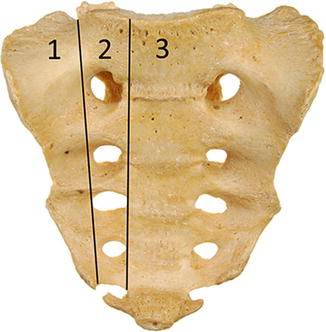

Fig. 1

Model of femur demonstrating where a tension or compression fracture of the femoral neck would occur

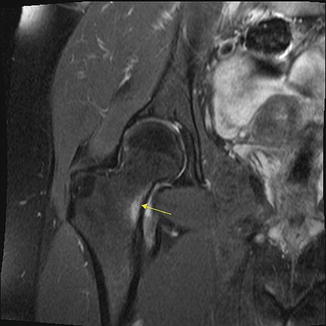

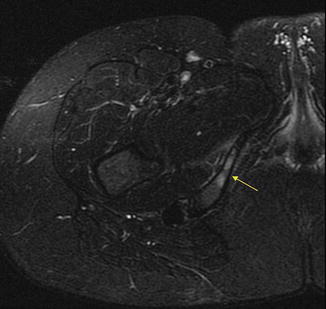

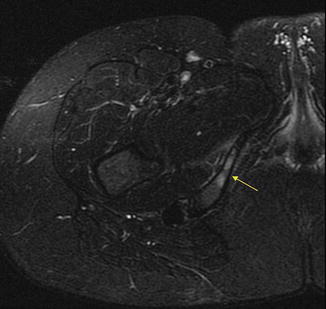

Fig. 2

Compression side femoral neck stress reaction (arrow) is noted on coronal proton density fat-saturation MRI image

A detailed history including activity level and any recent changes in training or exercise regimen should be elicited. In females it is helpful to obtain a menstrual history. On physical exam, a patient may have an antalgic gait. Swelling and erythema are usually absent. Clinical assessment should also include leg length discrepancies, leg alignment, or presence of pes planus or cavus. Due to the deep structure, it may be difficult to elicit bony tenderness with palpation. There may be pain with flexion and internal rotation of the hip. Special tests may also be positive such as hopping on the affected side or fulcrum test. Obtaining plain radiographs prior to more dynamic tests may avoid potential worsening or displacement of the fracture at the time of testing.

Once the diagnosis of a femoral neck stress fracture is determined, serial radiographs can be used to monitor for displacement and progression of healing. If displacement is seen, the patient should be taken for emergent surgical stabilization. Avascular necrosis has been reported to occur in 25–30 % of patients with displaced femoral neck fractures treated with internal fixation [39]. Overall prognosis of nondisplaced femoral neck fractures seems to be very good. In a Finnish study of military recruits, 66 patients with 70 femoral neck fractures were followed for a mean of 18.3 years. None of these military recruits had any signs of osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis at follow-up [33].

Stress Fractures of the Pelvis

Pelvic stress fractures have been well described in long distance runners and military recruits. However, it is not uncommon to see older patients with pelvic insufficiency fractures. It has been estimated that pelvic stress fractures account for 1–7 % of all stress fractures [40]. The most common pelvic bone to be fractured is the inferior pubic ramus [41]. Having a concomitant pelvic fracture such as an acetabular or pubic ramus fracture has been seen in up to 25–80 % of pelvic stress fracture cases [42].

Sacrum

Stress fractures of the sacrum should be considered in individuals with insidious onset of asymmetric low back pain or buttock pain. Patients most commonly present with lumbar back or gluteal pain, although hip, groin, and radicular type pain have also been reported. Symptoms are usually worsened with weight-bearing activities and relieved with rest. Sacral stress fractures are often misdiagnosed as the history and physical exam can be suggestive of more common etiologies such as spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, piriformis syndrome, lumbago, vertebral compression fractures, or spinal stenosis.

Denis et al. classified sacral fractures into three zones (Fig. 3) [43]. Zone 1 involves the sacral ala or wing and is the most common part of the sacrum to sustain a stress fracture. Zone 2 extends from the sacral foramina to the sacral body. Fractures in zone 2 can result in unilateral lumbosacral radiculopathies. Fractures in zone 3 involve the sacral body or canal of the sacrum. Fractures in zone 3 can cause bilateral neurological symptoms, saddle anesthesia, and sphincter tone dysfunction.

Physical exam may reveal sacral tenderness with palpation which is a nonspecific finding. The patient may have pain with the flexion-abduction-external rotation (FABER) test or Gaenslen’s test. The FABER test is performed by flexing the hip of the affected side to 90°. The examiner then places the hip in external rotation while pushing the knee on the affected side toward the exam table. The Gaenslen’s test is done with the patient lying supine with the knee on the affected side fully flexed with the contralateral leg dangling off the exam table. The examiner then simultaneously applies flexion to the affected hip while hyperextending the contralateral side. The test is positive if pain is elicited. Having the patient hop on the leg of the affected side might also elicit pain. About 70 % of patients may complain of neurologic symptoms that suggest a radiculopathy or myelopathy; objective neurological findings may only be found in 2–14 % of cases [42]. In the rare case where the fracture involves the sacral body, neurologic symptoms such as sphincter tone dysfunction or limb paresthesias can be found. Careful attention should also be put into examining the pubic rami. As discussed above, there is an association of concomitant pelvic stress fractures. One study found that 78 % of patients with a sacral stress fracture also had a coexisting pubic ramus fracture [44]. Disruption of the pelvic ring can cause increased stress in other areas and may be the reason why concomitant pelvic stress fractures occur.

Fractures are usually found in the sacral ala (Fig. 4) and run parallel to the sacroiliac joint [42]. Radiographs are of limited utility as stress fractures in this area may be obscured by the presence of stool, bowel gas pattern, and calcified vessels. Bilateral sacral fractures may be seen and in some cases can be connected by a horizontal fracture through the sacral body creating the so-called H sign which can be seen on bone scintigraphy. The presence of the “H sign” has been reported to be highly specific for an insufficiency fracture [45].

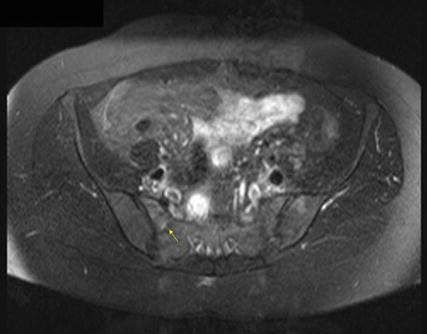

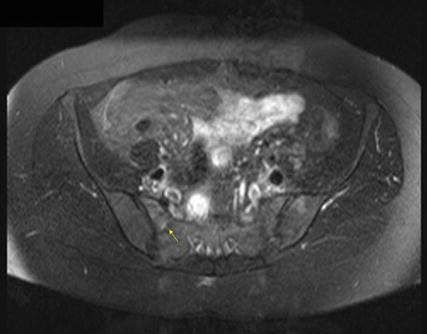

Fig. 4

Right sacral ala insufficiency fracture. T2 axial fat-saturation MRI reveals abnormal bone marrow edema (arrow)

Pubic Ramus

Pubic ramus fractures account for 1.25 % of all stress fractures [46]. Most pubic ramus stress fractures occur at the medial portion of the pubic ramus or at the junction between the inferior pubic ramus and the ischial ramus (Fig. 5) [47]. The adductor magnus muscle originates at this junction, and its repetitive contraction has been attributed to contribute to the development of a pubic ramus stress fracture [46]. Patients often complain of insidious onset of groin pain but can also present with perineal, anterior thigh, or buttock pain. On physical exam there may be direct tenderness to palpation over the pubic ramus. There may also be an antalgic gait, pain with abduction, or pain with resisted adduction and external rotation of the hip.

Fig. 5

MRI T2-weighted sequence of a right inferior pubic ramus stress fracture

General Diagnostic and Treatment Guidelines

In most cases, radiography should be the first diagnostic imaging obtained. If the radiographs do not demonstrate a stress fracture and the diagnosis is still suspected, an MRI can be obtained as it is highly sensitive in detecting stress fractures, does not subject the patient to ionizing radiation, and can give valuable information on surrounding soft tissue structures. Alternatively, another acceptable option is to obtain serial radiographs as findings are often not seen initially and may become apparent a few weeks after the onset of pain. Serial radiographs may also be useful in monitoring healing once the diagnosis has been established. Although not typically needed, repeating an MRI can be done to assure that the stress fracture is healing or has healed. A clinical example where repeating an MRI may be useful is in a patient with persistent pain despite treatment. The presence of stool, bowel gas, and calcifications of vessels on radiographs can make it difficult to see pelvic stress fractures. In this case, a repeat MRI can be done to monitor for healing of a sacral stress fracture.

The first step to treating a stress fracture should involve pain control. Medications, activity modification, and immobilization can help control pain. A variety of medications can be considered based on the patient’s reported pain level. These include acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and narcotics which are typically not needed. Some studies suggest that the use of NSAIDs should be avoided in management of fractures due to risk of delayed union or nonunion [48, 49]. However, a meta-analysis in 2010 did not find any significant risk of nonunion with NSAID use [50]. When considering the use of NSAIDs for pain control in stress fracture management, the treating physician should carefully consider the current scientific literature regarding its use in fracture healing.

Treatment plans should be tailored to each patient. In general relative rest and partial or full non-weight-bearing status should be implemented if significant amount of pain is present. The patient should avoid any aggravating activities and gradually increase activity as directed by the treating clinician when pain-free. In some cases low impact exercise such as stationary cycling or swimming may be appropriate. Physical therapy should be initiated when the patient is without significant pain. Once the patient is pain-free with normal daily activities, a graduated progressive plan back to sports can be initiated. If bed rest is chosen, deep vein thrombosis prevention and early mobilization, when appropriate, should be the goal. In general, total rehabilitation time can take 4–8 weeks.

Summary

Stress fractures are a common occurrence especially in female athletes. However, stress fractures of the hip and pelvis are relatively rare events and can be difficult to diagnose. The cause of these injuries is multifactorial and includes intrinsic and extrinsic factors such as the female athlete triad and biomechanical, anatomical, training, and nutritional factors. The clinician should maintain a high level of suspicion especially in young female athletes that display even part of the female athlete triad to prevent delay in diagnosis. Most hip and pelvic stress fractures can successfully be treated conservatively. Early rehabilitation should be implemented to return patients to their prior level of activity as soon as medically possible. It is important to have a good knowledge base about the causes of stress fractures as this can aid in its prevention and other overuse injuries.

References

1.

2.

Frost HM. Some ABC’s of skeletal pathophysiology. 5. Microdamage physiology. Calcif Tissue Int. 1991;49:229–31.PubMedCrossRef

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree