18

Psychological and Substance Abuse Disorders

At the completion of this chapter the reader should be able to do the following:

1. Recognize emotional and behavioral signs of common substance abuse and psychological problems, including mood, anxiety, eating, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders

2. Intervene appropriately with the affected athlete through discussion, supportive confrontation, education, and referral

3. Be aware of and establish collaborative relationships with qualified physical and mental health professionals in the recognition and treatment process

4. Identify a variety of educational and supportive resources (printed, web based, and organizational materials) that are available to both professionals and patients affected by these disorders

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies mental and behavioral health conditions as 4 of the 10 leading causes of disability worldwide and as affecting 25% of all people at some time in their lives.1 These four causes of disability are depression, anxiety disorders, suicide, and alcohol use. Other serious disorders include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, dementia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and panic disorder. Problems with attention and concentration, disordered eating, personality issues, and other forms of substance abuse also contribute greatly to the disease burden throughout the world.2 Some of these difficulties, chiefly depression, anxiety, and substance abuse problems, are ubiquitous in American society. The others, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), personality disorders, and disordered eating, are not as common. All can impair athletic performance and overall life adjustment. These conditions also can be difficult to treat, especially if allowed to escalate out of control. Therefore athletic trainers working with physically active people must be able to identify these potentially serious problems as early as possible. Following a description of typical physical and emotional symptoms, diagnostic criteria, and potential red flags, suggestions are made for initial intervention, referral, and treatment recommendations. The diagnostic criteria are taken from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV).3

Understanding the Role of Mental Health Professionals

The U.S. federal government has designated five disciplines with competency to provide mental health services to the population: (1) psychiatry, (2) psychology, (3) marriage and family therapy, (4) social work, and (5) psychiatric nursing (Table 18-1). Other professionals who provide mental health services include professional counselors and clergy members. Licensure and certification for most of these professionals are becoming standardized within each discipline, and the boundaries are better delineated among disciplines. A fair amount of overlap remains, however, and providers in any of these categories can potentially help with any of the clinical problems this chapter addresses. Referrals may be guided somewhat by the discipline of the professional but more importantly by the person’s clinical specialty.

TABLE 18-1

Disciplines Providing Mental Health Services

| Discipline | Typical Credentials | Approach |

| Psychiatry | MD, DO | Medical approach, including medication |

| Psychology | MS, PhD, PsyD, EdD | Psychological testing and counseling, individual psychotherapy |

| Marriage and family therapy | MA, MS, PhD | Biopsychosocial assessment, family systems therapy |

| Social work | MSW | Holistic approach; social services |

| Psychiatric nursing | RN, APRN | Medical approach, including medication |

Overview of Mental Health Issues in the Athlete

Framework for Understanding Mental Health

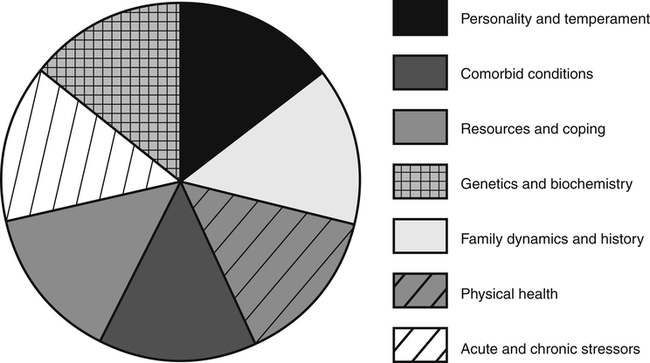

In virtually all situations a variety of overlapping factors are at play and contribute to symptom development. The biopsychosocial–spiritual model (BPSS) is a framework for understanding the individual’s responses in a given situation and development of symptoms. Symptom etiology may be conceptualized in terms of a pie metaphor. Figure 18-1 shows how these various factors overlap and contribute to overall well-being. In a given individual, the various pieces of the BPSS pie may be larger or smaller at any one time. The relative sizes of the pieces greatly influence the individual’s overall adaptation and symptom development.

Implications for Participation in Athletics

Early identification and treatment are very helpful in preventing problems from worsening, but sometimes the stigma still associated with mental health conditions prevents people from recognizing these problems in themselves or others. In that case, functioning in one or more areas of life can be affected, sometimes severely. Restricting an athlete’s participation in a sport if necessary will depend on the athlete, coach, and athletic trainer’s assessment of the individual’s level of functioning. The treatment plan, even when it includes appropriate medication, should not affect the athlete’s ability to participate. Initially, while the medication dose is being adjusted, the athlete could experience problematic adverse effects, such as nausea, headache, sedation, balance, or stimulation, that could affect participation or performance. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has no restrictions on the medications typically used to treat these conditions except for pemoline, a medication prescribed to treat ADHD.4

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is one of the most common human experiences. For example, most people have experienced a momentary sensation of “butterflies” in the stomach. In fact, the ability to respond with anxiety is considered normal and even desirable; and anxiety is what helps us “get our game face on” (Figure 18-2). However, given the right set of factors—physiology, central nervous system sensitivity, perceptual filters, belief system, coping, and support system—people may respond to one or more acute or chronic stressors by developing anxiety serious enough to be considered a disorder. This is a case of too much of a good or necessary thing. The individual is wracked with very serious and debilitating apprehension, excessive and ongoing worry, overwhelming fears, or compulsive behaviors. Some 40 million Americans (18.1% of the population) experience one of the more debilitating forms of anxiety and have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder.5

Red flags for problems with anxiety include outbursts of irritability or anger, substance abuse, changes in athletic performance, or other behaviors that are uncharacteristic for the athlete. Anxiety symptoms include both somatic–behavioral and emotional–cognitive disturbances.6 The presence of some or all of these symptoms may signal an anxiety problem or even an anxiety disorder (Box 18-1). People can be screened for anxiety disorders using a variety of standardized measures, such as the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a condition in which the individual is worried or nervous about many or most things in life. The person may complain on a regular basis of one or more of the anxiety symptoms listed previously. Box 18-2 summarizes criteria for diagnosing generalized anxiety. It has been estimated that 6.8 million people, or 2.7% of the American population, have this disorder. Women are twice as likely as men to report generalized anxiety.5 Consistent with the BPSS model described previously, the causes of GAD and other anxiety problems are varied. Fortunately, a number of effective treatment approaches and self-help measures are available.7

Panic Attacks

Among the 6 million people (2.7% of the population) who experience panic attacks, some say that these episodes seem to come out of nowhere when in fact they are probably in response to an accumulation of stressors. At other times the attacks may be stimulated by an identifiable, acutely stressful event.5 Symptoms that seem cardiovascular in nature are particularly striking during these episodes, for example, chest pain or shortness of breath. The attacks can be so overwhelming and produce such fear and intense anxiety that the affected person may begin avoiding stressful situations and other stimuli perceived as being triggers.8 As a result, the panic attacks may become panic disorder that can be accompanied by agoraphobia or avoiding going out into open spaces or public places. Panic disorder can be so severe and distressing that someone affected might consider suicide as the only way out; in fact, up to 20% of those affected consider this step. Women experience panic attacks at twice the rate of men.

Posttraumatic Stress Reactions

Similar to the intense responses involved in panic attacks are varying degrees of posttraumatic stress reactions (e.g., acute stress disorder [ASD], posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) experienced by approximately 7.7 million Americans.5 These reactions are in response to exposure to life-threatening events or other situations outside the normal range of human experience (e.g., war, serious physical or sexual assault, motor vehicle accident). ASD and PTSD result because the survivors have witnessed and/or experienced events that include serious injury, life-threatening trauma, or death. Examples of situations that have caused some of those involved to develop PTSD are the 9/11 attacks, the Iraqi and Afghani wars, and campus-based assaults and killings such as took place at Virginia Tech. People can be so overwhelmed by the event or series of events that they will go to great lengths to avoid similar situations, as well as the thoughts or feelings associated with the original experience, because their responses involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror.

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

Approximately 19 million individuals, or 8.7% of the U.S. population, display characteristics of anxiety in a more circumscribed manner by developing phobias to specific triggers or fears about specific issues. These include abnormal anxiety regarding being in social situations, public speaking, fear of flying, or preoccupations with germs or disease.5 These manifestations of anxiety can be less incapacitating if the person is successfully able to avoid the stimuli without compromising life and activities, but otherwise they can be quite disruptive. Some aspects of anxiety can be useful. For example, attention to detail and the ability to be thorough in a task can be very valuable attributes in environments such as athletic competition, where excellent performance is a premium. However, taken or driven to the extreme, these characteristics can be debilitating. Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a condition that affects approximately 2.2 million people in the United States and is equally common among men and women. The basis for OCD consists of persistent thoughts, impulses, or images about exaggerated or imaginary circumstances. The thoughts the person has are experienced as intrusive or inappropriate to the situation. Compulsive or repetitive behaviors are paired with the obsessions, with the goal of eliminating, reducing, or ignoring the resultant anxiety. As with the obsessions, the person frequently recognizes that the compulsive behaviors are, to some degree, excessive or unreasonable, especially if they impede the person’s performance, routine, or social activities. The most common obsessive thoughts are those concerning contamination, doubts, loss of order, horrible trauma, and sexuality. Table 18-2 summarizes common compulsive behaviors, and Box 18-3 lists diagnostic criteria for OCD.

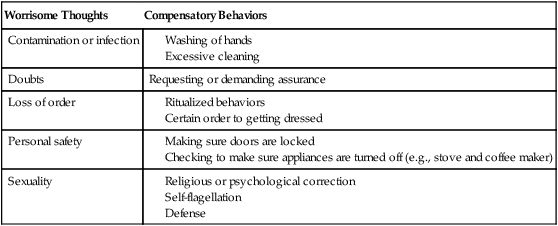

TABLE 18-2

Common Compulsive Thoughts and Behaviors Associated With Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

| Worrisome Thoughts | Compensatory Behaviors |

| Contamination or infection | |

| Doubts | Requesting or demanding assurance |

| Loss of order | |

| Personal safety | |

| Sexuality |