3.3 The respiratory system

Chapter 3.3a The physiology of the respiratory system

At the end of this chapter you will be able to:

Estimated time for chapter: 100 minutes.

The role of the respiratory system

The respiratory system is specialised to enable an adequate supply of oxygen to the tissues. As was described in Chapter 1.2b, oxygen is one of the essential ingredients for the process of cellular respiration. It is also the role of the respiratory system to allow carbon dioxide, a waste product of respiration, to be removed from the body.

Cellular respiration is the process (described in Chapter 1.2b) by which oxygen and nutrients are converted to cellular energy (adenosine triphosphate (ATP)) and carbon dioxide within the cell itself. It is important to be clear about the distinction between these three processes, as these terms help define the precise roles of the respiratory system.

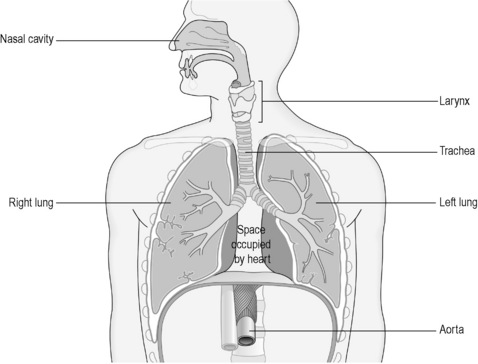

The respiratory system is conventionally divided into two sections, the upper and lower respiratory tract. A simple representation of the organs of the respiratory tract is given in Figure 3.3a-I. The division between the upper and lower parts occurs at the point at which the trachea splits into the two tubes called ‘bronchi’.

The upper respiratory tract

The pharynx

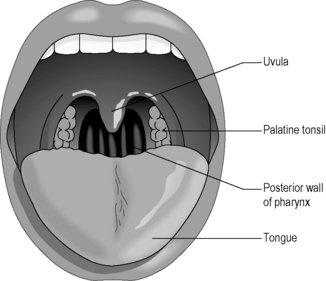

The pharynx is the space at the back of the nose that connects with the throat. The adenoids (nasal tonsils) are two collections of lymph-node tissue situated at the back of this space. The tonsils (palatine tonsils), which are similar collections of lymphoid tissue, are situated a little lower down. The palatine tonsils can be seen in most people on either side of the space behind the arch of the palate, as illustrated in Figure 3.1a-II, whereas the adenoids are hidden up behind the palatoglossal arch.

The larynx

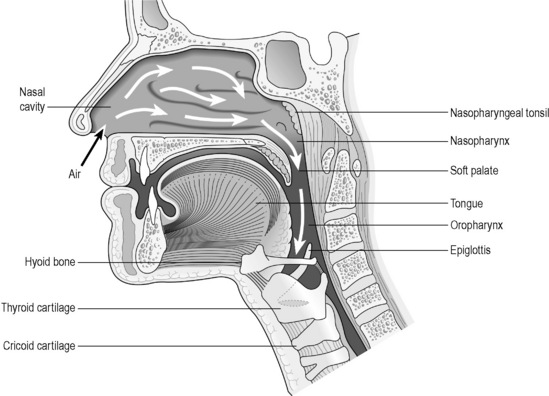

The larynx, popularly known as the voice box, is the structure that separates the pharynx from the trachea. Although it is primarily associated with voice production, it also plays a very important protective role. Figure 3.3a-III is a diagrammatic representation of the nasal cavity, pharynx and larynx, which illustrates how these structures relate to each other.

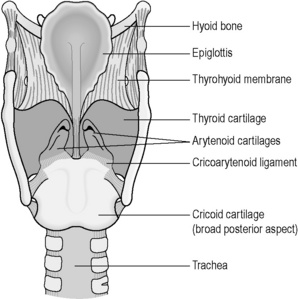

The vocal cords are two fine flaps of tissue that are suspended from the surrounding cartilage tube. Figure 3.3a-IV shows a view of the aperture of the larynx. The vocal cords are depicted on either side of the aperture, leaving a triangular space through which the air can pass. Tiny muscles in the larynx contract to change the shape of this triangle between the vocal cords so that the space can vary from being a wide gap to a tiny ‘chink’. The tone of the muscles also affects the tightness of the vocal cords. During quiet breathing the gap is wide to allow a free passage of air in and out of the lungs. During speech, the gap narrows and the cords tighten. The expired air causes vibration of the tightened cords, which produces the sound of the voice. The tighter the cords, the higher the pitch of the voice.

The lower respiratory tract

The alveoli

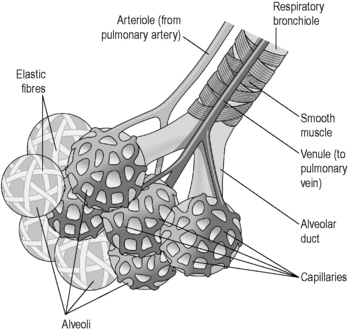

Figure 3.3a-V illustrates how the alveoli branch from the bronchioles, and how a network of capillaries supplies each one.

Exchange of gases in the alveoli

This process of exchange of gases is assisted by the fact that there are millions of alveoli, each with its own rich blood supply. In some conditions, such as emphysema, the delicate structure of the alveoli is damaged and their number is reduced (see Chapter 3.3e). This severely impairs the process of exchange of gases, so that the blood does not get replenished with an adequate amount of oxygen, and carbon dioxide fails to be fully cleared.

The lungs

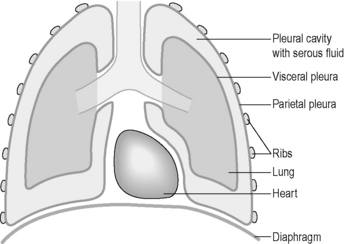

The lungs are surrounded by a double layer of protective fluid-secreting serous membrane called the ‘pleura’. In the pleura the secreted fluid forms a thin lubricating layer between the two pleural membranes akin to the fluid that separates the pericardium from the heart. The outer pleural membrane is attached to the inner surface of the rib cage from above and at the sides, and to the diaphragm below. It is this attachment that prevents the elastic lungs from collapsing. Figure 3.3a-VI illustrates the relationship between the pleura and the lungs.

External respiration

The way in which the brain is responsible for the voluntary and involuntary control of body functions is described in more detail in Chapter 4.1 on the nervous system (see Q3.3a-4) .

.

Information Box 3.3a-I The lungs: comments from a Chinese medicine perspective

Information Box 3.3a-I The lungs: comments from a Chinese medicine perspective

The functions of the Lungs are to:

Government of Qi and respiration refers to two aspects, as described below.

Summary

The functions of the Lung according to a conventional and Chinese perspective can be summarised in the form of a correspondence table (for an introduction to the Organ correspondence tables, see Appendix I). This table illustrates the idea that the functions of the air-filled sacs, which conventional medicine calls the lungs, may be the domain not only of the Lung Organ in Chinese Medicine, but also of the Kidney and Liver Organs. It will follow from this that diseases of the lungs may manifest in Chinese medicine syndromes involving the Lung, Liver and Kidney Organs.

Correspondence table for the functions of the Lung as described by conventional and Chinese medicine

Self-test 3.3a The physiology of the respiratory system

Self-test 3.3a The physiology of the respiratory system

1. What is the primary role of the respiratory system?

2. List three parts of the respiratory tract that would protect a person from smoke inhalation (NB: There are more than three.) Remember that smoke consists of tiny particles that are very irritating to the respiratory epithelium.

3. What is it that prevents the elastic lungs from collapsing in a healthy person?

Answers

1. The primary role of the respiratory system is external respiration. This involves the drawing in of clean, warm, moist air into the air spaces of the lungs so that the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide can take place between the outside air and the blood.

2. The lungs are protected from inhaled smoke by the following factors:

3. The lungs are protected from collapsing because the outer layer of the pleura is firmly attached to the rib cage, muscles and diaphragm, which comprise the inside of the walls of the thorax.

Chapter 3.3b The investigation of the respiratory system

The investigation of the respiratory system

The most common investigations of the respiratory system include:

• a thorough physical examination

• laryngoscopy to examine the vocal cords

• microscopic examination of the sputum

• lung-function tests to assess the mechanics of the breathing

• chest X-ray imaging, computed tomography (CT) scans and bronchoscopy to visualise the lungs

Physical examination

The physical examination of the respiratory system involves the stages listed in Table 3.3b-I.

Table 3.3b-I The stages of physical examination of the lungs

Computed tomography (CT) scan

Figure 3.3b-I shows a CT scan of the lungs in a patient with advanced lung cancer. This is a ‘slice’ of the upper chest presented as if the patient is lying on their back with their feet facing the viewer. The white structures are bones, and the sternum, one vertebral body, some ribs and the scapulae are visible. The very black areas are regions of normal air spaces in the lungs. The cancer is clearly seen as a grey shadow invading the normal lung tissue.

Biopsy of the lung tissue

Self-test 3.3b The investigation of the respiratory system

Self-test 3.3b The investigation of the respiratory system

1. Harry is 53 years old and has been smoking all his adult life. Recently he has become more breathless, and over the past 2 weeks has noticed blood in his sputum. His GP is concerned that Harry might have developed cancer and refers him for assessment by a chest physician. What tests do you expect Harry might have to undergo?

Answers

1. Harry will first be given a thorough physical examination. His fingers will be examined for clubbing and his tongue will be checked for cyanosis. The lymph nodes in the neck will be palpated to exclude any enlarged irregular nodes, which may occur in lung cancer. The rate and quality of his breathing will be assessed visually.

Harry will be given a chest X-ray and will be requested to produce a sample of sputum.

Chapter 3.3c Diseases of the upper respiratory tract

At the end of this chapter you will:

Estimated time for chapter: 100 minutes.

Acute infections of the upper respiratory tract

Sinusitis

Information Box 3.3c-I The common cold: comments from a Chinese medicine perspective

Information Box 3.3c-I The common cold: comments from a Chinese medicine perspective

From the integrated perspective of infectious disease introduced in Chapter 2.4d, the infectious viruses might be seen as the source of a Pathogenic Factor of external origin, whereas many bacterial complications of these infections would be seen as the result of additional Pathogenic Factors of internal origin. This is comparable to the concept in Chinese medicine that superficial invasions of Wind Heat or Wind Cold can progress to deeper levels in people with depleted Qi, and so fits in with the idea that in these cases the Pathogenic Factor is of internal origin.

Tonsillitis and pharyngitis

The treatment for bacterial tonsillitis is penicillin(phenoxymethyl) rather than amoxicillin. Often, a doctor might choose to prescribe penicillin in a severe case of tonsillitis, even when it is uncertain that the cause is bacterial. The delays involved in processing a throat swab and the discomfort for the patient deter many doctors from performing this test. This is an example of ‘treating blind’ (see Chapter 2.4d). In many cases it may never be known whether the antibiotic helped because the tonsillitis naturally gets better in most people by 3–7 days of onset.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. Information Box 3.3c-II

Information Box 3.3c-II Information Box 3.3c-III

Information Box 3.3c-III Information Box 3.3c-IV

Information Box 3.3c-IV Information Box 3.3c-V

Information Box 3.3c-V