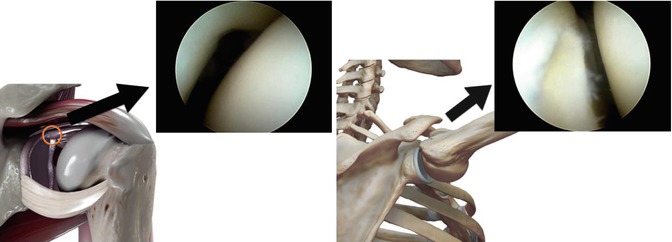

Fig 11.1

The mechanisms of injury

Chronic SLAP tears from repetitive microtrauma are commonly seen in overhead sporting activities [6]. The pathophysiology of chronic SLAP tears has been much debated, and various mechanisms have been proposed. All these mechanisms are centered around a repetitive overhead motion of hyperabduction and external rotation, which produces large forces and increased shear and compression forces on the glenohumeral joint and strain on the rotator cuff and capsule-labral structures [5]. One of the suggested pathophysiology is alteration in the kinetic chain. Throwing requires a complex series of coordinated motions resulting in the transmission of large forces from the legs, the core, via the shoulder, onto the arm and hand. If such coordinated effort of the “kinetic chain” is altered, such alteration can lead to abnormal forces, leading to injury to the labrum or the rotator cuff [11]. An overhead athlete is particularly predisposed to such alterations due to the “thrower’s paradox,” i.e., a thrower must possess sufficient laxity to allow excessive external rotation, yet sufficient stability to prevent glenohumeral joint subluxation [15]. It is commonly noted in overhead athletes that the range of external rotation is increased and the internal rotation is correspondingly decreased [2]. This pattern is termed as glenohumeral internal rotation deficit or GIRD. Such changes, although advantageous to an elite training athlete, may predispose the athlete to labral injuries (Fig. 11.2).

Fig 11.2

Image showing a muscle model in the extreme overhead position of a baseball pitch, with arching of the back and hyperextension of the shoulder. Kinetic chain – throwing requires a complex series of coordinated motions resulting in the transmission of large forces from the legs, the core, via the shoulder, onto the arm and hand

Another patho-mechanical explanation of a chronic SLAP tear may well be as a result of contracture of the posterior shoulder capsule, resulting in a relative posterior superior migration of the humeral head [5]. Such a posterior contracture appears with repetitive overhead external rotation and can result in a secondary posterior superior position of the humeral head. This, in turn, increases the shear forces across the glenohumeral joint, leading to internal impingement. Burkhart et al. [5] also described the “peel-back” mechanism, which may potentially explain chronic SLAP tears. During the abduction and external rotation of the shoulder, torsional forces in the biceps and labrum increase as the arm moves to this extreme position, leading to a twist at the base of the biceps, which transmits such a force onto the labrum, resulting in a “peel back.” Furthermore, in athletes with such altered mechanics of posteroinferiorly contracted capsule, a “peel-back” mechanism is exacerbated if the position of the scapula is protracted and laterally rotated (Fig. 11.3).

Fig 11.3

The peel-back mechanism in a throwing athlete with tight posterior capsule

It is likely that all the above mechanisms have a role to play in the pathophysiology of the chronic SLAP tear seen in an overhead athlete. Snyder et al. [14] developed an arthroscopic classification for SLAP tears, which is common to both acute traumatic SLAP tears and chronic SLAP tears caused by repetitive micromotion. Various modifications to the original SLAP classification by Snyder et al. [14] have been proposed, notably type 5, where a Bankart lesion extends into the superior labrum and biceps anchor, and type 8 with a posterior labral extension into a 6 o’clock position. Such type 5 and type 8 lesions are commonly seen in acute SLAP tears, resulting from a concomitant shoulder dislocation, as indeed the type 9 (more severe labral tears with circumferential involvement). SLAP tears, in contrast, as a result of chronic repetitive overhead motion, would classically lead to a type 2 SLAP tear. Such type 2 SLAP tears have been further classified into type 2A, B, and C [13]. The most frequent lesion seen in chronic SLAP tear is a type 2B SLAP tear.

11.3 Clinical Presentation and Physical Examination

Patients presenting with an acute SLAP tear give a history of sudden onset pain following an episode of fall, traction force along the arm, a throwing action, or a dislocating force. They commonly report pain in the anterior aspect of the shoulder and describe this as “deep.” This pain can sometimes be associated with a click and is commonly exacerbated by forward flexion and internal rotation and recreation of the throwing action. The athlete commonly reports sudden pain, a popping sensation, and loss of function.

Chronic SLAP tears resulting from repetitive overhead action commonly present with insidious onset pain, which is usually noted at the time of abduction, external rotation, or the late cocking phase of throwing. Such symptoms are usually located along the biceps tendon or posterosuperiorly. However, overhead athletes may report a “dead arm” [11] with a loss of power during throwing. Patients may also present with rotator cuff insufficiency, especially in internal impingement, where rotator cuff tears are commonly associated with such SLAP tears.

Physical examination begins with assessment of core stability, scapular kinematics, and assessment of range of motion. A glenohumeral internal deficit (GIRD) should specifically be sought, and tests for shoulder instability and rotator cuff strength should be performed. A wide variety of physical examination techniques have been described to clinically diagnose SLAP tears. Such tests include the O’Brien’s active compression test, anterior slide test, biceps load test, dynamic labral shear test, and labral tension test. None of these tests, however, are diagnostic of SLAP tears, either as stand-alone or in combination [12] (Figs. 11.4 and 11.5).

Figs. 11.4 and 11.5

Assessment of gird – see here – https://www.dropbox.com/s/kbdfkijx3qgg9y3/GIRD%20swimmer.wmv. O’Brien’s test: resistance is tested with the arm forward flexed to 90° and adducted 10° with the thumb pointing down (a) and subsequently with the thumb pointing up (b)

11.4 Imaging

The gold standard for diagnosing a SLAP tear, acute or chronic, remains MRI arthrography. In this technique contrast is injected into the glenohumeral joint under radiographic control and leads to controlled distension of the glenohumeral joint. Seepage of contrast under the labrum is confirmatory of a SLAP tear. It has been suggested that MRI arthrography in the ABER (abduction, external rotation) position can recreate the posterior superior labral “peel back,” hence increasing the detection of SLAP tears [4]. It is, however, extremely important that the findings of such sensitive investigations are interpreted and analyzed with caution. It is not uncommon for athletes to have MRI abnormalities [9]. Clinical correlation of MRI arthrography should be carried out alongside the clinical findings to avoid overdiagnosis of such lesions as the presence of sublabral recess can lead to false-positive reports.

Although standard radiographs are not useful in diagnoses of SLAP tear, they are commonly performed to exclude associated bony injuries and concomitant pathology such as A-C joint disease, fractures, and extrinsic subacromial impingement (Fig. 11.6).

Fig. 11.6

MRA of SLAP in neutral and ABER position

11.5 Arthroscopic Pathology

The surgeon should be aware of the common anatomical labral variance of the superior sublabral recess, sublabral foramen, and Buford complex [10] in order to avoid false-positive diagnosis of SLAP tears. The Snyder classification for SLAP tears is commonly used to describe superior labral tears, with the essential pathology being disruption of the superior labral tissue from the underlying hyaline cartilage. Acute SLAP tears are commonly type 2, type 5, type 8, or type 9. However, all forms of labral injury can be associated with such acute traumatic labral tears. Chronic SLAP tears are commonly associated with type 2B lesions. The superior labral lesions as a result of overhead repetitive activity commonly appear frayed. Such chronic tears may well be associated with partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. It is useful to perform intraoperative “peel-back” mechanism where the arm is taken into a position of abduction and external rotation and the superior labrum closely observed for instability. This maneuver is useful in demonstrating the labrum peeling off the posterior superior aspect of the glenoid. Visual demonstration of “peel back” leading to exposure of the underlying glenoid bone would prompt the surgeon to perform labral repair [5]. A systematic examination of the joint should also include examination of the rotator cuff, the rest of the labrum, and, in particular, the status of the biceps tendon (Figs. 11.7 and 11.8).