Operations on the femur are extremely common. The lateral approach to the proximal femur, which is used to treat the growing number of patients who have intertrochanteric hip fractures, is the most frequently used approach in orthopaedic surgery.

The four basic approaches to the femoral shaft, the lateral, posterolateral, anterolateral, and anteromedial, all penetrate elements of the quadriceps muscle. Only the posterolateral approach uses an internervous plane, but all are relatively straightforward because the femoral nerve, which supplies the quadriceps femoris muscle, divides proximally in the thigh, allowing the more distal muscle elements to be separated without denervation. (The posterior approach is reserved for exploration of the sciatic nerve and for patients who cannot undergo more anterior approaches because of skin problems.)

The minimal access approach to the distal femur utilizes two windows. The lower window is derived from the lateral parapatellar approach to the knee and the upper window from the lateral approach to the femoral shaft. As in all minimal access surgical approaches, imaging during surgery is mandatory.

Femoral shaft fractures are now most commonly treated with intramedullary nails inserted using a closed technique. A minimal access approach to the proximal femur for the insertion of intramedullary nails is described.

Because the key vascular structures spiral down the thigh, passing in an anterior to posterior direction, the anatomy of the thigh is discussed in a separate section in this chapter following the descriptions of the surgical approaches. Within this section, the unique anatomic features of each approach are discussed individually.

Lateral Approach

The lateral approach is the incision used most often for gaining access to the upper third of the femur. It also can be extended inferiorly to expose virtually the whole length of the bone. Although it is an extremely quick and easy approach, it involves splitting the vastus lateralis muscle. The subsequent blood loss that results from the rupture of vessels during this procedure may make surgery awkward, but rarely is life-threatening.

The uses of the lateral approach include the following:

Open reduction and internal fixation of intertrochanteric fractures (this is by far the most common use of the approach)

Insertion of internal fixation in the treatment of subcapital fractures or slipped upper femoral epiphysis

Subtrochanteric or intertrochanteric osteotomy

Open reduction and internal fixation of femoral shaft fractures, subtrochanteric fractures, and supracondylar fractures of the femur

Extraarticular arthrodesis of the hip joint

Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis of the femur

Biopsy and treatment of bone tumors

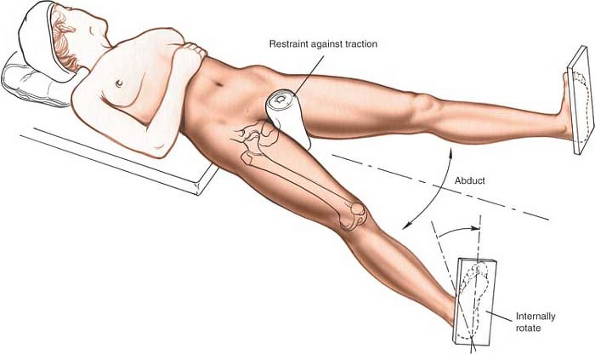

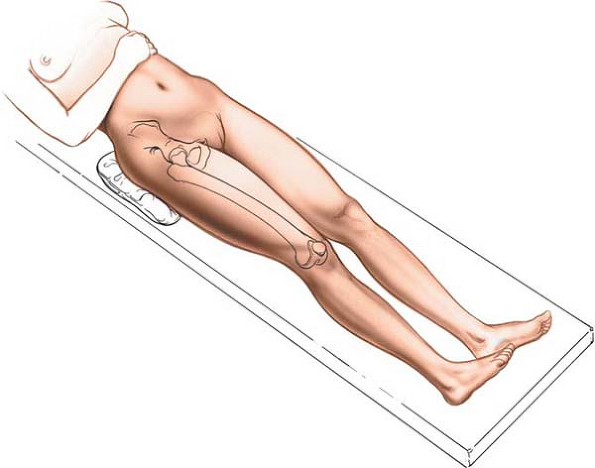

Position of the Patient

Patients with trochanteric fractures should be placed on an orthopaedic table in the supine position so that their fractures can be manipulated or controlled during surgery. Use an orthopaedic table for any procedure that involves the use of an image intensifier (Fig. 9-1). Internally rotate the leg 15° to overcome the natural anteversion of the femoral neck and to bring the lateral surface of the bone into a true lateral position.

For surgery on the shaft of the femur, use a lateral position. Place the patient on his or her side, with the affected limb uppermost. Take care to pad the bony prominences of the bottom limb to avoid pressure necrosis of the skin. Place other pillows between the two limbs to pad the medial surface of the knee and the medial malleolus of the side that is being operated on.

Landmarks and Incision

Landmarks

The posterior edge of the greater trochanter is relatively uncovered. Palpate it, moving the fingers anteriorly and proximally to identify its tip.

The shaft of the femur is palpable as a line of resistance on the lateral side of the thigh.

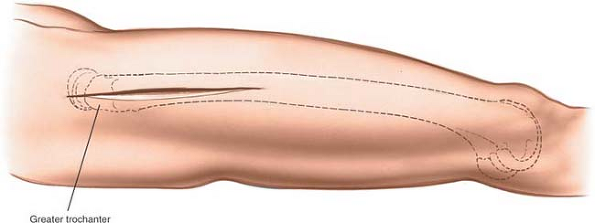

Incision

Make a longitudinal incision, beginning over the middle of the greater trochanter and extending down the lateral side of the thigh over the lateral aspect of the femur. The length and position of the incision will vary with the requirements of the surgery (Fig. 9-2).

P.465

|

Figure 9-1 Position of the patient on the operating table for the lateral approach to the proximal femur. |

Radiographic control of the length and position of the incision significantly reduces the length of the incision. Because it is accurately sited, this in turn reduces the amount of dissection and soft-tissue damage necessary for adequate exposure.

Internervous Plane

There is no internervous or intermuscular plane, because the dissection splits the vastus lateralis muscle, which is supplied by the femoral nerve. The muscle receives its nerve supply high in the thigh, however, so splitting the muscle distally does not denervate it.

|

Figure 9-2 Incision for the lateral approach to the proximal femur. |

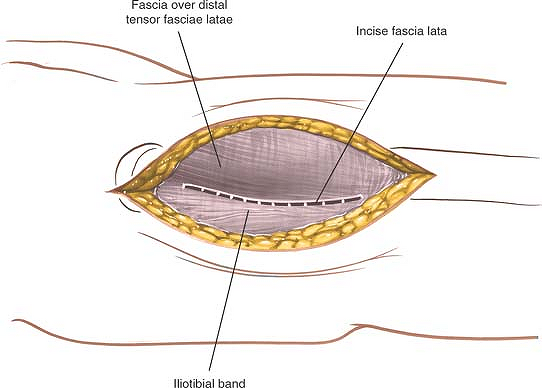

Superficial Surgical Dissection

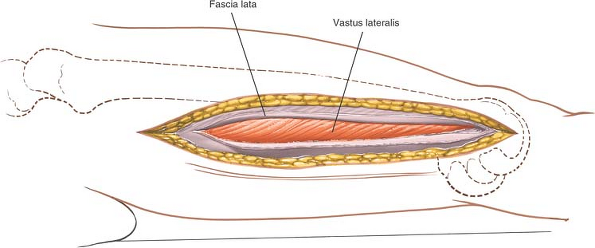

Incise the fascia lata of the thigh in line with the skin incision. At the upper end of the wound, the distal portion of the tensor fasciae latae may have to be split in line with its fibers to expose the vastus lateralis

(Fig. 9-3). This split is needed in about one third of patients, those who have tensor fasciae latae fibers extending distally beyond the greater trochanter.

P.466

(Fig. 9-3). This split is needed in about one third of patients, those who have tensor fasciae latae fibers extending distally beyond the greater trochanter.

|

Figure 9-3 Incise the fascia lata in line with the skin incision. |

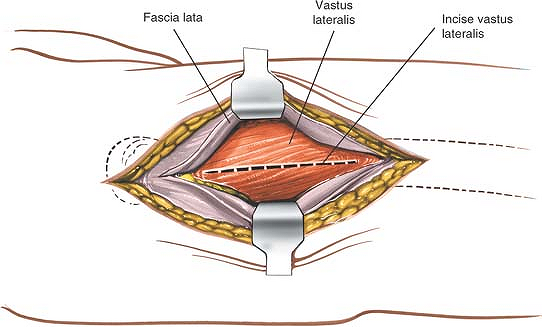

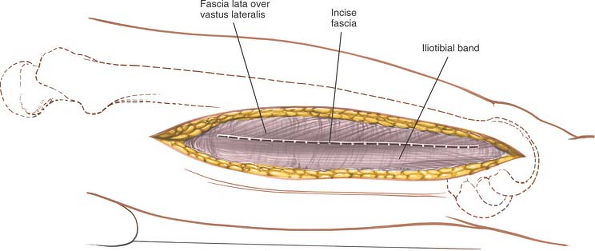

Deep Surgical Dissection

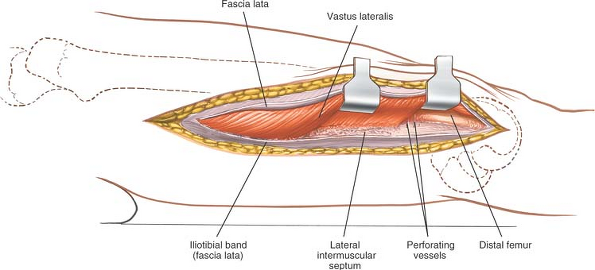

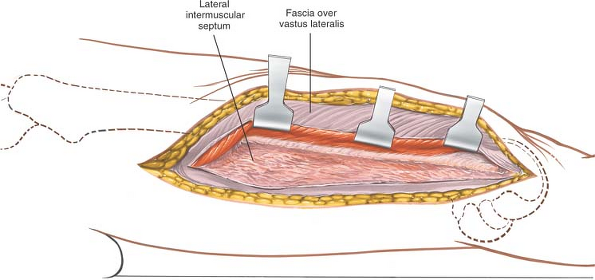

Carefully incise the fascial covering of the vastus lateralis muscle (Fig. 9-4). Insert a Homan or Bennett retractor through the muscle, running the tip of the retractor over the anterior aspect of the femoral shaft. Then, insert a second retractor through the same gap and down to the femoral shaft. Manipulate the second retractor so that it moves underneath the femur, and pull the two retractors apart to split the vastus lateralis in the line of its fibers (Fig. 9-5).

|

Figure 9-4 Incise the fascia covering the vastus lateralis. |

Continue splitting by blunt dissection. As dissection proceeds, several vessels that cross the field will be exposed. Coagulate them, if possible, before they are avulsed by the blunt dissection.

Splitting the vastus lateralis reveals the underlying lateral surface of the femur.

P.467

|

Figure 9-5 Split the fibers of the vastus lateralis. To develop a subperiosteal plane, squeeze two Homan retractors down to the femoral shaft and separate them to split the vastus lateralis further. |

Dangers

Vessels

Numerous perforating branches of the profunda femoris artery traverse the vastus lateralis muscle (see Fig. 9-36). They are damaged during the approach and should be ligated or coagulated. These arterial branches can be identified more easily if the muscle is split gently with a blunt instrument rather than cut straight through with a knife.

|

Figure 9-6 The incision may be extended distally to expose the entire shaft of the femur. |

How to Enlarge the Approach

Extensile Measures

The approach is most useful for exposing the proximal third of the bone for internal fixation of a hip fracture. It can be extended to the knee joint, however, to allow full exposure of the lateral aspect of the femoral shaft for reduction and fixation of all types of femoral fractures (Fig. 9-6; see Figs. 9-39 and 9-40).

P.468

Posterolateral Approach

The posterolateral approach1 can expose the entire length of the femur. Because it follows the lateral intermuscular septum, it does not interfere with the quadriceps muscle. Although other lateral approaches involve splitting the vastus lateralis or vastus intermedius muscles, the functional results of the posterolateral approach do not differ significantly from those of other approaches, probably because the vastus lateralis originates partly from the lateral intermuscular septum. As a result, surgery still involves detaching a part of the muscle’s origin and does not use a true intermuscular plane.

The lateral intramuscular septum lies posterior to the femoral shaft at its proximal end. This septum overlies the middle of the shaft at its distal end. The posterolateral approach is therefore ideal for exposure of the distal one third of the femur. The more proximal the approach, the greater the bulk of the vastus lateralis that will need to be retracted anteriorly and the more difficult the approach will be.

|

Figure 9-7 Position of the patient on the operating table for the posterolateral approach to the femur. |

The uses of the posterolateral approach include the following:

Open reduction and plating of femoral fractures, especially supracondylar fractures

Open intramedullary nail placement for femoral shaft fractures if facilities for closed nailing do not exist

Treatment of nonunion of femoral fractures

Femoral osteotomy (which is performed rarely in the region of the femoral shaft)

Treatment of chronic or acute osteomyelitis

Biopsy and treatment of bone tumors

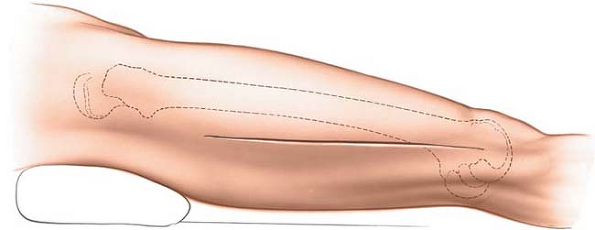

Position of the Patient

Place the patient supine on the operating table with a sandbag beneath the buttock on the affected side to

elevate the buttock and to rotate the leg internally, bringing the posterolateral surface of the thigh clear of the table (Fig. 9-7).

P.469

elevate the buttock and to rotate the leg internally, bringing the posterolateral surface of the thigh clear of the table (Fig. 9-7).

|

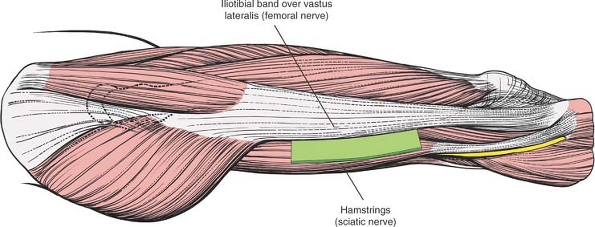

Figure 9-8 The internervous plane lies between the vastus lateralis (which is supplied by the femoral nerve) and the hamstring muscles (which are supplied by the sciatic nerve). |

Landmarks and Incision

Landmarks

Palpate the lateral femoral epicondyle on the lateral surface of the knee joint. The epicondyle actually is a flare of the condyle. Moving superiorly, note that the femur cannot be palpated above the epicondyle.

|

Figure 9-9 Incision for the posterolateral approach to the thigh. |

Incision

Make a longitudinal incision on the posterolateral aspect of the thigh. Base the distal part of the incision on the lateral femoral epicondyle and continue proximally along the posterior part of the femoral shaft. The exact length of the incision depends on the surgery to be performed (Fig. 9-9).

P.470

|

Figure 9-10 Incise the fascia of the thigh in line with its fibers and the skin incision. |

Internervous Plane

The approach exploits the plane between the vastus lateralis muscle (which is supplied by the femoral nerve) and the lateral intermuscular septum, which covers the hamstring muscles (which are supplied by the sciatic nerve; Fig. 9-8).

Superficial Surgical Dissection

Incise the deep fascia of the thigh in line with its fibers and the skin incision (Fig. 9-10).

|

Figure 9-11 Identify the vastus lateralis under the incised fascia lata. |

Deep Surgical Dissection

Identify the vastus lateralis under the fascia lata (Fig. 9-11). Follow the muscle posteriorly to the lateral intermuscular septum. Then, reflect the muscle anteriorly, dissecting between muscle and septum. Begin at the distal end of the incision where the plane is easiest to identify and develop. Numerous branches of the perforating arteries cross this septum to supply the muscle; they must be ligated or coagulated (Fig. 9-12). If the approach involves the supracondylar region, identify and ligate the numerous branches of

the superior lateral geniculate vessels, which cross the operative fields. Failure to do so will result in profuse hemorrhage, which will be difficult to control.

P.471

the superior lateral geniculate vessels, which cross the operative fields. Failure to do so will result in profuse hemorrhage, which will be difficult to control.

|

Figure 9-12 Elevate the vastus lateralis anteriorly, separating the muscle from the septum. |

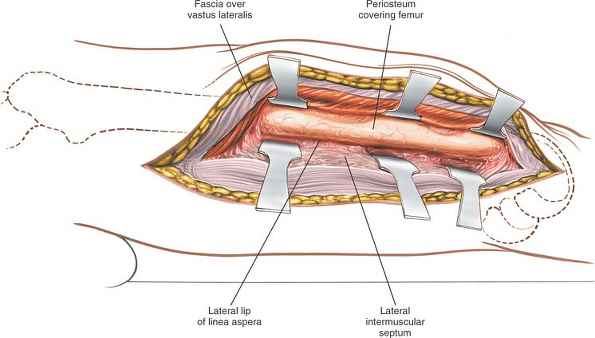

Continue the dissection, following the plane between the lateral intermuscular septum and the vastus lateralis muscle, detaching those parts of the vastus lateralis that arise from the septum until the femur is reached at the linea aspera (Fig. 9-13). Incise the periosteum longitudinally at this point and strip off the muscles that cover the femur, using subperiosteal dissection. Detaching muscles from the linea aspera itself usually has to be done by sharp dissection (Fig. 9-14).

|

Figure 9-13 Detach those portions of the vastus lateralis that arise from the septum until the femur and linea aspera are reached. Then, incise the periosteum longitudinally. |

It is very easy to open up the plane between the vastus lateralis muscle and the lateral intermuscular septum in the distal third of the femur. Moving

proximally, the muscle becomes thicker, and it becomes more difficult to lift the muscle bulk anteriorly to reveal the femoral shaft. To aid in this process, place a Homan or Bennett retractor over the anterior aspect of the femoral shaft, lifting the vastus lateralis forward. A retractor placed on the lateral intermuscular septum will help open up the gap and facilitate proximal dissection.

P.472

proximally, the muscle becomes thicker, and it becomes more difficult to lift the muscle bulk anteriorly to reveal the femoral shaft. To aid in this process, place a Homan or Bennett retractor over the anterior aspect of the femoral shaft, lifting the vastus lateralis forward. A retractor placed on the lateral intermuscular septum will help open up the gap and facilitate proximal dissection.

|

Figure 9-14 Expose the shaft of the femur. |

Dangers

Vessels

The perforating arteries (which are branches of the profunda femoris artery) pierce the lateral intermuscular septum to supply the vastus lateralis muscle. They must be ligated or coagulated one by one as the dissection progresses. If they are torn flush with the lateral intermuscular septum, they may begin to bleed out of control as they retract behind it (Fig. 9-40).

The superior lateral geniculate artery and vein cross over the lateral surface of the femur at the top of the femoral condyles. These vessels will need to be ligated for exposure to the bone.

How to Enlarge the Approach

Extensile Measures

The major value of this incision lies in its exposure of the distal two thirds of the femur. It can be extended superiorly, however, up to the greater trochanter, to expose virtually the entire femoral shaft. Note that, superiorly, the tendon of the gluteus maximus muscle lies behind the lateral intermuscular septum.

The approach can be extended easily into a lateral parapatellar approach to the knee joint. This allows accurate visualization of the entire distal end of the femur. This extension is used to allow reduction and fixation of intraarticular fractures of the distal femur.

P.473

Anteromedial Approach to the Distal Two Thirds of the Femur

The anteromedial approach provides an excellent view of the lower two thirds of the femur and the knee joint. Its uses include the following:

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the distal femur, particularly those that extend into the knee joint and require medial plating (its major use)

Open reduction and internal fixation of femoral shaft fractures

Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis

Biopsy and treatment of bone tumors

Quadricepsplasty

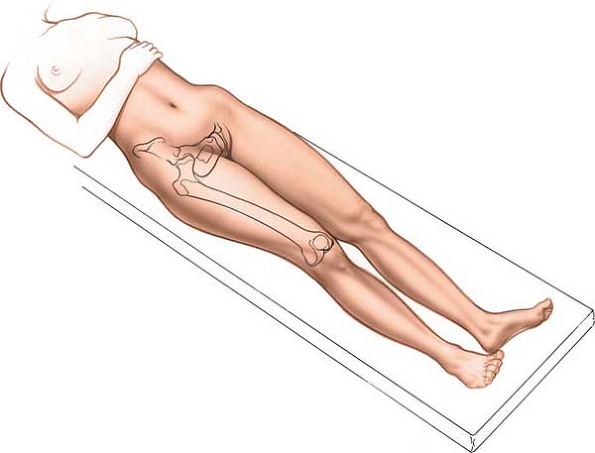

Position of the Patient

Place the patient supine on the operating table, and drape the extremity so that it can move freely (Fig. 9-15).

|

Figure 9-15 Position of the patient on the operating table for the anteromedial approach to the femur. |

Landmark and Incision

Landmark

The vastus medialis muscle is a distinct bulge superomedial to the upper pole of the patella. Only the inferior portion can be seen and palpated distinctly. The vastus medialis atrophies rapidly in many patients with knee pathology; therefore, it may be difficult to find.

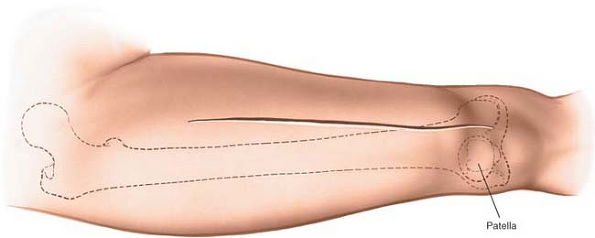

Incision

Make a 10- to 15-cm longitudinal incision on the anteromedial aspect of the thigh over the interval between the rectus femoris and vastus medialis muscles. (There are no specific landmarks for this interval other than the contour of the vastus medialis.) Extend the incision distally along the medial edge of the patella to the joint line of the knee, if the knee joint

must be opened. The exact length of the incision depends on the pathology being treated (Fig. 9-16).

P.474

must be opened. The exact length of the incision depends on the pathology being treated (Fig. 9-16).

|

Figure 9-16 Incision for the anteromedial approach to the thigh. |

Internervous Plane

There is no internervous plane; the dissection descends between the vastus medialis and rectus femoris muscles, both of which are supplied by the femoral nerve. The intermuscular plane can be used safely to expose the distal two thirds of the femur, however, because both muscles receive their nerve supplies well up in the thigh.

|

Figure 9-17 Incise the fascia lata in line with the skin incision, and identify the interval between the vastus medialis and the rectus femoris. |

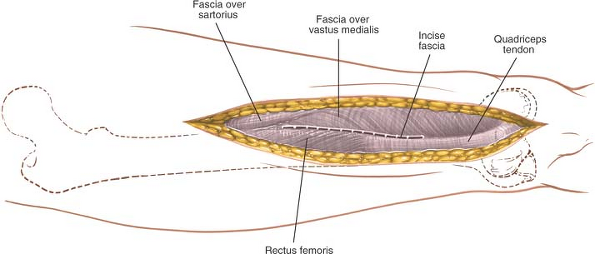

Superficial Surgical Dissection

Incise the fascia lata (deep fascia) in line with the skin incision, and identify the interval between the vastus medialis and rectus femoris muscles (Fig. 9-17). Develop this plane by retracting the rectus femoris laterally (Fig. 9-18).

P.475

|

Figure 9-18 Develop the plane between the vastus medialis and the rectus femoris, retracting the rectus femoris laterally. Begin the parapatellar incision into the joint capsule. |

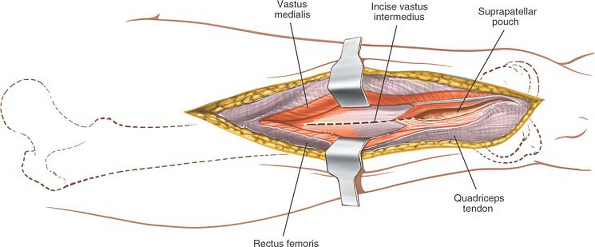

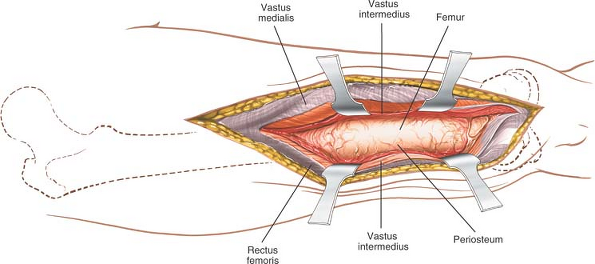

Deep Surgical Dissection

Begin distally, opening the capsule of the knee joint in line with the skin incision by cutting through the medial patellar retinaculum (see Fig. 9-18). Continue proximally, splitting the quadriceps tendon almost on its medial border. Open up the plane by sharp dissection, staying within the substance of the quadriceps tendon and leaving a small cuff of the tendon with the vastus medialis attached to it. This preserves the insertion of these fibers and allows easy closure. If the vastus medialis is stripped off the quadriceps tendon, it is very difficult to reinsert, and muscle function will be compromised. Next, continue to develop the interval between the vastus medialis and rectus femoris muscles proximally to reveal the vastus intermedius muscle. Split the vastus intermedius in line with its fibers; directly below lies the femoral shaft covered with periosteum. Continue the dissection in the epi- periosteal plane to get to the bone (Figs. 9-19 and 9-20).

|

Figure 9-19 Continue the parapatellar incision proximally, opening the joint capsule and suprapatellar region. Carry the incision into the substance of the vastus intermedius. |

P.476

|

Figure 9-20 Incise the periosteum of the femur longitudinally, and expose the distal femur by subperiosteal dissection. |

Dangers

Vessels

The medial superior genicular artery crosses the operative field just above the knee, winding around the lower end of the femur. Although it looks small, it must be ligated or coagulated to avoid hematoma formation (see Fig. 10-43).

Muscles and Ligaments

The lowest fibers of the vastus medialis muscle insert directly onto the medial border of the patella. Their main job is to stabilize the patella and prevent lateral subluxation (see Fig. 9-37). The fiber attachments of the muscle inevitably are disrupted during this approach, unless a small cuff of quadriceps tendon is taken with the muscle. Make sure to repair the incision meticulously during closure to prevent subsequent lateral subluxation of the patella.

How to Enlarge the Approach

Extensile Measures

Superior Extension. The approach can be extended along the same interval between the rectus femoris and vastus medialis muscles. To extend the deep dissection, continue to split the vastus intermedius muscle. The extension offers excellent exposure of the lower two thirds of the femur. Higher up, however, the femoral artery, vein, and nerve intrude into the dissection; the upper third of the femur is explored best by a lateral approach.

Inferior Extension. Continue the skin incision downward, and curve it laterally so that it ends just below the tibial tubercle. Incise the medial retinaculum in line with the skin incision, making the patella more mobile and subject to lateral subluxation for full exposure of the knee joint. Take care not to avulse the quadriceps tendon from its insertion during the maneuver (see Medial Parapatellar Approach in Chapter 10).

Posterior Approach

The posterior approach4 is useful in patients who cannot undergo more anterior approaches because of local skin problems. It provides access to the middle three fifths of the bone, as well as to the sciatic nerve. Although it is performed rarely, its uses include the following:

Treatment of infected cases of nonunion of the femur

Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis

Biopsy and treatment of bone tumors

Exploration of the sciatic nerve

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree