Systematically Assessing and Improving the Quality and Outcomes of Medical Rehabilitation Programs

Mark V. Johnston

Kenneth J. Ottenbacher

James E. Graham

Patricia A. Findley

Anne C. Hansen

INTRODUCTION

Demands for accountability, improved quality, and the delivery of expected outcomes have grown throughout health care. As the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) Crossing the Quality Chasm states: “The frustration levels of both clinicians and patients have probably never been higher. Health care today harms too frequently and routinely fails to deliver its potential benefits” (1). The primary motivation for quality and outcomes improvement systems in rehabilitation, however, is not the avoidance of bad care or patient injury, but the provision of high quality services that improve the function and quality of life (QOL) of persons with disabilities. Public accountability, including justification of the cost of rehabilitation, is an intrinsic part of this fundamental motivation. Medical rehabilitation facilities are caring environments, and the great majority of rehabilitation patients clearly improve in function (2). The technical basis of quality and outcomes monitoring systems for rehabilitation needs to be developed by professionals who are trained to understand the evidence basis of rehabilitation services, working with professionals experienced with clinical practice. The interests of other major stakeholders, including patient or consumer representatives, payers, and government agencies, must also be represented, even though their values may differ (3). The influence, prosperity, and even the survival of rehabilitation as a specialty may hinge on its ability to develop and implement evidence-based monitoring and management systems relevant to consumers, payers, administrators, and policy makers.

A generation ago, rehabilitation—like most of health care—was widely regarded as an applied art rather than a science. It was commonly argued that professionals could recognize quality if they saw it, but it could not be objectively predefined. The possibility of scientific measurement of outcomes was disputed. Progress has been made since then. It is now widely recognized that scientifically valid instruments are a necessary basis for monitoring the quality and outcomes of rehabilitation programs. A large number of instruments and scales are now available in rehabilitation health care, and they are widely applied in clinical and community settings. For example, inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs) use a standardized assessment protocol, the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI), which includes items from the functional independence measure (FIM) (4). Other current outcomes monitoring systems include the outcomes assessment and information set (OASIS), used in home health settings, and the minimum data set (MDS), used in nursing homes (5). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is presently developing monitoring systems that can be applied across multiple postacute rehabilitation settings, for example, the continuity assessment record and evaluation (CARE). Ensuring the validity of these instruments to evaluate the variety of needs of rehabilitation patients across postacute settings is a current challenge.

The broad thesis running through this chapter is that quality outcome monitoring and improvement efforts in medical rehabilitation must be based on the best available evidence. This evidence must be integrated with clinical experience, and interventions need to be varied and highly sensitive to individual variations in beliefs, values, and circumstances. Assertions that personal opinions alone should rule will neither advance rehabilitation as a profession nor the welfare of people with disability. While we emphasize the need to ground quality and outcomes monitoring evidence-based practice (EBP) and systematic reviews of the scientific evidence, research evidence of effectiveness is typically neither strong nor unequivocal in rehabilitation. Multiple strategies are useful for assuring and improving the quality and effectiveness of medical rehabilitation programs. Monitoring systems need to include measures of both process and outcomes.

In this chapter, we first present basic concepts and principles, necessary for rational communication about quality, outcomes, effectiveness, and evidence. We then review rehabilitation’s long experience with program evaluation (PE) and outcomes monitoring systems. Quality improvement (QI), quality assurance (QA), and Joint Commission approaches are then discussed. Because improving the quality and outcomes of rehabilitation programs will require information systems, such systems are then discussed. Other necessary approaches—including professional education, patient-centeredness, and

“clinical practice improvement” (CPI)—are then discussed. Finally, we will discuss key public issues. We hope the chapter is a useful guide and reference work for physicians, administrators, QI specialists, policy makers, and disability advocates concerned with quality and outcomes in medical rehabilitation.

“clinical practice improvement” (CPI)—are then discussed. Finally, we will discuss key public issues. We hope the chapter is a useful guide and reference work for physicians, administrators, QI specialists, policy makers, and disability advocates concerned with quality and outcomes in medical rehabilitation.

BASIC TERMS AND CONCEPTS

To discuss quality and outcomes improvement, certain basic terms and concepts need to be understood.

Evidence-Based Practice

The EBP movement has significantly influenced thinking about quality and outcomes monitoring and related benchmarks, guidelines, PE, and performance indicators. The principles of EBP were originally introduced in 1992 under the term evidenced-based medicine (6). The concepts and techniques rapidly evolved from a focus on medicine and are increasingly integrated into virtually all heath care quality monitoring and accreditation systems. Rehabilitation too needs to adopt principles of EBP. It is now increasingly recognized that measurement of functional gain itself provides only very weak evidence of program quality and effectiveness, as patients may improve even without specialized rehabilitation programming. Much stronger evidence—including evidence from well-controlled clinical trials—is required as a basis to infer provision of effective treatment.

Sackett’s classic definition of evidence-based medicine is “the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values” (EBM, 2nd ed., p. 1) (6). In this chapter, we define EBP as the use of best research evidence in clinical and community practice, both in making decisions about individuals and at the level of policy and procedures, integrating this evidence with clinical experience and clients’ values. Best evidence is no longer a matter of unfettered opinion: it is evaluated by systematic application of a predefined hierarchy of research quality. Key features of high-quality intervention studies include randomization or other methods of controlling for selection bias and case severity, blinding and avoidance of measurement biases, and minimization of attrition biases (7, 8, 9). Widely accepted standards also exist for evaluation of the quality of diagnostic, screening, and predictive (7) studies; standards also exist for measurement studies (10, 11, 12). EBP and systematic review are core to the modern view of performance improvement systems presented in this chapter. More complete information on EBP is found in Chapter 80.

Quality and Outcomes Monitoring

PE is the systematic collection and analysis of information about some or all aspects of a health service program to guide judgments or decision about that program. An effective PE involves procedures that are useful, feasible, ethical, and accurate (13). QA can be defined as all activities that contribute to defining, designing, assessing, monitoring, and improving the quality of health care. These activities can be performed as part of the accreditation of facilities, supervision of health providers, or other efforts to improve the performance of health providers and the quality of health services (14). The term quality assurance (QA) has fallen out of vogue, perhaps because it at one time led to reliance on external policing of clinicians, peer review alone, and other limited techniques. However, QA activities of some type continue to be needed to assure that standards of care are met.

Although PE and QA differ in focus, they are complimentary. PE examines programs in relation to stated objectives and is concerned with identifying and evaluating the structure, efficiency, process, effectiveness, relevance, and impact of the program. QA generally focuses on patient-specific practices of health providers and evaluates these practices with regard to standards expected by the peer group or benchmarks of exemplary practice agreed upon by the profession. In addition to program objectives and professional benchmarks, consumerfocused and outcomes-oriented performance/QIs have received increased public and professional attention.

QI involves applying appropriate methods of evaluation and outcomes assessment to close the gap between current and expected levels of quality as defined not only by professional standards but also by consumers and other stakeholders. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO) states that the most important reasons to establish an outcome-oriented assessment initiative are to (a) describe in quantitative terms, the impact of routinely delivered care on patients’ lives; (b) establish a more accurate and reliable basis for clinical decision making by clinicians and patients; and (c) evaluate the effectiveness of care and identify opportunities for improvement (15, p. 25).

Quality of care can be defined in many different ways. “Quality” is always positive connoting activities that benefit the person served in the short- or long-term. The IOM has defined quality as the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (14, 16). In other words, quality involves achieving desired health outcomes to a degree that is consistent with current knowledge of diagnosis and effective treatment.

In addition, quality care also requires treating patients with dignity and sensitivity to their individual needs, expectations, and circumstances. Communication, concern, empathy, honesty, sensitivity, and responsiveness to individual patients have long been recognized as necessary attributes of quality health care (17). Patient involvement is particularly important in rehabilitation and chronic care because engaging motivations is essential to the success of activity and behavioral therapies that work to enhance meaningful functional capacities of people served. Individuals served in rehabilitation not only want to be informed about what is going on but also want to be involved in selection of treatment goals (18).

Performance indicators. The terms “performance indicator” and “performance measure” are commonly used to designate key outcomes and processes that need to be measured and reported to judge the effectiveness and efficiency of service

delivery. The choice and implementation of performance indicators are central concerns to performance monitoring and improvement, as objective data are needed as a basis for evaluation. Performance indicators are used in QI and reported to stakeholders such as consumers, payers, governing boards, accrediting organizations, and the public. Joint Commission of Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO), National Committee for QA, and government agencies have devoted great effort to develop performance measurement systems over the last two decades.

delivery. The choice and implementation of performance indicators are central concerns to performance monitoring and improvement, as objective data are needed as a basis for evaluation. Performance indicators are used in QI and reported to stakeholders such as consumers, payers, governing boards, accrediting organizations, and the public. Joint Commission of Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO), National Committee for QA, and government agencies have devoted great effort to develop performance measurement systems over the last two decades.

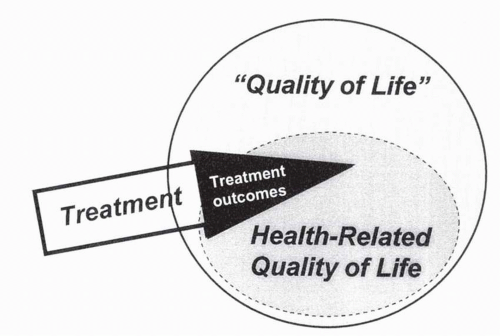

The term “outcome” is used in different ways: life outcomes, pertaining to role restoration or QOL; health-related QOL, pertaining to aspects of life, experience, or function that are logically related to physical health or recognized mental disorders; and the outcomes of care, here, rehabilitation outcomes. Rehabilitation improves many quality aspects of patients’ lives; however, it would be naïve to suggest that medical rehabilitation can routinely produce or assume responsibility for total or all encompassing improvements in patients’ lives. Although we are concerned with the person’s QOL as a whole (large circle in Fig. 12-1), medical rehabilitation is primarily directed at health-related QOL (smaller oval). Medical rehabilitation professionals are primarily responsible for those valued aspects of patients’ lives that they can affect, namely treatment outcomes (small triangle in Fig. 12-1).

The Joint Commission has defined outcomes as “restoration, improvement or maintenance of the patient’s optimal level of functioning, self-care, self-responsibility, independence and QOL” (19). The term also connotes connection to preceding rehabilitative treatments; the outcome in some sense is due to rehabilitation. It is essential to realize that outcomes due to rehabilitation are not directly measured: they are inferred from prior evidence and theory and estimated using a data set permitting adjustment for case severity and confounding factors that influence measured outcomes.

Benchmarking is basic to both quality and outcomes monitoring. A benchmark is a target value of a performance indicator. Joint Commission requires that facilities compare their processes and outcomes with those known to be attainable elsewhere (20). The Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) also writes of benchmarks. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) assumes a scoreboard of process or outcome measures (21, 22, 23, 24). Severity or risk adjustment is usually needed to develop accurate benchmarks for evaluating outcomes and processes.

Treatment Effectiveness

Knowledge of treatment effectiveness ties together processes and outcomes. Effectiveness may be defined as the sustained improvement in patient function produced by a care intervention beyond the natural healing and adjustment that occurs with less intensive or specialized care. Assertions that an intervention is effective require evidence, ideally from prior well-controlled studies. Effectiveness is assumed by use of the term “rehabilitation outcomes” and is the core professional attribute of quality medical rehabilitation. Effectiveness encompasses the appropriateness of care, the technical competence with which procedures are carried out, risks, and intended as well as unintended consequences. Both QI and outcomes monitoring systems should be based on best knowledge regarding effective treatment.

Surrogate Indicators of Effectiveness

In practice, PE and outcomes management in rehabilitation are commonly based on implicit beliefs and practical but flawed surrogate estimates of effectiveness such as functional gain. In PE, the term “effectiveness” is often used to mean how successful a program is in accomplishing its goals or the average amount of functional gain by patients. Higher rates of functional improvement may suggest greater effectiveness in some facilities than others but are far from proving it (25).

Older QI publications have defined effectiveness as “the degree to which the care is provided in the correct manner, given the current state of the art” (19, 26). In this traditional view, “correctness” is associated with adherence to normatively based standards and methods of care. Studies in acute hospitals, for instance, have provided correlational evidence that better adherence to the expert-defined best practices would improve patient outcomes (27, 28, 29, 30). By contrast, an evidence-based approach would ask about the strength of evidence for various expert recommendations, accepting expert opinion tentatively when there are no strong empirical studies.

Efficiency and Value

Efficiency means delivering appropriate, effective care within cost constraints. Straight cost considerations must be distinguished from cost-effectiveness, which involves evaluating costs of treatment against gains in patient outcomes. Measures of service use (e.g., length of stay [LOS], treatments units) are often useful surrogates for detailed computations of cost. In a managed care environment, we especially need to know whether the imposed limitations have compromised patient outcomes. In a prospective payment system (PPS) environment, if one spends too much effort on one patient, there

will be fewer resources available for others. Data are needed to guide us in determining where the optimum lies.

will be fewer resources available for others. Data are needed to guide us in determining where the optimum lies.

Rehabilitative care not only needs to be provided efficiently, but it must also be of value to its customers, including most of all patients and also payers (31). Patients, payers, and society commonly demand robust improvement in the patient’s functioning and/or QOL that endures in everyday life after discharge. QALYs—quality adjusted life years—are, in principle, applicable to rehabilitation (32, 33), but current methods of computing QOL over time have not yet been shown to be sensitive to rehabilitative interventions (e.g., functional gain) or to the decisions that rehabilitation professionals and people with disability must make (see Chapter 18).

Defining and improving the quality of care would be easy if money were not an issue. Resources, however, are always limited. The difficulty of defining affordable value is greatly complicated when available funding varies enormously across patients and no societal decision has been made regarding standards for valuation of the quality of human life over time (e.g., QALYs) (33). As economic constraints have increased and funding for rehabilitation has become more variable, assuring the provision of high-quality care has become increasingly challenging, at least in the United States.

Levels of Health and Functioning

Health and functioning are rich concepts that involve a number of levels that need to be understood given their central importance to systematic QI. Chapter 19 explains components of health outcomes as defined by the newer International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) (34). In brief, distinctions among functioning at the biological level, the level of the individual per se, and the level of the individual in society and the environment (previously designated as impairment—disability—handicap) (35) have been replaced by body systems and structure, activity, and participation. Measures of pathology—dysfunction at the cellular or biochemical level— and disease are also needed in QI and outcomes management in medical settings. The term functional limitation is also valuable to denote specific limitations or activity restriction of the person, compared to a normative average and measured in a controlled environment (36, 37).

Impairments are of focal importance in medical rehabilitation treatments. Performance monitoring systems in medical rehabilitation must at least group patients by their primary etiology or impairment group, and ideally, severity adjustment is in terms of the primary diagnosis or impairment (e.g., severity and level of paralysis in spinal cord injury) (38). If an impairment is used as an outcome measure, there should be evidence—not merely an assumption—that the impairment is significantly related to functional outcomes or QOL. Numerous medical and nursing conditions treated in medical rehabilitation—infection control, reduction of decubitus ulcers, control of blood pressure, prevention and treatment of deep vein thrombosis, diabetes management, pain relief—meet this criterion. In many circumstances in rehabilitation, however, a pathology or impairment can be treated and reduced without alteration of the primary disease or the functional status of the patient (39). Range of motion and even spasticity reduction, for instance, are poorly correlated with functional outcomes (40), probably because they are not the primary barriers to improved function for many patients. Discriminating more worthwhile from less worthwhile but still technically effective interventions is a challenge for rehabilitation providers.

Medical rehabilitation deals with all these levels but has long focused on diminishing impairment and improving basic capabilities of persons with disabilities (e.g., reducing assistance requirements in activities of daily living [ADL]). There are currently a number of reasonably reliable and valid scales of functioning that have been developed for various rehabilitation settings (5, 41). The FIM, for instance, has been widely studied, and its utility and basic validity for assessment of physical functioning are well established, as are its limitations in the areas of speech, language, and cognition (42). In assessing function, it can be important to realize that activities and disabilities are determined not only by impairments but also by the extent of compensating strengths. Moreover, disability and even indicators of participation may have a loose connection to life satisfaction (38, 43).

Health Status Measures

Medical rehabilitation outcome measures may be considered to be a subcategory of health status and QOL measures. Books summarizing different scales of health-related QOL are now available (38, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48). These sources are filled with scales relevant to rehabilitation outcomes assessment, though their sensitivity and logical applicability to medical rehabilitation require verification. Perhaps the most commonly used measure of general health is the short form 36 (SF-36) (49), although many other measures are also used (48). Some of the subscales within these instruments appear to be too broad or are otherwise not directed at problems treated in medical rehabilitation, but many dimensions—such as pain relief, general feelings of health and well-being, and physical function—are relevant.

QOL measures are relevant to rehabilitation outcomes assessment. Subjective or affective QOL is so important that it deserves assessment, despite its (nonqualified) exclusion from the World Health Organization (WHO) scheme. Subjective well-being and life satisfaction have been increasingly studied for use as ultimate rehabilitation outcomes measures (50). Subjective well-being is statistically associated with health and function, community participation, and a loving and satisfying social life, but the inconsistency of these associations demonstrates that subjective well-being cannot be reduced to indicators of objective health and circumstance (43, 50): the person’s own expectations or implicit standards regarding his or her own life are critical. Chapter 12 discusses QOL assessment in greater detail. At this point, indices of patient well-being are sufficiently well validated to be used in research but have not yet been validated for use as routine indicators of the performance of individual rehabilitation programs.

Criteria for Choice of Measures

Criteria for choice of measures for performance and outcomes monitoring systems include relevance of content, reliability, other internal psychometric characteristics, or alternatively, biometric validity, and evidence of predictive validity, including evidence of utility in practice (10, 13, 51, 52, 53). While ease of administration and expense are critical considerations in practice, justifiable expense depends on the benefits of the measurement system.

Standards and Levels of Validity and Reliability

Scales employed in performance monitoring should meet recognized standards of reliability and validity in rehabilitation or other fields (10). While reliability and validity are commonly treated as catch phrases, they in fact subsume a set of interrelated criteria for the quality and utility of measurement. The validity of functional and QOL measures can be understood as a set of criteria for (a) sensible internal structure—that is, whether the set of items or procedures has the needed content, low intrinsic error, desirable internal psychometric characteristics and (b) desired external validity characteristics, including whether it generally “behaves” as it should according to one’s understanding of the construct, including convergent and divergent validity, and evidence of utility in practice, also known as consequential validity—that is, whether the measure leads to correct inferences and verifiable benefits, at least in its major application or use (52, 54). If the construct to be measured and the main application are clearly specified, it is possible to grade the quality of measurement evidence (52, 54, 55).

One needs to know the reliability—that is, the stability, agreement, and reproducibility—of measures to interpret them. Without reliability information, one may not be able to distinguish between actual objective differences in scores and mere subjective or chance fluctuations. Error-prone indices of the appropriateness of medical care have been shown to overstate the frequency of inappropriate care (56).

Validity is a concept associated both with the construct being measured and with its application. Evaluation of a measurement procedure involves consideration of whether it has necessary internal characteristics (e.g., homogeneity, hierarchical structure) as well as external predictive characteristics, including validity for some purpose or construct. Accuracy is the relevant criterion to evaluate the validity of a measure when a true “gold standard” is available. Sensitivity is the probability of detecting a condition that a person actually has. Specificity is the probability that the test gives a negative result among people without the condition. When the question concerns whether an individual actually has a specified condition, given a positive result of a test, the needed statistic is positive predictive validity, which requires also knowledge of base rates (57, 58).

When summing items to provide a meaningful summary number, one should know the degree to which the items are internally consistent, that is, additive and unidimensional (58, 59, 60). The FIM instrument, for instance, consists of at least two dimensions: motor ADLs and cognitive-psychosocial function (61).

Limited range of item difficulty has also been a problem with some scales used in rehabilitation, since rehabilitation deals with a great range of human performance—from coma or total paralysis through independent living and paid employment. Many existing scales are sensitive to the typical range of improvement seen in medical rehabilitation hospitals (37, 42, 62, 63) but still have ceiling or floor problems, that is, they may be insensitive to very real improvements that occur in some patients who remain at a “total assist” level in ADLs or in individuals who are independent in ADLs but need speed, endurance, or higher level skills to sustain a productive lifestyle in the community (64).

To employ parametric analysis techniques (e.g., reporting means, t-tests, or Pearson correlations), the scales employed should have equal-interval characteristics. Measures developed using Rasch analysis have probabilistic equal-interval properties (58, 59, 60, 65). They can identify and lessen floor and ceiling limitations of older measures, as can other forms of item response theory (IRT) (58, 60). The method also has the advantage of identifying “misfitting” persons, that is, individuals whose pattern of functioning is so atypical that the conventional method of scoring their outcomes may be misleading. Different methods of scoring functional scales may be needed for different diagnostic groups. Walking, for instance, is relatively easy for a person with brain injury but is near impossible for a person with complete paraplegia; its significance as a marker of progress is radically different between the two persons. Chapter 11 presents additional criteria for choice of measures.

Sensitivity to Change and Evidence Bases

Sensitivity to change is a basic criterion for choice of outcome measures. This is true in the sense that outcome or performance measures unrelated to actual treatment objectives and valued outcomes should not be employed. At the same time, a measure can be too sensitive, so that improvement is of little value to patients or can fluctuate due to factors unrelated to treatment. With modern IRT and other metric analysis, it is possible to quantify the degree of sensitivity of a measure, that is, the degree of error of measurement. Previous controlled research provides a superior basis for choice of outcome measures; as such, research can identify attainable outcomes and linkages between outcome and needed treatment processes.

Severity Adjustment and Statistical Consideration

The need for severity or risk adjustment of performance data can hardly be overemphasized. QI and outcomes monitoring systems that are unadjusted or poorly adjusted for disease severity, functional limitations, and other factors that affect outcomes are likely to provide misleading reports. While all factors cannot be controlled statistically, outstanding confounding factors can be measured and their effect projected. Finally, knowledge of at least basic statistical principles is needed to interpret performance monitoring data. Sample size is always a consideration: a single bad outcome may well be a fluke; a pattern of outcomes below severity-adjusted norms indicates a possible process problem needing further investigation.

PROGRAM EVALUATION AND OUTCOMES MANAGEMENT

This section discusses systems of measurement, monitoring, and interpretation focused on the outcomes attained after care. We begin by discussing PE and associated schema in rehabilitation. Rehabilitation facilities—largely under the aegis of the CARF—now have several decades of experience with PE, and the resulting knowledge provides a basis for current program monitoring and clinical management activities.

Rehabilitation is provided in many settings, including transitional care facilities, nursing homes, outpatient clinics, homes, and hospital-based IRFs. Most of our examples will deal with IRFs and the most common outcome measure currently employed in IRFs—the FIM—in order to provide a focus and to limit length. Principles and concepts apply to other settings in which health-related rehabilitation is provided.

Program Evaluation

PE refers to a variety of information-gathering activities designed to aid in program development or functioning (i.e., formative evaluation) or to decide whether a program, as a whole, is worthwhile (i.e., summative evaluation). Many approaches to PE have been employed over the last three decades (66). “Performance monitoring” is a more current term that includes both PE and monitoring of key processes. Accountability to the public and internal management are overarching purposes regardless of rubric. These systems have multiple uses, including marketing, profitability, program planning and development, research, prognosis, utilization review, and improved clinical planning and treatment.

CARF and the Program Evaluation

Leaders in rehabilitation have long realized that the field needs to demonstrate its benefits to the public. Beginning in the 1970s, CARF assumed leadership, providing a forum that led to standards that required established rehabilitation facilities to develop PE systems that measure outcomes (67), implemented in numerous rehabilitation facilities over past decades.

PE has been described as “a systematic procedure for determining the effectiveness and efficiency with which results are achieved by persons served following services” (18). These results are collected on a “regular or continuous basis” for all patients or for a systematic sample of patients (18, 68). PE and outcomes management involve setting goals and expectancies. If goals are not attained, reasons should be determined and action should be taken. In its usual form, PE does not provide answers to specific problem areas but merely identifies that a problem or strength exists. Answers are identified through more in-depth investigations involving further analyses of data, chart review, examination of quality measures or monitors, and discussions with the knowledgeable staff (18, 21, 69, 70, 71, 72). PE systems are used to help make clinical management decisions and improve program operations.

Realizing the need for objective comparative data, most medical rehabilitation programs have joined large data systems. Accreditation standards state that organizations should compare their results and/or processes to some benchmarks, such as pooled data systems, the organization’s own larger network, and/or the published literature.

CARF has long emphasized meaningful, sustained outcomes in the real world after discharge. The goal is to maximize patient functioning and QOL in the community after discharge. Medical outcomes are noted when these may affect functional or general health outcomes. CARF standards ask that rehabilitation programs assess outcomes in terms of the WHO’s ICF (34) and emphasize the patient’s goals, desired activities, community participation, and satisfaction with services (18).

Experience with PE systems resulted in a shift of emphasis away from choice of measures and formal design of the PE system, and as early as the 1980s, use of the PE—not details of system design—became the key point. In the mid-1990s, CARF standards changed to use the terms “outcomes measurement and management” rather “PE” in order to emphasize the need for more operationally oriented approaches.

The Standard Rehabilitation Program Evaluation Model

In the 1970s and 1980s, medical rehabilitation programs developed their own tradition in PE (68). These PE systems were designed to provide an overview of program outcomes. In effect, they were designed to assure outcomes to the public, that is, to be summative evaluation systems. In operation, however, these systems functioned as formative evaluation systems (70). Information on outcomes is given primarily to program staff, who constitute the main audience for reports. Improved program management was, in fact, a primary expectation, leading to the relabeling as “outcomes management.”

Standard PE systems in rehabilitation have three components: design, goals and objectives, and reports. While this basic model is still widely used, updating has occurred as part of CARF’s strategic outcomes initiative to incorporate notions of outcomes management. CARF offers training, guidance, and materials on outcomes management. Anyone developing, implementing, or using a PE or QI system in rehabilitation should consult a CARF standards manual or Web site (www.carf.org) for references to the most recent information (18). Major components of a standard PE system are summarized below.

Program Purpose and Description

The PE design is based on a mission statement describing who the organization serves, what services it provides, and what goals it expects to accomplish. Goals should be anchored in the concerns of the persons served and other stakeholders—groups or entities with an interest in the success of the program. The special programs that constitute the organization are then described (e.g., stroke program, brain injury, spinal injury, pain program, general rehabilitation, independent

living center). Key influencers are listed to ground the statement in reality. These are external agencies that constrain and direct the rehabilitation program, such as the rehabilitation market and clients, referral sources, patients, staff, Medicare, third-party payers, and key government agencies.

living center). Key influencers are listed to ground the statement in reality. These are external agencies that constrain and direct the rehabilitation program, such as the rehabilitation market and clients, referral sources, patients, staff, Medicare, third-party payers, and key government agencies.

Each program within an organization and the population it serves are to be described:

General program objectives. Defining a PE system requires defining program objectives. Foremost among these are anticipated results to the primary clients, but indicators of efficiency are also typically needed.

Admission criteria or definition of the population served in the program. Both inclusionary (e.g., cerebrovascular accident) and exclusionary (e.g., free from communicable disease, over 18 years of age, noncomatose, dependent in ADLs and ambulation, medically stable for 3 hours per day of therapy, likely to survive at least 6 months) criteria are defined.

Persons served, described with regard to diagnosis, functional issues and problems to be addressed, and relevant demographics.

Services provided or readily available to the patient, such as medical care (e.g., physiatry), physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech/language pathology, psychology, social services, nursing, or attendant care.

General Program Objectives

CARF standards require the measurement of program performance in the domains of effectiveness (results or outcomes for persons served), efficiency (relationship between outcomes and resources used), service access (e.g., number of days from referral to admission, convenience of the hours and location of operation), and satisfaction (experience of the persons served and other stakeholders) (18). Effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction have been in the CARF standards for at least three decades, with service access being added to reflect the challenging and dynamic aspects of today’s health care environment. Data elements to assess these domains are measured at admission, discharge, and follow-up, depending on the appropriate time for each data element. Outcomes are assessed after discharge. Follow-up data collection usually takes place 3 months after discharge but other periods can also be justified.

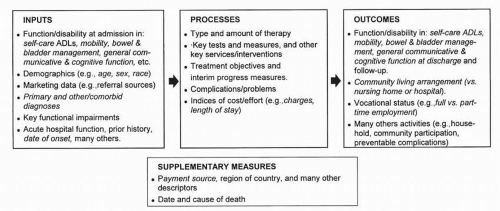

FIGURE 12-2. Basic conventional PE framework for rehabilitation programs. Items from the IRF-PAI are shown in italics. |

Also needed are progress objectives or intermediate outcomes in terms of patient improvement in the clinical setting toward outcomes such as improved independence in mobility, self-care, communication, or medical self-management. These are similar to (but less specific than) our concept of treatment objectives.

Efficiency objectives are also needed. Resources consumed such as staff time, LOS, number of treatment sessions, and dollars should be monitored and related to the results achieved. For example, the functional gain for a given LOS can be monitored to ensure that outcome is not sacrificed with resource restriction.

Program Evaluation and Outcomes Monitoring Systems in Rehabilitation

For several decades, rehabilitation programs have employed a model of PE. This model is only one of several alternatives; textbooks provide lessons in the variety of approaches and issues encountered in PE more generally (66, 73). We describe this standard or classic model because examples of it are comparatively well-defined and tested and because lessons from it provide the basis for current and future performance monitoring systems.

Typical constituents of a rehabilitation inpatient hospital PE system are shown in Figure 12-2. The sparseness of measures (italicized) in the process box and the larger set of admission (i.e., input) and outcomes (i.e., discharge and follow-up) measures show the emphasis of conventional PE systems. Scales of independence in ADLs such as the FIM constitute the primary input (e.g., admission, baseline) and output (e.g., discharge, follow-up) measures. Cost and LOS are classified here as process or input measures because they indicate the degree of effort or resource use devoted to benefiting the patient. PE systems also address quality of routine nursing care, hotel services, and patient satisfaction (74, 75).

The FIM instrument is the most commonly used functional outcomes measure in inpatient medical rehabilitation. It is an 18-item scale that rates each item on a scale ranging from 1 (total assist) to 7 (completely independent). The FIM consists of two overall factors (motor function and cognition) and recent reports indicate acceptable-to-good reliability (65). It became the basis for the PPS for medical rehabilitation hospitals in the United States beginning January 1, 2002.

The most widely used set of rehabilitation performance indicators at present is found in the IRF-PAI data set. This data set contains information on impairment group, FIM at admission and discharge, demographic information, and LOS. General purpose data sets categorize patients so that they can be grouped by estimate expense for the PPS. For purposes of PE or clinical performance monitoring, however, the information system needs to be tailored to diagnostic and functional groups.

PE systems also need supplementary measures used for general descriptive or comparative purposes (see Fig. 12-2). Demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, race) are needed as input or independent variables. Although they typically are not good measures of case severity, demographic variables do help segment the population for other analyses (e.g., access to care, service type).

Data on and reasons for rehospitalization and death are also essential supplementary measures in PE in medical rehabilitation, which treats aged, infirmed, and chronically ill patients. Although the main purpose of medical rehabilitation is not to decrease mortality, certain medical rehabilitation programs have been shown to substantially increase survival (76).

Even though accreditation standards have allowed completely local measures and standards, the flimsiness of completely local, subjective expectancies has been recognized. Acknowledging this, rehabilitation programs have voluntarily created regional and national outcomes data systems such as the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, eRehab-Data, ITHealthTrack, and other firms. The use of normative benchmarks is highly valuable to performance monitoring but provides a challenge when the available benchmark data do not correspond exactly to the program’s objectives or population.

Needed Specification and Additional Design Points

Defining a useful PE system requires forethought, including

Specification of whom measures are applied to. While traditional program objectives were applied to all patients in the program, newer approaches recognize that important and expected outcomes vary across groups. CARF standards after 1998 require analysis of outcomes in meaningful groupings rather than in all patients.

Specification of how measures are implemented and when they are applied. Most programs measure function at admission and discharge. Assessment of function 1 to 6 months after discharge gives a more valuable picture of patient outcomes. Follow-up of outcomes has become common and is required by CARF standards. The person who does the measurement should also be specified.

Specification of expectancies—specific statements of the expected level or range for objective performance indicators. The classic PE model involves specifying a range of performance expectancies: minimal, optimal, and the maximal, thought to be attainable under ideal circumstances. Outcomes were not to fall below the minimum. If they did, action was to be taken (67, 68). Expectancies are commonly based on a combination of internal trends and targets, and if known, regional or national norms.

Consideration of the relative importance of objectives. In the traditional PE model, program success was to be summarized in a single number. Actual objectives attained were multiplied by weights and expectancies chosen so that optimal attainment of outcome was signified by 100. The weighting system is no longer required, but the concept of weighting outcomes can still be useful.

Additional points for design of outcomes monitoring systems are as follows:

Cases that stay only a few days are not comparable to fullstay cases and need to be looked at as a separate group. Long-stay outliers also need to be examined.

Outcomes monitoring systems center on episodes of illness rather than on administratively convenient units such as a stay in rehabilitation. Readmissions need to be collapsed or analyzed separately. Efficiency cannot be achieved by cycling difficult cases back and forth between facilities.

Some rehabilitation programs distinguish between cases admitted for different reasons. Some patients, for instance, are admitted largely for care of certain medical-nursing problems that rehabilitation hospitals are particularly adept at treating (e.g., decubitus ulcers, urinary tract infections, weaning a patient from a ventilator). Incorporating measures relevant to the reasons for admission and for rehabilitative treatment enhances the meaningfulness of outcomes monitoring reports.

Outcome Monitoring Models for Different Populations

Patient populations need to be divided into major groups, usually by etiology or impairment group and functional severity. References are available on how to tailor a PE system for

Because inpatient rehabilitation programs must contend with numerous mixed-diagnosis cases, comorbidities, and rare diagnoses, mixed-diagnosis evaluation systems are a necessity if outcomes (and processes) are to be monitored for all patients. Functional improvement is a meaningful, if imperfect, way of quantifying the

benefits in mixed-diagnosis groups. Mixed-diagnosis systems that focus on functional and participation-level outcomes appear to be relatively successful for later stages of rehabilitation, including transitional living, community integration, vocational rehabilitation, and long-term nursing home care. Both function and diagnosis are critical in evaluation of processes and outcomes of inpatient, outpatient, and at-home medical rehabilitation programs.

benefits in mixed-diagnosis groups. Mixed-diagnosis systems that focus on functional and participation-level outcomes appear to be relatively successful for later stages of rehabilitation, including transitional living, community integration, vocational rehabilitation, and long-term nursing home care. Both function and diagnosis are critical in evaluation of processes and outcomes of inpatient, outpatient, and at-home medical rehabilitation programs.

Outcomes Measurement

This section examines issues distinctive to the measurement of outcomes for rehabilitation PE.

Generality of Measures

PE goals have been designed to credit the program with the larger benefits it produces, such as independence from assistance (68). These goals are more general than treatment or case management objectives. Measures of long-term outcomes in the community are valuable for marketing and are ultimately needed for policy and accountability (69, 70). Data on how a program has reduced the frequency with which patients are institutionalized in nursing homes and hospitals after discharge, for instance, are meaningful and even influential with boards of directors, government officials, insurers, families, and referral sources. While reports of such benefits are useful in communication of the benefits of rehabilitation to the public, more proximal outcome measures are usually more closely related to interventions and hence are more likely to be related to action to improve clinical processes.

Performance Versus Ability

The standard and usual practice is that primary outcomes are measured in terms of actual patient performance, preferably measured in the community after discharge, rather than in terms of capability demonstrated or judged in the clinic (63, 68, 84). This is because actual performance is usually a more reliable and objective measure than judged ability, and activities in the community are more meaningful and valued than activities in the clinic. Abilities that are used in practice prima facie provide greater benefit than those used in artificial situations. Exceptions exist when dealing with performance capabilities that are important though infrequently needed (e.g., safety skills) or if there is evidence that the clinical performance has high validity as a proxy for real-world outcomes.

Timing of Outcomes Measurement: Follow-up

Outcomes for persons served are best measured following discharge (68). Measurement at discharge is less expensive but may be less informative, as clinical staff are already aware of patient function at discharge. Information on durability of outcomes is valuable. Patterns of under-preparation, or of long stays by patients otherwise ready for discharge, should be actionable. Whatever time is chosen, data need to be obtained from all persons served or from a representative sampling (18).

There is no perfect time for follow-up, as there are contrasting advantages to both short-term and long-term follow-up. Three months has been the most common period for follow-up of rehabilitation outcomes, but periods of 1 to 6 months after discharge are also found. Rehabilitation involves enhancing healing and adaptation processes, so recovery processes should ideally be measured repeatedly over time.

Outcomes after discharge are usually assessed by telephone calls or clinic visits. PE systems in rehabilitation have long employed telephone follow-up. A great deal of research has shown that telephone follow-up using structured questionnaires of demonstrated reliability and validity (10) provides a good balance of reliability, low rate of missing data, and modest-to-moderate costs. The number of self-report scales for assessing health and function with basic knowledge of reliability and validity is now large (37, 42, 44, 45, 46, 47, 62, 85, 86). In-clinic follow-up methods are required to objectively assess medical problems. Missing data, however, can be a problem if patients do not return for their follow-up visit in the clinic. Tele-rehabilitation technologies may improve our capacity to provide objective patient assessment following inpatient discharge.

Practical difficulties of follow-up include its expense, funding restrictions on continuing outpatient care, a lack of payment for educational or evaluative follow-up, and the fact that continuing outpatient care may involve a different provider than inpatient care. Nonetheless, rehabilitation programs can be improved by ongoing knowledge of whether new, unexpected problems or complications arise after discharge, and if so, to whom and why. Monitoring of long-term outcomes is also needed to assess whether changes in health care designed to control costs have compromised the health or functioning of patients undergoing rehabilitation.

Benchmarking Functional Outcomes

The availability of benchmarks or standards of comparison is basic to systematic QA and QI. While they may be obtained from many sources, including the published literature, contemporary benchmarks are most commonly obtained from shared data systems that pool data from a number of facilities. The typical outcomes benchmark in rehabilitation has been average functional outcome or gain for major diagnostic groups. Accurate adjustment for case mix and severity is essential for meaningful comparison of raw quality and outcome indicators across patient groups and programs.

Severity Adjustment for Functional Outcomes

To compare a program’s outcome or improvement scores to a benchmark, one should examine major factors that drive these scores. There are a number of factors that generically affect functional outcomes across many diagnostic groups in rehabilitation (25, 37, 60, 87):

Functional severity at admission. Improvement may not be equally likely or meaningful across all levels of an admission measure. Some studies have reported curvilinear relationships, that is, greater improvement among patients admitted at intermediate levels of severity (25, 87).

Chronicity (i.e., onset-admission interval). After the acute phase of many severe injuries, there is a period of relatively rapid recovery, followed by increasingly slow improvement and eventual asymptote, at least on a group basis. Control for natural history recovery curves is needed.

LOS. Improvement in rehabilitation tends to be correlated with LOS.

Differences in comorbidities and severity of illness or injury (38). Differences in improvement across facilities may be due to differences in medical-nursing severity or case mix. Diagnostic complexity and comorbid conditions adversely affect outcomes and increase LOS in rehabilitation (88). Further development of indices and models of such factors is needed to identify patients with high medical-nursing needs and to establish clinically useful performance benchmarks for them.

Longitudinal research has identified relatively powerful outcome predictors within diagnostic groups. General severity of disease or impairment is typically a major predictor (e.g., severity of spinal paralysis and American Spinal Cord Injury Association [ASIS] motor scores in spinal cord injury [SCI] (38), Glasgow Coma Scale and duration of unconsciousness or posttraumatic amnesia for traumatic brain injury [TBI] (42), severity of paralysis as measured by Fugl-Meyer Motor Scores in stroke (89)). Premorbid factors can be powerful predictors of long-term community outcomes after rehabilitation, even more powerful than severity of injury (90). A great deal of research has been done on predictors of outcome following rehabilitation, and this research is applicable to quality outcomes improvement.

There are several methods of case mix or severity adjustment for medical rehabilitation (91). As methods of risk or severity adjustment, all these are approximate and typically predict a minority of the variance of LOS or functional gain. Rankings of acute hospital outcomes are sensitive to the method of adjustment employed (92). One would expect similar results for rankings of rehabilitation hospitals by functional gain.

Function-Related and Diagnostic Groups for Prospective Payment

Function-related groups (FRGs based on the FIM) were developed to adjust inpatient medical rehabilitation caseload for case-mix factors affecting LOS (93). Relabeled case-mix groups (CMGs) are now used as a basis for the Medicare’s PPS for patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation programs in the United States. CMGs group patients based primarily upon admissions FIM and impairment group. Average LOS can be projected. FIM-FRGs predict about 31% of the variance of LOS in rehabilitation, which is similar to the performance of diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) for acute hospital LOS. FRGs and CMGs are more detailed than previous PE systems that reported by broad etiologies. Strokes, for instance, were grouped into multiple diagnostic-functional subgroups (94). FRGs classify rehabilitation patients into groups that are more clinically homogeneous and interpretable than groupings by primary diagnosis alone. FIM-FRGs have been used to investigate the “efficiency” of rehabilitation, that is, the relationship of functional gain to cost or LOS (95).

The main use of FRGs/CMGs is as case-mix adjusters to identify groups whose costs are higher or lower than expected. They are used to identify patients whose LOS exceeds the average for the FRG. They are, however, potentially applicable to analysis of efficiency and QI in rehabilitation, defining patient groups whose gains in function are unexpectedly low given LOS (94, 95).

Functional Gain as an Indicator of Quality

It was once thought that functional gain would provide a robust indicator of the quality of rehabilitation programs. While greater gain in function is undoubtedly desirable, research connecting functional gain of actual ongoing rehabilitation programs to indicators of care processes or program characteristics is scarce. Recent, relatively large studies have failed to find an appreciable correlation between staffing intensity and other characteristics of inpatient rehabilitation programs and severity-adjusted functional gain (87). Functional outcomes and LOS, however, are relatively predictable, and managed care clearly constrained LOS in rehabilitation hospitals. “Relationships between rehabilitation practices and functional gains by patients do not appear to be either simple or overt” (87). With continued research, one may expect that reliable connections will be identified between characteristics of certain kinds of rehabilitation programming and certain severity-adjusted outcomes for selected patient groups.

Measurement and Statistics: Summary

Medical rehabilitation has reached agreement on basic typical domains for inpatient programs (e.g., mobility and self-care ADLs in the FIM), but measures of other critical domains still have to be developed or agreed upon (e.g., measures of treatment objectives clearly linked to therapies prescribed, extended or instrumental ADLs, ecologically valid measures of communicative and cognitive outcomes, patient satisfaction, and family and other environmental factors) (10, 38

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree