The foot has a “complex” anatomy with several bones adjacent to each other, thus projecting over each other on plain radiographs and complicating the decision of a correct diagnosis in the acute phase. Aggravated, prolonged, or recurrent symptoms when increasing the gymnastics program need further investigation.

General treatment and rehabilitation for lower extremity injuries

The treatment strategy for the following (acute) lower extremity injuries is roughly according to the subsequent general protocol. It should be noticed, that there is lack of literature about rehabilitation programs and techniques for lower extremity injuries in gymnastics. The protocol includes recommendations from experience and is based on the guideline and general principles of Sports Medicine (see also “Recommended reading”), and has to be individualized and specified for the different gymnastics disciplines.

Acute phase

The RICE therapy for the first 3–5 days after the acute trauma may be prescribed for the relief in the acute period (reduction of swelling and pain) (Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 RICE therapy in the acute phase after trauma.

| RICE | Description of the therapy |

| Rest | Is recommended during the inflammatory response to the tissue damage. Controlled active dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the ankle, or extension and flexion of the knee if possible and weight bearing are allowed within the pain threshold, otherwise shortly non-weight bearing with crutches. |

| Ice application | Is not proven to reduce the swelling. But intermittently application can be considered to reduce the localized pain in the short-term. |

| Compression | By using elastic bandage, it may have a positive effect on the decrease of swelling and pain. The relationship between a faster decrease of swelling by compression and ultimately a faster functional recovery is not proven. |

| Elevation | Is the most effective strategy in reducing the swelling in the short-term. |

Anti-inflammatory medication is prescribed for acute pain management and because of the possible side effects, the first choice is regular painkiller such as Panadol.

Electrotherapy, lasertherapy, and ultrasound therapy have no added value to the acute treatment.

Connective tissue massage and lymph drainage techniques are increasingly applied for reducing the swelling, but have not yet been studied in controlled trials.

During the treatment period isometric muscle strengthening can be started to prevent significant atrophy.

Recovery and rehabilitation phase

In the early recovery phase, joint mobilization and defined exercises, which can be applied at home, are important to stimulate the vascularization and neural system and to avoid joint stiffness.

Rehabilitation always consists of a well-monitored program with progressive exercises for strength (functionally or with weights), first in closed kinetic chain and later in open kinetic chain, of the pelvic/gluteal muscles, quadriceps (especially the vastus medialis) and hamstrings, and calf and foot muscles. Exercises for core stability and neuromuscular training can be started initially in the supine position.

Conditioning exercises, controlled and technical jump and landings exercises, and agility training will be finally added.

Continuing the exercise program for muscle strength and flexibility of the upper extremity, the upper body, and the back, as well as core stability regimen is a must to prevent another new injury and help ensure a faster return to gymnastics.

Treatment of any treatable predisposing factors is important to prevent recurrence or new injury.

Sports-specific phase

Proprioception and balance exercises of the injured joint must be completed before returning to basic gymnastics. Single-leg “hoptests” (particularly the “triple hoptest”), such as vertical (up–down), horizontal (forward), sideways, and “figure-of-8” hoptests are good indicators for functional recovery.

Leg activities should always be resumed on a soft surface, with (extra) mats, or on trampoline (possibly supported with spotting belt) and later on the tumbling track. Twist and “compound” landings and hard landings have to be avoided until the rehabilitation program is finished.

Finally, the gymnast can return slowly to full training when the clinical symptoms are completely resolved. Pain will be the main guideline, which can be monitored by the “visual analog scale” (VAS) score, evaluated by the gymnast ranging from 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (the most severe pain ever).

Protection by using a brace or tape for the injured ligaments during rehabilitation and when resuming (basic) gymnastics training is advisable. The preferred type of brace for the ankle is the soft brace, such as a lace-up brace or a semi-rigid brace.

To maintain the “feeling” with the apparatus during the rehabilitation phase, the gymnast is encouraged to do basic skills, without dismounts, on the “hanging” apparatus such as uneven and high bar and rings or on the “arm supportive” apparatus such as pommel horse and parallel bar.

Furthermore, this is important for female gymnasts, who do not use a dowel grip on the uneven bars, to avoid reduction of hand palm callosity.

Full muscle strength, full end range of motion, coordination, balance, and symmetric core stability should be restored before resuming competition.

Dislocation of joints

Patella

The mechanism for patellar dislocation is usually either a direct blow on the femur condyles or on the (medial) patella in a fall or a twisting injury in which the femur is internally rotated upon the fixed tibia in the flexed knee, for example, during a “stick” landing with the affected leg out of balance. This trauma mechanism is similar to that for an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, which may occur in association with this injury.

Another mechanism is a sudden burst of quadriceps activity in the landings, for example, when stepping behind with the affected leg extended for a “stick” landing (with “spread legs”).

Patellar dislocation is highly predisposed in the hypermobile patellofemoral joint (in association with patella alta (“high-riding patella”) and/or patellofemoral dysplasia) and is at high risk in gymnastics due to the multiple rotational landings. Muscular weakness or imbalance can be associated with, but may also be the result of, patellar dislocations. The patella dislocates laterally out of its groove onto the lateral femoral condyle and acutely spontaneous reposition often occurs, with knee extension.

An acute dislocation of the patella may be accompanied by different lesions such as a tear of the medial retinaculum and vastus medialis expansion; and avulsion fracture, osteochondral fracture or bone bruise/contusion of the medial patellar margin and/or lateral femoral epicondyle/trochlea; and chondral fractures of the patellar joint surface (“flakes”).

After the primary (first-time) patellar dislocation, residual laxity of a medial retinacular injury may produce patellar instability, and this in turn may produce recurrent anterior pain and symptomatic giving-way. The anterior knee pain should be differentiated from patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Treatment of acute dislocation is repositioning of the patella, after painkiller administration or regional anesthesia, by extending the knee and putting local pressure on the patella in the medial direction.

After reduction, the initial treatment plan in cases without associated lesions is conservative with a splint in knee extension and pain management. After a week, a limited motion knee brace in 30° flexion of the knee can be prescribed, with gradually increasing knee flexion during 6 weeks, for example, with 15° every week to 45°, 60°, 75°, 90° flexion, respectively (Figure 12.2).

Figure 12.2 Limited motion knee braces: (A) in front view (B) in side view, with detailed hinge in degrees.

Isometric muscle strengthening can be started to prevent significant atrophy. After 6 weeks treatment, protection with a brace may be continued until full knee flexion takes place. This schedule should be individually based, dependent on the severity of pain and swelling and may be shortened or prolonged. Well-developed vastus medialis (obliquus) muscle is essential for good patellar tracking.

Arthroscopy is required in cases of osteochondral fracture or flakes of the patellar joint surface, with operative repair in cases of the medial retinaculum rupture.

The primary treatment of chronic patellar instability is the same as after the acute (first) dislocation.

But when previous symptoms and anatomic disorders are present, conservative treatment generally has a poor outcome.

Foot

The loads during landings are most essential at the tibiotalar joint and talonavicular joint (Chilvers et al., 2007). As these loads are high-energetic, dislocations of the foot in gymnastics can occur in the whole foot in association with fractures, like in the tarsometarsal joints (TMT or Lisfranc’s joint), the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints (Chopart’s joint), and even in the naviculocuneiform joint (See Figure 12.1C).

Dislocation of tendons

Peroneal tendon

Dislocation of the peroneal tendon can occur in forced passive ankle dorsiflexion like in deep forward landings in gymnastics or in inversion ankle trauma with subsequent forceful contraction of the peroneus to prevent this motion. The dislocation can persist in ankle eversion and plantar flexion activities, causing recurrent ankle sprains or giving-way feeling and tenosynovitis, and this condition requires surgical treatment.

Sprains

Knee sprains

Medial collateral ligament

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) in gymnastics may be injured frequently with other intraarticular knee injuries, such as an ACL rupture and (medial) meniscal tear known as the “unhappy triad.” The prognosis will depend on the most severe concomitant injury.

The injury mechanism is a (in)direct valgus stress trauma of the knee with the foot planted and slightly external rotated and the knee being forced inward, like in an off-balance landing in gymnastics. The severity of the ligament tear can be classified into grade I (mild), grade II (moderate), or grade III (complete rupture).

The treatment can be conservative for all grades with a knee brace. The more severe injuries (grade II and III) require a longer rehabilitation (about twice as long) than the mild (grade I) injuries before returning to full sports activity.

Anterior cruciate ligament

ACL ruptures in gymnastics may occur in landings with flexed (as well as extended) knees from the rotational acrobatics movements, especially in dismounts, including during the vault. A “popping sound” may be heard and usually there is swelling within few hours.

Females are more prone to ACL injuries because of the smaller ACL size and smaller intercondylar notch of the femur (Hutchinson & Ireland, 1995).

On examination, the Lachman’s test and anterior drawer sign are positive and a positive Pivot shift is pathognomic for the ACL rupture. In the acute phase this is difficult to perform, since the patient cannot relax sufficiently due to the pain and swelling. The tests should be performed either in the very acute phase (within 1 hour) or in the delayed phase after 5–7 days.

History and clinical findings are most important and MRI can confirm the diagnosis and show concomitant intraarticular lesions.

Gymnastics is a “cruciate-dependent” sport. A rupture of the ACL with a positive pivot shift sign is therefore not compatible with gymnastics at elite level because of the high-demanding rotational acrobatic skills. Surgical reconstruction is then required, particularly when concomitant lesions are present.

In a skeletally immature patient, surgical treatment of an ACL rupture poses additional challenges. There are several surgical reconstructions and the goal is to recreate ACL stability without causing growth plate arrest, with leg-length discrepancy or angular deformity. The approximate degree of skeletal maturity determines the timing. Arthroscopically performed reconstruction is recommended and the choice for the graft depends on the surgeon’s (and patient’s) preference and experience and can be an autologous graft (the own body’s tendon, with preference for hamstrings tendon in gymnasts) or allograft (cadaver’s graft of a tendon). Autologous reconstruction with patellar tendon can cause patellar tendinopathy in sports with explosive and repetitive jumping activities, such as gymnastics.

A delayed reconstruction of 4–6 weeks after the injury will give better outcome as the risk for arthrofibrosis and “cyclops” formation (connective tissue mass/scar tissue nearby the entrance of the graft at the tibial plateau) is lower and the graft will better develop in a favourable intraarticular environment of the knee with slight or no swelling and a nearly normal range of motion and gait.

An intense medical and physiotherapy program should commence following the acute trauma (see Section “General treatment and rehabilitation for lower extremity injuries”) for an optimal preoperative preparation.

Specifically in gymnastics, because of the nature of the sport, the rehabilitation time takes approximately 9–12 months prior to return to full gymnastics on competition level and rehabilitation management must be very well defined in time frames with written protocols. Teamwork with realistic goals is required during this period.

Initially, neuromuscular electrostimulation can be used for supporting the (muscle) exercises. And wearing a protective knee brace with hinges (e.g., CTI or Don Joy brace) is recommended, particularly in the first 6 weeks for safety.

Caution must be advised for the ingrowth of the graft tissue. In gymnasts with increased ligamentous laxity, full extension drills and mobilization techniques should be restricted.

After 6 months of post-operative period, rapid progression to functional and strength exercises specific for gymnastics can take place. Agility tests, functional tests, and isokinetic Cybex/Biodex testing can be used to evaluate the level of progression and the differences with the uninjured leg, aiming for the quadriceps strength of at least 90% of the uninjured leg and the hamstrings strength at 100%.

However, the rehabilitation schedule should be individually programmed, dependent on the function of the knee, and should be adapted based on the monitored individual symptoms and signs of the knee during and after the exercises, only allowing progress to the next step when the actual program can be performed without pain and swelling.

In reconstructions with hamstrings autologous graft, loss of full knee flexion or sometimes of full hamstrings strength may occur. A rehabilitation program similar for hamstrings muscle tear is useful.

Posterior cruciate ligament

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) rupture occurs more frequently in direct forced posterior trauma on the proximal tibia with the knee flexed, but in gymnastics it occurs in landings (especially on the vault apparatus) with hyperextended knees. Hyperextension trauma occurs when the gymnast does not yet expect to land, but the feet strike the ground before the leg muscles can actively absorb the landing forces on the knee.

Treatment for an isolated PCL rupture is conservative with non-weight-bearing immobilization in a brace or splint in the acute phase (for 1 week), followed by use of a knee brace for 6 weeks. Intensive strength training with stability and proprioception training show good results and returning to gymnastics to the pre-injury level is possible, despite the persisting laxity.

Surgery is indicated in the combined tears with posterolateral rotatory instability.

Meniscus

In gymnastics, acute medial as well as lateral meniscus tears can occur from rotational landings and from landings with hyperextended knees. In children and adolescents, a discoid meniscus and meniscal cyst, most frequently located on the lateral side of the knee, can mimic meniscal tear symptoms.

The treatment depends on the associated ligament tears or cartilage damage. The goal is to maintain as much of the meniscus as possible for its load absorption properties.

Minimal and stable meniscal tears (without displacement) can be treated conservatively. Persistent swelling, pain, and symptomatic locking symptoms of the knee will need arthroscopy.

Post-surgery rehabilitation will take 6 weeks, but this will not always mean full gymnastics activity or competition at the end of the 6 weeks. The rehabilitation program can take longer in cases of complicated tears or in lateral meniscal tears.

Ankle sprains

Lateral ankle ligament injuries

Ankle sprains are the most common sports injury with the anterior lateral ankle ligament being mostly injured.

The main intrinsic predisposing factors for the lateral ankle ligament injuries are the muscle strength of the lower leg, proprioception and balance characteristics, and range of motion of the ankle. Limited ankle dorsal flexion and reduced propriopception are indicative of an increased risk of sustaining lateral ankle ligament injuries, and previous ankle sprain in the past is a plausible risk factor (Kerkhoffs et al., 2012).

Extrinsic predisposing factors are for example the type of the performed sport and whether a competition is involved. Dismounts in gymnastics are always performed at the end of (complex) routines and may increase the risk of injury, as the gymnast might be fatigued with diminished levels of coordination and strength.

The diagnosis of the lateral ligament rupture after an acute ankle sprain can be made with a high degree of reliability by delayed physical examination 4–5 days after the acute trauma based on the presence of hematoma, accompanied by local pressure pain or a positive anterior drawer test or both (van Dijk et al., 1996), together with an accurate history relating to the trauma mechanism.

Functional treatment of acute ankle ligament injury is still the “gold standard” and preferred over surgical therapy.

After an acute lateral ligament injury, there is a delayed reaction time of the peroneus muscles due to the (traction) injury of the peroneal nerve and decrease of the strength of the extensor and evertor muscles, and other muscle groups around the ankle.

So the treatment management should consist of various exercises, all within the pain limits, ranging from proprioceptive training by using a wobble board as well as training on one leg with closed eyes (to turn off the optical control), muscle strength, muscle coordination, and joint mobility exercises of the whole limb. In the rehabilitation phase, the damaged ligament(s) must be protected by external support, either by tape or brace.

In an ankle sprain without rupture of the lateral ligament, the rehabilitation program is the same, but shorter in duration.

Surgical repair of ankle ligament injuries can be considered for professional and elite athletes, but on an individual basis. Even after surgery, however, it is necessary to take sufficient time for wound healing and for the rehabilitation program before returning to competitive gymnastics. So the decision to opt for surgery or for functional treatment also depends on the time of the gymnastics season and the history of chronic instability, time from trauma to diagnosis, associated ankle joint damage, and access to an experienced foot/ankle surgeon (Kerkhoffs & Tol, 2012).

Exercise therapy with proprioception, coordination and balance training, and home exercises are mostly considered as the strategy for the secondary prevention, even for longer period, up to 12 months after the first ankle ligament injury. Wearing either a brace or tape during gymnastics landing skills is useful in the prevention after a lateral ankle ligament injury. A lace-up or semi-rigid brace may be preferable to tape in the preventive strategy since for the long-term use it is better for the skin and in terms of the evaluation of cost.

Complete recovery is essential, otherwise there will be decreased performance for a prolonged time and an increased risk for a new or recurrent injury.

Medial ankle ligament injuries (“deltoid ligament”)

In gymnastics, deltoid ligament rupture can occur frequently in the hyperdorsiflexion trauma mechanism with overpronation as seen in deep acrobatic landings, following initial landings on the forefoot. A rupture of the deltoid ligament can be accompanied by a (longitudinal) rupture of the tibialis posterior or the flexor hallucis longus tendon.

Rehabilitation for the deltoid ligament injury is the same as for the lateral ligament injury, but it takes twice as long before returning to full gymnastics, especially in case of calcifications in the injured deltoid ligament or a concomitant bony or chondral lesion, sometimes requiring arthroscopy.

General attention in ankle sprains

Due to the often great height of dismounts from the apparatus and incomplete rotation in the landing (increasing the impact of the landing), extreme compression in the ankle joint may lead to more severe injuries, which are not recognized at the time of the initial (clinical) presentation.

Any sprain that does not improve with adequate treatment should always be reconsidered. The possible associated injuries are: osteochondral lesions or stress fractures of the talar dome, tibial plafond, lateral talar process, posterior process of the talus (e.g., Cedell fracture, a fracture of the medial tubercle of the posterior process, however rare), and anterior calcaneal process.

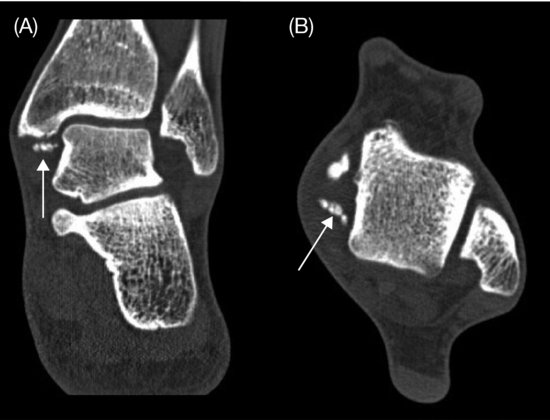

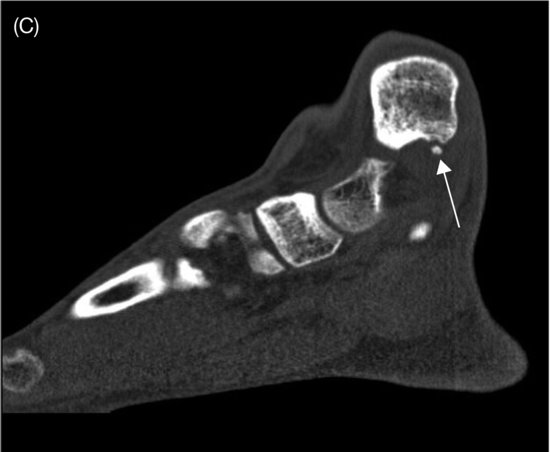

Ankle impingement syndrome

Anterior soft tissue ankle impingement may develop after a ligament rupture with interposition of the torn parts of the ligament. In the bony impingement, the repetitive microtraumas in the ankle induce spur formation, such as osteophytes or ossicles, which in turn provoke the process of synovial impingement (Figure 12.3). It is not the osteophyte itself that is painful, but the compression of the inflamed soft tissue caught between the traction spurs and the osteophytes (van Dijk, 2006).

Figure 12.3 (Posterior) medial fragments in the ankle, causing impingement. CT scan of the ankle: (A) coronal (arrow), (B) axial (arrow), and (C) sagittal (arrow) view.