INTRODUCTION

Sexuality is an integral part of being human and is a vehicle to demonstrate attraction, intimacy, and commitment. Because of this, sexuality persists beyond reproductive years and/or good health. Persons with disabilities often feel that since significant changes to their sexuality are not life threatening, sexual concerns do not merit attention by health care professionals. Nothing can be further from the truth. Sexuality is highly important and medically legitimate and greatly affects quality of life. When surveyed about what “gain of function” was most important to their quality of life, men and women with spinal cord injury (SCI) stated that sexuality was a major priority even above the return of sensation, ability to walk, and normal bladder and bowel function (

1), that SCI altered their sexual sense of self, and that improving their sexual function would improve their quality of life (

2,

3).

In this chapter, we focus on sexuality in those persons with physical disability versus mental, cognitive, or developmental disabilities. When a condition becomes chronic or gradually debilitating, expectations of

recovery must give way to pursuit of

adaptation (

4). “Sexual rehabilitation” not only implies salvaging and restoring remaining function but also implies remaking and readjusting. Only in the arena of sexuality can rehabilitation go beyond the local affected area. Loss of physical, sensory and motor options forces an appreciation of the power of “brain or cerebral sex” and the development of evolved sexual experience through the process of “neuroplasticity.” This is best explained by the analogy of how, despite the “hardware” being altered by disability, the “software” can still be intact and adaptable (

5). Research is just starting to address the potential of “sensory substitution” in persons with disability (

6). In the medical treatment of sexuality after disability, the mind-body interaction cannot be forgotten by the clinician or the therapeutic value of this potential is lost.

SEXUAL NEUROPHYSIOLOGY

Both somatic and autonomic nerves provide important sexual afferent and efferent communication between the brain and periphery. Autonomic nerves are activated by stretch or lack of oxygen, rather than by touch or temperature (

12). In the somatic system, tactile inputs include light touch, temperature, pressure, vibration, and pain. It appears that both somatic and autonomic nerves appear critical to recognize stimuli as “sexual” (

12). The cerebral evaluation of skin and visceral stimulation; of visual, gustatory, and auditory inputs; and of fantasy and emotion forms either a sexually excitatory or inhibitory signal. This generated neuronal “trigger,” coordinated in the limbic system, hypothalamus, and other midbrain structures, is carried distally through the brainstem and spinal tracts and can be modulated by mood, hormones, emotions, and physical factors (

4). In everyday life, this signal is usually inhibitory, until engagement of sexual activity is deemed appropriate and excitatory signals dominate, instigating the triggering of spinal cord reflexes for sexual function. Performance anxiety, distraction, and fear of negative consequences of being sexual (i.e., ED) can cause the supratentorial inhibition on the spinal cord reflexes to remain. In chronic disease or neurological conditions, signals may be directly disrupted by nerve injury or nerve degeneration, the physiology of an end organ and its ability to respond to the stimulus can be altered, or pain or other limitations can cause distraction away from the sexual focus, rendering sexual response unreliable.

Once the descending signal has passed down the spinal cord, the pelvic sexual organs receive their information from the spinal cord via three nerve pathways: (a) sacral parasympathetic (pelvic nerves and pelvic plexus), (b) thoracolumbar sympathetic (hypogastric nerves and lumbar sympathetic chain), and (c) somatic (bilateral pudendal nerves) (

13). More attention is being paid to try and preserve these nerve tracts in pelvic surgery to reduce the amount of resulting sexual dysfunction (

14,

15). Sexual arousal leads to genital erectile tissue engorgement and pelvic vasocongestion via vasodilatation of arteries and smooth muscle relaxation. In women, lubrication depends on both intact innervation and normal estrogen levels (

16), and in men, internal accessory organ function (including the production of semen) and erection are dependent on adequate testosterone levels.

There are two neurological pathways for

genital arousal: reflexogenic and psychogenic. While psychogenic and reflexogenic pathways can act independently, they usually act synergistically to determine the genital response via a final common pathway involving a sacral parasympathetic route (

13). The

reflexogenic pathway, triggered by direct stimulation of the genital organs, has an afferent component conveyed by the pudendal nerve to the S2-4 segments of the spinal cord (

17). The responding efferent component returns through the sacral parasympathetic center, contributing fibers to the pelvic nerve and onto the cavernosal nerves at the genitalia. The

psychogenic pathway is of supraspinal origin (auditory, imaginative, visual, etc.) involving the medial preoptic nucleus (MPOA), paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, and reticular activating systems (the latter involved with nocturnal arousal during REM sleep) (

14). The long efferent tracts from the central nervous system between cortex, cord, and autonomic nervous system must be intact to elicit the thoracolumbar sympathetic center and the sacral parasympathetic center (

17). Complete spinal cord injury (SCI) above the level of the psychogenic pathway eliminates the connection to it and the natural supratentorial inhibitory control, enhancing the reflexogenic mechanism initiated by touch (

14). SCI involving the lumbosacral region results in loss of reflexogenic but not psychogenic capacity, since the pathway from the brain to the thoracolumbar center is still intact. The sympathetic nervous system can maintain genital arousal capacity after injury to parasympathetic pathways (

13), and has a role in the development of psychogenic arousal (

18). Both men and women undergo measurable genital arousal during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (

16,

19). In men, the presence of REM sleep (morning) erections is a sign that daytime erection problems are

more likely psychogenic in nature. An exception is in multiple sclerosis (MS), where, despite organic disturbance with daytime, erotic erections, nocturnal erections can be frustratingly preserved (

20).

At the genital level, cavernosal smooth muscle relaxation results in vasocongestion, tumescence, and elongation of the erectile tissue in both men and women. The tunica albuginea, a fibroelastic stocking surrounding the corpora cavernosa, becomes stretched with tumescence, tightening its elastic fibers and kinking the emissary veins that pierce it. This occludes the venous blood outflow while high pressure arterial inflow continues. In men, this veno-occlusive mechanism, along with bulbocavernosus (BC) muscle contraction, results in a rigid erection and ischiocavernosus (IC) muscle contraction helps propel ejaculated semen (

14,

21). In women, the veno-occlusive mechanism is less prominent due to a less effectual tunica (

16). Vaginal lubrication (a plasma transudate from the blood circulating through the vessels of the vaginal epithelium), lengthening of the vagina, and uterine, urethral, labial, and pelvic ligament vasocongestion occurs with female arousal (

15). Passive dilation of the vagina results in a reflex contraction of both the BC and IC, indirectly affecting the clitoris and sensory perception of the clitoris (

22). Spasm of either the BC or IC muscles, or injury to their pudendal innervation can

effect subjective sexual arousal and orgasm. Priapism can occur in both sexes, and a persistent arousal syndrome, potentially of organic origin, has been newly recognized in women (

23,

24).

While arousal is predominately parasympathetic,

ejaculation is primarily a sympathetic phenomenon. Preganglionic sympathetic fibers leave the spinal cord from the first and second lumbar segments, synapsing and eventually distributing to the vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and the prostate through the hypogastric nerves, stimulating smooth muscle contractions (

12). Ejaculation occurs in two phases: seminal emission (sympathetic T10-L2) and propulsatile ejaculation or expulsion (parasympathetic S2-4 and somatic). Seminal emission involves transport of semen into the prostatic urethra via the ejaculatory ducts in the prostate. The sympathetic hypogastric nerve (L1, L2) activity closes the bladder neck to prevent retrograde ejaculation. A sense of impending “ejaculatory inevitability” proceeds propulsatile ejaculation and the seminal bolus is then propelled distally out the urethral meatus (

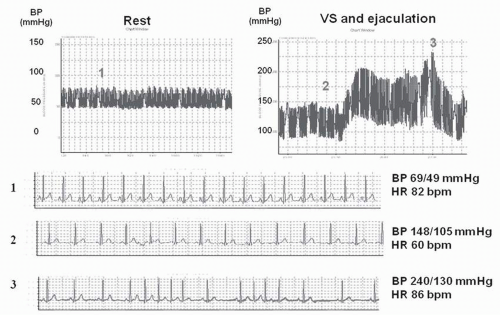

14). Orgasm usually occurs with ejaculation, but they are not synonymous and are separate neurological entities.

Orgasm appears to be relayed through both the somatic and autonomic systems (

23), but neurologically, orgasm is the least understood of the sexual phases. It is a complicated combination of local spinal cord reflexes and cerebral and autonomic influences, any of which could potentially dominate in any one orgasmic experience or be adequate within themselves. “Orgasm” after disability may include orgasmic attainment without genital stimulation (i.e. “eargasms” after SCI, orgasm arising from breast stimulation alone, etc). For example, about half of men and women with complete SCI can still experience orgasm, and a few neurophysiological theories have been proposed for this phenomenon (

25). Strength of the pelvic floor contractions (somatic), the degree of engorgement of the internal genitalia (autonomic), subjective awareness of internal genitalia contractions (i.e., uterine), duration and degree of brain arousal, and interpretations of cardiovascular alterations with sexual activity are all factors in the subjective intensity of orgasmic release. While estrogen does not seem to influence the orgasmic potential in women, low androgen levels make orgasm more difficult to reach in both men and women (

26). Oxytocin levels may rise during arousal and orgasm, and prolactin levels remain elevated after orgasm (

23), but the significance of this is not known.