The assessment of these muscle imbalances of tight and weak muscles needs to be analyzed to ascertain if in fact the weak muscles are actually weak or just inhibited in their action. Research has demonstrated that certain groupings of tight muscles can directly affect the function of other muscles by neurologically inhibiting their ability to appropriately contract (Jull & Janda, 1987). The medical practitioner/coach may test this by stretching the tight muscles and then immediately retesting the strength of the weak muscles. If the weak muscles test strong, then there is an underlying neuromuscular inhibition of the weak muscle by the tight muscle.

Evaluation of how the upper and lower extremities affect the core needs to be performed. For example, does the gymnast experience increased back pain when performing trunk active range of motion with the arms raised up over head when compared to arms next to the side. This may indicate that a restriction involving the shoulder complex may be contributing to the back pain. This information is valuable in the construction of the rehabilitation program for the injured gymnast.

It is one thing to isolate specific muscles and test their function of strength and flexibility and it is another thing to functionally test these muscle groups. Just like an injured gymnast with a sprained ankle needs to regain the ability to balance on the injured extremity by performing static and dynamic proprioceptive drills, the gymnast with back pain needs to be able to restore proper static and dynamic proprioception and kinesthetic awareness. They need to be able to restore their ability to coordinate the function of the muscles to adequately control the spine with static positional holds and through dynamic core motions. The gymnast should able to “sense” and to “feel” that the appropriate muscles are working when performing the movement and know where their extremities are in positional relationship to their core. The gymnast may think they are positioning their core in proper alignment with their drill/skill. However, they may actually be in a piked or arched position in their core with a posterior or anterior tilted pelvis. The medical professional can have the gymnast perform specific clinical exercises to assess their body alignment awareness. In addition, the coach may have the gymnast perform some basic skills and analyze the gymnast’s body position with these movements too. There needs to be crossover from the medical clinic to the gym. Enhancement of the function of the gymnast’s skills with pain resolution is the ultimate goal.

Rapid growth during adolescence is another area to investigate when an adolescent gymnast presents with gradual onset of low back pain. With lengthening of the limbs and trunk, a loss of coordination and imbalance may occur. With this same lengthening a gymnast’s strength-to-length ratio may be altered and they become relatively weaker. The gymnast may also experience a relative tightness in muscles that were more flexible prior to the rapid change in growth. Female gymnasts experience a change in their pelvic shape during adolescence. This may alter their core dynamics.

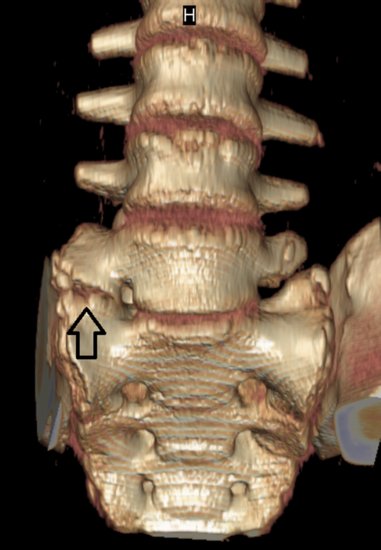

During adolescence, congenital issues of the spine may be brought to light. The gymnast may have a structural anomaly that was asymptomatic prior to the alteration in body size. This anomaly may then become symptomatic. With gradual onset of low back pain during adolescence, the medical professional should consider the possibility that the gymnast has a transitional lumbosacral vertebra, hemisacralization of the fifth lumbar vertebra, or partial lumbarization of the first sacral vertebra (Figure 13.1). These anomalies may create facet inflammation or sacralillitis due to the altered mechanics. Thoracic spine pain may be a result of the development of Scheuermann’s disease. Scoliosis may become more significant. The medical professional needs to be aware of these issues and include them in the differential diagnosis. Further discussion on these topics will occur elsewhere in this chapter.

Figure 13.1 3D CT scan showing a L5 vertebra with right-sided hemisacralization. (With courtesy of Lawrence Nassar.)

Rehabilitation of overuse injuries requires more than just rest. Rest is a relative term for a gymnast. In more significant and severe cases, complete rest from all gymnastics activity is required. However, in most mild to moderate cases, the gymnast requires relative rest. Relative rest is described as resting the gymnast from the aggravating skills and allowing him/her to continue participation in those skills that do not negatively influence the injury. The coach may be asked to participate in analyzing the skills that aggravate the gymnast’s spine to see if there is a flaw in the gymnast’s technique that needs to be addressed. The coach may assist in the recovery of the injured gymnast by breaking down the skill into its basic components and having the gymnast “relearn” the skill with improved form and technique. This may lend itself to less stress on the gymnast’s spine. These skills should not only include acrobatic skills but also dance skills.

The rehabilitation from a therapeutic exercise standpoint should be centered on the biomechanical evaluation of the gymnast. The tight muscle groups should first be addressed. Rehabilitation is different than conditioning. With conditioning, overstretching of a muscle at the start of a practice may negatively impact the power generating capacity of that muscle for up to an hour and coaches generally avoid this type of activity (Marek et al., 2005). However, with rehabilitation, the understanding of muscle inhibition needs to be first addressed. Therefore, it is important to start the rehabilitation session with muscle flexibility before the strengthening portion. By stretching the tight muscles first and then adding the strengthening drills, the gymnast’s muscle inhibition may be reduced and the inhibited muscle may respond better to the exercises. If this inhibition is not reversed, then the gymnast may actually reinforce the pathological pattern of muscle compensation. The use of foam rollers, massage sticks, and massage balls are beneficial for use to assist in the flexibility of muscles. The medical professional may perform myofascial release techniques: teach the gymnast special tri-plane myofascial unwinding exercises (Figure 13.2) and specific stretches to perform as part of a routine that initiates each rehabilitation session. Shoulder flexibility (Figure 13.3) and upper thoracic mobility assist with creating lower lumbar stability. The gymnast should be able to lift upwards through their arms pressing the upper thoracic spine caudad and anterior as they arch/extend their back creating a lengthening affect to the spine. They should be advised against shortening their spine by collapsing down and hinging at the lower lumbar spine.

Figure 13.2 Tri-plane myofascial unwinding of the lower extremity with hip flexion, hip adduction, and hip internal rotation combined with ankle inversion and ankle dorsiflexion. This can be done with a partner or with the use of a stretch cord. (With courtesy of Lawrence Nassar.)

Figure 13.3 Shoulder flexibility may be performed with the gymnast lying on a panel mat. The gymnast holds onto a light weight to assist with the stretch. They should keep their ribs flat, hips flat, and legs adductor together. The stretch should not cause them to arch their back and they should not allow their ribs to flare out. This helps to isolate the stretch to the shoulder complex. (With courtesy of Lawrence Nassar.)

During the flexibility phase of the rehabilitation session, the gymnast may benefit from slow deep breathing. It may be beneficial to have the gymnast hold the stretch for a certain number of deep slow breaths (i.e., 5–10 deep slow breaths) instead of having them focus on holding a stretch for a certain time period. They need to allow their bodies to relax to best respond to the flexibility activities. It may be important for the gymnast to perform short periods of stretching several times a day to improve their flexibility, that is, maybe 10–15 minutes of stretching per session, three to five sessions a day.

The strengthening of weak and inhibited muscles requires the gymnast to think. They need to be engaged mentally to ensure that the actual muscle/muscle groups are activating with the exercise. If the gymnast is distracted and not focused on the exercises, they may allow for further compensation to occur thus reinforcing the pathologic muscle patterning that created the back pain. If the gymnast is given a number of repetitions to do in a set, they should focus on proper technique with each repetition. If their form breaks down, they need to stop even if they have not completed the required number of repetitions. They need to build their strength with proper form first and then increase the number of repetitions. These types of details are important for a rehabilitation program to best accomplish its goals.

Strengthening exercises can be performed in a variety of ways. Static positional holds such as a side and prone planks are important to perform as part of the basic foundation of the rehabilitation program. Advancing to core exercises in which the gymnast is performing the exercises on a softer or wobbly surface may enhance the difficulty of the drills. The medical professional may incorporate the use of a Swiss ball, Bosu ball, wobble discs, and other such devices for this purpose. These devices may assist in not only strengthening the spine but also in enhancing the proprioception and kinesthetic awareness of the spine.

It is important to progress beyond static exercises. Dynamic exercises in which the spine is moved through a controlled range of motion, are beneficial to assist in the gymnast’s strength and kinesthetic awareness. The pelvic clock in which the gymnast learns to tilt their pelvis in a variety of directions using the face of a clock as a means to direct their motion is a basic dynamic core exercise. Side planks with arm and leg movements, twisting side planks, and rotational trunk motions while seated on a Swiss ball, are all examples of more advanced dynamic core exercises. In addition, core stability performed with the gymnast in a pike handstand and handstand position is beneficial to incorporate stability through the upper quadrant. For example, performing pike handstands on a wobble disc with the gymnast pressing through their shoulders to create clockwise and counterclockwise circles while maintaining a stable core position is a challenging core exercise (Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4 Piked handstand on a wobble disc. The gymnast presses through their shoulders to create clockwise and counterclockwise circles while maintaining a stable core position. (With courtesy of Lawrence Nassar.)

Manual medicine techniques for realignment of the spine and the extremities may be performed during the rehabilitation. These realignment techniques may allow the gymnast to improve the function and kinesthetic awareness of the spine. This may prove beneficial with assisting the gymnast’s recovery.

Therapeutic modalities involving a variety of means to heat and cool the injured tissue, augmented soft tissue mobilization techniques, acupuncture, vacuum cupping, laser light therapy, electrical stimulation, and therapeutic ultrasound are some of the commonly administered treatments as part of a comprehensive PT plan. The uses of rigid, semi-rigid, and soft elastic compression lumbar braces are frequently employed to alleviate more painful conditions. Adhesive strapping has been used for many decades; most recently Kinesio Taping techniques have been applied to the injured gymnast to assist with the treatment of spinal pain. The use of these therapeutic modalities requires further investigation since their evidence-based effectiveness has not been fully established.

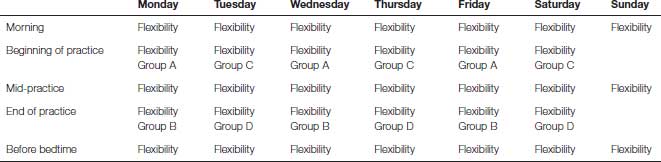

Rehabilitation programs may become overwhelming for a gymnast if they are told to do many exercises without a plan as to how to incorporate the exercises into their daily routine. The medical professional and coach should work together on implementing such a plan of action. First the number of strengthening exercises may be divided into four groups. If each group holds 3–4 core exercises, the gymnast is easily able to perform 12–16 different core exercises effectively in a week without overwhelming the gymnast by doing too many at one time. Each group can have a balance between static and dynamic exercises, incorporate a good variety of exercises so as not to overemphasize one motion pattern in a single group, and avoid quickly fatiguing a specific muscle group. This helps to prevent the gymnast from going into a pathological compensatory muscle firing pattern while performing their rehabilitation exercises. The gymnast may perform one of the exercise groups at the beginning of each practice and one of the exercise groups at the end of each practice on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Repeat this template with the other two exercise groups for Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. In addition, the flexibility/mobility of the restricted muscles and body regions needs to be incorporated into the schedule as well. Finding time to stretch/foam roll three to five times a day may be a difficult task if it is not planned out in advance for the gymnast. Please see Table 13.2 below for an overview of a weekly plan for a spinal rehabilitation program.

Table 13.2 Chart overview of a weekly spinal rehabilitation program. Flexibility refers to the use of stretches, foam roller, myo stick, myo ball, and so on, to enhance motion of a restricted/tight muscle or body region. Group A, Group B, Group C, and Group D refer to the four different exercise groups to enhance core strength and core proprioception/kinesthetic awareness.

Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis

Stress fractures to the spine most commonly occur in the lower lumbar posterior column. Spondylolysis is the term used for these types of fractures. Spondylolysis is defined as a fatigue fracture of the vertebral arch usually occurring at the pars interarticularis. Spondylolysis may also occur through the pedicle portion of the posterior vertebra, but this is far rarer. This is a stress overuse injury that is created by repetitive hyperextension and rotation of the spine (Standaert & Herring, 2000). An acute traumatic event creating a microfracturing of the bone may be an initial insult. The fracture is then completed by the repetition of extension and rotation forces. The fifth and fourth lumbar vertebrae are the most common location of these fractures. Spondylolysis that occurs above L4 may take longer to heal then those that are at L4 or L5. Unilateral spondylolysis, either on the right side or left side of the vertebra (Figure 13.5), has an easier course of recovery, in general, than a bilateral spondylolysis in which both sides are damaged.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>