The knee is a synovial hinge joint, supported and stabilized by powerful muscular and ligamentous forces. It is superficial on three sides (anterior, medial, and lateral), and approaches to it are comparatively straightforward. Because the knee joint is only covered by skin and retinaculae on three of its four sides, the joint is ideal for arthroscopic approaches. Arthroscopy of the knee is also facilitated by the large size of the joint cavity. Arthroscopic approaches have largely replaced open surgical approaches for the treatment of meniscal pathology, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, and removal of loose bodies.

Two arthroscopic approaches are described that allow complete exploration of the knee joint.

Seven open approaches to the knee are described. These approaches are useful where arthroscopic equipment is not available. They are also of great importance when dealing with trauma of the knee joint associated with open wounds. Because the major neurovascular structures of the leg all pass posterior to the joint, the posterior approach is used mainly for exploration of these structures.

The medial parapatellar approach, the most common knee incision, can be used for a variety of procedures. The length of the incision depends on the pathology to be treated; when it is used fully, this approach gives an unrivaled exposure of the whole joint. It is suitable for total joint replacement.

The approach for medial meniscectomy is much more restricted. The introduction of the operative arthroscope has limited its use.

The medial approach to the knee joint affords easier access to the medial supporting structures of the knee. Because of its slightly more posterior placement and the curving nature of the approach, a flap can be developed that allows better visualization of the posteromedial corner of the joint.

The anatomy of the medial side of the knee is considered in a separate section after these approaches are described.

The approach for lateral meniscectomy provides adequate exposure, but its use is limited. The lateral approach is used for ligamentous reconstruction of the knee’s lateral supporting structures. The anatomy of the knee’s lateral side is considered after these two approaches are outlined.

The lateral approach to the distal femur, an adjunct to the medial parapatellar incision, is used for repairs of ruptured anterior cruciate ligaments. The approach enters the intercondylar notch from behind, allowing reattachment of the distal stump of a torn anterior cruciate ligament or the insertion of a graft. It usually is used in conjunction with an anteromedial approach to the knee.

The posterior approach to the knee is performed rarely, and when it is, it is usually for the repair of neurovascular structures. Its anatomy is considered after this approach is described.

General Principles of Arthroscopy

See Chapter 1, General Principles of Arthroscopy, Figs. 1-68, 1-69 and 1-70.

Arthroscopic Approaches to the Knee

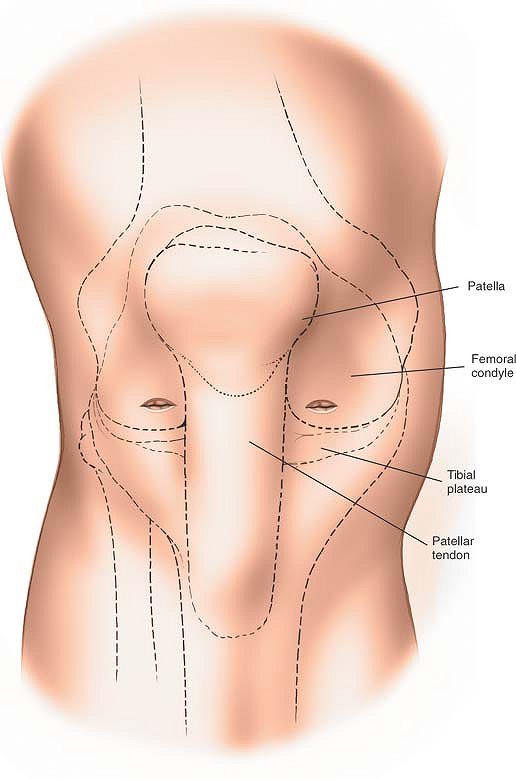

The knee is a large unconstrained hinge joint that is often described as subcutaneous. Its anteromedial and anterolateral coverings consist largely of fibrous tissue—the patellar retinaculum and joint capsule (see Figs. 10-40, 10-54). Incisions through these coverings can be safely made without endangering any vital structures.

Arthroscopy of the knee has largely replaced open procedures for the following:

Meniscal resection or repair

Removal of loose bodies

Anterior or posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

Synovial biopsy

P.511

Synovectomy

Debridement of early osteoarthritic knees, including microfracture

Treatment of osteochondritis dissecans

Numerous arthroscopic portals have been described in knee arthroscopy surgery.1,2

The anterolateral portal is the one most commonly used for diagnostic purposes; it is nearly always used in conjunction with the anteromedial portal. The combination of these approaches allows the use of the arthroscope along with arthroscopic instrumentation. Usually the arthroscope is inserted via the anterolateral portal and instruments are inserted via the anteromedial portal. However, either portal can be used for either purpose. These two approaches are described in this section.

|

Figure 10-1 Place the patient supine on the operating table. Remove the end of the table so that you are able to manipulate the knee during surgery. |

Position of the Patient

Place the patient supine on the operating table. Apply a well-padded tourniquet to the mid-thigh. Exsanguinate the limb and inflate the tourniquet. Remove the end of the table (Fig. 10-1; see Figs. 10-9 and 10-41). Prep and drape the limb so that you

are able to manipulate the knee during surgery. The use of an arthroscopic clamp placed around the tourniquet allows the surgeon to apply a valgus and external rotation force to the knee, facilitating access to the medial compartment. The use of a clamp, however, makes it more difficult to place the knee in the figure-of-eight position (placing the lateral malleolus of the involved extremity on the opposite thigh; see Figs. 10-8, inset, and 10-42) to allow access to the lateral compartment of the knee. If a surgical assistant is available to provide the appropriate forces, the use of a clamp is not indicated.

P.512

are able to manipulate the knee during surgery. The use of an arthroscopic clamp placed around the tourniquet allows the surgeon to apply a valgus and external rotation force to the knee, facilitating access to the medial compartment. The use of a clamp, however, makes it more difficult to place the knee in the figure-of-eight position (placing the lateral malleolus of the involved extremity on the opposite thigh; see Figs. 10-8, inset, and 10-42) to allow access to the lateral compartment of the knee. If a surgical assistant is available to provide the appropriate forces, the use of a clamp is not indicated.

|

Figure 10-2 Lateral incision: make a small 8-mm transverse stab incision 1½ cm above the lateral joint line. Medial incision: make an 8-mm stab incision 1½ cm above the medial joint line. |

Landmarks and Incision

Lateral

Flex and extend the knee and use your thumb to palpate the lateral joint lines. Move your thumb toward the midline. You will feel the resistance of the lateral edge of the patellar tendon. Flex the knee to 90°. Place your

forefinger in the recess created by the lateral border of the patellar tendon and the lateral joint space. This is the so-called soft spot. Make an 8-mm transverse stab incision approximately 5 mm proximal to your finger, 1 cm to 1½ cm above the joint line (Fig. 10-2).

P.513

forefinger in the recess created by the lateral border of the patellar tendon and the lateral joint space. This is the so-called soft spot. Make an 8-mm transverse stab incision approximately 5 mm proximal to your finger, 1 cm to 1½ cm above the joint line (Fig. 10-2).

Medial

Move your finger to palpate the medial joint line and the medial edge of the patellar tendon. Place your finger in the medial soft spot, and make an 8-mm stab incision some 1½ cm above the joint line. Note that because the lateral tibial plateau is slightly lower than the medial plateau, the lateral incision will be slightly lower than the medial one (see Fig. 10-2).

Internervous Plane

There is no internervous plane in these surgical approaches, which consist of incisions made in the medial and lateral patellar retinacula and joint capsule. No major nerves are present in these areas.

Surgical Dissection

With the knee flexed to 90°, deepen the anterolateral skin incision using a sharp-ended blade. As you incise the retinaculum, you will suddenly feel a decrease in resistance. Withdraw the blade and insert the arthroscopic sheath and blunt trochar. Push the sheath and trochar into the anterolateral portion of the knee, taking care not to hit the underlying femur; then carefully extend the knee while advancing the arthroscopic sheath up into the suprapatellar pouch. Remove the trochar. Insert the 30° arthroscopic telescope. Switch on the irrigation fluid before switching on the light source to avoid thermal damage to the synovium.

Arthroscopic Exploration of the Knee

Although the use of a preoperative MRI facilitates the discovery of pathology within the knee, it is important to ensure that each arthroscopic exploration examines all portions of the knee and not merely the site of the presumed pathology.

Order of Scoping

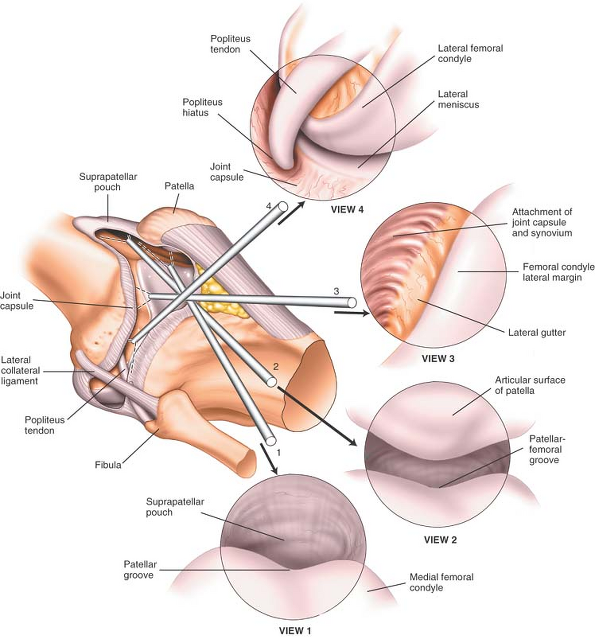

Begin with placing a 30° arthroscope in the suprapatellar pouch (Fig. 10-3, view 1). The arthroscope should be easily mobile, allowing you to examine all portions of the suprapatellar pouch, noting especially the synovium and checking for the presence of any loose bodies.

Keeping the knee fully extended, withdraw the arthroscope into the patellofemoral joint, rotating the telescope to allow examination of both the femoral and patellar aspects of the joint (see Fig. 10-3, view 2). Manipulating the patella medially and laterally facilitates this procedure.

Keeping the leg extended, slide the tip of the arthroscope into the lateral recess or gutter of the knee, passing the scope between the lateral aspect of the femur and the lateral capsule of the joint (see Fig. 10-3, view 3). Observe the lateral surface of the femur, and ensure that you can see the insertion of the popliteus muscle (see Fig. 10-3, view 4). The popliteal hiatus is a common recess for the presence of loose bodies.

Keeping the knee in full extension, sweep the arthroscope into the lateral portion of the knee, observing the anterior part of the lateral meniscus (Fig. 10-4, view 5). Pass the arthroscope medially, and rotate the scope so that you are looking posteriorly. This will allow you visualization of the medial femoral recess or gutter (see Fig. 10-4, view 6).

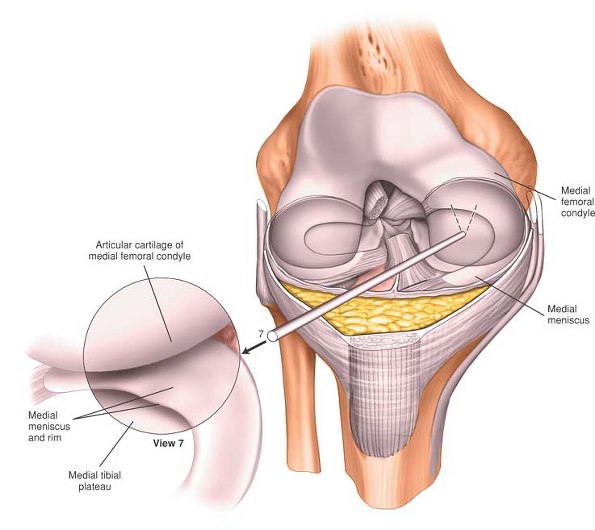

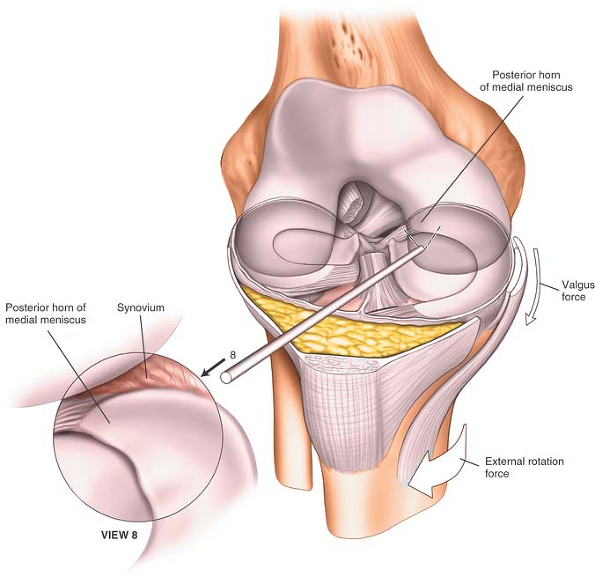

Withdraw the arthroscope into the center of the knee and gently flex to 90°, allowing the tip of the arthroscope to enter the medial compartment of the knee. Observe the articular cartilage of the medial femoral condyle and medial tibial plateau. Also observe the medial meniscus and meniscal rim (Fig. 10-5, view 7). Apply a valgus and external rotation force to the knee, and rotate the scope so that it is looking laterally, to allow examination of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (Fig. 10-6, view 8).

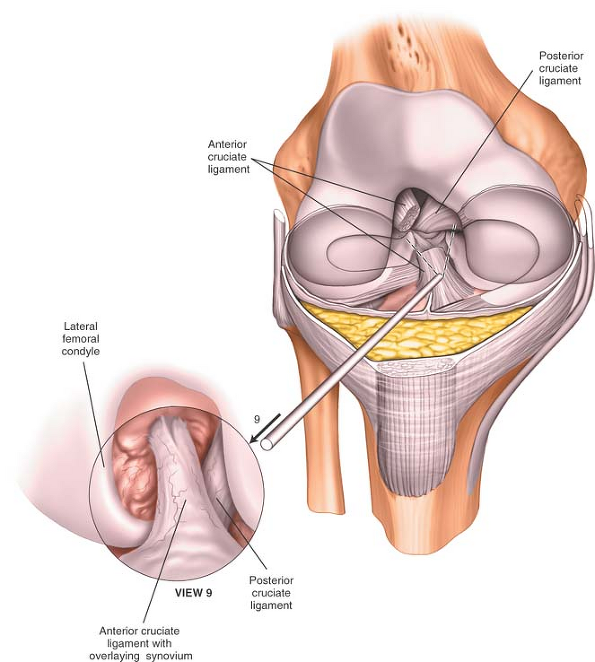

Withdraw the arthroscope into the intercondylar notch, observing the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (Fig. 10-7, view 9).

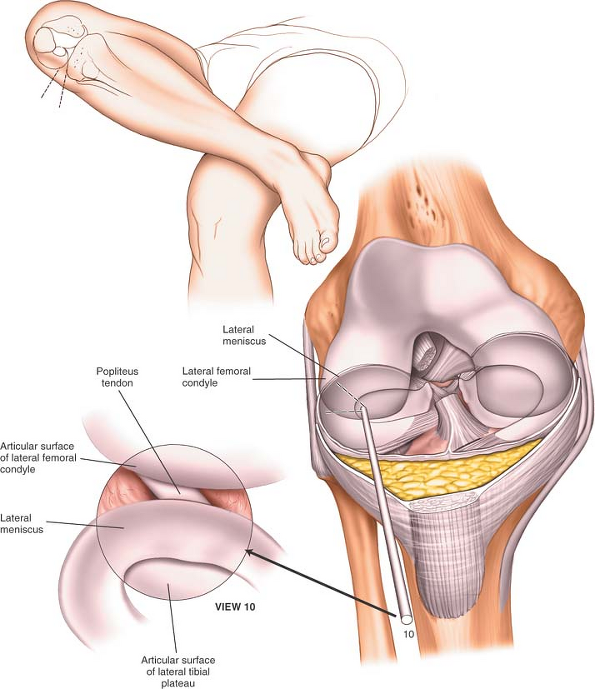

With the arthroscope in the area of the intercondylar notch, flex the knee to just over 90°, abduct the hip, and place the lateral malleolus of the operative side on the anterior aspect of the contralateral knee (see Fig. 10-42). This is known as the figure-of-eight position and allows arthroscopic inspection of the entire lateral compartment (Fig. 10-8, inset). Observe the articular surfaces of the lateral femoral condyle and lateral tibial plateau. Examine the lateral meniscus in its entirety (see Fig. 10-8, view 10).

P.514

|

Figure 10-3 (View 1) Begin with the arthroscope in the suprapatellar pouch and observe the synovium, checking for the presence of loose bodies. (View 2) Withdraw the arthroscope into the patellofemoral joint. To observe the full extent of the joint, rotate the scope in both directions and move the patella medially and laterally. (View 3) Slide the scope into the lateral recess of the knee and observe the lateral aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. (View 4) Advance the arthroscope into the lateral gutter to view the insertion of the popliteal muscle. |

P.515

|

Figure 10-4 (View 5) With the knee in full extension, sweep the arthroscope into the lateral portion of the knee and observe the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus and the anterior part of the lateral femoral condyle. (View 6) Advance the arthroscope medially and rotate it to look posteriorly. Observe the medial femoral recess. |

P.516

|

Figure 10-5 (View 7) Withdraw the arthroscope into the center of the joint, and then flex the knee to allow the arthroscope to enter the medial compartment. Observe the rim of the medial meniscus, the medial femoral condyle, and the medial tibial plateau. |

P.517

|

Figure 10-6 (View 8) Apply a valgus/external rotation force to the knee, and rotate the arthroscope so that it is looking laterally. Observe the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. |

P.518

|

Figure 10-7 (View 9) Withdraw the arthroscope into the intercondylar notch to observe the cruciate ligaments. |

P.519

|

Figure 10-8 (Inset) Flex the knee 90° above the hip, and place the lateral malleolus of the operative side on the anterior aspect of the contralateral knee (figure-of-eight position). (View 10) Advance the arthroscope into the lateral compartment of the knee to observe the lateral meniscus in its entirety. |

P.520

To allow inspection of the undersurface of the menisci and to assess the integrity of the cruciate ligaments, insert the arthroscopic hook through the anteromedial portal and use it under direct vision of the arthroscope to palpate these structures.

Dangers

Articular Cartilage

The articular cartilage of the knee may be damaged at two stages during arthroscopy: by the incision or by the forceful insertion of an arthroscope. If the incision is made carefully, this problem should not occur. Remember that if you meet with resistance when manipulating the arthroscope within the knee, then it is certain that you are damaging the articular cartilage. More posteriorly based incisions on the medial side may easily damage the articular surface of the medial femoral condyle if performed blind. Therefore, it is recommended that more posterior medial or lateral incisions, if needed, should be made under direct arthroscopic control. Ten seconds of careless use of an arthroscope within the knee may create the equivalent of 10 years of wear in that joint.

Meniscus

The meniscus may be damaged by the scalpel or the arthroscope if the incisions are made too close to the joint line.

How to Enlarge the Approach

Local Measures

Manipulation of the knee is the key to success in visualizing all portions of the joint. To allow complete inspection of the knee, apply a valgus external rotation force to assess the posterior aspect of the medial compartment of the knee. You will also need to apply a varus internal rotation stress to examine the lateral portions of the knee. Remember that the telescope you use is angled at 30°. Changing the direction of the telescope will therefore significantly change the view that you obtain (see Figs. 1-68, 1-69 and 1-70). This is most important when examining the posterior third of the medial compartment of the knee.

Medial Parapatellar Approach

The medial parapatellar approach3 is the workhorse approach to the knee. Extended to its full length, it allows excellent access to most structures. Portions of the incision can be used to gain access to the supra-patellar pouch, the patella, and the medial side of the joint. When a straight, midline, longitudinal skin incision is used in conjunction with a medial parapatellar capsular approach, the incision offers an exposure large enough for total knee arthroplasty.

Minimal access approaches have been described for the insertion of total knee replacements where the patella is not dislocated. Such approaches may significantly reduce the damage done to the extensor mechanism by the surgery and reduce the amount of postoperative scarring that occurs in the suprapatella pouch. Such approaches, however, limit visualization of the distal femur, making accurate positioning of implants more difficult. Additional imaging, especially computer-assisted surgery, may be helpful if these approaches are used for total knee replacement.

The uses of the medial parapatellar approach include the following:

Synovectomy4,5

Medial meniscectomy

Removal of loose bodies6

Ligamentous reconstructions

Patellectomy

Drainage of the knee joint in cases of sepsis

Total knee replacement7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14

Repair of the anterior cruciate ligament (see the section regarding the lateral approach to the distal femur)

Open reduction and internal fixation of distal femoral fractures when a medial plate is to be used

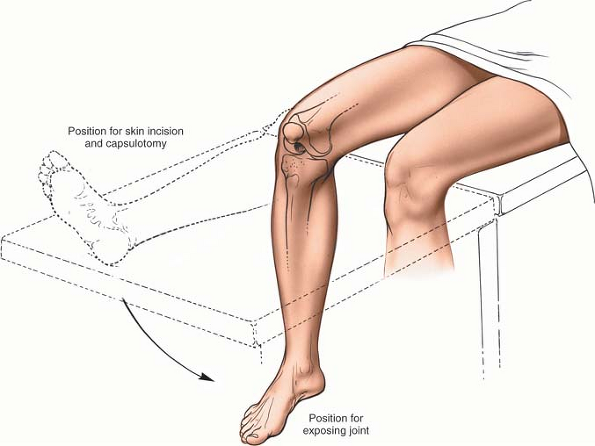

Position of the Patient

Place the patient in a supine position on the operating table. The approach can be made with or without the use of a tourniquet. Operating without a tourniquet slows the surgical approach, but bleeding points are easy to pick up in the superficial surgical dissection. If you are using a tourniquet, it will need to be removed prior to closure of the wound to allow you to obtain hemostasis of the wound. If you are using a tourniquet, exsanguinate the leg by applying a compressive bandage or by elevating the limb for five minutes; then, inflate a tourniquet (Fig. 10-9).

Place a sandbag on the table in such a position that it supports the heel when the knee is flexed to 90°. This sandbag will help maintain the knee in

a flexed position during joint replacement surgery. Position a table support on the outer aspect of the upper thigh to prevent the leg from falling into abduction when the knee is flexed.

P.521

a flexed position during joint replacement surgery. Position a table support on the outer aspect of the upper thigh to prevent the leg from falling into abduction when the knee is flexed.

|

Figure 10-9 Position of the patient for the medial parapatellar approach. Begin with the straight leg position, and then flex the knee for the deeper dissection. |

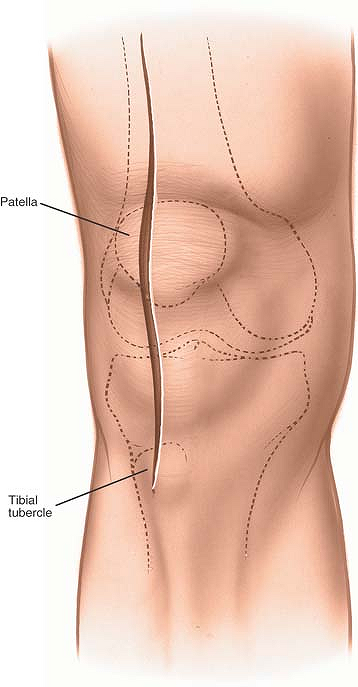

Landmarks and Incision

Landmarks

Palpate the patella. Run fingers down to the patellar ligament (ligamenta patellae), which runs from the inferior border of the patella and is palpable to its insertion into the tibial tubercle.

Incision

Make a longitudinal straight midline incision, extending from a point 5 cm above the superior pole of the patella to below the level of the tibial tubercle (see Fig. 10-10).

Internervous Plane

There is no internervous plane in this approach, even when the incision is extended superiorly into the intermuscular plane between the vastus medialis and rectus femoris muscles. Both of these muscles are supplied by the femoral nerve well proximal to this dissection, leaving the plane safe for knee surgery.

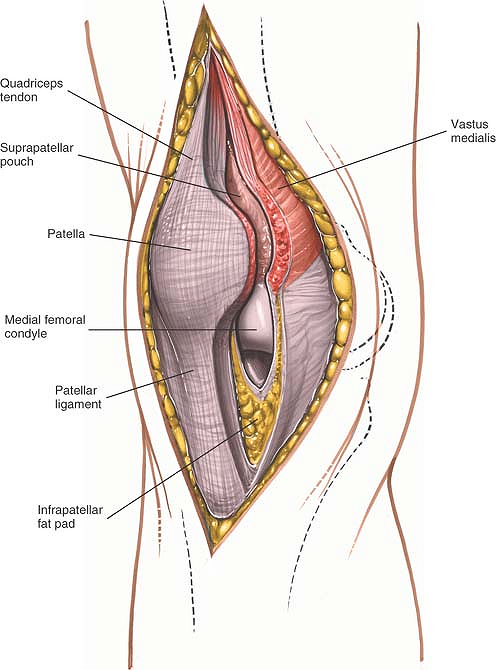

Superficial Surgical Dissection

Divide the subcutaneous tissues in the line of the skin incision, ensuring hemostasis. Develop a medial skin flap to expose the quadriceps tendon, the medial border of the patella, and the medial border of the patellar tendon. Enter the joint by cutting through the joint capsule. Begin on the medial side of the patella, taking care to leave a cuff of capsular tissue medial to the patella and lateral to the quadriceps muscle to facilitate closure. Divide the quadriceps tendon in the midline to enter the suprapatellar pouch. Finally, complete the capsule incision by dividing the fibrous tissue on the medial aspect of the patellar tendon. The capsular incision will almost certainly also cut through the synovium, since the capsule and synovium are intimately related.

Retract the fat pad, or excise it, as dictated by the exposure requirements. As the joint line is approached, care should be taken not to damage the anterior insertion of the medial meniscus unless the approach is being used for joint replacement surgery (Figs. 10-10, 10-11 and 10-12).

P.522

|

Figure 10-10 Make a longitudinal, straight, midline incision. |

P.523

|

Figure 10-11 Make a medial parapatellar capsular incision. |

P.524

|

Figure 10-12 Continue the incision through the joint capsule and along the patellar ligament and quadriceps tendon to gain access to the joint. |

P.525

Deep Surgical Dissection

Dislocate the patella laterally and rotate it 180°; then, flex the knee to 90° (Fig 10-13; see Fig. 10-9). Try to avoid avulsion of the patellar ligament from its insertion on the tibia as the patella is dislocated, because reattaching the tendon to the bone is difficult. If the patella does not dislocate easily, it can be given added mobility by extending the skin incision superiorly over the interval between the rectus femoris and vastus medialis muscles. Continue the dissection deeper, splitting the quadriceps tendon farther just lateral to its medial border (see Fig. 10-13).

In the case of revision surgery, the suprapatella pouch is reduced in size or may actually be obliterated. Careful sharp dissection through the scar tissue may significantly improve the mobility of the patella, which allows greater flexion of the knee and eversion of the patella.

|

Figure 10-13 Dislocate the patella laterally, and flex the knee to 90°. |

In those rare cases in which the patella still does not dislocate, carefully remove the patellar ligament attachment with an underlying block of bone. The bone makes subsequent reattachment easier (Fig. 10-14). Be aware that the tibial components of many knee replacements incorporate a central peg that makes reattachment of a bone block impossible if a screw is to be used. In such cases, a staple fixation may be indicated.

When the patella is dislocated and the knee is flexed fully, this incision provides the widest possible exposure of the entire knee joint.

P.526

|

Figure 10-14 Detach the patellar ligament attachment with an underlying block of bone. |

Dangers

Nerves

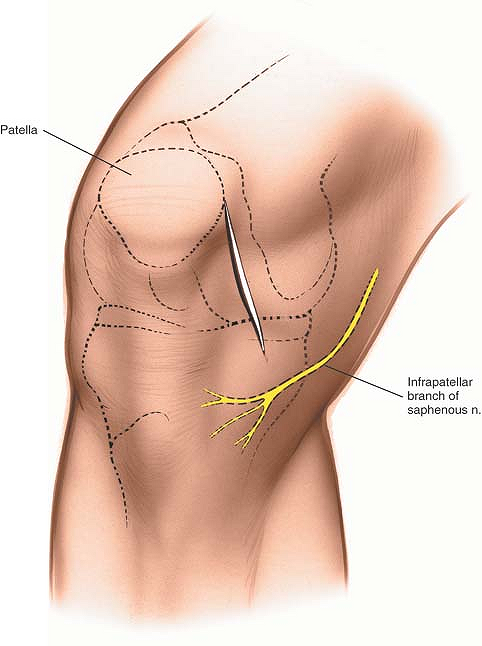

The infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve often is cut during this approach. The major danger in cutting the nerve is the development of a postoperative neuroma. Because the area of anesthesia produced usually is not troublesome, do not repair the nerve if it is cut. Instead, resect it and bury its end in fat to decrease the chances that a painful neuroma will form (see Figs. 10-32 and 10-35).

Muscles and Ligaments

If the patellar ligament becomes avulsed from its insertion on the tibia, it is difficult to reattach.

How to Enlarge the Approach

Local Measures

Superior Extension. Extend the approach proximally between the rectus femoris and vastus medialis muscles. Then, split the underlying vastus intermedius muscle to expose the distal two thirds of the femur. Stay in the distal third of the thigh; more proximally, the branches of the femoral nerve may become involved, resulting in partial denervation (see Anteromedial Approach to the Distal Two Thirds of the Femur in Chapter 9, see Figs. 9-16, 9-17, 9-18, 9-19 and 9-20).

Inferior Extension. Mobilize the upper part of the attachment of the patellar ligament to the tibia or remove the patellar ligament with an underlying block of bone. This extension may be useful in dealing with complex intraarticular fractures of the knee joint. (See the section detailing the lateral approach to the distal femur for combined use in repair of the cruciate ligament.)

Approach for Medial Meniscectomy

The approach for medial meniscectomy15 is a common formal incision for the knee. It is quite flexible, with several acceptable locations for incision and many different ways to position the patient. Some surgeons advocate a transverse skin incision over the joint line; although this limits the view of the knee, it provides better access to the meniscus itself. Others prefer longitudinal or oblique incisions, which offer a better view of such other intraarticular structures as the cruciate ligaments. Although operative arthroscopy has reduced dramatically the need for this approach, it remains a useful one in those many parts of the world where arthroscopy is not available.

The uses of the anteromedial approach include the following:

Medial meniscectomy

Partial meniscectomy

Removal of loose bodies

Removal of foreign bodies

Treatment of osteochondritis of the medial femoral condyle6

P.527

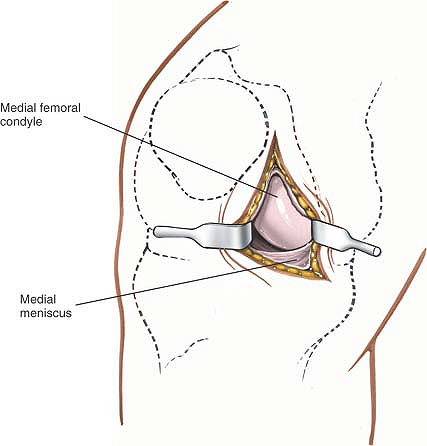

Position of the Patient

Arrange the patient in a supine position on the operating table. Place a sandbag under the affected thigh, taking care that it is not directly beneath the popliteal fossa, where it will compress the popliteal artery and posterior joint capsule against the back of the femur and tibia, increasing the risk of accidental injury during excision of the posterior third of the meniscus (Fig. 10-15). Remove the end of the table so that the knee can be flexed beyond a right angle.

This position requires good lighting so that the meniscus can be seen during surgery. The light must be adjusted continually to keep it shining directly into the depths of the wound. A headlamp is the best light source.

|

Figure 10-15 (A) Position of the patient for medial meniscectomy. (B) Improper placement of the sandbag pushes the popliteal artery against the posterior joint capsule. (C) Proper placement of the sandbag under the affected thigh. |

Exsanguinate the limb by elevating it for 2 to 5 minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage. Then, apply a tourniquet.

Landmarks and Incision

Landmarks

The medial joint line must be identified, because incisions easily can be made too high. Flexion and extension of the knee allows the line to be palpated with certainty.

Locate the inferomedial corner of the patella.

Incision

Begin the incision at the inferomedial corner of the patella. Angle it inferiorly and posteriorly, ending about 1 cm

below the joint line. Incisions continued farther inferiorly can cut the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve as it traverses the upper leg (Fig. 10-16).

P.528

P.529

below the joint line. Incisions continued farther inferiorly can cut the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve as it traverses the upper leg (Fig. 10-16).

|

Figure 10-16 Incision for anteromedial approach for medial meniscectomy. |

|

Figure 10-17 Incise down to the anteromedial aspect of the joint capsule. |

|

Figure 10-18 Incise the joint capsule in line with the incision to reveal the extrasynovial fat. |

Internervous Plane

There is no internervous plane in this approach because the deep incision is made through the medial patellar retinaculum and joint capsule.

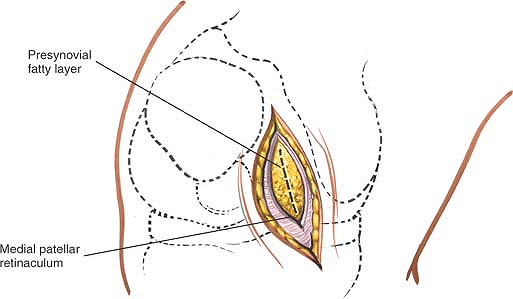

Superficial Surgical Dissection

Deepen the wound in line with the skin incision down to the anteromedial aspect of the joint capsule, the true joint capsule, which is reinforced by the medial retinaculum of the patella (Fig. 10-17). Incise the capsule in line with the skin incision, which also is in line with the capsular fibers (Fig. 10-18).

|

Figure 10-19 Incise the synovium to gain access to the joint. |

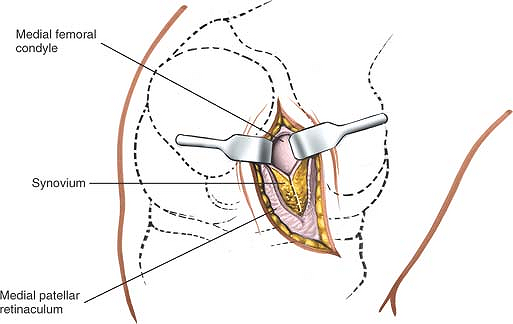

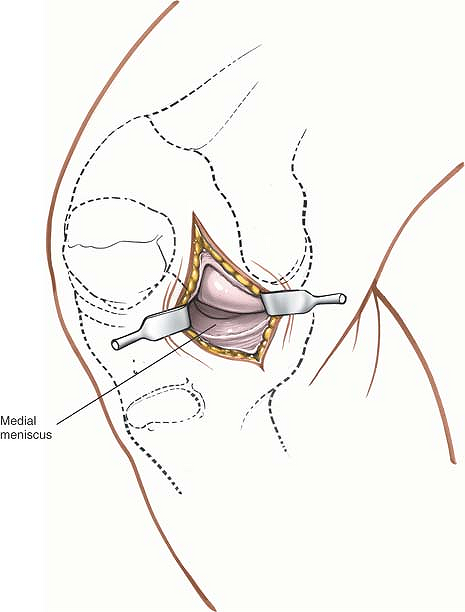

Deep Surgical Dissection

Open the synovium, together with the extrasynovial fat, well above the joint line to gain access to the anteromedial portion of the joint (Fig. 10-19). Opening the joint above the joint line avoids damage to the intrasynovial fat pad, medial meniscus, and coronary ligament (Figs. 10-20 and 10-21).

P.530

|

Figure 10-20 Open the joint capsule and synovium to the joint line to prevent damage to the meniscus and synovial fat pad. |

Dangers

Nerves

The infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve may be cut if the incision is extended farther inferiorly than 1 cm below the joint line (see Fig. 10-16).

Vessels

Because the popliteal artery is immediately behind the posterior joint capsule, any injury to the posterior joint capsule may damage the artery. If the knee is flexed, the posterior joint capsule falls away from the tibia and femur, taking the artery with it. A sandbag placed directly under the popliteal fossa prevents the capsule from moving posteriorly and must be avoided at all costs (see Fig. 10-15B,C).

Muscles and Ligaments

The coronary ligament (the meniscotibial element of the deep medial ligament) connects the periphery of the meniscus with the joint capsule and tibia, and may be damaged if the incision through the synovium is made at the joint line (see Figs. 10-33 and 10-34).

Incisions made too far posteriorly may cut the superficial medial ligament (the tibial collateral ligament) as it runs from the medial epicondyle of the femur to its insertion on the tibia under cover of the pes anserinus (see Figs. 10-27 and 10-28).

Special Structures

The fat pad occupies varying amounts of the anterior portion of the knee joint and should not be damaged. Damage may produce adhesions within the joint and, in theory, can interfere with the blood supply to the patella (see Fig. 10-12).

The medial meniscus may be incised accidentally during the opening of the synovium unless the knee joint is entered well above the joint line.

How to Enlarge the Approach

Local Measures

Three factors may improve the exposure offered by this approach:

P.531

|

Figure 10-21 Flex the knee and use retractors to gain further access to the meniscus. |

Retraction. Retractors must be positioned and repositioned carefully to ensure the best possible view of the intraarticular structures.

Position of light. Light should shine directly into the wound, usually from over the surgeon’s shoulder. Constant readjustment is necessary, and the use of a headlamp is invaluable.

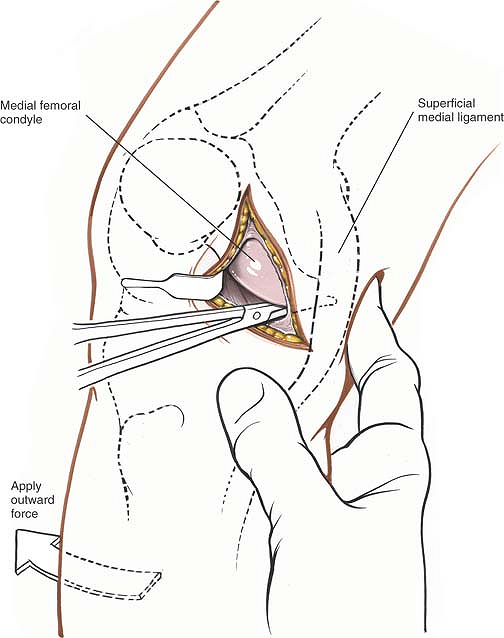

An outward stress will open up the medial side of the joint. Flexion of the knee allows better access to the back of the medial side of the joint. If the posterior horn of the medial meniscus must be seen, however, a better view is obtained by putting the leg into full extension and applying distraction and outward force. However, visualization of the peripheral parts of the posterior horn is always very limited in this surgical approach.

Extensile Measures

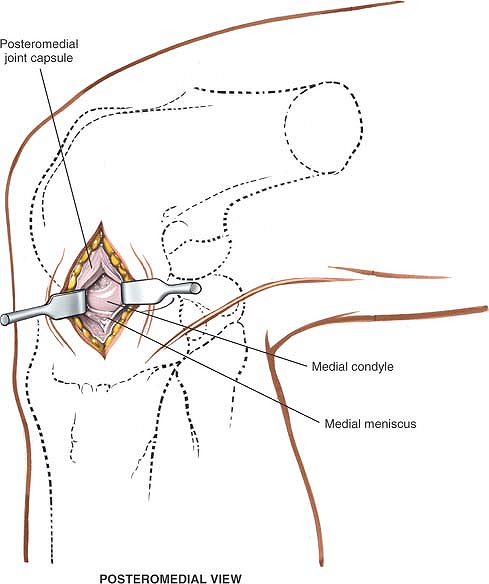

Posterior Extension. The dissection is limited posteriorly by the superficial medial ligament, which crosses the joint just in front of the midpoint of the femur. For better access to the posterior half of the joint, a second incision must be made behind this ligament. This is usually only required for excision of a retained posterior horn.

Insert a blunt instrument into the joint and push it slowly backward, running along the inside of the medial joint capsule at the level of the joint itself. As the instrument is pushed, the superficial medial ligament will be sensed; from inside the knee, it feels like a firm structure beneath the tip of the instrument. As the instrument is passed posteriorly,

there will be a give in the resistance corresponding to a point just posterior to the superficial medial ligament (Fig. 10-22). At that point, make a second longitudinal posterior incision through the skin and knee joint capsule (Fig. 10-23).

P.532

there will be a give in the resistance corresponding to a point just posterior to the superficial medial ligament (Fig. 10-22). At that point, make a second longitudinal posterior incision through the skin and knee joint capsule (Fig. 10-23).

|

Figure 10-22 Insert a blunt instrument into the joint, and push it backward along the inside of the medial joint capsule. Palpate posteriorly until the instrument can be felt beneath the skin. |

Superior Extension. To extend the incision superiorly, continue incising the skin along the medial border of the patella. Then, incise the medial patellar retinaculum and the underlying joint capsule in the same line to reach the back of the patella. Further superior extension exposes the suprapatellar pouch, which is a frequent site of loose bodies in the knee.

The incision may be extended still farther proximally in the muscular plane between the vastus medialis and rectus femoris muscles, exposing the distal two thirds of the femur.

Inferior Extension. Inferior extension can cut the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve and is not recommended.

P.533

|

Figure 10-23 Make a second longitudinal posterior incision to enter the posteromedial aspect of the joint. |

Medial Approach to the Knee and Its Supporting Structures

The medial approach16 provides the widest possible exposure of the ligamentous structures on the medial side of the knee. Although it is used mainly for the exploration and treatment of damage to the superficial medial (collateral) ligament and medial joint capsule, the approach also can be used for a medial meniscectomy in conjunction with ligamentous repair and for the repair of a torn anterior cruciate ligament. (See the section regarding the lateral approach to the distal femur.)

Position of the Patient

Place the patient supine on the operating table. Flex the affected knee to about 60°. Abduct and externally rotate the hip on that side, placing the foot on the opposite shin. Then, use a tourniquet after exsanguinating the limb. Various thigh rests have been designed to make it easier to maintain this position (Fig. 10-24).

Landmark and Incision

Landmark

Palpate the adductor tubercle on the medial surface of the medial femoral condyle. It lies on the posterior part of the condyle in the distal end of the natural depression between the vastus medialis and hamstring muscles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree