196&loc=es_rss.

Methadone

Because of the long half-life of methadone (average, 15 to 30 hours, with published reports ranging from 8 to 59 hours) with drug accumulation over several days, methadone needs to be administered with caution with long intervals between dose adjustments (5 to 7 days). Deaths have been reported with the use of methadone for chronic pain, and in November 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a public health advisory for methadone with a black box warning. Although details are often unclear, many of these deaths may be due to conversion of patients from other opioids to methadone. Methadone has been associated with QRS prolongation, which can lead to sudden cardiac death. If unfamiliar with the use of methadone, it is advisable to seek consultation with a pain specialist, especially when considering prescribing methadone at greater than a low dose (20 to 30 mg/day).32,33

The l-isomer of methadone possesses opioid activity, whereas the d-isomer is weak or inactive as an opioid. Evidence suggests that d-methadone is antinociceptive as a result of its N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist activity, making methadone attractive in treating neuropathic pain.34

Methadone is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, secondarily by CYP2D6, and to a smaller extent by CYP1A2 and additional enzymes that are under study. CYP3A4, the most abundant metabolic enzyme in the body, can vary 30-fold between individuals in terms of its presence and activity in the liver. In addition, drugs that inhibit this enzyme (several antiretrovirals, clarithromycin, itraconazole, ketoconazole, nefazadone, telithromycin, aprepitant, diltiazem, erythromycin, fluconazole, grapefruit juice, verapamil, cimetidine, and others) will increase the effect of methadone, possibly leading to overdose. This enzyme is also found in the gastrointestinal tract, so methadone metabolism actually starts before the drug enters the circulatory system. The amount of this enzyme in the intestine can vary up to 11-fold, partially accounting for the variable breakdown of methadone.35

Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a potent opioid with very high lipid solubility. This high lipid solubility leads to fast onset, a short duration of action, high protein binding (80%), and a high volume of distribution. The high volume of distribution accounts for the short duration of action owing to the high concentration gradient from the plasma to fat and muscle. However, with repeated dosing, the duration of action increases as fat and muscle stores become saturated with fentanyl. Although the analgesic half-life is around 1 to 2 hours, the terminal half-life is about 3 to 4 hours.36

Routes of delivery of fentanyl include transdermal, transmucosal, intravenous, and intraspinal. Subcutaneous delivery is also used in terminal cancer patients. High potency and lipid solubility make fentanyl ideal for transdermal and transmucosal delivery. Two transdermal fentanyl patches are available on the market: reservoir and matrix. The reservoir patch can be accessed and the fentanyl extracted, whereas the matrix patch is tamper-proof. Each system delivers fentanyl over 72 hours; however, some patients will deplete the patch within 48 hours, requiring more frequent patch changes. This variability can result from skin perspiration, fat stores, skin temperature, and muscle bulk. After application, the skin serves as a depot, and systemic levels rise for the next 12 to 24 hours, then remaining stable until 72 hours. Peak concentration occurs somewhere between 27 and 36 hours (25 mg 27 hours, 100 μg 36 hours). A steady state is reached after several applications. After removal of the system, plasma concentrations fall by 50% over 17 hours.37

Three transmucosal products are currently available. The fentanyl oralet contains fentanyl in a base of food starch, confectioners’ sugar (2 g vs. 30 g in a Snickers bar), edible glue, citric acid, and artificial berry flavor. The oralet is placed between the gum and the cheek and is allowed to dissolve over 15 minutes with bioavailability of about 50%. Onset is fast, with a peak effect at about 35 minutes. The fentanyl buccal tablets use an oravescent delivery system that generates a reaction that releases carbon dioxide when the tablet comes in contact with saliva. Transient pH changes accompanying the reaction optimize the dissolution (at a lower pH) of fentanyl through the buccal mucosa. Onset is fast with a peak effect at about 25 minutes. The Bio-Erodable Muco Adhesive (BEMA) fentanyl delivery system is composed of water-soluble polymeric films. This system consists of a bioadhesive layer bonded onto an inactive layer. The active ingredient, fentanyl citrate, is incorporated into the bioadhesive layer, which adheres to the moist buccal mucosa. The amount of fentanyl delivered transmucosally is proportional to the film surface area. It is believed that the inactive layer isolates the bioadhesive layer from the saliva, which may optimize delivery of fentanyl across the buccal mucosa, resulting in higher bioavailability (71%). Onset is fast with a slightly longer peak effect (60 minutes) as compared with the other transmucosal systems; however, there may be a longer duration. Chewing and swallowing any of the transmucosal fentanyl products results in lower bioavailability and peak effect because swallowed fentanyl is poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract.38

Fentanyl is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4 to the inactive metabolite norfentanyl; therefore, drugs that inhibit this enzyme will increase the drug effect (see earlier under “Methadone”). Only opioid-tolerant patients (>60 mg/day of oral morphine equivalent) should be started on fentanyl products owing to risks of severe respiratory depression.

Oxycodone and Oxymorphone

Oxycodone is administered by the oral or rectal route. Oral bioavailability is 60% and protein binding, 45%. Onset and duration of action are similar to morphine. Oxycodone is metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzyme primarily to noroxycodone, which has about 25% potency of the parent compound but also has neuroexcitatory effects. Minor metabolites include oxymorphone, which is more potent than oxycodone and has a longer half-life, and noroxymorphone, which has no analgesic properties.39

Oxymorphone is a metabolite of oxycodone and can be delivered via the oral and rectal routes. Both bioavailability and protein binding are low (10%), but terminal half-life is long (10 to 12 hours). Most of the oxymorphone is metabolized to oxymorphone-3-glucuronide, which is an inactive metabolite. Oxymorphone is available in immediate-release and sustained-release preparations.40

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone is administered by the oral, intravenous, intramuscular, and subcutaneous routes. Oral bioavailability is low (ranging from 25% to 50%), and protein binding is less than 20%. The kinetics are very similar to morphine. Hydromorphone has an extensive first-pass effect, and 95% is metabolized to the inactive hydromorphone-3-glucuronide. A 24-hour-release preparation of hydromorphone has been approved by the FDA. This preparation uses an osmotic piston-driven system in pill form that slowly delivers hydromorphone over 24 hours.41

Meperidine

Meperidine can be delivered by the oral, rectal, intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intraspinal routes. Meperidine use has decreased over time owing to side effects and risks associated with the parent compound and metabolites (see later). Oral bioavailability is about 50%, protein binding is about 60%, and peak concentrations in plasma usually are observed in 1 to 2 hours. Onset and duration are similar to morphine. Large doses of meperidine repeated at short intervals may produce an excitatory syndrome that includes hallucinations, tremors, muscle twitches, dilated pupils, hyperactive reflexes, and convulsions. These excitatory symptoms are caused by accumulation of the metabolite, normeperidine, which has a half-life of 15 to 20 hours compared with 3 hours for meperidine. Because normeperidine is eliminated by the kidney and the liver, decreased renal or hepatic function increases the likelihood of such toxicity. As a result of these properties, meperidine is not recommended for the treatment of chronic pain because of concerns over metabolite toxicity. It should not be used for longer than 48 hours or in doses greater than 600 mg/day.42,43

Codeine

The conversion of codeine to morphine is effected by CYP2D6. Well-characterized genetic polymorphisms in CYP2D6 lead to the inability to convert codeine to morphine, thus making codeine ineffective as an analgesic for about 10% of the white population. Other polymorphisms can lead to enhanced metabolism and thus to increased sensitivity to the effects of codeine.44 Variation in metabolic efficiency is evident among ethnic groups. For example, Chinese individuals produce less morphine from codeine than do whites and are less sensitive to the effects of morphine.45

Tramadol

Tramadol is 68% bioavailable after a single oral dose with about 20% protein binding. Its affinity for the opioid receptor is only  that of morphine. However, the primary O-demethylated metabolite of tramadol is two to four times as potent as the parent drug and may account for part of the analgesic effect. Tramadol is supplied as a racemic mixture, which is more effective than either enantiomer alone. The (+)-enantiomer binds to the receptor and inhibits serotonin uptake. The (−)-enantiomer inhibits norepinephrine uptake and stimulates α2-adrenergic receptors.46 The compound undergoes hepatic metabolism and renal excretion, with an elimination half-life of 6 hours for tramadol and 7.5 hours for its active metabolite. Analgesia begins within an hour of oral dosing and peaks within 2 to 3 hours. The duration of analgesia is about 6 hours. The maximum recommended daily dose is 400 mg. Tramadol is also available in an extended 24-hour release preparation.

that of morphine. However, the primary O-demethylated metabolite of tramadol is two to four times as potent as the parent drug and may account for part of the analgesic effect. Tramadol is supplied as a racemic mixture, which is more effective than either enantiomer alone. The (+)-enantiomer binds to the receptor and inhibits serotonin uptake. The (−)-enantiomer inhibits norepinephrine uptake and stimulates α2-adrenergic receptors.46 The compound undergoes hepatic metabolism and renal excretion, with an elimination half-life of 6 hours for tramadol and 7.5 hours for its active metabolite. Analgesia begins within an hour of oral dosing and peaks within 2 to 3 hours. The duration of analgesia is about 6 hours. The maximum recommended daily dose is 400 mg. Tramadol is also available in an extended 24-hour release preparation.

Physical dependence on and abuse of tramadol have been reported. Although its abuse potential is unclear, tramadol probably should be avoided in patients with a history of addiction. Because of its inhibitory effect on serotonin uptake, tramadol should not be used in patients taking MAO inhibitors and triptans. Seizures have been reported with concomitant use of selective serotonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and neuroleptics.46

Tapentadol

Similar to tramadol, tapentadol is contraindicated in patients taking MAO inhibitors, triptans, SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, and neuroleptics owing to risk of serotonin syndrome. There does not appear to be a risk of seizures, as is seen with tramadol. Tapentadol is currently available as an oral immediate-release drug; however, an extended-release preparation is in development (Figure 66-1).

Toxicity

Respiration

Although effects on respiration are readily demonstrated, clinically significant respiratory depression rarely occurs with standard analgesic doses in the absence of other contributing comorbidities or concomitant use of sedatives. In addition, the respiratory depressant effect of the opioid is significantly reduced with continued opioid use owing to tolerance. It should be stressed, however, that respiratory depression represents the primary cause of morbidity secondary to opiate therapy.47 In humans, death from opiate poisoning is nearly always due to respiratory arrest or obstruction.48 For example, In November of 2006, the FDA notified health care professionals of reports of death and life-threatening adverse events, such as respiratory depression and cardiac arrhythmias, in patients receiving methadone (FDA ALERT [11/2006]: Death, narcotic overdose, and serious cardiac arrhythmias, www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/methadone). Methadone appears to be involved in approximately one-third of all prescription opioid–related deaths, exceeding hydrocodone and oxycodone despite being prescribed one-tenth as often. This has led to revisions in methadone conversion tables.

At therapeutic doses, opiates depress all phases of respiration (rate, minute volume, and tidal exchange). High doses can produce irregular and agonal breathing.48 A number of factors can increase the risk of opioid-induced respiratory depression, even at therapeutic doses. These include (1) concomitant use of sedatives such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and tranquilizers, (2) obstructive and central sleep apnea, (3) extremes in age (both newborns and elderly), (4) comorbidities such as pulmonary disease and renal disease, and (5) removal of the painful stimulus. Pain serves as a respiratory stimulant, and removal of pain (e.g., neurolytic block with severe cancer pain) will reduce the ventilatory drive, leading to respiratory depression.

Sedation

Opiates can produce drowsiness and cognitive impairment, which can increase respiratory depression. These effects most typically are noted following initiation of opiate therapy or after a dose increase but usually resolve with continued opioid use. If the sedation does not resolve, other causes of the sedation should be investigated, such as concomitant use of other sedatives or the presence of sleep apnea. In the absence of these variables, opioid rotation may result in less sedation.49

Neuroendocrine Effect

Opioids inhibit the release of dopamine from neurons of the tuberoinfundibulum of the arcuate nucleus. Prolactin release from lactotrope cells in the anterior pituitary is under inhibitory control by dopamine; therefore the reduced dopamine caused by the opioids results in an increase in plasma prolactin. Prolactin counteracts the effects of dopamine, which is responsible for sexual arousal, and high levels of prolactin can result in impotence and loss of libido. Long-term opioid use can increase growth hormone by inhibiting somatostatin release; this regulates GH-releasing hormone secretion.50

Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and oxytocin are synthesized in the perikarya of the magnocellular neurons in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus and are released from the posterior pituitary. Kappa opioid receptor agonists inhibit the release of oxytocin and antidiuretic hormone (and cause prominent diuresis). MOR agonists have minimal effect or tend to produce antidiuretic effects in humans, and reduce oxytocin secretion.51 Some of the opioids (i.e., morphine) stimulate histamine release, resulting in hypotension and secondary ADH release. The effects of the opioids on vasopressin and oxytocin release may reflect both a direct effect upon terminal secretion and indirect effects upon dopaminergic and noradrenergic modulatory projections into the parventricular and supraoptic hypothalamus.52,53

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree