Physical Activity for People with Disabilities

James H. Rimmer

Jennifer A. Gray-Stanley

Several studies have reported that people with disabilities are more likely to be sedentary (1,2), have health problems (3), and experience substantially more barriers to physical activity participation compared to the general population (4, 5, 6). This increases the likelihood that, as they age, they will have greater difficulty maintaining their ability to work, participating in recreational activities, performing self-care activities (7,8), and engaging in various activities in their community (9). The subsequent physical limitations that many people with disabilities experience may not be entirely associated with the primary effects of the disability, and some or much of the limitations may be related to the effects of disuse and deconditioning (10,11).

Improving health and function in people with disabilities has the potential to facilitate greater levels of participation in all aspects of society, including work, leisure, and recreation; reduce or mitigate secondary conditions (12); and achieve a higher satisfaction with life (13). An important first step in this process is for clinicians and health professionals to find effective ways to identify and remove the many barriers to participation that people with disabilities encounter when attempting to become physically active or increase their current levels of physical activity.

The focus of this chapter is to guide health care professionals in their efforts to increase physical activity in patients or clients with disabilities. The first section discusses how community-based physical activity programs can be used as a mechanism for transitioning patients/clients from rehabilitation to self-maintenance of health and function across the life span. Within this section is a discussion of an approach to promote physical activity in people with disabilities, which includes tailoring physical activity for a patient/client and a model for systematically prescribing physical activity for individuals with physical disabilities. The second section focuses on specific types of recreation, fitness, and sports activities that individuals with disabilities can engage in and identifies appropriate community-based resources.

TRANSITIONING FROM REHABILITATION TO COMMUNITY-BASED PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

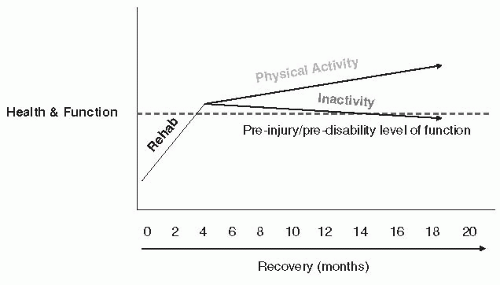

While most individuals who are recovering from a serious injury or accident will receive a certain amount of rehabilitation, the gains in health and function are often lost after the person returns home if he/she does not continue some type of home- or community-based physical activity program (14,15). Most rehabilitation is limited to the subacute period and is designed to restore or improve the most critical functional skills needed to assist the person in performing BADL (basic activities of daily living) and/or IADL (instrumental activities of daily living) (15). Once the person returns home, much of the responsibility for continuing to perform the recommended rehabilitative exercises is left to the individual and/or his or her caregiver. Figure 54-1 provides a conceptual illustration of what often occurs after an injury, accident, or onset of a new health condition that leads to a progressive decline in health and function. Typically, an individual receives a few to several days of rehabilitation in a hospital setting or outpatient facility, though this varies according to the injury. Individuals with more severe disabilities (i.e., spinal cord injury) receive longer hospital stays. Significant progress is often made as a result of intensive rehabilitation and the natural phase of recovery. But after the person returns home to what is often a considerable alteration in health, function, and lifestyle, there is, theoretically, a gradual decline in health and function resulting from physical inactivity. A primary goal of every rehabilitation program should be to increase physical activity postrehab to avoid a state of severe deconditioning that could impose serious limitations in performing BADL and IADL. In some ways, the key to a successful rehabilitation program is identifying effective strategies that can support individuals in participating in some form of regular physical activity after they are no longer receiving therapy. People with disabilities who reported a higher level of physical activity also indicated a higher level of community reintegration compared to participants who described their physical activity as low or inactive (16,17).

Tailoring Physical Activity to Meet the Unique Needs of the Patient/Client

Tailoring physical activity programs that recognize the unique circumstances surrounding each individual is an important aspect of prescribing physical activity programs that have a greater likelihood of successful initiation and adherence (18). Research on physical activity indicates that generic programs not targeted to the needs of any particular end user are far less likely to result in long-term maintenance of health-promoting behaviors (19,20). By assessing a combination of factors,

including the person’s motivational level (readiness to change), physical activity profile, health and mobility limitations, and barriers to participation, a program can be developed that meets each person’s specific needs, interests, and circumstances. Thus, physical activity recommendations for people with disabilities may be more effective if they are individually and culturally appealing and are implemented in a setting of the individual’s own choosing. This includes establishing realistic, achievable goals to meet the person’s needs, while also finding solutions for the barriers to participation that frustrate even the most enthusiastic participant. The program also has to be dynamic (i.e., interesting, enjoyable) and have the opportunity to change frequently to accommodate changes in the life of the participant (i.e., boredom, getting a new job, experiencing some pain performing certain types of exercises, etc.). So many programs fail because the individual or his or her environment changes and the program is no longer interesting or challenging, or the environment changes and the person no longer has access to the same resources needed to participate in the program or activity.

including the person’s motivational level (readiness to change), physical activity profile, health and mobility limitations, and barriers to participation, a program can be developed that meets each person’s specific needs, interests, and circumstances. Thus, physical activity recommendations for people with disabilities may be more effective if they are individually and culturally appealing and are implemented in a setting of the individual’s own choosing. This includes establishing realistic, achievable goals to meet the person’s needs, while also finding solutions for the barriers to participation that frustrate even the most enthusiastic participant. The program also has to be dynamic (i.e., interesting, enjoyable) and have the opportunity to change frequently to accommodate changes in the life of the participant (i.e., boredom, getting a new job, experiencing some pain performing certain types of exercises, etc.). So many programs fail because the individual or his or her environment changes and the program is no longer interesting or challenging, or the environment changes and the person no longer has access to the same resources needed to participate in the program or activity.

PEP Intervention Model

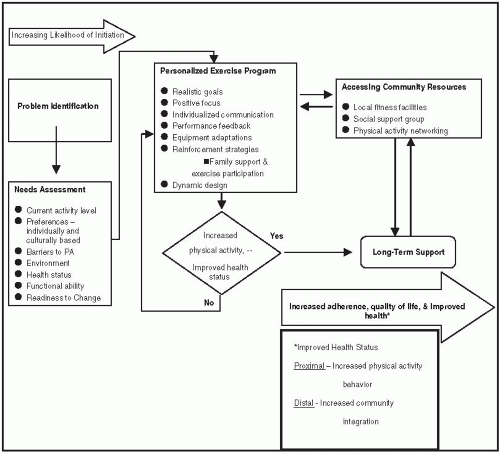

An example of an online resource that can assist rehabilitation professionals in providing more tailored physical activity recommendations to their patients/clients as they transition from in-patient rehabilitation to community-based activities is the Personalized Exercise Program (PEP). The PEP intervention model (shown in Fig. 54-2) begins with problem identification accomplished through a detailed assessment of the individual’s needs, interests, activity level, health status, functional ability, and readiness to change. This assessment of individual health, lifestyle behaviors, and function, in conjunction with an evaluation of the individual’s family support, community resources, and environmental barriers, allows a personalized physical activity program to be tailored for the individual. Jointly, individual-, family-, and community-level strengths and resources are harnessed to help the individual overcome barriers to physical activity.

While implementation of the resulting PEP intervention in the context of long-term support is expected to result in increased physical activity and improved health outcomes, more research needs to be conducted to determine the effectiveness of this model (21,22). Establishment and maintenance of social support networks are an important component of maintaining physical activity behaviors in people with disabilities. The individualized assessment, in conjunction with an evaluation of community resources (e.g., community swim programs, accessible fitness centers), allows for a personalized physical activity program that is based on customized information. Both individual and community-level strengths and resources are utilized to help the patient/client overcome barriers to participating in a sport or other type of physical activity at home or in the community. Establishment and maintenance of social support networks that include building community friendships with other people, in addition to parental and/or caregiver support, are important components for maintaining participation over an extended period until health benefits are achieved (21,22). These networks may include personal contacts with family members or caregivers or may involve friendships formed through exercise classes or nutritional cooking classes offered as part of a community-based program.

The dynamic design of the PEP intervention model and its person-centered approach allow the rehabilitation professional to revise and modify the program at any time until the recommendations are calibrated or recalibrated (as in the case with an illness or new secondary health condition) to the user’s needs and interest level. In Figure 54-2, the first step of the PEP intervention model is illustrated in the left column, comprehensive needs assessment, which includes the following components: (a) physical activity profile and activity preferences, (b) barriers to participation, (c) health status and mobility limitations, and (d) motivational level (readiness to change). Each of these components is described below.

Components of the PEP Intervention Model

Physical Activity Profile

Understanding the patients/clients’ physical activity participation history in sports, recreation, and/or fitness before (when possible) and after the onset of a disability is critical to

designing an effective program. An assessment of a patient/client’s specific disability and functional level, along with personal activity preferences, can help determine potential activities. For example, if a person with a spinal cord injury was an enthusiastic softball or basketball player before his or her disability, finding links to participating in wheelchair softball or basketball, whenever possible, may be more appealing and increase the individual’s participation. As discussed in the second section, any recreation, fitness, and sport activity can be adapted for a person with a disability that should motivate rehabilitation professionals to learn more about how this can be accomplished for certain clientele.

designing an effective program. An assessment of a patient/client’s specific disability and functional level, along with personal activity preferences, can help determine potential activities. For example, if a person with a spinal cord injury was an enthusiastic softball or basketball player before his or her disability, finding links to participating in wheelchair softball or basketball, whenever possible, may be more appealing and increase the individual’s participation. As discussed in the second section, any recreation, fitness, and sport activity can be adapted for a person with a disability that should motivate rehabilitation professionals to learn more about how this can be accomplished for certain clientele.

Barriers to Physical Activity

Personal and environmental barriers can impose substantial limitations in maintaining a physically active lifestyle. Among people with disabilities, some of the more common barriers are pain, lack of transportation, insufficient financial resources to pay for a health club membership, lack of awareness of community-based programs, and not knowing how to perform certain types of exercises or recreational activities. Usually, more specification is required in developing exercise programs for disabled populations because certain impairments and activity limitations can limit an individual’s access to a program or activity. As certain barriers are identified and removed, participation in various types of physical activities will likely increase.

One of the major concerns associated with increasing physical activity participation among people with disabilities is the lack of access to many community sports, recreation, and fitness programs (23). People with disabilities encounter enormous barriers in the built and natural environment (6). Indoor and outdoor structures have a major effect on participation in physical activity among people with disabilities (24,25). Structures such as gyms, fitness centers, outdoor trails, parks, and swimming pools often have poor signage, lack detail on how to use the equipment or participate in a program, or provide poor access routes to and from the facility or program.

Indoor environments of many fitness and recreation facilities also need to become more accessible for people with disabilities. One of the major barriers is inaccessible exercise equipment (26). Most manufacturers do not consider in their design specifications how to make their equipment accessible for people with physical, cognitive, and sensory disabilities. Typically, commercial cardiovascular exercise equipment requires propulsion by using the musculature of both lower extremities (i.e., treadmills, stationary bikes,

elliptical cross-trainers, and steppers), thereby restricting use among people with lower-extremity disabilities (e.g., paralysis, limb loss). While a few fitness facilities may be able to purchase a commercial quality arm cycle or wheelchair ergometer, the vast majority of fitness centers either cannot afford this equipment or do not find it cost-effective to purchase one for a small percentage of their clientele. Another problem with inaccessible equipment is that offering clients with disabilities the opportunity to use one piece of adaptive exercise equipment while the rest of the membership has access to all of the equipment clearly limits the amount of enjoyment and benefit that can be obtained from a more diversified program.

elliptical cross-trainers, and steppers), thereby restricting use among people with lower-extremity disabilities (e.g., paralysis, limb loss). While a few fitness facilities may be able to purchase a commercial quality arm cycle or wheelchair ergometer, the vast majority of fitness centers either cannot afford this equipment or do not find it cost-effective to purchase one for a small percentage of their clientele. Another problem with inaccessible equipment is that offering clients with disabilities the opportunity to use one piece of adaptive exercise equipment while the rest of the membership has access to all of the equipment clearly limits the amount of enjoyment and benefit that can be obtained from a more diversified program.

People with visual or cognitive disabilities also have difficulty using various types of exercise equipment (27). Display panels are often difficult to read or understand, getting on and off the equipment presents some risk of falling, and machines are often hard to propel or lift (e.g., weights are too heavy to lift) for people with low strength levels.

Programmatic issues are also barriers for people with disabilities (28). Fitness and recreation classes such as aerobic dance, yoga, and tai chi are often taught by instructors who have minimal knowledge of how to adapt their program for someone with a disability. Spoken directions regarding the types of exercises or movements the class is being asked to perform tend to be terse or vague. Rehabilitation specialists must have a good understanding of how to overcome certain barriers in order to ensure that the patient/client can successfully participate in various types of community-based programs.

Health Status and Mobility Limitations

A rehabilitation professional must also understand the health and mobility limitations that prevent a patient/client from engaging in certain types of physical activities. Various types of disabilities include impairments such as loss of balance, vision, hearing, pain, fatigue, decreased cognition, paralysis, and many others. Each of these impairments can have an effect on the physical activity recommendations. Similarly, mobility limitations such as difficulty walking, climbing steps, transferring from a wheelchair, etc., must all be considered when designing a physical activity program that will match the individual’s functional level.

Motivational Level

Finally, for successful participation in any form of physical activity, the rehabilitation professional must find innovative ways to encourage participants to obtain regular physical activity. People with disabilities are often demotivated because of a number of barriers preventing them from becoming physically active (6). The stages of change model (29,30) includes five stages: precontemplation—no intention to change a behavior in the foreseeable future; contemplation—awareness that he needs more physical activity but has not yet made a commitment to take action; preparation—intending to take action in the next month but has unsuccessfully taken action in the past year; action—interested in modifying behavior to increase physical activity; and maintenance—individual is engaging in physical activity. The stage of change that a patient/client is experiencing is often dependent on personal and environmental barriers. Therefore, assistance in identifying and addressing these barriers, helping the individual to appreciate the benefits of regular physical activity, as well as greater access to various forms of physical activity can help improve physical activity participation.

Community-Based Physical Activity Options

The need to continue the recovery process after an injury or disability must include access to various types of physical activities in the person’s community (31,32). In order to avoid boredom or lack of interest in a specific physical activity program, it is optimal to offer as many activity options as possible. Certain individuals may prefer group exercise (i.e., an aqua-aerobics class) in a community-based setting, while others may choose to exercise alone in their home or engage in some form of outdoor activity. Regardless of preference, a variety of options should be available. In the second section, such community-based physical activity options and resources are reviewed.

Types of Physical Activities

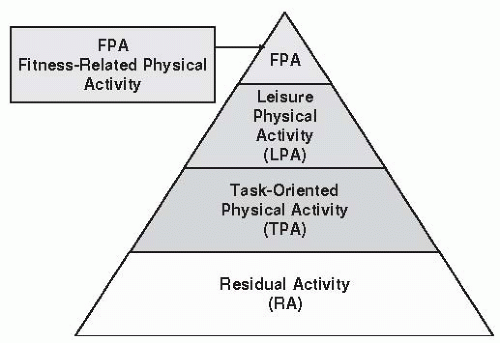

The pyramid in Figure 54-3 illustrates different types of physical activities that can be engaged in over the course of the day. With rising obesity rates and low levels of energy-requiring activities at work and home, it is critical that all forms of physical activity be increased over a 24-hour period. Even simple movements (i.e., moving between commercials) can result in substantial accumulations of energy expenditure over the course of the day.

At the base of the pyramid is residual activity. This type of activity is generally performed at a very low intensity threshold and involves frequent unstructured movements, such as getting up and down from a chair, walking into different areas of the home, fidgeting, moving arms, etc. While residual activity does not offer any formal mechanism for structuring physical activity, the more an individual moves during the day, the higher the energy expenditure. Any activity above sitting, lying down, or sleeping requires greater energy expenditure and therefore higher calorie output.

The next level of the pyramid is task-oriented physical activity. These types of activities relate to certain indoor and outdoor household tasks such as cleaning, doing laundry, shopping, driving a car, doing yardwork, etc. Several of these activities can be strenuous in nature and provide effective ways to increase energy expenditure in individuals who generally have low levels of physical activity or are somewhat deconditioned and/or uninterested in engaging in structured activities. The third level of the pyramid is leisure physical activity, which includes structured and planned physical activities such as leisure walking, bike riding, hand cycling, outdoor yard games, bowling, team and individual sports, fishing, etc. This form of physical activity can range from very low to moderate intensity activity. At the top of the pyramid is fitness-related activity, which is the most strenuous type of activity, with the highest rate of return in terms of improving health and function.

Rehabilitation professionals can assist their patients/clients to incorporate each level of physical activity within their daily regimen so that daily energy expenditure is increased. For example, residual activity can be performed at regular intervals during the day (i.e., get up or push wheelchair to another room between commercials, spend 5 minutes at the end of every hour moving arms or legs); to increase task-oriented physical activity, more chores can be completed inside and outside the home (i.e., dusting, cleaning windows, mopping or sweeping floor, cleaning appliances, grocery shopping, etc.); leisure physical activity can include new hobbies, such as tennis or bowling, leisurely walks or rolls for a few minutes several times a day, joining a chair exercise class, etc. Fitness-related activities can generally be performed for less than 1 hour, compared to the other forms of physical activity that are demonstrated at lower intensity thresholds. The next section provides many different recommendations for increasing two types of physical activities, leisure/sports, and fitness-related activity.

RESOURCES IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND DISABILITY FOR REHABILITATION PROFESSIONALS

One of the most important elements of this chapter is to provide rehabilitation and health professionals with a one-stop resource for identifying physical activity materials that can be used to facilitate/promote/prescribe participation among people with various types of physical, cognitive, and sensory disabilities. While textbooks provide a framework for guiding professionals in planning and developing rehabilitation programs, when it comes to physical activity, the Internet is extremely important for identifying key resources that can be passed on to the patient/client including specific information related to his or her disability and engaging in various types of physical activities, resources on how to exercise or use an exercise facility, and, most importantly, video clips demonstrating various types of exercises or physical activities that are easier to visualize than explain. The National Center on Physical and Disability has been funded since 1999 to promote physical activity among people with disabilities. This resource center will allow clinicians to identify materials, programs, etc., for their patients/clients.

The National Center on Physical Activity and Disability

As has been discussed in the first section, participation in fitness, recreation, and sport is more likely to succeed if programming is tailored to the participant’s abilities and interest levels, while simultaneously addressing the barriers that these individuals may encounter for participating in such activities. The National Center on Physical Activity and Disability (NCPAD, www.ncpad.org) addresses these problems by making sports and physical activity programs more accessible to people with disabilities through advanced Internet technologies that can assist rehabilitation professionals to develop appropriate, accessible physical activity programming (Fig. 54-4).

NCPAD serves as a central repository of information on physical activity and disability, actively collecting information from research, best professional practices, information on public and private recreation and fitness facilities serving people with disabilities, and businesses that provide equipment and services supporting physical activity participation by people with disabilities. In addition, NCPAD has actively promoted the importance of physical activity in attaining and maintaining optimal health for people with disabilities. This is being accomplished through a variety of promotional resources and outreach activities in partnership with advocacy organizations, service providers, and individual consumers.

Rehabilitation professionals can use the NCPAD web-based resources when designing treatment programs for patients/clients that include acute care guidelines, in addition to web-based physical activity assessment tools, and information on community-based resources and activity programs that promote long-term physical activity maintenance.

NCPAD’s information is centralized on its Web site (www.ncpad.org), which provides a range of resources on physical activity and disability: information on physical activity and disability, networking opportunities, searchable databases, assessment tools, and research. NCPAD Information

Specialists are available at 800-900-8086 or ncpad@uic.edu to answer questions, including but not limited to appropriate exercise for individuals with a specific disability, available adaptive equipment, the location of accessible fitness programs and sport team opportunities, and more.

Specialists are available at 800-900-8086 or ncpad@uic.edu to answer questions, including but not limited to appropriate exercise for individuals with a specific disability, available adaptive equipment, the location of accessible fitness programs and sport team opportunities, and more.

Information on Physical Activity and Disability

Factsheet topics include physical activity (i.e., lifetime sports, competitive sports, exercise/fitness, and leisure), disability/health conditions, nutrition, and wellness. Factsheets on specific disabilities, for example, encompass an overview of the disability; aerobic, strength, and flexibility components for developing an appropriate fitness program; precautions and safety guidelines for exercising with a specific disability; and key organization contacts and references by local community. Sports and recreation factsheets provide general information about the benefits of the activity, rules and regulations, and key contact organizations. Many factsheets have embedded video clips so that the specific sport or exercise technique can be demonstrated to the user (http://www.ncpad.org/videos/), and some are available as videos/DVDs/quick series booklets that can be purchased at NCPAD’s web shop (http://www.ncpad.org/shop/). NCPAD’s free monthly newsletter (http://www.ncpad.org/newsletter/newsletter.php?letter=current) also provides updates on new NCPAD resources, fitness trends for people with disabilities, secondary condition prevention, as well as information on events and conferences, grants, and employment information.

Searchable Databases

NCPAD’s online searchable databases can assist professionals in locating appropriate physical activity programs and organizations, adaptive equipment and devices, and qualified personal trainers. These resources can help rehabilitation professionals involve their patients/clients in community-based physical activities and sports and/or obtain physical activity support and training from fitness professionals.

A web-based directory of accessible physical activity programs (including sports, recreational, and exercise/fitness activities) for people with disabilities and chronic health conditions (http://www.ncpad.org/programs/) and organizations providing health promotion and community-based resources for people with disabilities (http://www.ncpad.org/organizations/) may be searched by geographic area or topic. A suppliers database (http://www.ncpad.org/suppliers/) contains information on equipment and assistive devices for sports and recreation for people with disabilities, and a personal trainers database (http://www.ncpad.org/trainers/index.php), also searchable by geographic area, supplies information about personal trainers who have experience working with people with disabilities and chronic health conditions.

Networking Opportunities

Web-based forums in the areas of networking (exercise professionals, exercise buddies), adaptive equipment, community resources (services, funding, programs), research (grants, articles), adherence ideas/suggestions, and best practices on accessibility (http://www.ncpad.org/) can help rehabilitation professionals exchange information, above and beyond that available through the NCPAD Web site and the Information Specialists. The “Your Writes” section (http://www.ncpad.org/yourwrites/) also provides articles and information written by people with disabilities, family members, and caregivers on health promotion opportunities and resources for people with disabilities.

Assessment Tools and Research

NCPAD and its related projects include assessment instruments and resources on evaluating physical activity levels and accessibility for people with disabilities to participate in fitness and recreation programs and facilities. Additionally, resources are available to assist professionals who are developing evidence-based programs, applying for grants, or designing a research study.

Evaluation tools include the PADS (Physical Activity Disability Survey) and B-PADS (Barriers to Physical Activity and Disability Survey) instruments. The PADS is designed to assess low-level physical activity among persons with physical disabilities and chronic health conditions (http://www.ncpad.org/) and the B-PADS, barriers to physical activity encountered by persons with disabilities, specifically personal (e.g., lack of motivation, fear of leaving home, perception of exercise as difficult or boring) and environmental barriers (e.g., lack of transportation, costs, and availability of fitness and recreation facilities). Assessment tools can also help to regularly measure steps logged per day, as well as body mass index and weight.

NCPAD’s AIMFREE (Accessibility Instruments Measuring Fitness and Recreation Environments) manuals are a validated series of questionnaire measures that can be used by persons with mobility limitations and professionals (i.e., fitness and recreation center staff, rehabilitation professionals, owners/managers of fitness centers) to assess the accessibility of recreation and fitness facilities, including fitness centers and swimming pools. The instruments are available for purchase at NCPAD’s web shop (http://www.ncpad.org/shop/).

For rehabilitation professionals interested in research, the Web site references section provides listings of books, journals, newsletters, videos, pamphlets, reports, theses, and proceedings (http://www.ncpad.org/refs/books/). Abstracts of current research articles on physical activity and disability are available at http://www.ncpad.org/research/ and presentations on physical activity and disability at http://www.ncpad.org/presentations/. The monthly NCPAD newsletter also contains up-to-date information on grants and events/conferences (http://www.ncpad.org/newsletter/newsletter.php?letter=current) and includes information on new or interesting recreation, leisure, and sports programs offered to people with disabilities throughout the country.

Fitness Programming for People with Disabilities

Physical fitness is an important area of emphasis in improving health among people with disabilities. The three primary components of fitness include cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular strength and endurance, and flexibility.

Cardiorespiratory endurance or aerobic capacity refers to the ability of the heart (cardio) and lungs (respiratory) to provide sufficient blood flow to working muscles for sustained

physical activity. Muscular endurance is defined as the muscle’s ability to exert force for a sustained period of time, and muscular strength refers to the ability to generate force one time. Both contribute to improved balance, mobility, and stability, as well as improvements in BADL and IADL. Flexibility is the movement capability (i.e., range of motion) of muscle groups around a joint and can help to reduce injury, improve posture, and perform ADL and IADL (33

physical activity. Muscular endurance is defined as the muscle’s ability to exert force for a sustained period of time, and muscular strength refers to the ability to generate force one time. Both contribute to improved balance, mobility, and stability, as well as improvements in BADL and IADL. Flexibility is the movement capability (i.e., range of motion) of muscle groups around a joint and can help to reduce injury, improve posture, and perform ADL and IADL (33

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree