Restrictions

Osteoplasty/rim trimming

Labral repair/reconstruction

Microfracture

Passive range of motion (PROM)

Extension to 0° × 21 days

Extension to 0° × 21 days

Extension to 0° × 21 days

External rotation to 0° × 17–21 days

External rotation to 0° × 17–21 days

External rotation to 0° × 17–21 days

Abduction 0–45 × 14 days

Abduction 0–45 × 14 days

Abduction 0–45 × 14 days

Flexion, adduction, IR no limits within pain-free range

Flexion, adduction, IR no limits

Flexion, adduction, IR no limits within pain-free range

Within pain-free range

Weight bearing (WB)

20 lb WB with crutches × 3 weeks, 50 % × 1 week, then wean gradually 10 %/day as tolerated until normal gait is achieved

20 lb WB with crutches × 3 weeks, 50 % × 1 week, then wean gradually 10 %/day as tolerated until normal gait is achieved

20 lb WB with crutches × 7 weeks, 50 % × 1 week, then wean gradually 10 %/day as tolerated until normal gait is achieved

Continuous passive motion (CPM)

6+ h/day at 10° abduction

6+ h/day at 10° abduction

8+ h/day at 10° abduction

Hip brace

Set at 0–105 used while ambulating × 21 days

Set at 0–105 used while ambulating × 21 days

Set at 0–105 used while ambulating × 21 days

Anti-rotational boots

Used while lying supine × 17–21 days, correlated to ER restriction

Used while lying supine × 17–21 days, correlated to ER restriction

Used while lying supine × 17–21 days, correlated to ER restriction

Protection of the repaired tissue is achieved through range of motion restrictions, weight-bearing status, hip flexor protection, bracing, and an anti-rotational system. Hip extension and external rotation are typically restricted initially because they place stress on the anterosuperior portion of the joint capsule. Many arthroscopic procedures enter the joint using two to three arthroscopic portals placed anterolateral, mid-anterior to the hip joint [2]. Depending on joint laxity, closure to the capsule or a plication of the capsule may be performed in order to increase hip joint stability. The duration of restriction is variable depending upon the severity of the joint closure and quality of ligamentous integrity. Supplemental protection may be provided by the use of a hip brace, which limits extension, external rotation, and abduction.

Patients are advised to use different options to sleep comfortably while maintaining postoperative range of motion restrictions. One, patients may either sleep in a device to limit external rotation or sleep in a constant passive motion machine (CPM), if it is prescribed, which maintains a neutral position of the hip. Sleeping on the uninvolved side offers the patient an alternative sleeping position while gravity restricts abduction and external rotation from occurring. Patients are encouraged to use a large pillow under the involved extremity to limit excess adduction and internal rotation, which is typically painful.

Weight-bearing restrictions may vary among surgeons, the surgical procedure, concomitant procedures, and/or comorbidities. A single-subject study assessing in vivo acetabular contact pressures during gait showed that touchdown weight-bearing (TDWB) produced the least amount of acetabular contact pressure when compared to full weight-bearing (FWB), partial weight-bearing (PWB), and non-weight-bearing gait (NWB) [3]. Patients who do not undergo microfracture of a weight-bearing surface are typically limited to TDWB for 2–4 weeks. One of the primary reasons of this limitation is to reduce joint effusion and tissue edema. Joint effusion of the hip triggers arthrogenic inhibition of the gluteus medius (GM) [4], which is essential for normal gait and pelvic control. In later phases of rehabilitation, recurrent or chronic joint effusion may continue to contribute to GM inhibition, leading to increased anterior joint forces during hip extension and gait [1, 5].

Reduction of Pain, Inflammation, and Fibrosis

Postoperative pain and inflammation are controlled through medication, use of a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine, early nonresistance biking, and soft tissue modalities. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDS), muscle relaxants, and pain medication may be prescribed by the physician. Ice compression devices are recommended 4–5×/day or as needed for pain control and inflammation during the first 2 weeks of recovery. Cryotherapy has been shown to be an efficacious modality with reducing the use of analgesic medication and pain while improving comfort with sleeping and overall satisfaction in postoperative patients [6, 7].

Range of motion is initiated as early as postoperative day (POD) 0. This includes early stationary biking without resistance for 20 min, twice daily to assist with portal drainage. Passive circumduction range of motion performed by a therapist or caregiver is recommended daily. The circular motion performed during this exercise encompasses flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction of the hip and is simple to instruct to caregivers. Additionally, it has been theorized to reduce adhesions about the zona orbicularis of the hip because of the circular motion.

Manual physical therapy techniques , such as lymphatic massage or gentle joint mobilizations (grade 1 and 2), can be used to decrease postsurgical inflammation and control pain. These techniques are performed for 2 weeks after surgery or until inflammation has dissipated. Soft tissue mobilizations to lengthen tissue and decrease reactive muscle tone surrounding the hip joint are then initiated. Anterior musculature, such as the iliopsoas, rectus femoris, tensor fasciae latae, and adductor muscles, tends to respond to surgery with reactive shortening and hypertonicity. This may be due to effusion and positioning the hip in flexion for prolonged periods of time, such as when using the CPM machine. Previous authors have recommended that patients lay in a prone position daily during phase 1 [8].

Restoring Passive and Active Ranges of Motion

Passive range of motion is initiated on POD 0 and continued through phases 1 and 2 or until full range of motion is achieved. Initially, flexion, internal rotation (IR), abduction (abd), adduction (add), and circumduction are performed to help restore mobility, prevent fibrosis [8–10], and contribute to joint health [11]. Abduction is restricted to 45° for the first 2 weeks, and external rotation and extension are typically limited to neutral for 2–3 weeks. These limitations prevent capsular stretching at the surgical site. Excessive flexion and IR should be avoided to limit irritation due to compression at the surgical site [9]. The frequency of passive range of motion is varied; however, twice daily is recommended.

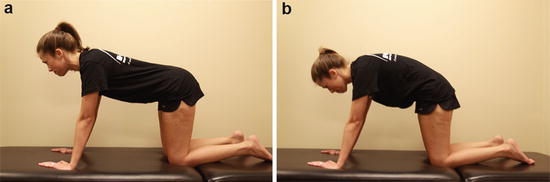

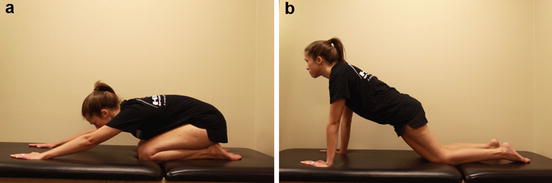

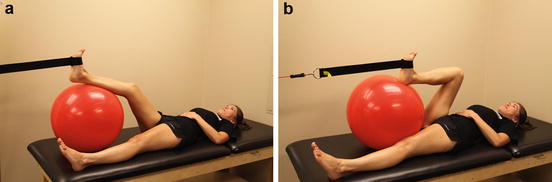

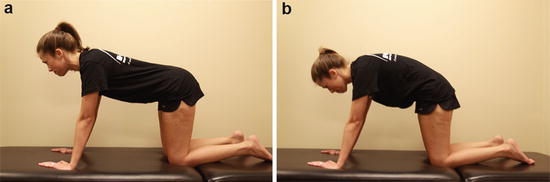

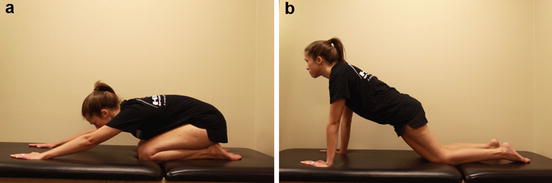

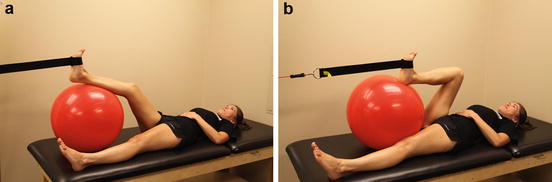

Active range of motion is initiated within the first week in order to promote neuromuscular control and normal muscle firing patterns. Exercises, such as cat and camel and quadruped rocking (Figs. 1 and 2), are initiated as early as postoperative day 4. These exercises are recommended to reestablish pelvic control through the stabilizing effect of co-contraction and recruitment of synergistic muscle groups. Quadruped rocking allows gravity-assisted hip flexion to occur while decreasing the pinching sensation a patient may experience in supine flexion. Hip flexor activity is typically limited during the initial 2 weeks of rehabilitation to avoid magnifying anterior hip pain. During week 3, patients may begin light, pain-free hip flexion exercises. Patients and therapists should be aware of compensation patterns, increased irritation of rectus femoris, hip adductors, and tensor fasciae latae (TFL) muscles and tendons; these muscles tend to substitute for iliopsoas weakness or inhibition [1, 12]. Figure 3a, b demonstrates such an exercise. During this exercise, the patient lays supine while rolling a fit ball into hip flexion and extension while maintaining trunk control. This can be performed with (as pictured) or without light resistance.

Fig. 1

(a and b) Cat and camel exercise. The patient assumes a quadruped position and performed lumbar flexion and extension and pelvis anterior and posterior rotation. This creates a hip flexion and extension moment while promoting gentle neuromuscular control in a closed kinetic chain

Fig. 2

(a and b) Quadruped rock exercise. The patient assumes the quadruped position and performs a gentle rocking motion forward and backward as tolerated. This exercise is an excellent exercise for patients to perform unassisted range of motion and gentle stretching of flexion and extension at home while promoting neuromuscular control of the hip, pelvis, and trunk

Fig. 3

(a and b) Supine hip flexion. This exercise is performed in a supine position with the involved extremity on a fit ball. As the patient stabilizes the trunk, active hip flexion and extension are performed to encourage light activity of the hip flexors and normal movement patterns. Resistance may be added to this exercise as pictured above

Proper Neuromuscular Control Patterns

A key component to prepare the hip joint for weight-bearing and normal gait is reestablishing proper neuromuscular control patterns of the hip. Patients with FAI and labral pathology often develop compensation patterns of the hip, trunk, and lower extremity. These patterns continue after surgery has been performed, which may be harder to correct the longer they have been present. Common patterns that occur prior to surgery include:

Hypertonic muscles

Iliopsoas

TFL

Adductors

Piriformis

Inhibited/hypotonic muscles

Gluteus medius

Gluteus maximus

Deep external rotators

In order to restore normal muscle activation, the musculature of the hip, trunk, and lower extremity must be addressed simultaneously. Initially, patients are instructed on isometric exercises that recruit the GM, GMax, quadriceps, hamstrings, and transverse abdominus. Patients are instructed to co-contract trunk musculature with hip and lower extremity musculature in order to promote trunk and pelvic stability.

As swelling and pain decrease, open chain, active assist, and active exercises are initiated with the goal of recruiting inhibited muscles and reducing activity of hypertonic muscles. Three studies have looked at rehabilitation exercises that target gluteal musculature while minimizing hypertonic musculature [13–15]. Selkowitz et al. [13] studied gluteal-specific exercises that reduce TFL activity. Philippon et al. [14] ranked 13 hip exercises in order of GM iliopsoas activity. In a similar study, Giphart et al. [15] ranked the same exercises with regard to gluteal piriformis and pectineus activity. While some exercises in these studies will reduce, for example, TFL activity, they may increase the activity of other muscles, such as the iliopsoas, pectineus, and piriformis. Therapists should use these exercises in the presence of hypertonicity of the specific muscles identified during a patient assessment.

Active assisted exercises include the slide board abduction exercise and can begin during the first postoperative week. Once gluteus medius isolation is mastered with slide board abduction, the patient can progress to standing abduction, and side lying gluteus medius holds. It is important to be aware of TFL substitution during these exercises. Early activation of the deep external rotators can begin week 2 with prone external rotator activation from the position of IR and stopping at neutral. This will activate the rotator muscles with respect to the ER rotation restriction. Furthermore, gluteus maximus activation and transverse abdominis stability can be progressed from an isometric exercise to quadruped hip extensions (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Quadruped hip extension. The patient assumed quadruped position and then extends the involved leg into hip extension. Careful attention should be placed on compensation patterns such as excessive lumbar lordosis and anterior pelvic tilting. The patient is instructed to recruit trunk musculature in order to counteract these compensatory patterns

Criteria to Advance to Phase 2

Criteria to advance to phase 2 include (1) minimal pain with all phase 1 exercises, (2) correct muscle firing patterns with all phase 1 exercises, and (3) minimal complaints of anterior hip pain prior to 100° of passive hip flexion.

Phase 2

Phase 2 begins when weight-bearing restrictions have been discontinued and phase 1 criteria have been met. The main goal of phase 2 is to restore normal gait. Secondary goals include returning the patient to weight-bearing activities of daily living, ascending and descending stairs with alternating gait, and double-limb squatting. Phase 2 may be considered the most critical phase to success after hip arthroscopy because of the neuromuscular challenges the rehabilitation specialist will encounter when returning a patient to unrestricted weight bearing. As patients progress to walking without an assistive device, they are more likely to experience increased anterior hip pain, which is commonly described as hip flexor tendonitis [8, 16]. This pain may be better explained as excessive anterior hip forces on the surgical site created by the femoral head due to insufficient muscle activity during hip extension and flexion motions. This pain may be difficult to control without rest and unloading of the joint until the pain subsides.

Gait Progression

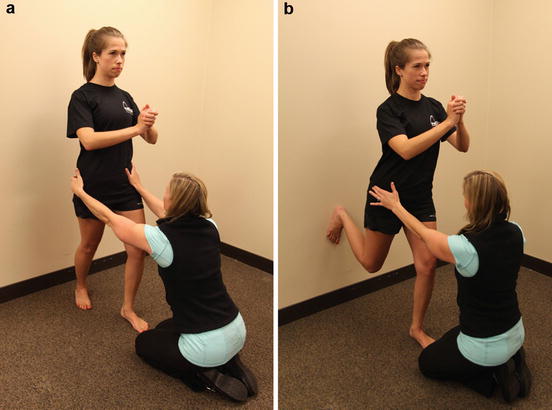

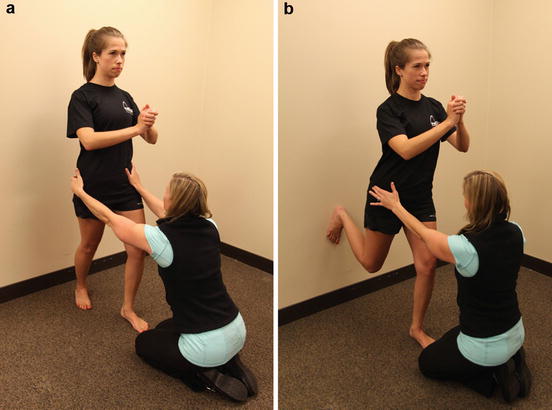

Weaning a patient from assisted weight bearing to full weight bearing should be progressed carefully. Initially, weight bearing should be introduced with weight-shifting exercises in order to gradually promote co-contraction and muscle firing patterns that promote pelvic and hip stability. For instance, side-to-side leaning and forward and backward leaning in mini-lunge position, with the involved limb both forward and to the rear, allow the patient to experience variable static positions of gait in a closed kinetic chain. Progressive perturbation may be added during this exercise to promote increased neuromuscular recruitment (Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 5

(a and b) Mini-lunge weight bearing with perturbations provided by therapist. These exercises may be performed as weight-shifting exercises without intervention from the therapist or as a neuromuscular exercise where the therapist provides perturbations in arbitrary directions to promote stability and co-contraction of the trunk and lower limb. In either scenario, the patient attempts to maintain an upright position while weight shifting or reacting to the therapists perturbations

It is critical that weight-bearing activities are performed with optimal neuromuscular control. The absence of adequate muscle recruitment of the iliopsoas, gluteus medius, and gluteus maximus muscles in weight-bearing leads to increased anterior joint forces. Using three-dimension computer modeling, Lewis et al. [1] found that anterior hip joint force increased with increasing hip extension. Furthermore, decreased force contribution from the gluteal muscles during hip extension and the iliopsoas muscle during active hip flexion resulted in higher anterior hip joint force. This results in greater susceptibility to irritation of the surgical site and subsequent increases in pain and inflammation.

As patients strive to walk normally, a typical gait abnormality will develop. Between mid-stance and toe-off, anterior pelvic rotation increases while lumbar extension increases. Patients may increase lateral pelvic rotation in place of anterior rotation in the sagittal plane. This is typically due to inadequate, active hip extension. Oftentimes, passive hip extension will present normally and symmetrical compared to the uninvolved hip. However, when active hip extension is tested (see Table 2), it is often deficient. If left unaddressed, this gait abnormality may increase anterior hip pain and subsequently lead to secondary low back and sacroiliac joint pain. Therefore, a detailed progression of gait exercises, temporary gait modifications, and continuous verbal and tactile cuing is recommended.

Table 2

Quick test screen for progression to gait phase

Test | Procedure | Advancement |

|---|---|---|

Prone hip extension test | Patient is able to maintain proper gluteus maximus initiation and maintain activation beyond 0° hip extension | Patient can progress to weight-shifting exercises |

Single-leg balance test | Patient is able to maintain level pelvis without pelvic drop or rotation for 30 s | Patient can progress to unassisted short-distance indoor walkinga |

Once static double- and single-limb weight bearing are tolerated, gait may be introduced gradually and with caution. Devices such as an antigravity treadmill or walking in chest-deep water (see section “Aquatic Therapy”) allow patients to exercise normal, double-limb gait with less weight-bearing load on the hip joint. If these devices are not available, slowly progressing from TDWB to PWB to FWB while using two and then one crutch is advised. Additionally, patients are advised to begin walking slowly, with a shorter stride length to reduce anterior hip joint force [5]; this decreases the amount of hip extension required in the presence of insufficient gluteal contribution. Furthermore, using increased ankle push-off during gait can help to offset weakened gluteal musculature and decrease potential anterior hip joint force [17]. Soreness that resolves within 24 h is considered acceptable, yet patients that experience pain longer than 24 h are advised to discontinue weight bearing until the pain subsides and return to the previous level before progressing.

Simple cuing techniques can promote normal sequencing of muscle activation with movement. During hip extension, for example, Lewis et al. [18] discovered that cuing gluteal activation during prone hip extension caused simultaneous activation of the gluteal and hamstrings muscles rather than early activation of the hamstrings. During forward walking, cuing a patient to place emphasis on trunk control to limit anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar extension during mid-stance to toe-off will help to decrease this compensatory pattern and improve pelvic control. Slow backward walking with an emphasis on controlled, active hip extension from mid swing to toe contact may assist in recruiting the gluteal musculature during hip extension. Side stepping offers patients increased tolerance to weight bearing while eliminating sagittal plane movements of the hip, thus decreasing the potential for anterior hip pain.

Aquatic Therapy

Aquatic therapy is a valuable adjunct to a land-based physical therapy program . Water buoyancy in varying water depths offer patients decreased load on weight-bearing joint. Additionally, water offers a more stable environment for patients to perform activities that may otherwise be too difficult or painful to perform on land. Lastly, the warmth and pressure of water may help to decrease pain and swelling in the hip joint.

Patients may begin aqua jogging in deep water using a buoyancy suit and waterproof dressings as early as POD 3. Patients are progressed to chest-deep walking approximately 2–3 weeks after surgery. A similar progression of side stepping, forward walking, and backward walking is instructed as mentioned above. Furthermore, strengthening exercises can be performed in waist-deep water 2 weeks prior to land training. Pool running without a floatation device should begin 4 weeks prior to starting a land-based progression. When a patient can perform water running without pain, an interval progression may be implemented on dry land.

Criteria to Progress to Phase 3

Once gait is normalized and the proper exercise progressions of phase 2 have been mastered by the patient, it is appropriate to progress to initial strength and endurance of phase 3. Specific criteria that should be accomplished in phase 2 in order to ensure progression to phase 3 is appropriate include (1) normalized gait without pain or limping, (2) pain-free performance of phase 2 exercises absent of excessive compensatory patterns, (3) therapist discretion based upon clinical screening tools, and (4) ability to perform single-leg squat test for 1 min.

Phase 3

The ultimate goal of phase 3 of the rehabilitation program is to restore muscle strength, power, and endurance. Activities of daily living and recreational activities should become relatively asymptomatic during this phase. The physical therapist should continue to monitor compensatory patterns previously described during the progression from open kinetic chain to closed kinetic chain exercises and as the demand for range of motion, joint stability, and neuromuscular control increases. Careful consideration should be taken to determine the best exercise prescription based on the demands and functional goals of the patient while applying basic training principles of load, volume, frequency, and periodization when designing exercise prescriptions [19, 20]. Exercise specificity should be considered with athletes seeking to return to sports participation; however, this should not be overridden by fundamental physiologic, metabolic, and biomechanical voids that must be fulfilled prior to prescribing more complex and specific exercises.

Exercises should emphasize muscles that stabilize the hip joint and reduce anterior joint forces. These muscles include the GM, gluteus maximus, and Iliopsoas [1, 21]. Table 3 presents a series of exercise progressions for each of these muscle groups, which are based on empirical evidence [13–15, 22, 23], clinical rationale, and anecdotal expertise. However, therapists should exercise discrimination when prescribing these exercises based on the individual differences of each patient and clinical findings.

Table 3

Exercise progressions per muscle group

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree