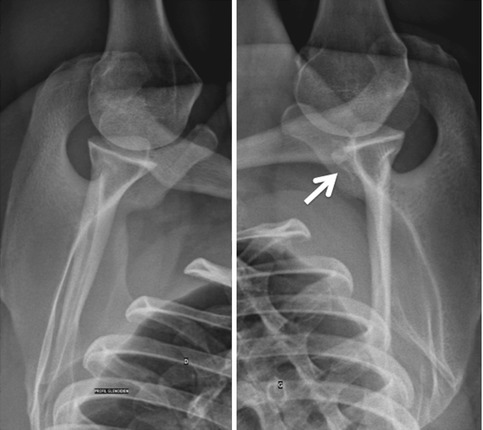

Fig. 18.1

This figure shows a large bony Bankart lesion (white arrows) in an AP standard X-ray

Fig. 18.2

This figure shows an AC joint-centered X-ray of the same patient as in Fig. 18.1. The large bony Bankart lesion can be seen (white arrows)

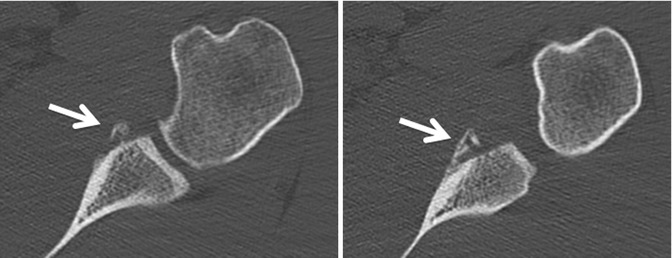

Fig. 18.3

This figure depicts the so-called Bernageau axillary view depicting adequately the anterior and posterior parts of the glenoid. The white arrow marks the medialized large bony Bankart lesion (same patient as Figs. 18.1 and 18.2). In case of resorption, the glenoid osseous defect can already be estimated

A significant advancement in the care of patients with shoulder instability would be the ability to categorize the patients with first-time dislocations to an initial treatment plan with the most beneficial outcome. MRI could be a useful imaging modality to find lesions after shoulder dislocation. In a study by [35], 58 patients with traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation were treated with closed reduction and were examined by MRI after 2 weeks. The hemarthrosis or effusion present in the joint after the primary dislocation was used as a contrast for arthrography to identify the lesions present on MRI. At follow-up more than 8 years later, the MRI findings were compared to the shoulder function, shoulder stability, Rowe score, and Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Besides the age of the patient being above 30, the MRI findings analyzed showed that a bony Bankart lesion is a good prognostic factor for a good functional result and a stable shoulder after a primary dislocation. The glenoid rim fracture was only detected on plain radiographs in 60 % of those found on MRI [35].

For this reason, the authors are working on a study creating a threshold of anterior translation in a loaded open-MRI condition for patients after shoulder dislocation. Briefly, the humerus is pulled anteriorly with 20 N and the arm weight neutralized by a lever-arm system. On a 3D reconstruction of the open-MRI acquisitions, glenohumeral translations are calculated. The system was validated on healthy subjects and now patients with status post shoulder dislocation are being analyzed.

Accurately measuring the size of the osseous defect requires advanced imaging modalities. Although computed tomography (CT) is generally thought to be more accurate to estimate bony fragments (Fig. 18.4), a recent study on 18 cadaveric glenoids showed a similar accuracy of MRI when compared to CT and 3D CT, using the circle method [11]. However, the drawback of this study was that the cadaveric glenoids were not surrounded by soft tissues, which makes the distinction between bone and labral-capsular complex difficult. One study correlated glenoid bone loss seen on a 3D en face view to arthroscopic findings. Arthroscopic findings were assessed with a probe measuring the anterior-posterior width at the level of the bare spot. The authors found a high sensitivity of 92.7 % and specificity of 77.8 %. Currently the “circle method” in a 3D CT seems to remain the gold standard for the estimation of glenoid bone loss preoperatively [37]. The circle method establishes a percentage out of two areas. It uses the area (area 1) of a circle around the glenoid touching the superior and inferior glenoid rim. The area of the fragment (area 2) is estimated with a freehand measurement tool. The percentage bone loss is the ratio between area 2 and area 1. Yet, this method does not account for the location of the fragment.

Fig. 18.4

This figure shows a medium-sized (>5 mm) bony Bankart lesion that is medialized. Note the difference in lesion size between the two CT slices. This lesion already demonstrates medialized bony healing and thus does not qualify for a simple Bankart repair. Additionally, the estimated glenoid bone loss represents more than 25 % of glenoid width. The arrows point to the medialized bony Bankart lesion

A possible Hill-Sachs lesion should be ruled out, and if present, the glenoid track should be estimated according to Yamamoto et al. to control if the Hill-Sachs lesion might be too medial and thus engage [42]. The glenoid track is defined as 84 % of the glenoid width implying the importance of the glenoid bone loss decreasing the glenoid width.

The authors’ preferred method is the estimation of anterior glenoid bone loss on the en face view in a 3D CT scan, which is obtained for all patients preoperatively. Nevertheless, the authors would like to emphasize that bony fragments are usually underestimated even in a 3D scan, and this should be taken into consideration in decision making.

When reviewing imaging, a CT may be useful for assessing the bony lesion and labrum but not so helpful when it comes to looking at the ligamentous tissue, for which an MRI is more appropriate. Decision making depends upon information being available about the status of the ligamentous tissue as well as the bony defect. It may be that only on arthroscopic examination of the shoulder does the surgeon become aware of significant ligamentous injury necessitating a bony reconstruction.

18.5 Disease-Specific Clinical and Arthroscopic Pathology

Firstly, a comprehensive and specific history of the patient should be noted. Demographic parameters such as age, gender, job, type of sport (contact vs. non-contact), and level of sport (competitive vs. recreational) should be recorded. Next, the details of the dislocations should be taken including how many shoulder dislocations have taken place, direction of the shoulder dislocation, who reduced the shoulder joint (patient, physician, physician in operating room), and previous shoulder operations.

The above-stated factors are important in determining the needs of the patient and the severity of the injury (reduction in the operating room suggests a severe injury with Hill-Sachs lesion and glenoid bone loss).

Clinically, range of motion is tested including internal and external rotation at 90° of humeral abduction (IR2 and ER2, respectively). Most patients will complain of apprehension at ER2, which should be noted besides the measured angles. Apprehension should not only be tested at 90° but also at 0° and 140° of humeral abduction. The Gagey test gives an estimate of inferior glenohumeral ligament laxity [8]. Rotator cuff integrity is tested with the Jobe (supraspinatus), the palm-up (infraspinatus), and the belly-press (subscapularis) test.

Once the indication for an operative treatment has been made, arthroscopy is performed in a beach chair position. Regarding the indications, please see below.

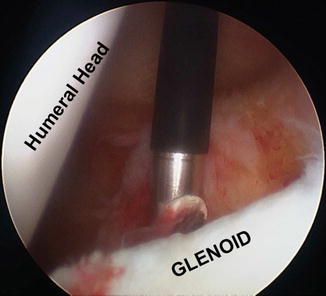

Two portals are used to assess glenoid bone loss: the posterior portal for the camera (Figs. 18.5 and 18.6) and the rotator interval portal for instrumentation. Firstly, a diagnostic arthroscopy is performed for concomitant pathologies, such as labral detachment, SLAP, biceps, rotator cuff, Hill-Sachs, HAGL (humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament), and posterior labral lesions. The glenoid is now viewed with the best “en face” view possible. The anterior sleeve is checked for a possible ALPSA (anterior labral periosteal sleeve avulsion) lesion [25, 26]. The presence of an “inverted pear” is noted suggesting a glenoid width loss of at least 25–27 % [20]. A probe is inserted in the rotator interval portal and the percentage of glenoid osseous is measured at the height of the bare spot as proposed by Burkart et al. [4]. For better estimation of the lesion, the camera is inserted into the rotator interval portal (Fig. 18.7) using a switching stick.

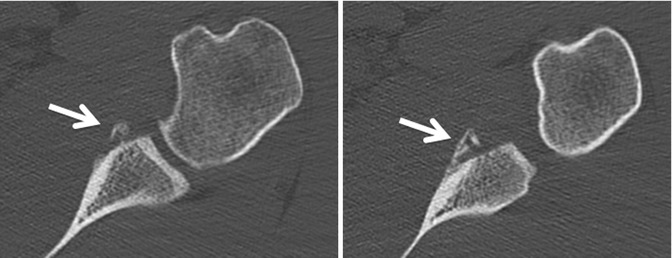

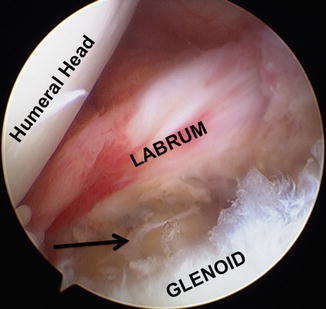

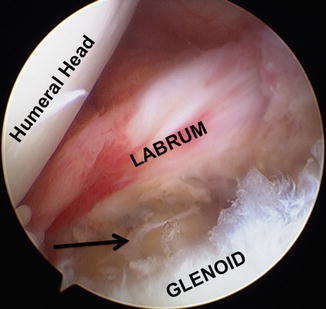

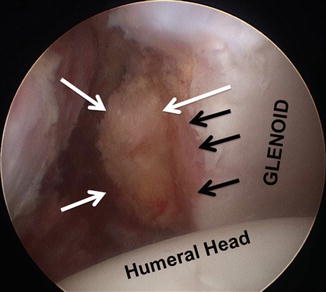

Fig. 18.5

Posterior view on the anterior glenoid. The lesion seems misleading and a soft tissue repair might be performed (same patient as in the Figures showing the CTs)

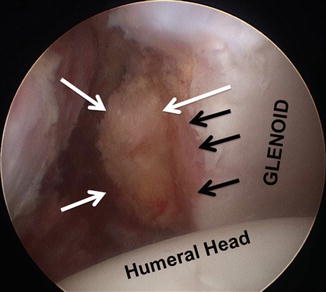

Fig. 18.6

Similar situation as in Fig. 18.5 with a posterior view. The big bony Bankart (same patient as in X-rays) is marked with a black arrow. The size can easily be underestimated intraoperatively

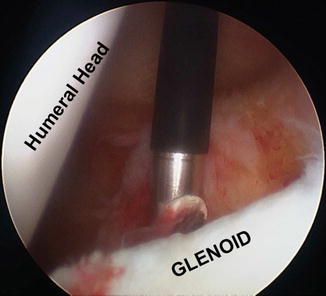

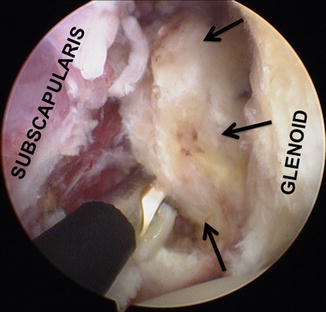

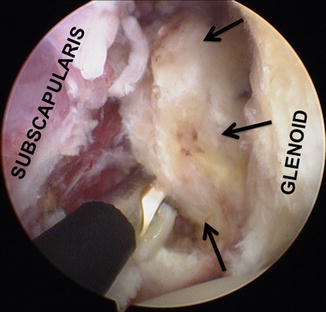

Fig. 18.7

The rotator interval view and the debridement reveals the medialized healed bony Bankart lesion (white arrows). This is the same patient as in the figures showing the CTs. The black arrows show the glenoid osseous defect

18.6 Treatment Options

Treatment algorithms have traditionally included a period of nonoperative management in all patients; however, young athletic patients may often benefit from early operative treatment [7].

The indication for an operative approach should be based on multiple factors arising from the history of the patient, the clinical examination, the radiographic evaluation, and the arthroscopic findings.

18.6.1 Nonoperative Treatment

After a thorough history, clinical examination, and appropriate imaging (3D CT) indicating a small bony fragment in an anatomical position, nonoperative treatment can be tried with the arm in an internally rotated position in a sling. A recent meta-analysis has shown no benefit of the arm in external rotation [40]. In the majority of the cases, in the presence of a bony fragment, operative treatment is the treatment of choice after a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation.

18.6.2 Operative Treatment

Both open and arthroscopic surgical approaches have been well described, with recent studies of arthroscopic soft tissue techniques reporting results equal to those of the more traditional open techniques [5].

The double-row suture technique is a new concept for arthroscopic treatment of bony Bankart lesion in shoulder instability. It presents a new and reproducible technique for arthroscopic fixation of bony Bankart fragments with suture anchors. This technique creates double-mattress sutures, which compress the fragment against its bone bed and restores better bony anatomy of the anterior glenoid rim with stable and non-tilting fixation that may improve healing [45]. Lafosse et al. described the Cassiopeia technique for creating such a double row with suture anchors [16]. This technique creates a W-shaped configuration with a strong tissue grip as the main advantage.

Although small bony lesions may be relatively rare compared with soft tissue pathology, they constitute a critically important entity in the management of shoulder instability. Smaller bony lesions may be amenable to arthroscopic treatment, but larger lesions often require open surgery to prevent recurrent instability [5]. There is evidence from multiple studies, although only level of evidence III–IV, that arthroscopic soft tissue repair for small glenoid bony fragments in an acute setting is associated with a successful treatment [5, 28, 29, 32]. Park et al. showed in a CT follow-up study that small bony Bankart fragments survived without resorption until 1 year postoperatively and that this soft tissue reattachment could survive [27]. The possibility of a Bankart repair combined with a so-called remplissage (filling up a Hill-Sachs defect with the help of the rotator cuff) is not discussed in this section as it is discussed in the previous chapter.

For bigger fragments and small Bankart fragments in chronic cases (>3 weeks post-trauma) as seen in Figs. 18.7 and 18.8, outcomes for soft tissue repairs were less favorable and associated with failure [5, 6, 24, 28]. This might be due to poor soft tissue quality or associated lesions that were not addressed during the repair (ALPSA or HAGL lesion) as those are linked with poorer outcomes [19, 26, 31].

Fig. 18.8

(Same patient as X-ray and Fig. 18.6) Only after debridement can the real size of the fragment be unveiled (black arrows)

Kim et al. published a study about treatment guidelines for arthroscopic repair according to the size of bony Bankart lesions of less than 25 % of the glenoid width [15]. For small lesions (<12.5 %), capsulolabral repair using suture anchors without excision of the bony fragment was performed. For medium lesions (12.5–25 %), anatomic reduction and fixation using suture anchors was performed, and the adequacy of reduction was assessed by CT postoperatively. The visual analog scale (VAS) for pain score and modified Rowe score for bony Bankart repair were compared and the postoperative recurrence rate investigated. They concluded that in small bony Bankart lesions, restoration of capsulolabral soft tissue tension alone was enough. However, in medium lesions, the osseous architecture of the glenoid should be reconstructed for more functional improvement and less pain [15].

A recent biomechanical study showed that 38–49 % of the contribution to stability was due to bony reconstruction of the glenoid area [43]. This is why several authors prefer an osseous glenoid reconstruction using the Latarjet, Bristow, or free bone graft technique [18, 21, 23, 36, 38, 39, 42, 44]. In the last 5 years, the all-arthroscopic techniques for bony augmentations such as the Latarjet or Bristow technique have been constantly evolving mostly out of France (Lafosse et al., Boileau et al., Figs. 18.9, 18.10, and 18.11) [3, 18]. These techniques combine the advantages of a bony augmentation and minimally invasive arthroscopy [17].

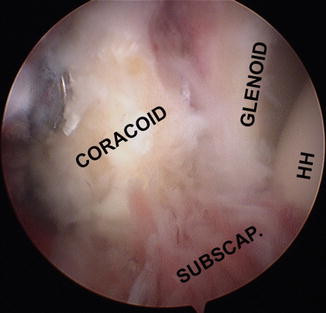

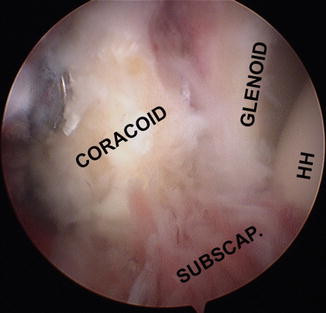

Fig. 18.9

This figure depicts an anterior view of the coracoid process attached to the glenoid to create a bony augmentation of the anterior glenoid rim. Also, the subscapularis tendon can be seen that, together with the conjoint tendon (left-hand lower corner), creates the sling effect

Rare indications are glenoid fractures with a single fragment after shoulder dislocations. In these circumstances, and if the fracture fragment is big enough, an acute reduction of the fragment using cannulated screws can be achieved [14, 28].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree