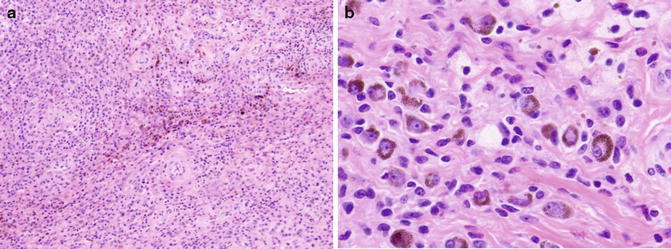

Fig. 1

(a) 4× and (b) 40× H + E stain from loose bodies after surgical removal demonstrating discrete hyaline cartilage nodules with chondrocytes with mild atypia (Courtesy of University at Buffalo Orthopedic Oncology Database)

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The clinical presentation for synovial chondromatosis is that of a gradual onset of monoarticular pain and stiffness with mechanical complaints of locking and catching. In the hip specifically clinical signs are more obscured since it is more difficult to detect loose bodies or an effusion on exam. It most commonly involves the knees (50–65 %) of cases, followed by elbows (20–25 %) while hips account for only 10 % of cases. Males are twice as likely to be affected as females. It typically presents during the third to fifth decades of life [9].

X-rays are normal in greater than 50 % of cases because the cartilage in the loose bodies is not well ossified and can result in delayed diagnosis. By the time loose bodies are apparent, the disease can have progressed significantly, and multiple radiopaque round or oval lesions are seen as well as a joint effusion, degenerative arthritis, osteophytes, and subchondral sclerosis (Fig. 2). CT scan can be useful to visualize loose bodies that are not seen on X-ray and will demonstrate distension of the capsule. MRI is also often useful if there is an unclear diagnosis from radiographs. Kramer et al. described three different types of MRI imaging [10]. Pattern A (12 %) is described as a lobulated homogeneous intra-articular signal isointense to muscle on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Pattern B (80 %) incorporates the features of pattern A with addition of signal void foci on all pulse sequences. Pattern C (8 %) has features of patterns A and B plus foci of lesions with peripheral low signal surrounding a central fatlike signal. The significance of the various imaging in prognosis and pathogenesis is unclear at this point. Magnetic resonance arthrography with gadolinium contrast will show multiple filling defects in the joint (Fig. 3). Bone scan may show increased uptake around calcified loose bodies.

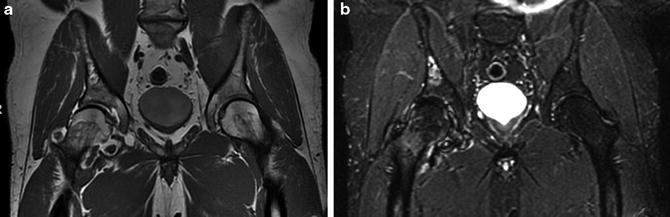

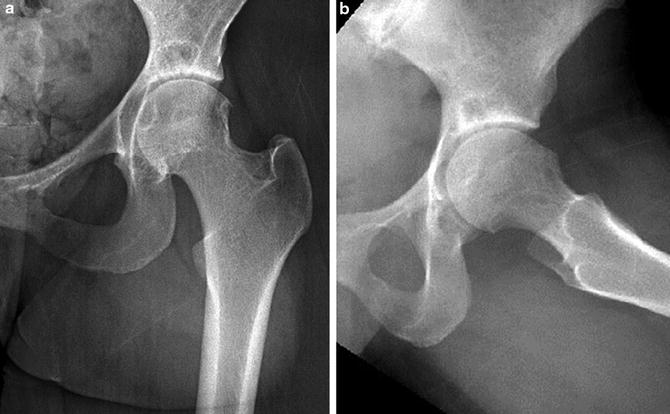

Fig. 2

(a) AP and (b) frog leg lateral radiographs of a 42-year-old male with right hip pain associated with synovial chondromatosis. Note the loose bodies seen throughout the hip joint and arthritic changes seen in the femoral head (Courtesy of University at Buffalo Orthopedic Oncology Database)

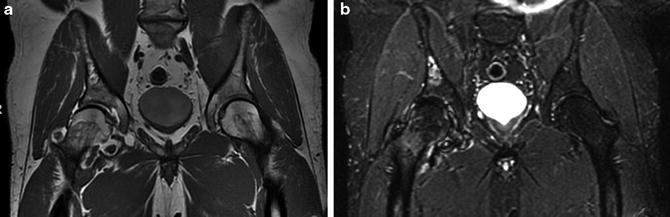

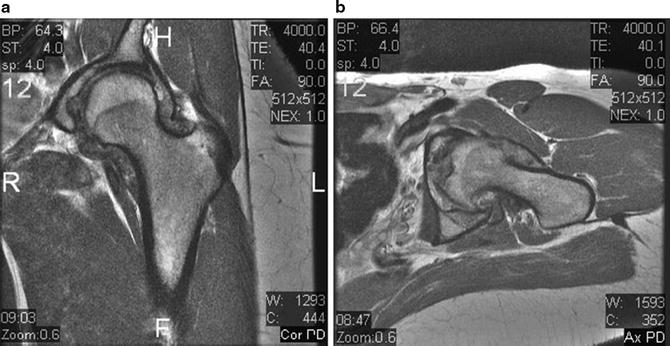

Fig. 3

MRI arthrogram coronal (a) T1 and (b) STIR sequences from a pelvis of a 42-year-old male with right hip pain associated with synovial chondromatosis. Again loose bodies are seen within the hip joint (Courtesy of University at Buffalo Orthopedic Oncology Database)

Other causes of loose bodies and intra-articular pathology need to be considered when considering a diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis. The differential includes tumors, synovial sarcoma, fragmented osteophytes in OA, or osteochondral dissecans. However, in these conditions, loose bodies will typically be smaller in both number and size. Intra-articular calcifications can also be seen with rare hemangiomas, villonodular synovitis, or post-septic arthritis.

Treatment

The treatment of synovial chondromatosis includes surgical removal of loose bodies with partial or complete synovectomy. While it has been agreed that it is necessary to remove the loose bodies in order to relieve the symptoms of pain, stiffness, and locking that the patients often present with, the role of synovectomy to prevent further damage is currently still debated. In Milgram stage 3 and secondary disease, synovectomy may not be as important since there is less expectation of the generation of further loose bodies. However, in diffuse primary disease, evidence has accumulated that synovectomy is very important in preventing recurrence in both the knee and the hip [11].

In the hip, the standard treatment involves a surgical dislocation in order to facilitate loose body excision and synovectomy. This surgical dislocation can be performed through a Watson-Jones approach or through an anterior Smith-Peterson approach with Ganz dislocation of the hip [12–14]. Some authors have described using the trochanteric osteotomy to improve visualization, allow dislocation, and assure complete synovectomy. Occasionally, a small posterior capsulotomy has been performed to facilitate removal of loose bodies [15]. Successful arthroscopic management of synovial chondromatosis has also been described. However, this involves selective patients with limited focal disease and increases the risk of recurrence [16–19]. Recurrence rates with synovectomy have been described between 0 % and 23 %.

If synovial chondromatosis is not diagnosed early and treated promptly, the loose bodies themselves can cause significant damage to the labrum and cartilage generating secondary osteoarthritis. Late complications such as secondary hip subluxation [20] and femoral neck fractures have been described [21]. Also, rare but described has been degeneration into chondrosarcoma [22]. The outcome for many of these patients with significant articular damage may be total joint arthroplasty or resurfacing [23, 24]. Even in the presence of an arthroplasty, there is the possibility of recurrence of the disease.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

Pathophysiology

Pigmented villonodular synovitis is another benign proliferative disorder of the synovium in the joint, tendon sheath, and bursa. While the lesion is benign, it can be locally aggressive and cause the destruction of both intra- and extra-articular structures. The true pathophysiology of this process is still incompletely understood. Jaffee et al. considered the disease to be a reactive inflammatory response [25]. In a recent review, 56 % of patients with PVNS were associated with trauma to the joint [26]. There is reason to believe that it has neoplastic characteristics as evidenced by its monoclonality, metastatic potential [27], presence of chromosomal abnormalities [28], and aneuploidy [29]. PVNS is characterized by a proliferation of synovial-like mononuclear cells, with multinucleated giant cells, lipid- or hemosiderin-laden macrophages, and inflammatory cells. The hypertrophic, hypervascular synovial tissue will have villous, nodular, or a combination of proliferative shapes. Hemosiderin is deposited in the macrophages within the synovium . The inflammatory cells secrete cytokines which stimulate osteoclasts to act and resorb both periarticular bone and damage cartilage.

There are two types of PVNS described including a diffuse and a localized type. It most often affects the knee rather than the hip, but any synovia can be affected. The diffuse type can be more aggressive and recur more frequently. It has high cell proliferation rate and cell atypia. The focal or localized forms often occur as discrete nodular lesions involving tendon sheaths and are often known as giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath. These occur more often in the hands and feet but can be present in the hip. These lesions are often well circumscribed and have a lower recurrence rate.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The presentation of PVNS in the hip involves slowly progressive monoarticular pain, stiffness, locking, and decreased range of motion. Patients may report a slow-growing mass that is palpated in the local form. In the diffuse articular form, there will be pain with extremes of range of motion of the hip. It presents in slightly higher frequency in women than men and is most frequently encountered in the third and fourth decades [30].

Radiographs of the hip will commonly show bone erosion or cysts. Joint space is typically preserved and there may be an effusion [31, 32] (Fig. 4). In early disease, radiographs are commonly normal. Hemosiderin will be detected on CT scan, and this form of imaging can be useful to determine the extent of the synovial involvement and bone erosion or cysts. Diffuse thickening of the tissue around the joint will be demonstrated.

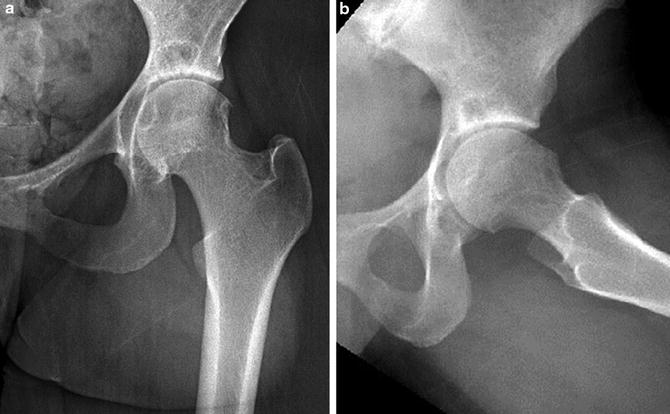

Fig. 4

(a) AP and (b) frog leg lateral of a 28-year-old female with left hip pain due to PVNS. Early erosive changes are demonstrated (Courtesy of University at Buffalo Orthopedic Oncology Database)

On MRI “bloom” artifacts will be created by the hemosiderin deposits and appear as low or absent petal-shaped areas on both T1- and T2-weighted images which distort the surrounding image (Fig. 5). MR arthrogram will show extensive synovial thickening with villous or nodular projections. It is not expected to see multiple filling defects like synovial chondromatosis [33]. PET imaging has been used to document treatment when following recurrent disease [34] but not for primary diagnosis.

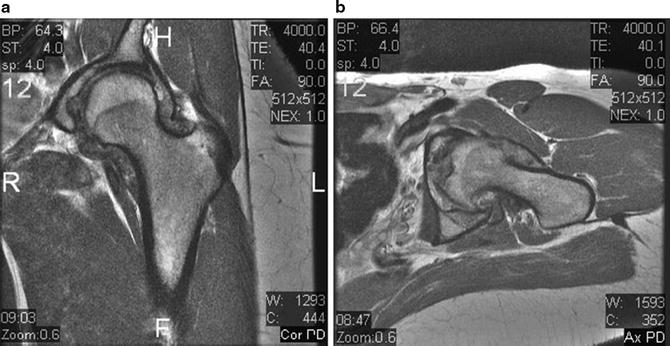

Fig. 5

(a) Coronal and (b) axial cuts from T1 MRI from a 28-year-old female with left hip pain associated with PVNS. Present is thickened villous synovium and bloom artifact (Courtesy of University at Buffalo Orthopedic Oncology Database)

On gross examination of the tissue, the diffuse form of PVNS is a tan mass of villi and folds of synovium . There can be both sessile and pedunculated nodules present. The local form of PVNS is usually a well-circumscribed, pedunculated, firm nodule. PVNS on histological examination will show synovial cell hyperplasia both on the surface of the synovium and deeper into the involved tissue. Giant cells, hemosiderin, and foam cells will be scattered throughout (Fig. 6).