92 Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System

Outcome of PACNS is variable, with the highest rate of disability and mortality being seen in GACNS.

Epidemiology

Key Points

The incidence of PACNS is estimated at 2.4 cases per 1 million person-years.

PACNS occurs more commonly in men than women at a ratio of 2 : 1.

PACNS is a rare disease, first reported as a distinct clinical pathologic entity in 1959 by Cravioto and Feigin.1 The disease was initially described as “noninfectious granulomatous angiitis with a predilection for the nervous system” that is fatal. Other reports of similar clinicopathologic phenotypes emerged in the literature, and “granulomatous angiitis of the central nervous system” was proposed to describe this entity.2,3 Subsequently, different terms surfaced in the literature such as isolated angiitis of the CNS to encompass cases that were characterized by nongranulomatous pathologic findings.4 Currently, PACNS is a well-accepted terminology of this disease that emphasizes the sole involvement of the CNS.5,6 Following the description of diagnostic criteria for PACNS proposed by Calabrese and Mallek in 19885 and the potential for effective treatment,7 there was a tremendous increase of published cases in the literature such that more than 500 cases have now been described worldwide.8,9

Because of its rarity and our evolving understanding of PACNS, the true incidence of PACNS is difficult to calculate.9 In the recent era, the estimated annual incidence rate of PACNS is 2.4 cases per 1 million person-years.9 Middle-aged men are often affected by PACNS with a median age at onset of approximately 50 years with a male-to-female ratio of around 2 : 1.5,6,9

Clinical Features

Great progress has been made toward understanding the clinical features of PACNS despite the many challenges that include the lack of highly specific diagnostic modalities, the sparse material for research, and the lack of controlled clinical trials. In the recent era, specific clinical and pathologic subsets of PACNS that have prognostic implications have been identified.10–13

Proposed Criteria for Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System

In 1988 Calabrese and Mallek5 proposed diagnostic criteria for PACNS that emphasized the importance of ruling out mimics when diagnosing PACNS. These criteria include (1) the presence of an unexplained neurologic deficit after thorough clinical and laboratory evaluation; (2) documentation by cerebral angiography and/or tissue examination of an arteritic process within the central nervous system; and (3) no evidence of a systemic vasculitides or any other condition to which the angiographic or pathologic features could be secondary.

In 2009 Birnbaum and Hellmann12 proposed changes to the criteria described by Calabrese and colleagues, incorporating the levels of diagnostic certainty in their assessment. They proposed the term definite diagnosis of PACNS if there is confirmation of vasculitis on tissue biopsy and a probable diagnosis of PACNS when the diagnosis is based on high probability findings on an angiogram in the absence of tissue confirmation but with consideration of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) profiles and neurologic symptoms to discriminate between PACNS and its mimics.

Clinical Subsets

Initial attempts at subclassification of PACNS described three broad subsets: GACNS, benign angiopathy of the CNS (BACNS), and “atypical” PACNS.14 BACNS has since become recognized to be a part of the reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS)11 with the other PACNS subsets now being defined by pathologic or radiographic features.

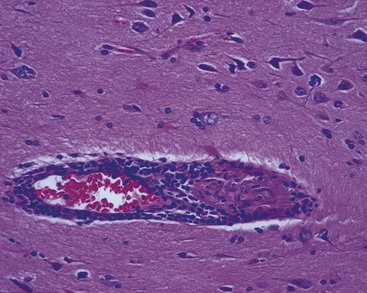

Granulomatous Angiitis of the Central Nervous System

GACNS is a subset of PACNS described as a clinicopathologic entity characterized by granulomatous angiitis confined to the brain. This is a rare subset of PACNS, in which patients clinically present with chronic insidious headaches along with diffuse and focal neurologic deficits. Because the disease is confined to the brain, meninges, or the spinal cord, signs and symptoms of systemic inflammatory diseases are usually lacking. The diagnosis of this subset is confirmed by the findings of granulomatous angiitis on pathology (Figure 92-1). Typically the CSF findings include those of an aseptic meningitis picture with negative staining for microorganisms. GACNS predominantly affects middle-aged men. The most common findings on neuroimaging include infarcts, most often bilateral, as well as high-intensity T2-weighted fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the subcortical white matter and deep gray matter. Cerebral angiogram is not the diagnostic modality of choice given its poor spatial resolution of detecting small vessel vasculitis, which mainly occurs in GACNS.

Atypical Central Nervous System Vasculitis

Masslike Presentation.

Masslike (ML) presentation is a rare manifestation of PACNS occurring in less than 5% of the cases. This presentation has gained attention after the recent report of a series of 38 patients with histologically confirmed PACNS that presented with a solitary cerebral mass.15 Typically the diagnosis is unanticipated and is confirmed after the pathologic examination from either biopsy samples or surgical excision of the mass. Unfortunately, there are no specific features on clinical assessment, neuroimaging, cerebral angiography, or CSF examination that could reliably distinguish ML-PACNS from other, more common causes of a solitary cerebral mass. Appropriate stains and cultures to rule out mycobacterial, fungal, or other infections and immunohistochemistry/gene rearrangement studies to exclude lymphoproliferative disease are essential to secure the diagnosis and exclude concomitant infectious or malignant processes.

Cerebral Amyloid Angiitis.

Amyloid protein, in particular amyloid-β peptide, a fragment of the amyloid precursor peptide, can deposit in the brain, causing disease ranging from Alzheimer’s disease to cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). CAA-related inflammation and angiocentric inflammatory reaction in CAA is referred to as amyloid-β–related angiitis (ABRA).16 Patients with ABRA tend to be older and more prone to hallucinations and mental status changes than other PACNS patients. MRI cannot distinguish between ABRA and other forms of PACNS, although there is a higher occurrence of cerebral hemorrhage in ABRA. ABRA carries a poor outcome, which could be related to older age and comorbidities.

Angiographically Defined Central Nervous System Vasculitis.

The poor specificity of the cerebral angiogram poses a major challenge in the diagnosis of PACNS. When the diagnosis of PACNS is based on angiographic findings, a thorough evaluation should be performed to rule out mimics, especially RCVS.17,18

Spinal Cord Presentation.

Spinal cord presentation of PACNS is a rare subset in which disease is present only in the spinal cord. The diagnosis is usually made by biopsy.19

Diagnosis and Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

CSF is an important tool in the evaluation of PACNS. Although CSF findings are nonspecific in PACNS, its value also lies in ruling out other entities. Obtaining appropriate CSF cultures, microbiologic stains, cytology, and flow cytometry are crucial in ruling infectious and neoplastic disease. Elevated protein, modest lymphocytic pleocytosis, and occasionally oligoclonal bands and elevated IgG synthesis characterize the CSF in 80% to 90% of patients with pathologically documented PACNS.5,20,21 The median CSF white blood cell count is around 20 cells/µL, and the median CSF protein is approximately 120 mg/dL.5,9

Radiologic Evaluation

MRI is a sensitive modality for the diagnosis of PACNS reaching 90% to 100%.9,22 Abnormalities include infarcts in 50% of patients, commonly affecting the cortex and the subcortex bilaterally.9,23 Affected areas include subcortical white matter, followed by deep gray matter, deep white matter, and the cerebral cortex.24 Hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted sequences are common but not specific for PACNS.25 Other abnormalities include mass lesions in 5% of patients15; leptomeningeal enhancement in 8% of the cases9; and gadolinium-enhanced intracranial lesions in about one-third of patients.9

Cerebral vasculature imaging by catheter-directed dye angiogram or through magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is an important modality in the diagnosis of PACNS. Alternating areas of dilatation and stenosis characterize the angiographic findings in PACNS and typically involve the vasculature on both sides but sometimes can involve single vessels.26 Other angiographic features include smooth tapering of one or multiple vessels. Although cerebral angiograms may visualize abnormalities in medium-sized vessels, they have limited sensitivity to detect abnormalities in small vessels that are less than 500 µm in diameter. Although cerebral angiography is valuable, its specificity for the diagnosis of PACNS can be as low as 25%.27 The reported “typical” angiographic findings for vasculitis are not specific to PACNS and can be encountered in atherosclerosis, radiation vasculopathy, or vascular spasm.26,27 Moreover, cerebral angiogram carries a poor positive predictive value in the diagnosis of PACNS in that the angiographic findings seen in RCVS can be consistent with those found in PACNS.28 Vascular studies should therefore be interpreted with caution and should not be considered the diagnostic “gold standard” in PACNS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree