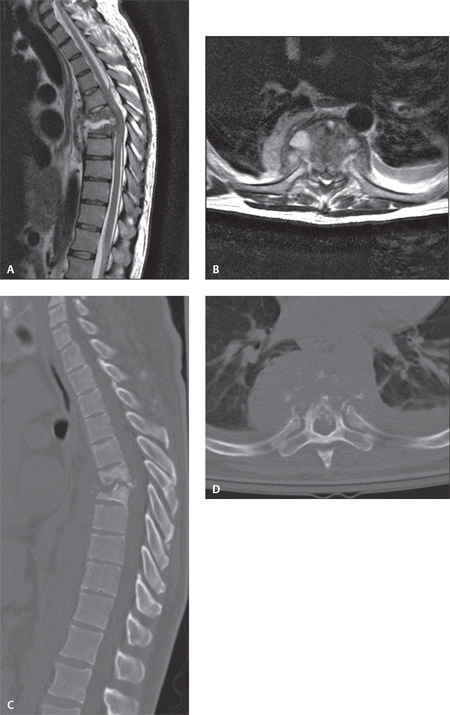

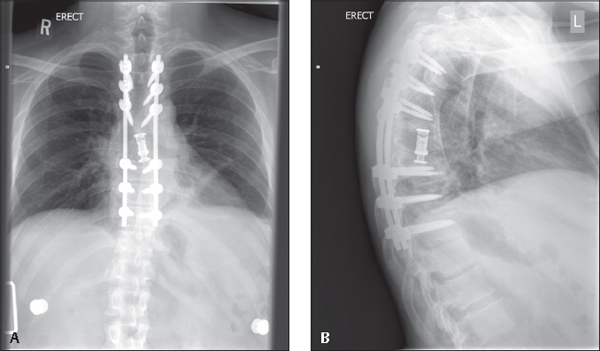

49 Purulent infections of the spinal column are relatively rare. Risk factors for a purulent spinal infection include diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, alcoholism, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), chronic steroid usage, the presence of an extraspinal infection, malignancy, prior surgery, and intravenous (IV) drug abuse. Most pyogenic infections are hematogenous in origin (i.e., spread to the spine via the vascular system). In some cases, direct extension of a local infection (e.g., empyema) can involve the spinal column. Purulent spinal infections are serious, with a mortality rate approaching 20% if not treated promptly and aggressively. The most frequent causative organisms include gram-positive aerobic cocci (80%), such as Staphylococcus aureus (60%), Streptococcus (10–20%), and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (10%). Gram-negative aerobic cocci are found in 15–20% of cases, including Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus species. A significant number of infections may be polymicrobial, especially in diabetic and immunosupressed patients or those with a history of IV drug abuse. Infections of the spinal column are most commonly classified on the basis of anatomical location. The most common locations for the infection include the vertebral bodies and disk space, facet joints, spinal canal, and perispinal soft tissues (e.g., psoas muscle). Infections of the spinal canal are often subclassified into epidural, subdural, and intramedullary, depending on the location of the abscess. Another related area of infection includes the sacroiliac joint. Patients with a pyogenic infection most commonly present with pain at the site of the infection and generalized symptoms, such as fevers, chills, or night sweats. The pain is often “nonmechanical” and is severe even at rest. Fever may not be present, depending on the location of the infection and the status of the patient’s immune system. Neurologic symptoms may be present for infections involving the spinal canal and may include anything from minor deficits to complete paralysis. Patients with spinal infections often appear grossly ill, but this is not always the case. Vital signs may show an elevated temperature. Patients with severe sepsis may exhibit findings of tachycardia and hypotension. There may be local tenderness around the site of the infection. A thorough neurologic examination is mandatory in cases where infection is suspected. The examination should be repeated frequently during treatment, as changes may occur. Serum laboratory studies, including white cell count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein level (CRP), are commonly ordered. Blood cultures are useful and may identify the organism in some patients. In patients with related medical conditions, such as diabetes or HIV, additional laboratory work may help to define the severity of the condition. Plain radiographs are often taken and may show destructive changes with chronic vertebral osteomyelitis; however, radiographic signs lag behind clinical ones, and radiographs may be negative for the first 3 weeks of a bony infection. Computed tomography (CT) is useful to visualize chronic destructive changes of the spinal column as well and may show an air/fluid level within the site of an abscess. However, in early spinal infections, plain radiographs and CT may be negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is thus the imaging modality of choice in most cases of pyogenic infection (Fig. 49.1). It is highly sensitive for spinal canal abscesses, diskitis, psoas abscess, and even early vertebral osteomyelitis. Gadolinium enhancement may be useful, especially in cases where the infection involves the spinal cord. MRI can be used to define the location and extent of the infection. Bone scans are helpful in cases of multifocal osteomyelitis and in subtle cases where the site of the infection is not evident. Gallium scanning has been described as useful in cases of chronic postsurgical infections in the setting of spinal hardware. Indium scanning is neither sensitive nor specific in the setting of spinal infections. Fig. 49.1 A patient with a significant spinal infection. Notice that there is evidence of bone and disk destruction and a large dorsal epidural abscess. (A,B) Sagittal and axial MRI. (C,D) Sagittal and axial CT scans. If no organism is identified on blood cultures, a biopsy sample of the infectious material should be obtained. Depending on the location and size of the infection, this may be done with fluoroscopic guidance, with CT guidance, or as an open surgical procedure. An adequate sample should include any abscess material and surrounding soft tissue from the focus of infection. The material should be evaluated with gram stain, aerobic, anaerobic, acid-fast, and fungal cultures. A biopsy for histology is also useful, as tumors may occasionally present with findings similar to infection. Nonsurgical treatment is indicated as the initial therapy for patients with infections involving the vertebral body, disk space, and perispinal tissues as long as there is no finding of significant involvement of the spinal canal and the neurologic examination is normal. After biopsy to identify the organism, treatment consists of targeted antimicrobial drugs and bracing/immobilization of the spinal column. Antimicrobial therapy generally involves intravenous dosing, which continues for at least 6 weeks. Serum laboratory test results including CRP level and ESR are followed during the course of treatment and should be returning to normal by the point that treatment is discontinued. Some authors have recommended oral antibiotics following the discontinuation of intravenous antibiotics. Patients with major immune dysfunction (e.g., patients with HIV or patients on chemotherapy for malignancy) are much more likely to fail nonsurgical treatment and, in some cases, are better served with early surgery. Patients with significant destruction of the spinal column leading to a kyphotic spinal deformity are also better served with surgical reconstruction. Surgical treatment involves an adequate débridement of the site of the infection, followed by reconstruction of any structurally significant bony defects. Rigid internal fixation is used to maintain stability at the site of the infection, and this facilitates resolution of the infection and bony fusion across the area (Fig. 49.2). Autogenous bone graft is preferred over allograft or other synthetic materials in the face of a serious pyogenic infection. When possible, the spinal instrumentation should be placed in a region of the spine that is not involved with the infection (e.g., posterior instrumentation following anterior débridement and grafting of diskitis/osteomyelitis. Postoperative antimicrobial therapy Fig. 49.2 (A,B) Postoperative images following reconstruction. The patient was treated with a decompressive laminectomy with evacuation of the epidural abscess followed by stabilization of the infected section using a pedicle screw and rod construct. The anterior column débridement and reconstruction were achieved from an extracavitary approach with resection of the infected bone in the vertebral bodies and reconstruction with an expandable titanium cage filled with autologous bone graft. Postoperatively, cultures grew out methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, which was treated with intravenous vancomycin for 6 weeks, resulting in resolution of the infection.

Pyogenic Infections of the Spine

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

History

Physical Examination

Special Diagnostic Tests

Laboratory Studies

Imaging Studies

Biopsy and Culture

![]() Treatment

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree