Fig. 1

Possible diagnoses by layer

Table 1

Example of a hip layered diagnosis

Layer 1 | Femoral head cam deformity |

Layer 2 | Capsular laxity and labral tear |

Layer 3 | Gluteus medius tear |

Layer 4 | Deep gluteal syndrome/sciatic nerve entrapment |

Layer 5 | Lumbar spine arthrodesis |

History

Prior to the physical examination of the hip, a comprehensive history of the patient is obtained. Age and the presence or absence of trauma are the primary factors directing the examination. Documentation includes the chief complaint, the date of onset, and mechanism of injury. Detail the description of pain according to location, severity, and factors that increase or decrease the pain. Referred pain to the knee or lumbar spine often accompanies hip pathology and should also be investigated.

In addition to the standard history, the patients past medical and lifestyle history is acquired. Treatment to date must be clearly defined, including all conservative and surgical therapies. Hip preservation surgery is becoming more common; therefore, detailed prior surgical treatment is necessary for any revision surgery consideration. The patient’s functional status is assessed and current limitations are detailed, which may involve getting in or out of a bathtub or car, activities of daily living, jogging, walking, and/or climbing stairs. Related symptoms of the spine, abdomen, and lower extremity must be identified. Limitation of hip motion can lead to secondary problems in lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint, and pubic-inguinal musculotendinous structures [4–7], representing the fifth layer or kinematic chain. Knee ligament injury can also be associated to restrict hip mobility [8]. The presence of back pain and coughing or sneezing exacerbation help rule out thoracolumbar problems. Abdominal pain, anorectal and genitourinary complaints, and menses-related symptoms indicate intrapelvic or abdominal pathologies, which may coexist with hip problems. In addition, night pain, sitting pain, weakness, numbness, or paresthesia in the lower extremity may suggest neural compression, which can be located at the lumbar spine, inside the pelvis or within the subgluteal space. The following items must additionally be addressed: past injuries, childhood or adolescent hip disease, ipsilateral knee disease, suggestive history of inflammatory arthritis, and risk factors for osteonecrosis.

Hip pain often stems from some type of sports-related injury, mainly with rotational sports, such as golf, tennis, ballet, and martial arts. Five to six percent of adult sports injuries originate in the hip and pelvis [9]. Athletes participating in rugby and martial arts have also been reported to have an increased incidence of degenerative hip disease [10]. Documentation of sports activities can help determine the type of injury and guide the treatment considering the patient’s goals and expectations. A complete review of the history is given in Table 2.

Table 2

Complete review of patient history

A questionnaire is utilized in order to score the patient’s hip status. There are several questionnaires validated for the assessment of patient hip joint function and related pain. The Harris Hip Score (HHS) is the most documented hip score and was first described to evaluate patients with mold arthroplasty [11] and has been modified for more current use in hip arthroscopy [12]. As the hip joint questionnaires have evolved, the functional assessment has become more important, and self-administered questionnaires are preferred rather than observer administered [13]. The MAHORN (Multicenter Arthroscopy of the Hip Outcomes Research Network) Group has validated the International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33) [14]. Developed through an international multicenter study, the iHOT-33 is a self-administered questionnaire, and its target population is active adult patients with hip pathology. While the iHOT-33 was developed for research purposes, a short form (iHOT-12) [15] was also described for use in routine clinical practice. The Short Form 36 (SF-36) [16] and 12 (SF-12) [17] are questionnaires used for general health survey and are sometimes associated with the more hip-specific evaluation tools. Final outcome is dependent upon the effects of treatment which should consider the mental and spiritual aspects of the patient. This assessment has proven useful in heart and cancer treatment and is required in complex hip pathology evaluation due to the critical role the hip plays in all activities of daily life.

The diagnostic and treatment tools for adult and adolescent hip disorders have improved over the past decade. Choosing the best approach for each patient depends mainly on the patient expectations and goals. The history of complaint is important not only to define the diagnosis but also to choose the most appropriate option for each patient among the treatment alternatives [18]. The use of a common language and standardized history and physical examination will aid in the understanding of patients with complex pathology.

The Physical Examination of the Hip

The 21-step physical examination of the hip (Table 3) is a comprehensive assessment of four distinct layers: osteochondral, capsulolabral, musculotendinous, and neurovascular. A consistent hip examination is performed quickly and efficiently to find the comorbidities that coexist with complex hip pathology by assessing the hip, back, abdominal, neurovascular, and neurologic systems. Loose-fitting clothing about the waist is helpful for exposure and patient comfort. Documentation of the exam by an assistant on a standardized written form aids in accuracy and thoroughness. The use of a common language and specific technique for each examination test will eliminate multi-clinical discrepancy and improve reliability. The MAHORN (Multicenter Arthroscopy of the Hip Outcomes Research Network) Group outlined the common tests that form the basis of a multilayered hip evaluation [19]. This battery of tests covers all five layers of the hip.

Table 3

Twenty-one (21)-step physical examination of the hip

Standing | 1. Gait | Pelvic tilt/rotation, stride length, stance phase, FPA |

2. Single-leg stance phase test | Neural loop/abductor strength | |

3. Inspection | Leg lengths, forward bend/spine, body habitus, global laxity | |

Seated | 4. Neurovascular/reflex | Skin, lymphedema, sensory, DTR |

5. ROM | Internal and external rotation | |

Supine | 6. Palpation | Abdomen, adductor tubercle |

7. ROM | Abduction, adduction, flexion | |

8. Hip flexor contracture test | Psoas/hip flexor contracture | |

9. DIRI | FAI | |

10. DEXRIT | FAI, anteroinferior instability, apprehension | |

11. FADDIR | FAI | |

12. FABER | Hip vs. SI | |

13. Dial test | Laxity/instability | |

Lateral | 14. Palpation | GT facets and bursae, glutei origin/insertion |

15. Strength | Abduction, gluteus medius, gluteus maximus | |

16. Passive adduction tests | Tensor fascia lata, gluteus medius, gluteus maximus | |

17. Lateral rim impingement test | FAI, laxity, apprehension | |

18. Posterior rim impingement test | FAI, apprehension, contrecoup | |

19. Apprehension test | Laxity, contrecoup | |

Prone | 20. Rectus femoris contracture test | Rectus femoris contracture |

21. Femoral version test | Femoral anteversion |

Standing Examination

A general location of pain is noted by the patient pointing with one finger will usually help direct the examination. The groin region may be indicative of an intra-articular problem. Lateral-based pain may be associated with intra- or extra-articular aspects. A characteristic sign of patients with intra-articular hip pain is the “C Sign” [23]. The patient will hold his or her hand in the shape of a C and place it above the greater trochanter, with the thumb positioned posterior to the trochanter and fingers extending into the groin. Posterior-superior pain requires the differentiation of hip and back pain. Bilateral shoulder and iliac crest heights in the standing position are compared to evaluate leg-length discrepancies (Fig. 2a, b). Incremental heel lifts placed under the short side foot will help with orthotic considerations. Trunk bending (side to side and forward) is performed to evaluate the lumbar spine and to differentiate structural from nonstructural scoliosis (Fig. 2c, d). General body habitus and joint laxity are easily assessed in the standing examination (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2

Standing evaluation. (a) and (b). Shoulder and iliac crest heights are examined with the patient with dynamic loading of the hip joint in the standing position. (c). Spinal alignment is assessed during a forward bending of the trunk, palpating spinal alignment and noting the degrees of trunk maximal flexion. (d). Tests for generalized joint laxity of the elbows. (e). Passive opposition of the thumb to the flexor aspect of the forearm

Gait abnormalities often help detect hip pathology and the kinematic chain. The patient is taken to an area large enough to observe a full gait of six to eight stride lengths (Fig. 3). The key elements of gait evaluation include foot progression angle (FPA), pelvic rotation, stance phase, and stride length. The whole limb, including osseous and soft tissues, must be considered when evaluating any FPA abnormality. Increased femoral version can cause an internally rotated FPA, but it may be balanced by tibial lateral torsion or deficient medial hip rotators. The knee and thigh are observed simultaneously to assess any rotatory parameters. The knee may want to be held in internal or external rotation to allow proper patellofemoral joint alignment but may produce a secondary abnormal hip rotation. This abnormal motion is usually present in cases of severe increased femoral anteversion, precipitating a battle between the hip and knee for a comfortable position, which will affect the gait. The following abnormal gait patterns can be associated with hip pathologies: winking gait with excessive pelvic rotation in the axial plane, abductor deficient gait (Trendelenburg gait or abductor lurch), antalgic gait with a shortened stance phase on the painful side, and short leg gait with dropping of the shoulder in the direction of the short leg.

Fig. 3

Gait evaluation. A full gait of six to eight stride lengths is evaluated from behind (a) and from the front (b) as the patient walks in the hallway. Fundamental points of gait evaluation include foot progression angle, pelvic rotation, stance phase, stride length, and arms swing

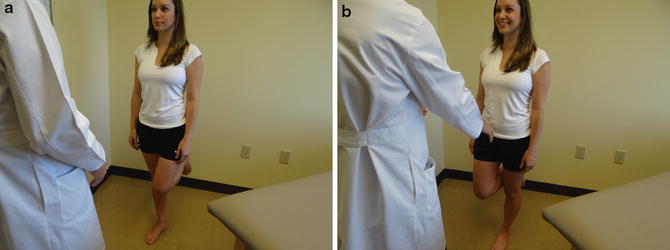

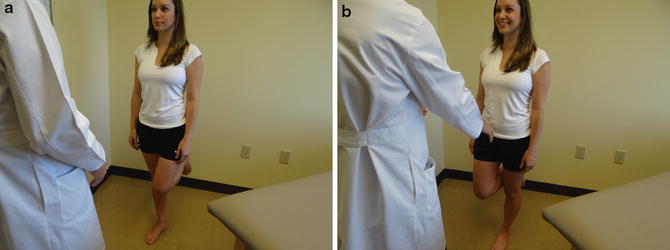

The single-leg stance phase test (Trendelenburg test) is performed during the standing evaluation of the hip. The single-leg stance phase test is performed bilaterally, with the non-affected leg examined first, to establish a baseline (Fig. 4). A positive is noted if the pelvis drops toward the nonbearing side or shift of more than 2 cm toward the bearing (affected) side, which may indicate that the abductor musculature is weak or the neural loop of proprioception is disrupted on the bearing side. Trunk inclination for the bearing (affected) side is also noted in a positive single-leg stance test. This assessment is performed in a dynamic fashion by some examiners.

Fig. 4

Single-leg stance phase test. (a), right side. (b), left side. Bilateral assessment, observed from behind and in front of the patient. The patients hold this position for 6 s

Seated Examination

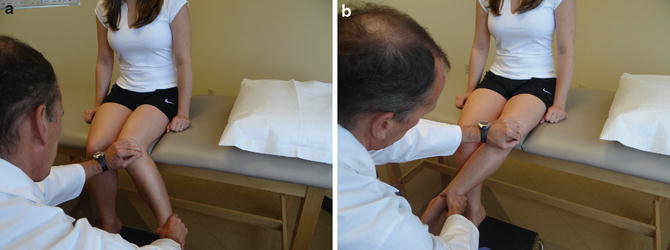

The seated hip examination consists of a thorough vascular, lymphatic, and neurologic examination, which are performed in all individuals (Fig. 5). Vascular and lymphatic assessment includes the posterior tibial pulse, any swelling of the extremity, and inspection of the skin. The neurologic evaluation includes sensibility, motor function, and deep tendon reflexes (patellar and Achilles). The presence of radicular neurologic symptoms is detected by the straight leg raise test, performed by passively extending the knee into full extension.

Fig. 5

Vascular, lymphatic, and neurologic examination. (a). Palpation of posterior tibial pulse and skin inspection. (b). Skin and lymphedema inspection. (c). Straight leg raise, useful in detecting radicular neurological symptoms

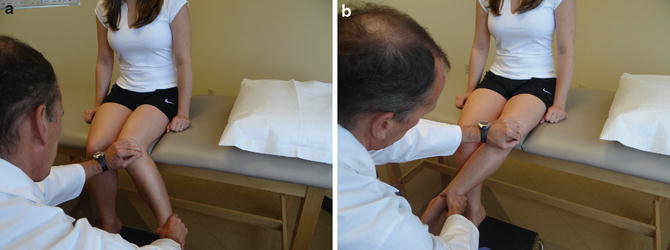

The seated position provides a reproducible and reliable platform for the assessment of hip internal and external rotation (Fig. 6). The ischium is square to the table at 90° of hip flexion. Values of hip rotation measured in different positions (seated, prone, supine) can be compared for an assessment of ligamentous versus osseous abnormality. Passive internal and external rotation is performed until a gentle endpoint is obtained and compared bilaterally. Proper hip function requires sufficient internal rotation, and there should be at least 10° of internal rotation at the midstance phase of normal gait [24], but less than 20° is abnormal. Excessive femoral anteversion may be indicated by increased internal rotation combined with a decreased external rotation. In contrast, excessive femoral retroversion may be indicated by increased external rotation with decreased internal rotation.

Fig. 6

Seated internal (a) and external (b) rotation range of motion. Passive internal and external rotation testing are compared from side to side. In the seated position, the ischium is square to the table, thus providing sufficient stability at 90° of hip flexion

Supine Examination

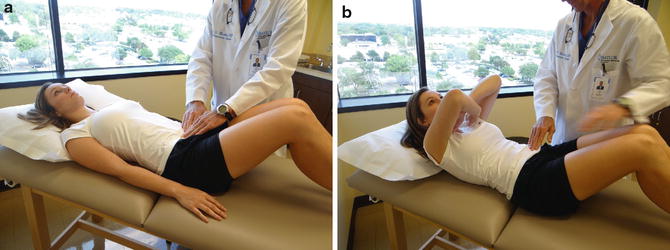

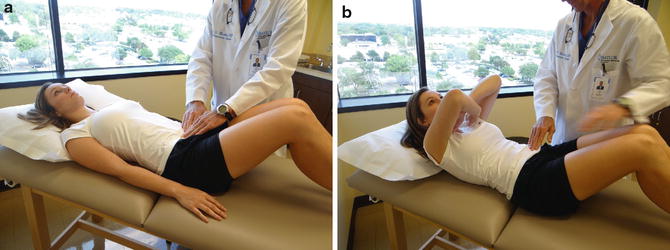

The supine examination begins with the inspection of leg-length discrepancy (Fig. 7). Tenderness with palpation is documented for the abdomen, pubic symphysis, and adductor tubercle. Differentiation of isolated adductor tendinitis and sports hernia may be made by a resisted sit-up torso flexion (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7

Supine assessment of leg lengths in a static position. Can be compared to the dynamic loading in the standing assessment

Fig. 8

Abdominal and pubic palpation. (a). Palpation in the relaxed supine position. (b). Palpation with abdominal contraction

Hip ranges of motion are recorded for passive abduction, adduction, and flexion (Fig. 9). Bring both of the patients’ legs into flexion (knees to chest) and note the pelvic position because the hip may stop early in flexion resulting in pelvic rotation to achieve end range of motion. With both legs in flexion, the pelvis is in a zero set point (eliminating lumbar lordosis) important for the hip flexion contracture test (Thomas test). The patient holds one knee to their chest and passively moves the contralateral leg into extension (Fig. 10). Inability for the back of the thigh to reach the table indicates the presence of contracture and patients with hyperlaxity or lumbar spine hyperlordosis can result in a false negative. In patients with hyperlaxity or connective tissue disorders, the zero set point can be established with an abdominal contraction.