identified and added, or some goals, which become irrelevant or unachievable, are eliminated.

TABLE 13.1 Rehabilitation Team Members Associations, Organizations and Journals as of April 2008 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 13.2 McGregor’s Characteristics of an Effective Work Team | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

built-in feedback mechanism through which it constantly monitors itself and maintains its effectiveness. When a team is not functioning well, effective function can be developed or restored through the process of team building (6). Team building requires commitments of time and energy, but the rewards of improved patient outcomes and satisfaction of the team members are worth the effort (6, 10, 11).

Show/teach team members how to work together and provide sufficient practice time in teamwork.

Ensure that all members learn, understand, and respect the knowledge and skills of others.

Develop clear definitions of the roles and behaviors expected of team participants and lessen ambiguities regarding expectations of others.

Encourage use of the full potential of each member.

Direct attention to initiation and maintenance of communication and to the breaking down of barriers to interdisciplinary communications.

Attend to the maintenance of the teams in the same way that other organizations engage in activities that strengthen their cohesion and offer satisfaction to their personnel.

Acknowledge that leadership should shift as necessary in terms of the patients’ needs.

Ensure that the person in the leadership role respects the other members, as evidenced by consultation, active listening, and their inclusion in planning.

Develop an internal system for demonstrating the accountability of each team member to the group, as well as to the institution in which the team practices.

Develop a process to acknowledge conflict as it arises and to address it in a manner that strengthens the group and its members.

TABLE 13.3 Personal Characteristics of Successful Interdisciplinary Team Participants | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

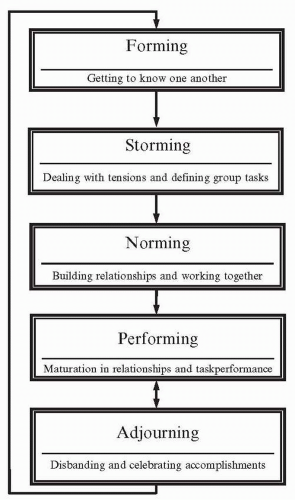

During the forming stage, initial entry and identification with the group are the primary concerns. Group members are interested in what the group can offer them and what they can offer the group. During this stage, individuals are usually on their best behavior and may temporarily overlook conflicts for the good of the group.

Storming is the most difficult stage and is characterized by high emotional tension. The level of trust becomes low during this phase. Team members tend to pressure the rest of the group to accept their preferences. Status and control in the group may become an issue during this phase. Cliques and coalitions may form here, and “hostility and infighting” (14) are common. During this phase, members begin to understand one another’s interpersonal styles and learn to interact within those parameters (15). Team members also attempt to find ways to work toward the team’s goals while they seek concurrently to meet their individual needs.

The norming phase is a transition to more comfortable and stable interaction and is referred to as initial integration. Balance begins to emerge during this phase, and the team begins to function more as a unit. This initial balance is not completely stable and can give way at any time, but balance and focus are usually reestablished fairly quickly. The newfound harmony usually comes as a great relief after the storming and may become the primary objective of the team for a period of time. Trust improves; however, the group has not yet matured, and the balance between group needs and individual needs is precarious.

Performing, also referred to as complete integration, is characterized by maturity and a high level of functional efficiency. Complex tasks and disagreements no longer suspend or preoccupy the group. They are quickly resolved, often creatively, and the group moves on toward goal accomplishment. Trust is a key component of the successful team and becomes very high during this phase.

The adjourning phase occurs when the team disbands. The ability to do this and reconvene in the future as needed is the true test of a team’s integration, maturity, and ultimate success.

FIGURE 13-2. Phases of new team development. (Modified from Schermerhorn JR, Flint JG, Osborn RN. Organizational Behavior. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: John Wiley & Sons; 2000:178-181.) |

phases, extra care needs to be taken to avoid the appearance of selling out for personal gain during this time of naturally high distrust. Emphasizing the value and importance of each member will help to establish trust and facilitate progress through these tumultuous phases of team development.

TABLE 13.4 Some Qualities of a Leader | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

Autonomy

Individual members’ personal characteristics that may contribute to personality conflicts

Role ambiguity

Incongruent expectations

Differing perceptions of authority

Power and status differentials

Varying educational preparation of the patient care team members

Hidden agendas

All parties must agree to come together and work on the problems.

Members must agree that there are problems that need to be solved and that solving them is everyone’s responsibility.

Members accept the position that the end result is that the team will communicate better, thus enhancing the rehabilitation process (6).

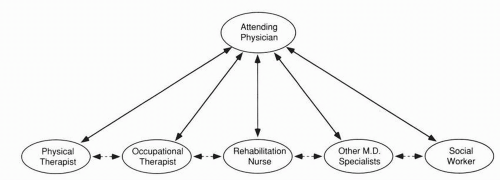

patient as determined by the attending physician. The quality of the service rendered by the consultant, and thus future consultations, depends on meeting the needs of the patient and the attending physician. The consultant identifying additional needs would usually discuss them with the attending physician before proceeding with the additional treatment, in recognition of the fact that the attending physician may have additional information and insight not available to the consultant. This traditional system results in a clear chain of responsibility that continues to be well respected and is reinforced medicolegally. This traditional autocratic model of leadership, in which the physician assumes an authoritarian role and other team members obey, is not effective in the rehabilitation setting (10). Multiple consultations may result in many professionals doing multiple tasks. Coordination of these efforts by the attending physician or among the involved professionals can often be difficult or incomplete, resulting in less efficient and sometimes redundant patient care. This is one of the major disadvantages to the medical model of patient care (21, 23, 27).

FIGURE 13-3. Multidisciplinary team conference structure. Vertical communication (solid lines) may serve to limit horizontal communication (dotted lines) between team care providers. |

evolved from the medical model attending physician’s role and relationship with consultants (26).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree