Fig. 23.1

Acromioclavicular joint injuries. Type I: AC sprain, few fibers torn. Type II: disruption of the acromioclavicular ligaments with coracoclavicular ligaments intact. Type III: disruption of the AC and coracoclavicular ligaments. Type IV: disruption of both ligament complexes with posterior clavicular displacement. Type V: disruption of both ligament complexes with marked superior clavicular displacement. Type VI: disruption of the ligament complexes with anterior entrapment beneath the coracoid

Table 23.1

Injury pattern of acromioclavicular joint according to the Rockwood classification

Type of injury | AC joint | AC ligament | CC ligament | Deltoid and trapezius muscles | Displacement of the clavicle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Type I | Intact | Sprain | Intact | Intact | Undisplaced |

Type II | Unstable in horizontal direction | Torn | Sprain/intact | Intact | Slight superior displacement |

Type III | Disrupted | Torn | Torn | Usually intact | Superior displacement |

Type IV | Disrupted | Torn | Torn | Detached | Posterior displacement |

Type V | Disrupted | Torn | Detached | Severe superior displacement with more than 100 % increase in the coracoclavicular space | |

Type VI (rare) Subcoracoid | Disrupted | Torn | Torn | Variable | Inferiorly |

Type VI (rare) Subacromial | Damaged partially or completely | Torn | Intact | Variable | Inferiorly |

23.2.3.1 Type I

Grossly type I injuries represent minor strains of the acromioclavicular ligament and joint capsule. Type I injuries are synonymous with grade I injuries. These injuries commonly result from direct force to the shoulder. The AC ligaments and the coracoclavicular ligaments are both intact although the AC ligaments are sprained. The deltotrapezial fascia is intact. Pain is minimal. The AC joint is stable and the radiographs at the time of injury are negative though periosteal calcification at the distal end of clavicle may be apparent later. The treatment is essentially conservative.

23.2.3.2 Type II

More significant forces cause type II or grade II injuries. In this type of injury the acromioclavicular ligaments are disrupted but the coracoclavicular ligaments are intact. However some degree of sprain of the CC ligament is present. The deltotrapezial fascia is also intact. AC joint instability is present especially in the anteroposterior plane. Vertical stability is present due to the intact coracoclavicular ligaments. Considerable pain and tenderness are present. The radiographs show slight elevation of the clavicle as compared to the acromion, even on stress x-rays. Due to some element of medial rotation of the scapula at the AC joint, there can be widening of the AC joint. The deformity and the instability become apparent on application of stress. These injuries are also managed conservatively with good results and only sparingly needing surgery.

23.2.3.3 Type III

This injury is characterized by rupture of both the acromioclavicular and the coracoclavicular ligaments. These are caused by forces which are strong enough to cause injury and disruption of both ligaments. Literature mostly says that the deltoid and trapezius muscles are intact and there is no significant disruption of the deltoid or trapezial fascia. Pain is severe on movements. The acromioclavicular joint is disrupted and the clavicle is displaced superiorly. There is gross instability of the acromioclavicular joint in both horizontal and anteroposterior planes. The stress views demonstrate that the distal clavicle is separated from the acromion and displaced superiorly. The radiographs show 25–100 % increase in the coracoclavicular space as compared to the normal side. The superior displacement of the clavicle is due to inferomedial drooping of the shoulder complex and the scapula. There are two schools of thoughts on the treatment of these injuries. Some surgeons advocate operative treatment but many orthopedicians give trial of a conservative treatment and go for surgery only when there are residual or persistent symptoms after 3–6 months. The physical status and the patient demands are also an important factor in deciding the treatment of these injuries. The author’s preferred treatment is also conservative initially with a close watch on the condition. In athletes also the same protocol is practiced by the author as the rehabilitation phase is very difficult in athletes after surgery.

23.2.3.4 Type IV

This injury is characterized by posterior displacement of the clavicle through the trapezius muscle. The force acting on the acromion drives the scapula anteriorly and inferiorly causing the posterior displacement of the clavicle. Both the acromioclavicular and the coracoclavicular ligaments are torn. The trapezial and the deltoid fascia are disrupted with the detachment of the deltoid and trapezius muscles. The clavicle may tent the posterior skin sometimes. The AP x-rays may be misleading as they may appear normal, although the axillary x-rays demonstrate the posterior displacement of the clavicle. CT scan is often required for delineation of these injuries. An important point to be noted with these injuries is that they are associated with the anterior displacement of the sternoclavicular joint. Thus in every case of type IV acromioclavicular injury, the sternoclavicular joint should be evaluated and imaging done. These injuries are relatively rare.

23.2.3.5 Type V

These injuries are severe forms of type III injuries when the deforming force is of a high amplitude. The acromioclavicular and the coracoclavicular ligaments are disrupted and the acromioclavicular joint is extremely unstable in both directions. The deltoid and the trapezius muscles are detached. The clavicle goes superiorly and the displacement is extreme. There is severe superior migration of the distal clavicle due to the unopposed action of the sternocleidomastoid along with drooping of the shoulder complex and scapula leading to marked disfigurement of the shoulder. The radiographic coracoclavicular distance is increased more than 100 % in comparison to the normal side. Some authors have suggested that there is a change in acromioclavicular distance of 100–300 % on radiographs [2] as compared to 25–100 % increase in the distal acromion-clavicle distance as seen in type III injury.

23.2.3.6 Type VI

These injuries are extremely rare. Gerber and Rockwood [15] have reported three cases and this series is the largest one reported in the literature. The injury is characterized by inferior dislocation of the clavicle. The injury represents severe trauma and is frequently associated with a number of other injuries. The injury is thought to be caused by hyperabduction and external rotation of the arm along with retraction of the scapula. The clavicle is inevitably found in either a subacromial or subcoracoid position. The ligament status and muscle injury depend on the displacement of the clavicle. In a subcoracoid position both the acromioclavicular and the coracoclavicular ligaments are disrupted and there is variable degree of damage to the deltoid and the trapezius muscles. The clavicle dislodges behind an intact conjoint tendon. In the subacromial position the acromioclavicular ligaments are torn but the coracoclavicular ligaments are intact. Most patients have associated paresthesia with the injury which resolved on relocation of the clavicle.

23.3 Clinical Presentation

The main symptom is pain and the main sign is tenderness located at the AC joint though swelling and deformity often accompany pain and tenderness. Any attempt to move the shoulder causes pain. The pain and tenderness increase with increase in the grade of dislocation. Abnormal protuberance of the distal end of the clavicle can be found with grade III or grade V acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Instability in the horizontal plane as well as the vertical plane can be assessed depending upon the grade of dislocations (described with the grades of dislocations) (Fig. 23.2).

Fig. 23.2

Clinical photograph of a patient with an acromioclavicular dislocation

23.4 Essential Radiology

23.4.1 The AP View and the Zanca’s View

The imaging of the acromioclavicular joint is slightly tricky. The x-rays taken for the shoulder usually have a high penetration for proper visualization of the glenohumeral structures. However the acromioclavicular joint gets overpenetrated in the process and is improperly visualized or seen more dark. In order to have a proper visualization of the AC joint, the penetration of the beam or the voltage is reduced by 50 % when compared to the x-ray being taken for the glenohumeral joint.

The other point of importance is that in a normal AP x-ray the distal clavicle and the acromion are superimposed by the spine of the scapula and proper visualization is not present. Zanca evaluated 1,000 x-rays of patients with shoulder pain and finally recommended the Zanca’s view in which the x-ray beam was given a 10–15° cephalic tilt to give an unobscured view of the acromioclavicular joint.

Also important is the comparison with the normal side to be certain not to miss the subtle changes indicative of an acromioclavicular injury. So it is recommended to take both the acromioclavicular joints imaged on the same film.

23.4.2 Lateral View/Axillary View

Only AP or Zanca’s views are not enough. Subtle anteroposterior displacements may be detected on lateral/axillary views. So it is always recommended to include the axillary views when imaging a case of suspected acromioclavicular dislocation. Also type IV injuries where the clavicle is displaced posteriorly may only be detected by the axillary views as the anteroposterior views may appear surprisingly normal.

23.4.3 Stress Views

With modern imaging and CT scans available, a lot of orthopedic surgeons do not prefer the stress views nowadays. The stress views have been conventionally used to differentiate between incomplete and complete AC joint disruptions (type II and type III injury). They are taken with a weight of 10–15 lbs (4.5–6.8 kg) that are suspended from both wrists of the patient and the AP x-rays of both sides AC joints taken and compared. In significant subluxations or dislocations, the lateral end of the clavicle is displaced superiorly. However the stress views cause significant discomfort to the patient and rarely provide any additional information. So they are rarely used nowadays.

23.4.4 Stryker Notch View

This view is taken with the patient supine and the hand of the patient is positioned on top of his/her head. X-ray beam is directed 10° cephalad centered on the coracoid process. This x-ray is able to give the best coracoid profile and identify all coracoid fractures which may be associated with AC joint dislocations. This image is to be taken in suspicion of a coracoid fracture when the AP projection shows an acromioclavicular dislocation but the coracoclavicular distance is normal [16] or comparable to the uninvolved opposite side.

23.4.5 CT Scan

A 3-dimensional CT scan is the preferred imaging technique for AC joint evaluation by the author. The 3D computed tomographic scan is very sensitive and specific in the detection of all acromioclavicular injuries, dislocations, and other pathologies. All displacements of the lateral end of the clavicle – superior, posterior, subcoracoid, subacromial, or inferior – can be easily delineated by a CT scan (Fig. 23.3).

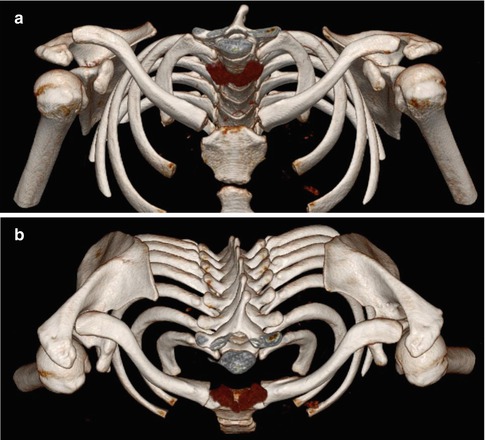

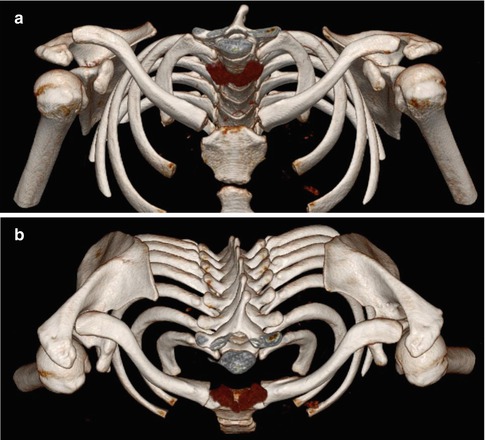

Fig. 23.3

(a) CT scan view with a 3-D image showing a right-sided acromioclavicular joint dislocation with superior migration of the clavicle. (b) CT scan top view with a 3-D image showing a right-sided acromioclavicular joint dislocation with posterior displacement of the clavicle on the right side

23.5 Treatment Options

The treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries varies according to the severity or grade of the injury and patient requirement.

The objective of treatment – operative or nonoperative – is to attain a pain-free shoulder with full range of motion, full power, and no limitation of activities. The demands differ from the general population to athletes and recreational athletes to professional athletes and these demands play an important role in deciding the management of the injury. However, there are few peer-reviewed studies of the treatment of AC joint injuries in athletes. No prospective studies compare the operative and nonoperative treatment in type III AC injuries in the group of patients. Thus there are no absolute indications for either type of treatment of this injury in athletes.

23.5.1 Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative treatment is almost always the rule for type I and type II injuries. General consensus is towards the conservative treatment of these injuries set aside special circumstances. For type I injury rest and immobilization in simple sling, strapping, or shoulder immobilizer for 1–2 weeks with ice application and pain management by NSAIDs lead to resolution of discomfort. For type II injuries this time is slightly longer and the immobilization is continued for 2–3 weeks with symptomatic and supportive treatment. Full return to activities is not started till the patient has resumed full range of painless motion. Sports activities can be resumed when all the symptoms have resolved and this is generally 6–8 weeks and this duration is even longer for type II injuries. Operative intervention is left for those who have persistent symptoms or unfavorable outcome with conservative treatment. However there has been increasing consciousness about the outcome of type I and type II injuries with conservative management. Moushine et al. [17] in their study had found out that 27 % of the conservatively managed type I and type II AC joint separations required further surgery at 26 months of injury. Also voices have been frequently raised regarding scapular dyskinesis arising as a sequelae to acromioclavicular joint dislocations [18]. With all the other facts taken into consideration, conservative management still remains the treatment of choice for type I and type II injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree