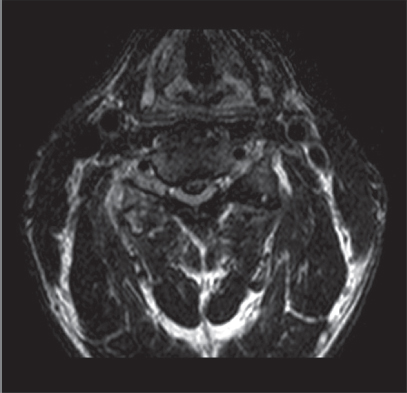

17 Cervical disk degeneration is commonly a matter of gradual, age-related deterioration of the intervertebral disks, but the condition is also affected by lifestyle, genetics, cigarette smoking, nutrition, and physical activity. Some people with disk degeneration develop symptoms, while others who also have disk degeneration remain asymptomatic. The reason for these differences is unclear. Most symptomatic disk degeneration occurs at the C5–C6 and C6–C7 levels, followed by the C4–C5 level. Two general types of symptoms are seen: axial neck pain, often due to disk degeneration itself, and neurologic symptoms due to a disk herniation resulting in compression of the nerve roots or the spinal cord. The normal aging process begins with disk desiccation, resulting in a decrease in the water content of the nucleus pulposus and weakening of the annulus fibrosus. With desiccation, the disk loses height and may bulge or permit the extrusion of nuclear material into the spinal canal or neural foramen, leading to compression of the neural structures. As the degenerative process progresses in conjunction with the more global process of cervical spondylosis, osteophytes develop along the posterior aspects of the uncovertebral joint, facet joint, and vertebral body. As the segment collapses, the ligamentum flavum can buckle inward, compromising the space available for the neural elements. Cervical disk disease has been categorized by Odom et al. into four groups: (1) unilateral soft disk protrusion with nerve root compression, (2) foraminal spur or hard disk formation with nerve root compression, (3) central soft disk protrusion with spinal cord compression, and (4) transverse ridging from cervical spondylosis with spinal cord compression. Cervical disk disease may present with general nonspecific symptoms, including axial neck pain, stiffness, loss of motion, and shoulder girdle pain. Posterior neck pain, worse with head extension and rotation, suggests a discogenic or facetogenic component, and posterior neck muscle pain, worse with head flexion, suggests a more common myofascial etiology. Neurologic symptoms may include radiculopathy or, less commonly, myelopathy. Radiculopathy presents as radiating pain into the arm(s), numbness, motor weakness, and posterior shoulder pain. Myelopathy presents with symptoms of arm and leg dysfunction, including weakness, numbness, and clumsiness in the hands, walking difficulties, and frequent falls. Patients with discogenic neck pain without nerve root involvement demonstrate a normal neurologic examination, decreased cervical range of motion, pain exacerbation with axial compression, and pain alleviation with neck distraction. Myofascial tenderness or trigger points, which may be primary in origin or secondary to other pathologic processes, are commonly palpable. Physical examination of the patient with radiculopathy may reveal weakness or decreased sensation along the affected dermatome. A Spurling test is often positive (increased radicular symptoms with neck rotation, lateral bending toward the affected side, and extension). Common physical findings due to myelopathy include hyperreflexia, spasticity, clonus, and pathologic reflexes (Hoffmann sign and Babinski reflexes). Because of a high rate of asymptomatic changes present on radiologic studies, any radiologic findings that reveal degenerative changes must be correlated with the patient’s symptoms. Initial evaluation should include plain radiographs, which may show disk space narrowing, osteophyte formation, possible metastatic disease, spinal deformity, and spine instability. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the standard diagnostic test for evaluation of the spine because of its excellent resolution in differentiating soft tissue, such as disk, ligament, and neural elements (Fig. 17.1). However, MRI is less adequate in visualizing the neural foramen and in assessing hard disk pathology or ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligment (OPLL). In these cases, myelography followed by computed tomography (CT) scanning is useful. Electrodiagnostic studies and nerve root blocks may play a role in evaluating or localizing neurologic lesions. Provocative cervical diskography has been controversial but may identify a symptomatic disk, assisting in evaluation of patients with inconclusive diagnostic tests and presurgical fusion planning. Fig. 17.1 Axial MRI T2 view of the C4–5 level showing the flattening of the spinal cord and myelomalacia secondary to cervical disk degeneration and herniation.

Cervical Disk Degeneration

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

History

Physical Examination

Spinal Imaging

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree