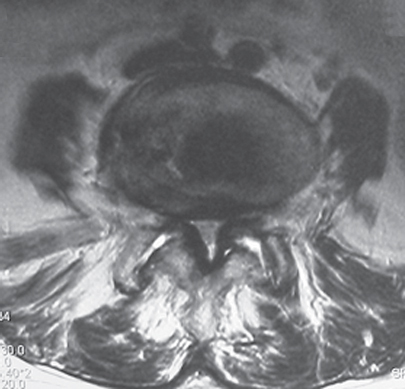

30 Lumbar spinal stenosis involves narrowing of the spinal canal and is a common condition among older adults with spondylosis. Some patients have congenitally smaller spinal canals, and this population is more likely to develop symptoms of stenosis as degenerative changes ensue. The anatomic sites of stenosis within the spine include the central canal, lateral recess (subarticular), and foramen, although a combination of regions is involved in many cases. Clinically, spinal stenosis may be asymptomatic or may involve disabling symptoms. The typical symptoms from spinal stenosis involve crampy buttock and/or leg pain, and subjective weakness with standing or walking. The symptoms are often relieved with spinal flexion or sitting. One third of patients will have unilateral pain more similar to classic radiculopathy. The causes of stenosis include congenital shortness of the lumbar pedicles, bulging intervertebral disks, infolding/thickening of the ligamentum flavum, and hypertrophy of the facet joints. Spinal canal stenosis is commonly associated with degenerative spondylolisthesis. The narrowing of the spinal canal leads to exclusion of cerebrospinal fluid in the stenotic regions of the spine, which limits the vascular and nutritional supply to the cauda equina. Because the spinal canal and neural foramen are narrowed when the spine is in an extended position, symptoms are generally at their worst with standing and walking. In addition to mechanical compression, vascular effects of stenosis include engorgement of the epidural venous plexus during ambulation, which worsens the compression dynamically. Stenosis patients classically present with symptoms of neurogenic claudication, causing crampy buttock and/or leg pain brought on by standing and walking. The symptoms may begin in the lumbar region, with more distal migration as the position of spinal extension is maintained. Many patients may also note heaviness or fatigue with prolonged walking, or lower extremity sensory disturbance. The symptoms are generally improved or relieved with sitting or spinal flexion (leaning on shopping cart). A subset of patients present with symptoms of unilateral radiculopathy, with radiating leg pain along a dermatomal distribution. The symptoms can generally be distinguished from vascular claudication, where the crampy leg pain is relieved by rest but not by spinal flexion. In addition to vascular claudication, other items in the differential diagnosis include peripheral neuropathy, nerve entrapment syndromes, hip and knee arthritis, or thromboembolic disease. A complete spinal, musculoskeletal, and neurologic examination should be a part of the patient’s evaluation, although the findings are often nonspecific. Some typical findings include a flattening of the lumbar lordosis, a slight forward lean during ambulation, and worsening of leg pain with maintained, standing hyperextension. It is rare to find major neurologic abnormalities or positive neural tension signs. It is important to evaluate the distal pulses to rule out vascular insufficiency, and to perform a detailed sensory examination to pick up findings of peripheral neuropathy. Additionally, a careful hip and knee examination should be performed to rule out evidence of symptomatic degenerative joint disease. Some have advocated the use of a “bicycle test,” in which the patient rides an exercise bicycle and then walks a fixed distance, with more tolerance of bicycling than of walking. Standard imaging studies include plain films and an advanced imaging study: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT)/myelography. The advanced imaging study (typically MRI) will demonstrate narrowing of the spinal canal due to a combination of facet hypertrophy, ligamentum flavum thickening, and annular bulging, causing compression of the neural elements. The axial images can be used to show the dimensions of the spinal canal (Fig. 30.1), whereas the parasagittal images are excellent for visualizing the intervertebral foramen. Additionally, MRI can be used to identify associated pathology, such as disk herniations or synovial cyst formation. A subset of patients will also be recognized to have coexistent degenerative spondylolisthesis. It is important to remember that there is a high occurrence of asymptomatic patients with imaging evidence of spinal canal stenosis and that treatment of asymptomatic stenosis is not currently indicated. CT myelograms can be used for patients who are unable to undergo MRI (Fig. 30.2A,B). Fig. 30.1 Axial CT demonstrating spinal stenosis.

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

![]() Pathoanatomy

Pathoanatomy

![]() Workup

Workup

History

Physical Examination

Spinal Imaging

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree