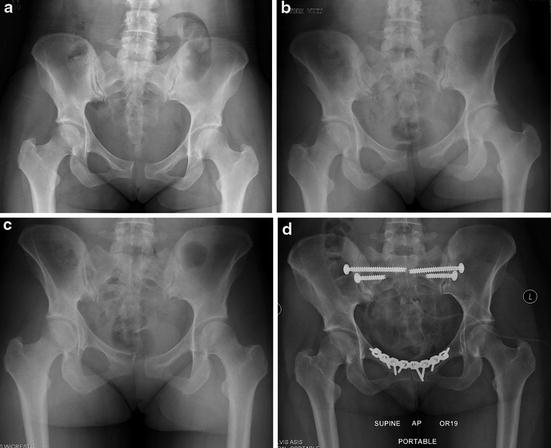

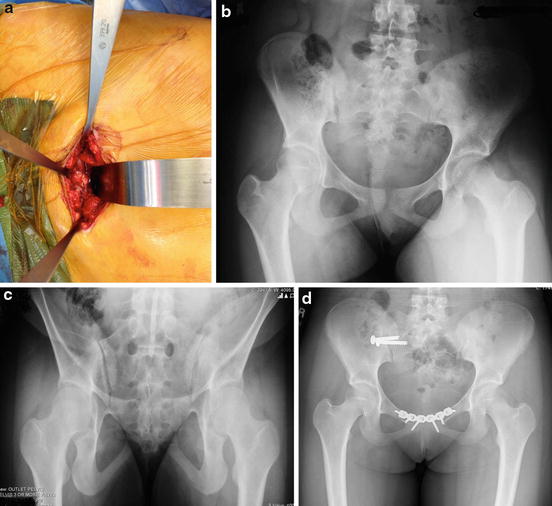

Fig. 1

“Flamingo views” can be beneficial as this is a dynamic maneuver demonstrating potential instability, re-creating a vertical shear-type moment on the pubic symphysis and SI joint. The definition of instability is debatable with 2 mm of vertical translation or 7 mm of widening being abnormal by most reports [2, 19, 52]. Garras et al. found statistically significant differences in multiparous patients when compared to men and nulliparous patients on flamingo views, with an average of 3.1 mm of translation vs 1.4 and 1.6 mm, respectively [28]. Siegel et al. examined the use of flamingo views in a series of 38 patients referred for “pelvic pain” and history consistent with instability [27]. They defined abnormal motion at the symphysis with flamingo views as >5 mm. In total, 66 % of patients had more than 5 mm of motion. Perhaps more importantly is the fact that supine or two-legged stance films were unable to pick up this instability, enhancing the potential benefit to dynamic radiographs in aiding the diagnosis. (a–c) demonstrates an AP pelvis followed by standing on the left and then the right leg with the shift in the pubic symphysis. Despite this instability, the patient was managed conservatively and did well from a clinical standpoint

Surgery should be considered only when conservative treatment fails. A trial of nonoperative therapy should be attempted for at least 3 months in the initial phase of injury (if seen within 6 months of initial symptoms) including therapy, injections, and anti-inflammatories. However, after 4–6 months from injury or onset of symptoms, less significant improvements with conservative therapy are typically seen (especially with postpartum instability) [18, 30], and a discussion with the patient as to continued conservative vs surgical management is appropriate. Clinical history and physical exam are key for surgical planning. If the patient has pain subjectively in the anterior pelvis/groin as well as posteriorly (right or left SI joint), then consideration to anterior pelvic stabilization as well as posterior SI joint stabilization should be given. Flamingo views are routinely used for assessment and documentation of hemi-pelvic instability, with focus on differential hemi-pelvic motion as opposed to exact numerical measurements of that motion. The one exception to the above “watchful waiting” is the case of acute traumatic pelvic disruption following childbirth. In this case, many authors have suggested this pelvic injury sustained during parturition should be considered along the same lines as traumatic pelvic disruption and classified within the spectrum of open book pelvic injuries [49]. Figure 2 shows a patient without pain prior to delivery. Given the wide separation anteriorly as well as disruption of bilateral SI joints (essentially an anterior-posterior compression type II injury), surgical intervention was undertaken with good early results. Table 1 lists potential surgical indications.

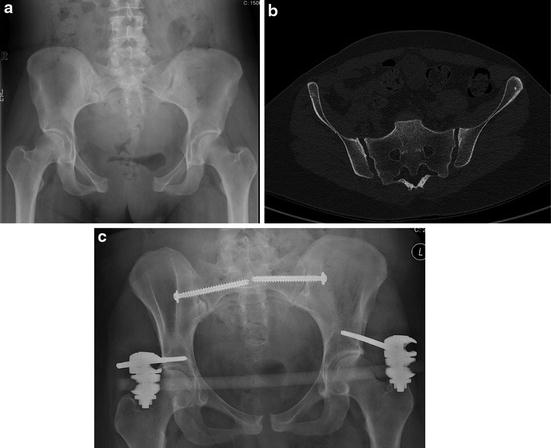

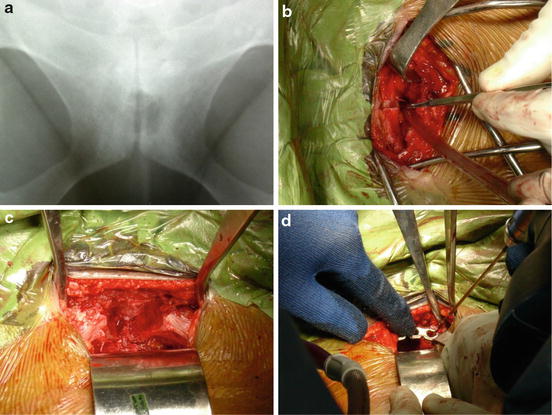

Fig. 2

(a) AP pelvis of a patient who present 10 days after vaginal delivery and 8 cm pubic diastasis with bilateral SI joint widening. (b) CT scan of the same patient demonstrating widening of the bilateral SI joints. (c) Postoperative AP after placement of external fixator and bilateral SI screws. Given the time from delivery, an open anterior approach was contraindicated given the potential for significant bleeding secondary to pregnancy changes

Table 1

Surgical considerations for pelvic instability

1. Failure of conservative therapy (including physical therapy, corticosteroid/analgesic injection, cessation of lactation if postpartum pain, etc.) >3 months |

2. >6 months of pain since onset of symptoms, especially postpartum, without significant improvement along with radiographic instability |

3. Radiographic instability on flamingo views with a clinical history of anterior pubic pain/groin pain +/− posterior pain |

4. Acute, traumatic postpartum injury (i.e., APC II pelvic ring injury) |

5. Response to therapeutic/diagnostic corticosteroid/analgesic injection to the pubic symphysis or SI joint with resolution of symptoms (typically series of three injections) |

Surgical treatment of pelvic instability and osteitis pubis is limited to case series alone and can be divided into anterior and posterior fixation strategies. Anteriorly, reports of surgery including curettage of the symphysis, polypropylene mesh, and stabilization with or without bone grafting have been reported [26, 50]. Choi et al. identified six case series of surgical intervention for osteitis pubis [4]. A total of 25 athletes have been reported as treated with simple curettage of the pubic symphysis [4]. Of those patients, 72 % were able to return to sport at an average of 5.6 months [4]. Radic et al. examined the role of pubic symphysis curettage in 23 patients who had failed conservative therapy [51]. While pain scores did not statistically differ pre- and postoperatively, 61 % of patients were able to return to full sporting activity. However, 26 % of patients had recurrence of symptoms which resolved with rest and therapy in a range of 8–18 months postoperatively. At final follow-up, 30 % of patients following the procedure were unable to return to their previous level of sporting activity. Surgical stabilization of the anterior pelvic ring with or without bone grafting has been reported in two series with eight patients [4]. Return to sport was noted an average of 6.6 months in those eight patients. Williams et al. treated seven rugby players with osteitis pubis over the course of 12 years who were recalcitrant to conservative therapy [52]. Surgery consisted of pubic symphysis resection, tricortical iliac crest autograft, and plate fixation. Return to play ranged from 5 to 9 months and all patients reported their pain had disappeared and no recurrences were noted at an average of 64 months postoperatively. No major complications were reported. Wedge resection alone of the pubic symphysis has been advocated by some [26, 50]. Grace et al. identified 10 patients with recalcitrant osteitis pubis in which wedge resection of the pubic symphysis was undertaken. While all 10 patients were able to return to their previous level of activities and all reported subjective decreases in pain in the short term, three patients continued to complain of groin pain and one patient had instability at the SI joint following their anterior Resection [26]. It should also be noted there have been reports of posterior instability following anterior wedge resection of the pelvis, resulting in arthrodesis of the SI joints [19]. While the use of bone graft with decortication of the pubic symphysis has been reported with good clinical outcomes in some series [52], it should be noted that series report that up to 30 % of patients may have evidence of hardware loosening with/without hardware failure [29]. Therefore, some authors advocate pubic symphyseal plate fixation with compression alone, finding no benefit or need of formal fusion [19, 53]. Rommens presented three patients in which conservative therapy failed following birth trauma, one of which included posterior instability/injury diagnosed on CT scan [49]. In all patients, anterior plating (with one patient receiving sacral bars) lead to resolution of pain and return to function [49]. In the specific case of osteitis pubis, there is some data to suggest that elite athletes operatively managed fair better and return to sport quicker than those treated conservatively [37]. In Paajanen et al.’s examination of eight patients treated operatively vs eight patients treated conservatively, all eight surgically treated patients had returned to their elite level of athletic competition at 1-year follow-up compared with only 50 % of those treated conservatively. In a separate evaluation, polypropylene mesh was placed in five patients with recalcitrant osteitis pubis [54]. All five patients were pain-free at one month and had returned to full activity by 1 year.

Numerous techniques for posterior fixation/fusion have been described. Buchowski et al. examined 20 patients in which a formal SI joint fusion via plating was performed through a Smith-Peterson approach [47]. Improvement in functional outcomes occurred in all patients after surgery. However, three nonunions occurred along with two deep infections, indicating the procedure is not without morbidity. Kibsgard et al. reported on open SI joint fusions (unilateral, bilateral, or with anterior plating) in which 84 % of patients had an underlying diagnosis of SI joint pain either secondary to pregnancy or “idiopathic” [55]. They noted no significant difference in functional outcomes between surgical and nonsurgical management with up to 23-year follow-up [55]. More importantly, long-term outcomes trended toward outcomes seen at 1-year follow-up, highlighting that recovery may progress for up to 1 year post surgery with little improvement after that time. Some authors have suggested percutaneous screw fixation alone is sufficient to limit motion as opposed to formal fusion with good clinical results [23, 53]. Van Zwienen et al. described their technique of anterior plating (either with or without wedge iliac crest grafting) along with posterior percutaneous screw placement in a cohort of 58 patients with postpartum pelvic pain [23]. In their series, statistical improvement in functional outcome was found at 12 and 24 months. Improvements from 20 wheelchair-bound and eight bed-bound patients fell to four in each group, respectively. However, 30 % of patients improved less than ten points in the Majeed score. Recently, hollow screws filled with bone graft have been utilized in a percutaneous fashion to treat SI joint pathology, including pelvic dysfunction and instability [56–58]. Improvements were seen in 87 % of patients utilizing validated outcome questionnaires with minimal complications [56]. In the patient with acute birth trauma and pelvic ring disruption, surgical decision-making should follow that of pelvic ring trauma. As these injuries are almost universally open book (anterior-posterior compression injuries), fixation of the anterior pelvis with or without sacral fixation is warranted. External fixation is typically reserved for patients who present immediately postpartum as the anterior approach/Pfannenstiel incision can cause significant bleeding secondary to venous engorgement within the space of Retzius immediately postpartum.

Surgical Technique

The treatment of both osteitis pubis and pelvic instability involves, essentially, the limitation of motion/movement at the pubic symphysis and the SI joint to allow healing and scarring and prevent pathologic motion. As such, both conditions are surgically treated similar.

The patient is placed supine on a radiolucent table to allow for ease of intraoperative fluoroscopy. A stack of towels or sheets is placed under the lumbar spine to slightly elevate the patient off the bed to allow increased access to the posterior buttock region. If percutaneous SI screw placement is planned, routine use of non-sterile neuromonitoring is recommended. A Foley catheter is always placed to deflate and protect the bladder. Preoperative antibiotics are administered. The abdomen is prepped cranially to the nipple line, caudally to just above the base of the penis in males or above the labia in females, and as posterior on the buttock as can be safely obtained, as can be seen in Fig. 3. A standard Pfannenstiel incision is then made approximately one fingerbreadth above the pubic symphysis centered on midline. Dissection is carried down to the rectus abdominis musculature and the linea alba. Care is taken to not stray too far lateral in the incision for fear of injuring either the inferior epigastric vessels or round ligament/spermatic cord. Once midline is identified, a split is made within the rectus abdominis musculature vertically and blunt dissection is taken to the space of Retzius. Often, significant scarring/adhesions are noted along the posterior aspect of the pubic symphysis from chronic, abnormal motion, and care should be taken to release/protect the bladder during dissection. A malleable retractor with wet sponge is placed to protect the bladder once mobilized. Dissection is carried along the superior border of the pubic symphysis to the pectineal eminence. Anteriorly, the rectus abdominis may be released to gain visualization if necessary. Figure 4 demonstrates the radiograph of a patient with osteitis pubis along with the initial dissection down to the pubic symphysis, looking onto the superior aspect of the pubic symphysis. Often, osteophytes can be identified (Fig. 5) and gross motion appreciated at the pubic symphysis without taking down any ligamentous structures. In addition, gross motion may be appreciated. The pubic symphysis is cleaned of debris/scar tissue followed by reduction with a large Weber clamp placed either within the obturator foramen or just inferior to the pubic tubercle. Care should be taken when placing this clamp as bone quality of the patient may cause clamp cutout if not careful. If formal fusion is deemed necessary, tricortical iliac crest graft harvest may be performed in the standard fashion for structural support. This may be either placed into the pubic symphysis or inlaid along the superior aspect with fixation placed over the top [52]. Figure 5 demonstrates an example of wedge resection of the pubic symphysis followed by placement of graft material. Once the pubic symphysis is reduced and compressed, either a 4- or 6-hole 3.5 mm reconstruction plate or pre-contoured pubic symphysis plate is chosen and placed (Fig. 4). Dual plating may be performed if necessary for (a) poor bone quality or (b) to aide and hold reduction in cases of chronic instability/deformity. Intraoperative fluoroscopy can confirm both reduction of the symphysis and plate/screw placement. The Foley catheter is checked for any signs of blood and to assure that urine output has occurred since closing down/reducing the pelvis to confirm no bladder injury or incarceration. The wound is lavaged and a deep drain is placed within the space of Retzius. The rectus abdominis muscle layer is closed followed by the skin.

Fig. 3

Standard prep and drape for an anterior approach to the pubic symphysis as well as percutaneous screw placement of the SI joints. Feet are located to the right, the head to the left

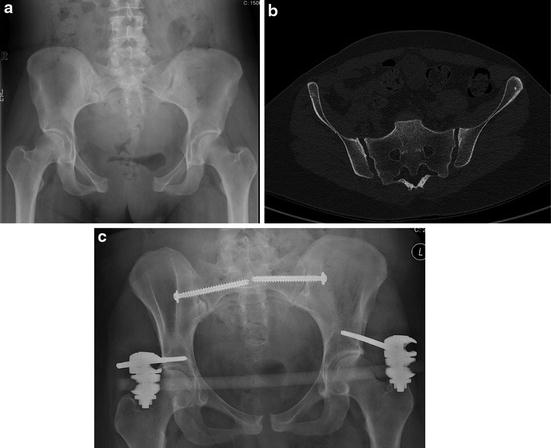

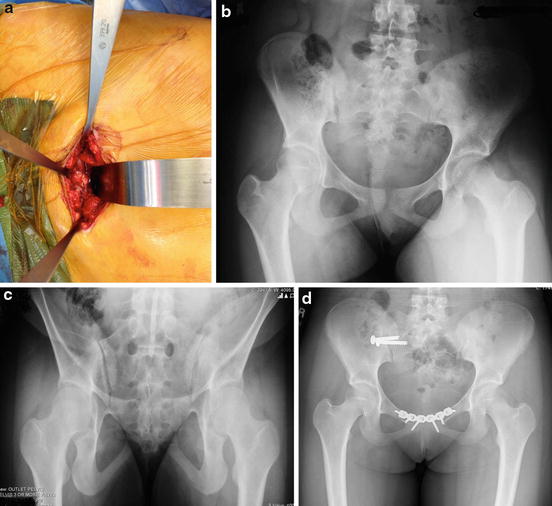

Fig. 4

(a) Radiograph of a patient with classic signs of osteitis pubis. (b) Dissection down to the superior and anterior border of the pubic symphysis. The patient’s feet are to the left of the image and the head to the right. (c) View of the pubic symphysis after wedge resection. In this case, the patient was bone grafted with iliac crest. Note the malleable retractor posterior to the pubic symphysis protecting the bladder. (d) Placement of 3.5 mm reconstruction plate with drilling

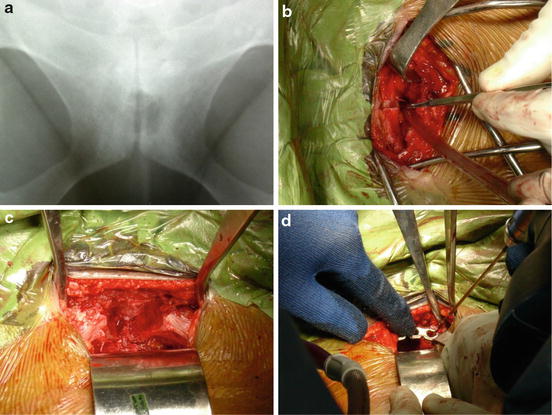

Fig. 5

Intraoperative photo of a 14-year-old with long-standing pelvic pain and instability after being hit into the perineum from a teeter-totter. Pain was located both anteriorly within the groin and posteriorly with feelings of “moving.” (a) Gross motion was identifiable at the pubic symphysis along with osteophytes about the superior pubic ramus. (b) Due to preoperative planning, the patient’s sacrum was quite dysmorphic on both the AP and outlet view (b, c) and would not safely allow screw passage into either S1 or S2. Smaller screws were placed across the SI joint along with anterior plate fixation (d) with resolution of the patient’s feelings of instability and pelvic discomfort at latest follow-up

The use of external fixation may be considered for anterior stabilization in certain cases. Given the reliability and track record of anterior plate fixation, external fixation is now primarily used in the setting of acute postpartum trauma in which a Pfannenstiel incision could result in increased risk of bleeding secondary to venous congestion within the space of Retzius. If an external fixator is placed for this indication, it is typically removed within 4–6 weeks after close radiographic follow-up of no changes to the overall pelvic ring.

If the patient requires posterior pelvic ring stabilization as deemed necessary by preoperative evaluation, the surgery continues with placement of SI joint screws. This can only be performed if adequate visualization of bone landmarks can be assessed on AP, inlet, outlet, and lateral radiographs intraoperatively and is often checked prior to prep and drape not only to assure visualization but also to mark out these angles to save time intraoperatively (inlet/outlet study). This technique should not be undertaken by those who have not been trained in placement of percutaneous SI joint screws. Preoperative planning and review of the patient radiographs and CT scan are critical to assess for safety of screw placement and corridors [59–61]. S1 or S2 screws may be used to “lock” the SI joint. These screws are placed as a true “SI joint” screw (posterior-to-anterior and often caudal-to-cranial direction as dictated by preoperative planning) as opposed to a “straight across” sacral screw. Often, two screws are used to help control rotation about the SI joint if patient anatomy allows and is deemed safe. Guide pins are placed utilizing the inlet (used for assessment of anterior-posterior pin placement), outlet (used for assessment of cranial/caudal placement in relation to the sacrum and the neuroforamen), and lateral (used to confirm pin placement within the body and no cortical perforation anteriorly) projections. The pin is then measured with a pre-calibrated measuring depth gauge. A cannulated drill is then used to drill over the pin, and the measured screw is then placed under fluoroscopy and confirmed to be in adequate position in all planes. The wounds are then closed in standard fashion. Figure 6 demonstrates an example of anterior plate fixation followed by percutaneous posterior pelvic fixation. Two screws were used posteriorly to help control rotation of the SI joint. If a formal fusion of the SI joint is deemed necessary, the patient is positioned similar to the above. The lateral window of the ilioinguinal approach is undertaken with skin incision following the level of the iliac crest. Dissection is carried down to the intermuscular and sharply defined plane between the gluteus maximus muscle and external abdominal oblique muscle. With use of knife or electrocautery, the external oblique and abdominal muscles are taken off the iliac crest from the level of the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) working posteriorly. Incision distal to the ASIS will help relax skin tension and allow better access to the SI joint. The iliacus muscle is then easily dissected bluntly from the inner table/iliac fossa of the acetabulum and packed with lap sponges. Bone wax should be readily available for any bone bleeders of significance. Dissection is carried back to the SI joint, and retractors can be placed medial to the joint into the sacrum. Care should be taken to not travel too medial onto the sacrum as the L5 nerve root lies within 1–2 cm of the SI joint. Curettage and debridement of the SI joint is then undertaken and bone graft placed. Typically, two 3.5 mm recon plates, placed at 90° to one another, are then used to secure the iliac wing to the sacrum. This can be further stabilized by placement of an SI screw as described above. Figure 7 demonstrates an example of formal SI fusion with this technique.