1.3 Comparisons with alternative medical viewpoints

Chapter 1.3a Contrasting philosophies of health

At the end of this chapter you will be able to:

Estimated time for chapter: 90 minutes.

Conventional medicine as a reductionist system

However, there remain important differences, and these can lead to misunderstandings between practitioners of conventional medicine and practitioners of those complementary health disciplines that hold to a more holistic perspective. One author and alternative medicine practitioner has summarised the differences between ‘alternative medicine’ and conventional medicine as shown in Table 1.3a-I.

Table 1.3a-I A comparison between alternative and conventional medicine according to Gascoigne (2000)

| Alternative medicine | Conventional medicine |

|---|---|

| Energetic | Physical |

| Holistic | Separatist/reductionist |

| Transforms | Eliminates |

| Cures | Suppresses |

| Patient centred | Disease centred |

| Symptoms are useful pointers | Symptoms are to be removed |

| Disease is a group of symptoms (a syndrome) | Disease is a fixed entity |

| Cure is a move towards balance | Cure is removal of symptoms |

Tables 1.3a-II and 1.3a-III summarise some of the potential advantages and disadvantages of seeking treatment from complementary and conventional medical practices. These lists have been drawn up from a patient’s perspective. Not all patients want to be actively involved in their treatment, nor wish to have their world view challenged, and both these things may occur in some complementary therapies. This explains why a statement such as ‘Requires the patient to be active in changing lifestyle to enable healing’ is listed as a possible disadvantage of complementary therapy, and ‘Treatment is not expected to challenge the patient at a deep level’ as a possible advantage of conventional medical treatment.

Table 1.3a-II Complementary medical treatment: advantages and disadvantages

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

Table 1.3a-III Conventional medical treatment: advantages and disadvantages

Self-test 1.3a Contrasting philosophies of health

Self-test 1.3a Contrasting philosophies of health

1. Write down your own definitions of the words ‘reductionist’ and ‘holistic’ as used to describe philosophies of health.

2. Alice is a gardener and has a lot of work to do. She is finding that hay fever is really reducing the effectiveness of her work. The antihistamine tablets prescribed by her doctor do not seem to touch the problem. She turns to acupuncture as she has heard it has good results in hay fever.

How do you feel Alice’s philosophy of health may affect her first experience of acupuncture?

Answers

1. Your definitions could be similar to the following:

2. It is likely that Alice has a conventional view of health, as her first choice for treatment was the conventional drug, an antihistamine. She may well be hoping that acupuncture can likewise suppress her uncomfortable symptoms and let her get on with her life. This could have the following consequences:

Chapter 1.3b Drugs from a complementary medical viewpoint

Chapter 1.2c introduced a method of categorising drugs by mode of therapeutic action and the concept of iatrogenic disease (illness as a result of medical treatment). This chapter presents some complementary perspectives on the beneficial and adverse effects of drugs in the body. It also describes some principles of mapping Chinese medicine concepts to western medical theory. These are explored in some detail under the heading ‘The Rationale and Method Used for the Mapping of Western Medical Diagnoses to Chinese Medicine Theory’ in the Note to the Reader contained in the preliminary pages of this book.

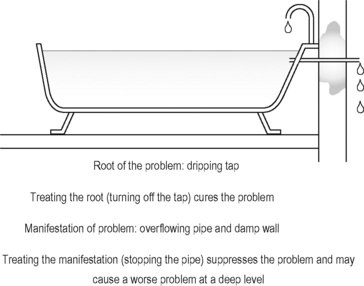

Suppression of symptoms

Figure 1.3b-I illustrates the complementary medicine concept of suppression. The bathtub with a running tap has a problem; it is leading to a dripping overflow pipe, and thus causing damp to the exterior wall. This ideally would be treated by turning off the taps, the root of the problem. However, someone outside the house might be tempted to deal with the manifestation of the problem. They could stop the dripping overflow and allow the wall to dry out by blocking the overflow pipe with a cork. This treatment would indeed solve the problem of the dripping pipe, but of course would result in a more catastrophic problem inside the house as the bath then proceeds to overflow onto the bathroom floor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

.

. .

. .

. .

.