Fig. 1

Three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction of left hip with prominent cam lesion as cause of femoroacetabular impingement. Note the loss of offset of typical anterosuperior location of femoral head-neck junction

A recent review of 113 patients who had symptomatic cam-type impingement demonstrated that bilateral cam-type deformity was present in 88 patients (77.9 %), while only 23 (26.1 %) patients demonstrated pain in both hips [13]. A higher alpha angle was associated with a significantly higher percentage of symptoms (69.9° vs. 63.1°, p < 0.001) [13]. Johnston et al. [14] recently evaluated the relationship between the size of the cam lesion and damage to the labrum and articular cartilage. In 82 patients who eventually underwent operative intervention, a higher alpha angle was associated with full-thickness cartilage delamination and greater detachment of the base of the labrum (Fig. 2).

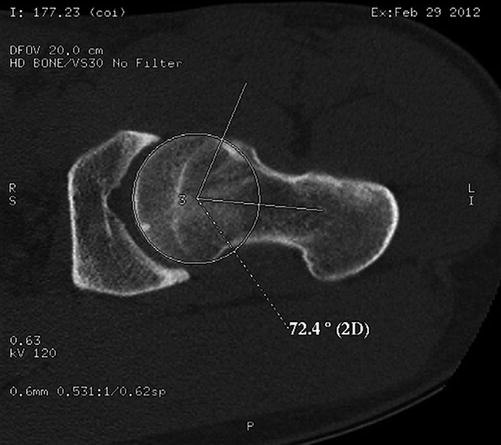

Fig. 2

Axial computed tomography image of patient with cam-type femoroacetabular impingement and abnormal alpha angle (72.4°)

The orthopedic surgeon can address cam lesions and the loss of head-neck offset with either arthroscopic or open approaches [15]. Mardones et al. [16] evaluated both open and arthroscopic femoral head-neck osteoplasty in a cadaveric model to determine any variations in efficacy of bony resection between the two approaches. The authors concluded that either method results in improved head-neck offset, although procedure time was significantly shorter in the open group. While depth and width of the osteoplasty were reliable with an arthroscopic approach, there was a tendency to underestimate the length of bony resection needed.

Acetabular Overcoverage

Focal Rim Impingement

Cephalad retroversion of the acetabulum , or a focal rim lesion, is another dynamic factor that is responsible for hip pain in the younger patient. The abnormal bone on the acetabular rim comes into contact with the normal femoral neck and results in tearing of the anterosuperior labrum. Focal rim lesions can be identified in anteroposterior (AP) radiographs as a crossover sign (Fig. 3). Other radiographic findings that may indicate impingement include the presence of os acetabuli or fractures of the acetabular rim, ossification of the labrum, and a pincer groove or trough sign laterally on the femoral head-neck junction. Patients with developmental dysplasia and Legg-Calve-Perthes disease may be more likely to have focal or global acetabular retroversion, or focal rim lesions [17].

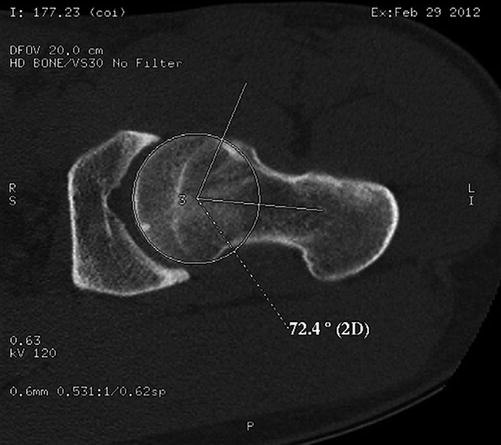

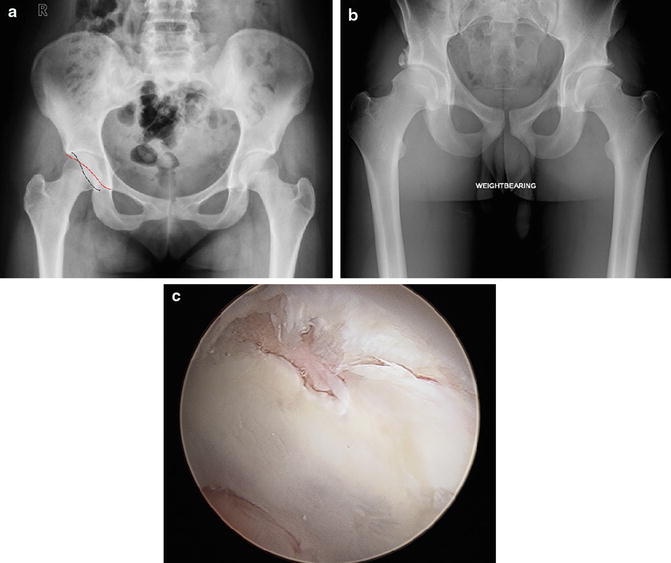

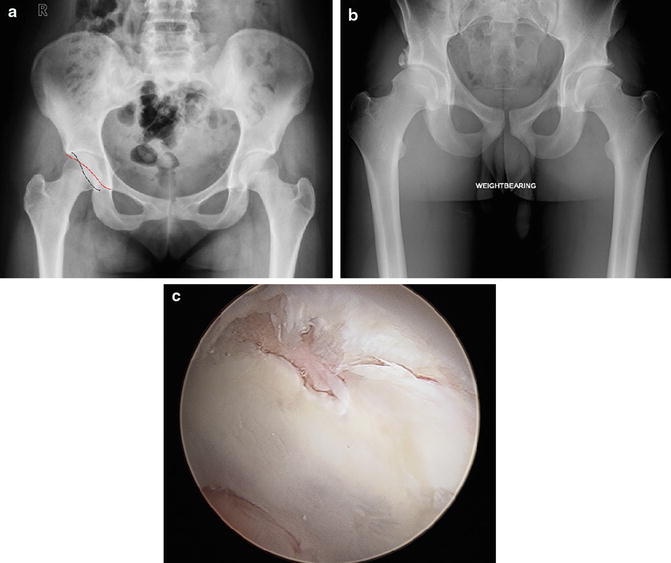

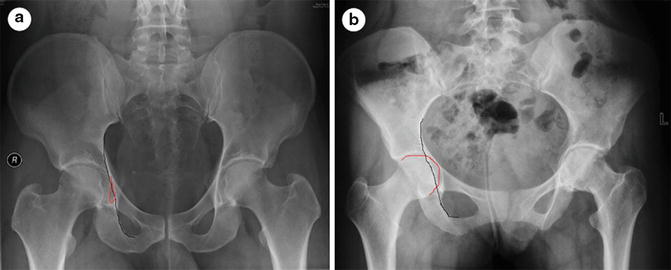

Fig. 3

(a) Anteroposterior (AP) pelvis radiograph demonstrating a crossover sign where a portion of the anterior acetabular wall lies lateral to the posterior wall causing “overcoverage” and impingement. (b) AP pelvis radiograph demonstrating right acetabular rim fracture in patient with pincer-type femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) . (c) Intraoperative view of patient with cam-type FAI as seen from the anterolateral portal demonstrating area of chondral injury at the chondrolabral junction. Such lesions are characteristic of cam lesions

Labral injury in these patients is often seen as intrasubstance fissuring and can be difficult to repair due to the poor tissue quality from repetitive impingement between the femoral head-neck and the acetabular rim. As the labral tissue undergoes degeneration, bony apposition increases between the femoral head and the anterosuperior acetabulum. Eventually, the labrum undergoes ossification and callus may form at sites of repetitive contact [7, 9]. Chronic impingement also creates a “contrecoup” pattern of cartilage loss within the posteroinferior edge of the acetabulum due to levering of the head on the overhanging acetabular rim with subsequent shearing of the acetabular cartilage [18, 19].

Byrd and Jones [20] have demonstrated good results with arthroscopic treatment of pincer-type lesions at 2-year follow-up. In their study of 100 patients, 79 % had good-to-excellent results with an overall median improvement in Harris Hip Scores (HHS) of 21.5 points. Zumstein et al. [21] performed a cadaveric study demonstrating that focal rim lesions located more posterosuperiorly are less accurately resected during hip arthroscopy performed through anterior or anterolateral portals due to difficulty in identifying the posterior starting point for resection.

The anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) prominence has recently been recognized as a cause of extra-articular impingement. Abnormal morphology of the AIIS is a form of focal rim impingement as extra bone formation around the insertion of the rectus femoris is a block to mechanical motion and can serve as a pain generator (Fig. 4). When this abnormal bone is identified as a source of impingement, surgical options in the form of arthroscopic resection exist. Hetsroni et al. [22] recently reported on a series of ten patients who underwent arthroscopic decompression of AIIS-type deformity. AIIS deformity is often not present in isolation, as anterior cam lesions may also be present and addressed at the time of surgery. In nine patients, an anterior cam lesion was also identified and decompressed. Postoperatively, terminal hip flexion improved from 99° to 117°, with an average improvement in modified HHS of 34 points (64–98) [22]. More recently, Hetsroni et al. [23] classified various types of AIIS (subspine) morphology depending on the extent of bony deformity based on computed tomography (CT) and dynamic software analysis. In type 1, the distal AIIS ends proximal to the acetabular rim. Type 2 subspine deformity is described in cases when the AIIS extends up to the acetabular rim, and type 3 subspine deformity extends beyond the acetabular rim. The AIIS can be successfully decompressed arthroscopically; however, the deformity must be clearly delineated preoperatively [23].

Fig. 4

(a) Three-dimensional computed tomography imaging demonstrating abnormal morphology of the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) , which is a cause of focal rim impingement due to extra bone formation around the insertion of the rectus femoris. (b) This bone is a clear block to mechanical motion, as demonstrated in this computer templating image whereby the anterior inferior neck impinges on the prominent AIIS and can serve as a pain generator, which is a very common finding in subspine impingement

Mixed Impingement

Mixed impingement consists of hips with both femoral and acetabular deformities, and it is the most common form of FAI [9, 18]. A large population-based prospective survey of 2,081 young adults (874 males and 1,207 females) demonstrated cam-type deformities in 868 and 1,192 male and female subjects, respectively, with 187 males (21.5 %) and 39 females (3.3 %) demonstrating a pistol grip deformity with focal femoral neck prominence [24]. Pincer deformities were also seen in this group of males and females. Examination of AP radiographs revealed 203 (23.4 %) posterior wall signs, and the crossover sign was seen in 446 males (51.4 %) and 542 females (45.5 %) [24]. It is thus important to recognize the coexistence of femoral and acetabular deformities, and that deformity is often present bilaterally even in patients with only one symptomatic hip. Nepple and colleagues noted similar findings in a retrospective review of football players with a history of groin pain or injury at the National Football League Combine [25]. Radiographic evidence of isolated cam-type deformity was present in only 12 hips (9.8 %), while isolated pincer-type FAI deformity was seen in 28 hips (22.8 %). There was, however, a high incidence of radiographic pincer- and cam-type FAI in this population (116 of 123 players, 94.3 % of hips). In another recent hospital-based study of asymptomatic patients, a review of radiographs of 522 hips showed a high prevalence of FAI, affecting over 90 % of the cohort. Signs of mixed-type FAI were seen in 82 hips, or 15.7 % of the patients evaluated [26]. Combined impingement lesions present with different patterns of cartilage and labral pathology, and thus it is important to correctly identify and treat all pathology at the time of surgical intervention. It is well reported that in cam-type impingement, the majority of damage to the labrum occurs anterosuperiorly, while in pincer impingement the damage to the labrum and underlying cartilage occurs more circumferentially, although the greatest damage occurs between 11 and 1 o’clock [7]. It is thus important to recognize the coexistence of femoral and acetabular deformities as this has implications for localization of cartilaginous and labral damage, which can be present bilaterally even in patients with only one symptomatic hip.

Global Acetabular Retroversion

Global retroversion of the acetabulum may present with very similar symptomatology to focal rim lesions; however, it represents an entirely different clinical problem of overcoverage anteriorly and undercoverage posteriorly [5]. This clinical entity can be recognized on the preoperative AP pelvis radiograph by the so-called posterior wall sign, whereby the outline of the posterior wall passes medial to the center of the femoral head [27]. Another radiographic sign, the ischial spine sign, also indicates acetabular retroversion and represents a prominent ischial spine as seen on the AP pelvis radiograph (Fig. 5) [28]. This combination of anterior overcoverage and posterior undercoverage can predispose these patients to posterior instability or dislocation. Surgical treatments that involve aggressive anterior rim decompression may put the patient at higher risk by creating global undercoverage with resultant instability. Although rare, symptomatic posterior instability can be addressed surgically with a reverse “anteverting” periacetabular osteotomy [7].

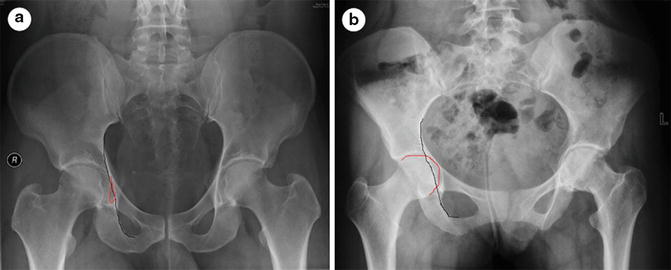

Fig. 5

Standard (anteroposterior) radiograph of patient with femoroacetabular impingement, demonstrating crossover sign and bilateral retroverted acetabula as evidenced by prominent ischial spines bilaterally (black outline)

Global Acetabular Overcoverage

Coxa profunda or protrusio deformities are characterized by a deeper-than-normal acetabulum. Radiographic evaluation of the normal hip on an AP pelvis radiograph demonstrates a teardrop that is lateral to the ilioischial line. However, in cases of coxa profunda and protrusio, the teardrop or femoral head touches or crosses medial to the ilioischial line, respectively (Fig. 6). As a result of the altered acetabular morphology, the medial joint space is more susceptible to osteoarthritis from altered load transmission patterns, whereas the superior joint space initially remains unaffected [29, 30]. Leunig et al. [29] recently described a number of important morphologic findings in patients with protrusio-related osteoarthritis of the hip. Compared to patients without protrusio deformity who develop hip osteoarthritis, those with protrusio demonstrate significantly decreased medial joint space with increased superior joint space. In addition, the ilioischial line was lateral to the acetabular fossa in patients with protrusio, and the neck-shaft angle was substantially lower in this group than in the osteoarthritis control group (121° vs. 130°). Lastly, a “contrecoup lesion” was identified as a significant cause of osteoarthritis in the posteroinferior joint in hips with protrusio deformity and was proposed to initiate the process of cartilage degeneration [29].

Fig. 6

(a) Anteroposterior pelvis radiograph showing deeper-than-normal acetabulum with medicalization of the teardrop (red outline) to the ilioischial line (black line). (b) Protrusio deformity results from additional medicalization of the femoral head (red outline) medial to the ilioischial line (black line)

Although global acetabular overcoverage can cause symptoms that are similar to focal rim lesions, the pattern of impingement is different and instead occurs circumferentially around the acetabular rim. Therefore, careful review of preoperative radiographs is necessary to recognize this pattern and allow the treating surgeon to understand that arthroscopic rim resection may address only a small portion of the mechanical zone of impingement. Some authors have recommended a surgical hip dislocation to address global overcoverage, whereas others have described variation of dual-portal arthroscopy to address the pincer impingement [29, 31]. In addition to performing an acetabular rim trim with labral refixation, some hips also require an osteochondroplasty of the head-neck junction to improve femoral head-neck offset and restore the normal concavity. Also, depending on articular cartilage damage present, a valgus intertrochanteric or pelvic-sided osteotomy may be indicated to shift the weight-bearing zone and prevent further degeneration of the articular cartilage [9, 32].

Femoral Retroversion

Retroversion of the femur has been described as a distinct dynamic factor that can cause mechanical hip pain in the young patient. In the adult male, the mean femoral anteversion angle measures approximately 15° [17]. Relative (<15°) or absolute (<0°) retroversion can increase functional external rotation while reducing the amount of hip internal rotation. Patients with both cam-type impingement and femoral retroversion will have pain earlier in the hip flexion arc of motion, as the retroverted femur rotates the cam lesion into the socket at lower angles of hip flexion. This places patients at higher risk for impingement symptoms during daily activities like sitting at a desk or getting in and out of a car [1, 5]. On the other hand, a patient with excessive femoral anteversion may not have symptoms of impingement until terminal hip flexion and have fewer painful restrictions in motion.

Surgical treatment consisting of cam decompression is usually successful in alleviating pain in patients with a loss of femoral head-neck offset and relative femoral retroversion. Kelly et al. [15] recently presented a series of patients with femoral retroversion who underwent arthroscopic decompression and had an overall improvement in hip range of motion, specifically internal rotation, after arthroscopic surgery. However, when a significant portion of the cam lesion is located more posterolaterally, open surgical dislocation is necessary to perform a complete resection and protect the retinacular vessels [7, 33]. If arthroscopic techniques are utilized for more posterolateral lesions, the hip should be placed in traction and extension to more safely visualize this area [34]. Isolated femoral retroversion, in the absence of concurrent cam or pincer lesions, can be treated with a femoral derotational osteotomy.

Extra-articular Impingement

Coxa Vara and Trochanteric-Pelvic Impingement

Coxa vara is another dynamic factor that must be recognized in the evaluation of mechanical hip pain and can be the result of multiple etiologies, including slipped femoral epiphysis, Perthes disease, trauma, or previous infection. It also may be caused by a developmental abnormality of the femur [35–37]. Femoral varus results in a relative shortening of the femoral neck and prominence of the greater trochanter as a result of a reduced neck-shaft angle. This can result in extra-articular lateral impingement of the greater trochanter on the AIIS (Fig. 7). Greater trochanteric impingement against the pelvis is classically seen in the setting of coxa vara and in individuals with a prominent greater trochanter [38]. The version of the femur is important to recognize when considering the diagnosis of greater trochanteric impingement. In the setting of femoral retroversion, patients have a functional decrease in internal rotation [1, 5], which can manifest itself as anterior trochanteric impingement with deeper degrees of flexion and internal rotation. Similarly, those patients with femoral anteversion have a functional increase in internal rotation and may manifest symptoms of posterior trochanteric impingement with external rotation. In cases of mild coxa vara, osteoplasty of the cam lesion and/or acetabular rim lesion is usually sufficient to resolve the impingement; however, in cases of significant varus deformity (<125°), a more extensive procedure such as relative femoral neck lengthening with a trochanteric osteotomy and distal trochanteric advancement may be required to address the severity of the mechanical impingement [32].

Fig. 7

Anteroposterior image of a right hip demonstrating coxa vara , which results in relative shortening of the femoral neck and prominence of the greater trochanter. This prominence leads to extra-articular lateral impingement of the greater trochanter on the anterior inferior iliac spine

Ischiofemoral Impingement

Ischiofemoral impingement is a less commonly described source of extra-articular impingement and is caused by impingement between the ischium and femur, often in the setting of previous operations or trauma [39, 40]. Radiographic imaging often demonstrates abnormality of the quadratus femoris muscle, which becomes injured as a result of impingement between the ischial tuberosity and lesser trochanter [39]. A recent cadaveric study evaluating quadratus femoris injury within the ischiofemoral space found that while degenerative changes were present within the majority the muscles analyzed, there was no association between injury and degeneration with the size of the ischiofemoral space [41]. These patients typically have pain with hip extension as well as pain that can radiate toward the knee and may be the result of prior myotendinous injuries at the ischial tuberosity from proximal hamstring injury [42, 43] (Fig. 8). Initial treatment should be focused on conservative measures, and surgical decompression at the level of the ischial tuberosity and lesser trochanter is reserved for cases where nonoperative measures fail to relieve pain [42, 44].

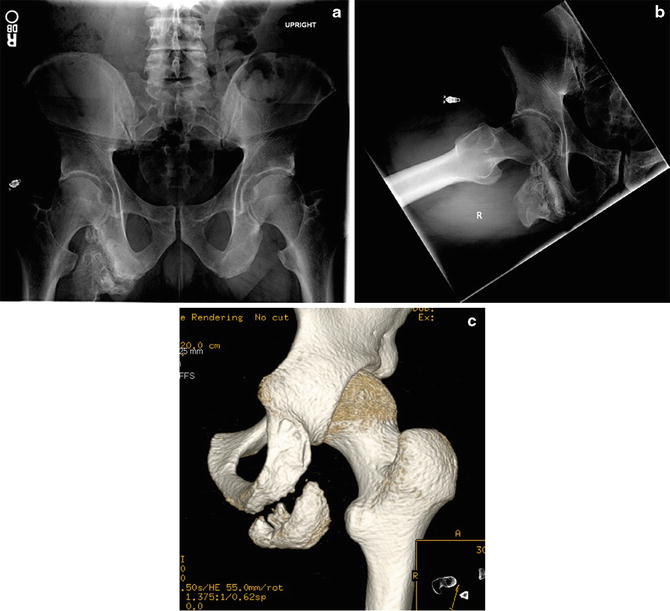

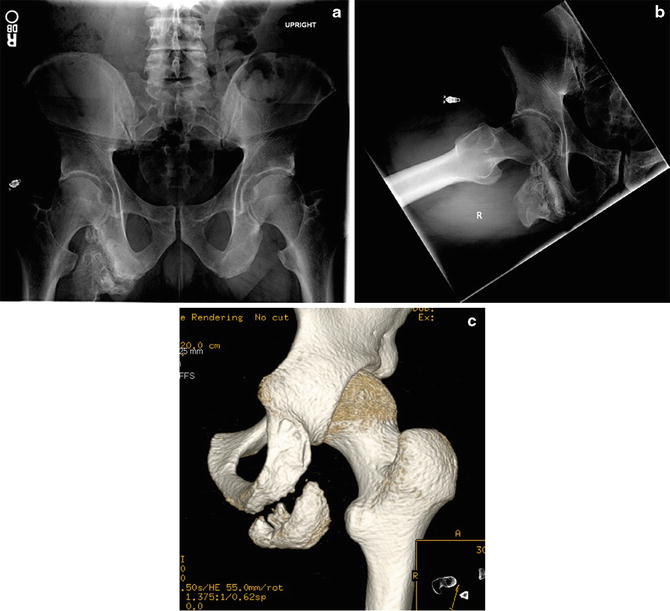

Fig. 8

Ischiofemoral impingement is commonly seen in the setting of previous surgery or trauma. (a) Anteroposterior pelvis radiograph demonstrating significantly diminished clearance between the ischium and proximal femur. (b) Lateral radiograph demonstrating significantly decreased space between posteroinferior proximal femur and the abnormal ischial bone, resulting in a significantly limited arc of motion and impingement. (c) Three-dimensional computed tomography image of previous bony avulsion injury of the ischial spine in a patient with ischiofemoral impingement

Static Factors

Acetabular Dysplasia

Hip dysplasia is a condition in which the hip joint develops incorrectly during early infancy and childhood, with eventual abnormal morphology of the acetabulum , femoral head , or both [45]. As a result, anterior or lateral undercoverage of the acetabulum can lead to elevated contact pressures toward the posterosuperior rim of the acetabulum (Fig. 9). This reduced contact area contributes to premature cartilage and labral degeneration and ultimately osteoarthritis [46–49]. Another complicating factor is that global undercoverage results in structural instability and allows the femoral head to migrate into regions of acetabular deficiency. These recurrent subluxation events can also lead to degeneration and chondral injury [50].