5.3 Pregnancy and childbirth

Chapter 5.3a The physiology of pregnancy and childbirth

Introduction

Section 5.2 was dedicated to the roles of the reproductive system of both the male and the female, including the production of gametes, and the provision of an environment in which these gametes can meet to produce a zygote. This chapter explores what happens following the time of conception, which is when the gametes meet, and follows the stages of development of the embryo and fetus, together with the physiological changes that occur in the mother at this time. The chapter concludes with a description of the physiology of childbirth and of the puerperium, which is the 6-week period that follows childbirth, during which time the mother’s body begins to return to its pre-pregnant state.

The formation of the embryo

Conception

Out of the millions of spermatozoa that are ejaculated, only a few hundred reach the fallopian tubes. When these spermatozoa reach the ovum, only one will be permitted to penetrate the cell membrane of the ovum. As soon as penetration has occurred, there is a change in the cell membrane that prevents the remaining spermatozoa from attaching (Figure 5.3a-I). The nuclei of the male and female gametes contain only 23 single chromosomes, rather than 23 pairs. After fusion of the ovum and sperm, their nuclei fuse to form 23 pairs of chromosomes, giving a combination of genes which is totally unique to that zygote. Within a few hours this new nucleus divides, and the zygote begins to form into the ball of cells known as the embryo.

Development of the embryo after implantation

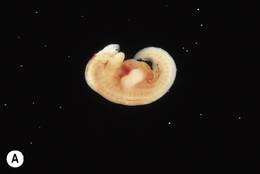

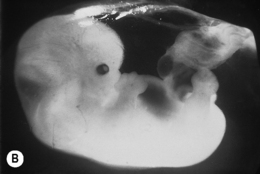

Another portion of the hollow ball of embryonic cells is destined to become the embryo itself. This portion develops within the fluid-filled cavity. By 2 weeks there is a definite lengthening of this mass of cells, so forming the primitive spinal cord. By 3 weeks a primitive heart has formed, with vessels connecting to those of the placenta. By 4 weeks a tube has formed from top to bottom, which will later develop into the gastrointestinal system, and by 6 weeks the first features of the kidneys and sex organs have appeared. By 7 weeks all the important organs have appeared. By this time there is a distinct form to the head, with bumps for the nose and ears, and also to the limbs, with tiny buds for the fingers and toes (Figure 5.3a-II).

Development of the fetus to the time of delivery

The fetal immune system

The progression of all the changes that occur in the fetus during its development are summarised in Table 5.3a-I (see Q5.3a-3) .

.

Table 5.3a-I The stages in the development of the fetus

| Age of gestation | Length of fetus | Stage of development of fetus |

|---|---|---|

| 14 weeks | 6 cm | |

| 15–22 weeks | 16 cm | |

| 23–30 weeks | 24 cm | |

| 31–40 weeks |

The physiological changes of pregnancy

The physiology of childbirth

The transition between the first and second stages of labour

It is usually around the time of transition that the waters break if they have not done so already.

Psychological changes in the puerperium

Chapter 5.3b Routine care and investigation in pregnancy and childbirth

At the end of this chapter you will:

Estimated time for chapter: 90 minutes.

Self-test 5.3a The physiology of pregnancy and childbirth

Self-test 5.3a The physiology of pregnancy and childbirth

1. In light of your understanding about the conventional medicine understanding of the requirements for a healthy conception, what sort of advice would you give to a couple who are planning to start trying for a baby?

2. What are the broad effects in pregnancy of:

3. From a conventional medicine perspective, what are the main health issues that predominate in the puerperium?

Answers

1. Your advice might cover the following topics:

Additional advice from the Chinese medicine perspective might focus on the adverse effect of a range of internal, external and miscellaneous causes of disease. Topics such as the specific content of a nourishing diet, moderate exercise, avoidance of climatic extremes and calm emotions might be discussed.

3. The important health issues to predominate in the puerperium include:

Routine antenatal care

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

.

.

.

.

Information Box 5.3a-I

Information Box 5.3a-I Information Box 5.3a-II

Information Box 5.3a-II Information Box 5.3a-III

Information Box 5.3a-III .

. .

.